Right Ventricular Hypertrophy

- Article Author:

- Priyanka Bhattacharya

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Ellison

- Updated:

- 8/24/2020 10:49:42 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Right Ventricular Hypertrophy CME

- PubMed Link:

- Right Ventricular Hypertrophy

Introduction

Right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) is an abnormal enlargement or pathologic increase in muscle mass of the right ventricle in response to pressure overload, most commonly due to severe lung disease. The right ventricle is considerably smaller than the left ventricle and produces electrical forces that are largely obscured by those generated by the larger left ventricle.[1][2][3]

Size and function of the right ventricle are adversely affected by the following:

- Pulmonary hypertension with or without left ventricular dysfunction

- Conditions that affect the tricuspid valve leading to significant tricuspid regurgitation (TR)

Anatomy and Physiology

The right ventricle is composed of inflow (sinus) and outflow (conus) regions, separated by a muscular ridge, the crista supraventricularis. The inflow region includes the tricuspid valve (TV), the chordae/papillary muscles as well as the body of the RV. The RV body boundaries are formed by the RV free wall, extending from the interventricular septum's anterior and posterior aspects. The standard septal curvature convexes toward the RV cavity and imparts a crescent shape to the right ventricle when cross-sectioned. The RV's interior surface is heavily trabeculated; this feature along with the moderator band and more apical insertion of the TV-annulus impart key morphologic differences that distinguish the RV from the LV by echocardiography. In contrast, the infundibulum is a smooth, funnel-shaped outflow portion of the RV that ends at the pulmonic valve. Thus, the RV has a complex geometry, with traditional RV free-wall thickness of 0.3-0.5 cm, imparting greater distensibility and larger cavity volumes in the RV versus the LV, despite lower end-diastolic filling pressures. This translates to an RVEF that is typically 35% to 45% (versus 55% to 65% in the LV) yet generates the identical SV as the LV.

Changes in preload, afterload, and intrinsic contractility of the ventricle influence the systolic function of the RV, like the LV. Differences in RV muscle fiber orientation dictate that the body of the RV shortens symmetrically in the longitudinal and radial planes; thus, longitudinal shortening accounts for a much larger proportion of RV ejection than in the LV. The relatively conspicuous RV shortening along the longitudinal axis can measure RV systolic function using uncomplicated techniques that do not require geometric assumptions or meticulous endocardial definition, both being known limitations to the noninvasive assessment of RV systolic function.

Etiology

We will discuss right ventricular hypertrophy further with regards to the development of pulmonary hypertension or significant TR.[4][5][6][7]

The most common etiology of right ventricular hypertrophy is severe lung disease. The disorders that induce pulmonary hypertension and secondary right ventricular hypertrophy include the following (Table 1):

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

- Pulmonary hypertension owing to left heart disease

- Pulmonary hypertension from lung disease and/or hypoxia

- Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH)

- Pulmonary hypertension with unclear multifactorial mechanisms

Causes of primary TR include:

Direct valve injury secondary to cardiac instrumentation, chest trauma, Ebstein anomaly, rheumatic fever, infective and marantic endocarditis, right ventricular ischemia/infarction, tricuspid valve prolapse, connective tissue disorder, carcinoid syndrome and drug-induced TR.

Other less common causes of right ventricular hypertrophy are high altitude, left to right shunt, an atrial septal defect, a ventricular septal defect, anomalous pulmonary venous return, Eisenmenger syndrome, stenosis of the pulmonic valve or pulmonary artery, hyperthyroidism, cardiac fibrosis and cardiomyopathy affecting RV, and athlete heart syndrome.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology of right ventricular hypertrophy depends on the underlying cause. The epidemiology of PH varies among the 5 groups. Best studied is group 1 PAH; idiopathic and familial PAH, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 10 to 52 cases per million adults worldwide.

The exact prevalence of PH due to left heart failure is not well defined, in part because of variations in study design, PH definitions, and diagnostic modalities employed. Most echo-based series suggest that left heart disease causes 70% of PH.

Group 3 PH appears to be more prevalent in older adults. In one study of patients, 65 years and older with PH, group 3 PH occurred in 14%, while 28% had group 2 PH and 17% had mixed group two-thirds PH.

The true incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is unknown but estimated to be between 1% and 5% among survivors of acute pulmonary embolism.

Pathophysiology

The primary cause of significant pulmonary hypertension (PH) is almost always increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Increased flow alone (i.e., right ventricle output) does not usually cause significant PH because the pulmonary vascular bed vasodilates and recruits vessels in response to increased flow. Similarly, increased pulmonary venous pressure (represented by the alveolar occlusion pressure) alone does not usually cause significant PH. However, a chronic increase of either flow and/or pulmonary venous pressure can increase pulmonary vascular resistance. Numerous medical conditions can alter all variables:

- Increased PVR may be due to conditions associated with occlusive vasculopathy (remodeling and altered vascular tone) of the small pulmonary arteries and arterioles (conditions associated with PAH), conditions that induce hypoxic vasoconstriction (hypoventilation syndromes and parenchymal lung disease), or conditions that decrease the cross-sectional area of the pulmonary vascular bed (pulmonary emboli, interstitial lung disease).

- Increased flow through the pulmonary vasculature may be due to congenital heart defects with left-to-right shunt (atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus), anemia, or liver cirrhosis.

- Increased pulmonary venous pressure may be due to left ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction, mitral valve disease, constrictive or restrictive cardiomyopathy or pulmonary venous obstruction (eg, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease).

PAH is a proliferative vasculopathy of the small pulmonary muscular arterioles (less than 50 microns) that is often characterized by vasoconstriction, hyperplasia, hypertrophy, fibrosis, and thrombosis involving all three layers of the vascular wall (intima, media, and adventitia). Patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and heritable variants may have a genetic predisposition to PAH (bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 mutations) with additional contributing mechanisms including vasoactive mediators, potassium channel dysfunction, and abnormal response to estrogen. The pathogenesis of other forms of PAH such as drugs and toxins, connective tissue disease, congenital heart disease, human immunodeficiency virus, portopulmonary hypertension, schistosomiasis, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, or persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn is poorly understood.

TR is characterized by the backflow of blood into the right atrium during systole. Since the right atrium is relatively compliant, there are often no major hemodynamic consequences with mild or moderately severe TR. However, when TR is severe, right atrial and venous pressure rise and can result in the signs and symptoms of right-sided heart failure. In such patients, right ventricular pressure and/or volume overload frequently lead to right ventricular systolic dysfunction and a low forward cardiac output.

History and Physical

Symptoms

Symptoms due to pulmonary hypertension (either primary or secondary) and/or severe TR disease include the following:

- Exertional chest pain (angina), usually due to subendocardial hypoperfusion caused by increased right ventricular wall stress and myocardial oxygen demand but occasionally caused by dynamic compression of the left main coronary artery by an enlarged pulmonary artery. This risk is greatest for patients with a pulmonary artery trunk at least 40 millimeters in diameter

- Peripheral edema due to right ventricular failure, increased right-sided filling cardiac pressures, and extracellular volume expansion.

- Exertional syncope due to the inability to increase cardiac output during activity or reflex bradycardia that is secondary to mechanoreceptor activation in the right ventricle.

- Anorexia and/or right upper quadrant abdominal pain due to passive hepatic congestion.

Uncommon symptoms include a cough, hemoptysis, and hoarseness (Ortner syndrome). Compression of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve by a dilated main pulmonary artery causes the hoarseness.

Physical Exam

The most prominent features of the physical examination in patients with TR are those related to the regurgitant murmur and the development of right-sided heart failure. With severe right heart failure, the patient often looks cachectic, chronically ill, cyanotic, and occasionally jaundiced (reflecting hepatic dysfunction). If TR is due to left ventricular dysfunction, signs of left-sided heart failure may dominate. Patients with PH may develop physical signs as they progress from PH alone to PH associated with right ventricular failure/hypertrophy. The systemic venous hypertension caused by right ventricular failure can lead to a variety of findings, such as elevated jugular venous pressure, a right ventricular third heart sound, and a prominent V wave in the jugular venous pulse. Hepatomegaly, a pulsatile liver, peripheral edema, ascites, and pleural effusion also may exist. Some patients with PH due to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) develop edema even in the absence of right heart failure.

Jugular Veins

Distended and prominent jugular veins are apparent and reflect right atrial pressure elevation.

There is a presence of distinct “c-v” wave due to systolic regurgitation through the tricuspid valve into the right atrium. With the development of ventricular hypertrophy, a prominent “a” wave may emerge within the jugular venous pulse and may be accompanied by a right-sided fourth heart sound and either a left parasternal heave or a downward subxiphoid thrust.

Jugular venous distension may be more prominent with inspiration (Kussmaul sign), a result of the increase in venous return. This finding, however, may not be very obvious with marked venous distension.

Palpation

Palpation of the chest may reveal a dynamic right ventricular heave due to the dilated right ventricle. A sustained systolic left parasternal lift is most frequently appreciated in the presence of significant right ventricular hypertrophy. Long-standing, severe pulmonary arterial hypertension, whether precapillary (idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension or pulmonary valve stenosis) or postcapillary (mitral stenosis, cardiomyopathy), produces right ventricular hypertrophy and a sustained lower left parasternal lift. It may be associated with a palpable presystolic a wave preceding the right ventricular lift (heave); suggesting decreased right ventricular compliance. Epigastric and subxiphoid pulsations are usually abnormal and are related to right ventricular hypertrophy and dilation or the abdominal aortic aneurysm. However, in patients with emphysema, subxiphoid pulsations may not always indicate right ventricular hypertrophy.

A hyperdynamic but not sustained left parasternal systolic impulse may be palpable when right ventricular volume is increased, as with an atrial septal defect or TR. The left parasternal impulse becomes sustained during systole when pulmonary arterial hypertension is also present. When the TR is very severe, a pulsation may be detected along the right sternal border due to flow into the right atrium.

A left parasternal and mid-precordial systolic outward impulse, similar to that associated with right ventricular hypertrophy, can be palpable in the absence of right ventricular hypertrophy; for example, in patients with significant mitral regurgitation. The systolic pulsation appears to result from left atrial expansion due to mitral regurgitation pressing the anterior structures forward toward the anterior chest wall. In some patients with Ebstein's anomaly, a right parasternal systolic outward movement, presumably due to a large, ventricularized right atrium, is appreciated.

Cardiac Auscultation

Heart sounds

An S3, which may vary in intensity and with inspiration, is often associated with an extremely dilated right ventricle. An S4 may also be heard if there is significant right ventricular hypertrophy. The initial physical finding of PH is ordinarily the increased intensity of the second heart sound's pulmonic component which may become palpable. Patients with preserved right ventricular function, have a closely split or single second heart sound. Right ventricle failure (or a right bundle branch block) widens the splitting of the second heart sound. When there are other associated cardiac abnormalities, auscultatory findings of these conditions also may be appreciated.

Murmur

TR is classically associated with a holosystolic murmur that is best heard at the right or left mid sternal border or at the subxiphoid area. When the right ventricle is very enlarged, the murmur even may be appreciated at the apex. There is usually little radiation of the murmur, and a thrill is not palpable. However, the murmur of TR is often soft or absent, even when regurgitation is severe. Diastolic murmurs are usually absent in TR, although a diastolic rumble may be heard, particularly if there is associated tricuspid stenosis or when there is substantial blood flow across the tricuspid valve during diastole, which may occur with an atrial septal defect.

Maneuvers

Interventions that result in an increase in venous return, such as leg raising, exercise, or hepatic compression, will augment the murmur of TR. The murmur also may become louder after a premature beat and prolonged diastole. On the other hand, reducing venous return with standing or amyl nitrate will diminish the intensity of the murmur. In patients with pulmonary hypertension, the intensity of the murmur may change with changes in pulmonary artery pressure.

Respiratory variation in the intensity and duration of the murmur (Rivero-Carvallo sign) may be observed with mild to moderate TR. With inspiration, there is an increase in venous return to the right ventricle; as a result, the murmur of TR becomes louder and may become longer unless it is already holosystolic.

The respiratory variation may occasionally be augmented when the patient is standing and venous return is reduced. On the other hand, respiratory variation may not be appreciated in patients with severe TR or marked right ventricular enlargement and dysfunction.

Edema

Ascites and peripheral edema of variable severity may be present, and anasarca can occur in severe disease. There is frequent evidence of unilateral or bilateral pleural effusions, which are more common when the TR results from pulmonary hypertension secondary to a left-sided cardiac problem (valvular or myocardial).

Hepatomegaly

The liver is often enlarged and tender and may be pulsatile in severe TR. Occasionally, the systolic murmur may be transmitted to and heard over the liver (with a thrill).[8]

Evaluation

The focus in evaluation is on underlying disease processes that progressed to right ventricular hypertrophy.[9][10][11]

Chest Radiograph

Chest radiographs of patients with severe TR reveal cardiomegaly due to right ventricular enlargement. A prominent cardiac silhouette is observed on the right with the pulmonary artery view, and the enlarged right ventricle fills in the retrosternal space on the lateral film. Additional findings may include right atrial enlargement, the presence of an azygos vein, an upwardly displaced diaphragm, or the presence of pleural effusions.

When the cause of the TR is pulmonary hypertension secondary to a left-sided cardiac abnormality, other radiographic findings may be seen, particularly prominent right and left pulmonary artery hilar segments.

ECG Criteria

Right axis deviation (axis greater than 90 to 100 degrees) is often present with right ventricular hypertrophy. There also may be associated right atrial overload and ST-segment and T-wave abnormalities in the right precordial leads (formerly called “RV strain”), reflecting subendocardial ischemia or repolarization abnormalities of the right ventricular myocardium.

The RV forces become predominant in patients with right ventricular hypertrophy (especially due to a pressure load as with pulmonic outflow obstruction or severe pulmonary hypertension), producing tall R waves in the right precordial leads (V1 and V2), and deep S waves in the left precordial leads (V5 and V6). Because of the increase in the amplitude of the R wave and decrease in the depth of the S wave, the R:S ratio in V1 greater than 1 is suggestive of right ventricular hypertrophy. Differential diagnosis of increased R:S ratio in adults includes right bundle branch block, posterior wall myocardial infarction, Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern (especially due to lateral or postero-lateral left ventricular pre-excitation), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (septal hypertrophy), early precordial transition (counterclockwise rotation), normal or positional variant.

Obtaining an R:S ratio greater than 1 from a right-sided precordial lead (V3R or V4R) may be a more reliable indicator of right ventricular hypertrophy.

Thus, reported clues to the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy include the following:

- Right axis deviation (greater than 90)

- R in V1 greater than 6 mm

- R in V1 + S in V5 or V6 greater than 10.5 mm

- R/S ratio in V1 greater than 1

- S/R ratio in V6 greater than1

- Late intrinsicoid deflection in V1 (greater than 0.035 seconds)

- Incomplete right bundle branch block

- ST-T wave abnormalities ("strain") in inferior leads

- Right atrial hypertrophy/overload (“P pulmonale”)

- S greater than R in leads I, II, III, particularly in children (S1S2S3 pattern)

Patients with VSD and EKG evidence of right ventricular hypertrophy require evaluation to determine the cause (pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary stenosis, or double-chambered right ventricle).

Echocardiogram

Diagnostic testing is indicated whenever PH is suspected. The purpose of the diagnostic testing is to confirm that PH exists, determine its severity, and identify its cause:

- When a patient's echocardiogram is NOT suggestive of PH: Diagnostic evaluation should be guided by clinical suspicion. If the clinical suspicion for PH is low, evaluation of the patient's symptoms should be directed toward alternative diagnoses. Alternatively, if the clinical suspicion for PH remains high despite the echocardiographic findings, right heart catheterization (RHC) should be performed.

- When echocardiogram is suggestive of PH: No further testing for PH is required if there is enough left heart disease on the echocardiogram to explain the degree of estimated PH. However, additional diagnostic testing is required if there is either no evidence of left heart disease or the extent of left heart disease seems insufficient to explain the degree of estimated PH.

Echocardiography is the main diagnostic modality for evaluation of TR. The operator should examine the right ventricle using multiple acoustic windows, and the report should present an assessment based on both qualitative and quantitative parameters. It enables evaluation of the severity of TR, valve morphology, right chamber sizes and right ventricular function, estimation of pulmonary artery systolic pressure as well as an assessment of any concomitant left heart disease. Parameters that can be measured include RV and right atrial (RA) size, a measure of RV systolic function, as assessed by at least one or a combination of the following:

- Fractional area change

- DTI-derived tricuspid lateral annular systolic velocity wave

- Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

- RV index of myocardial performance

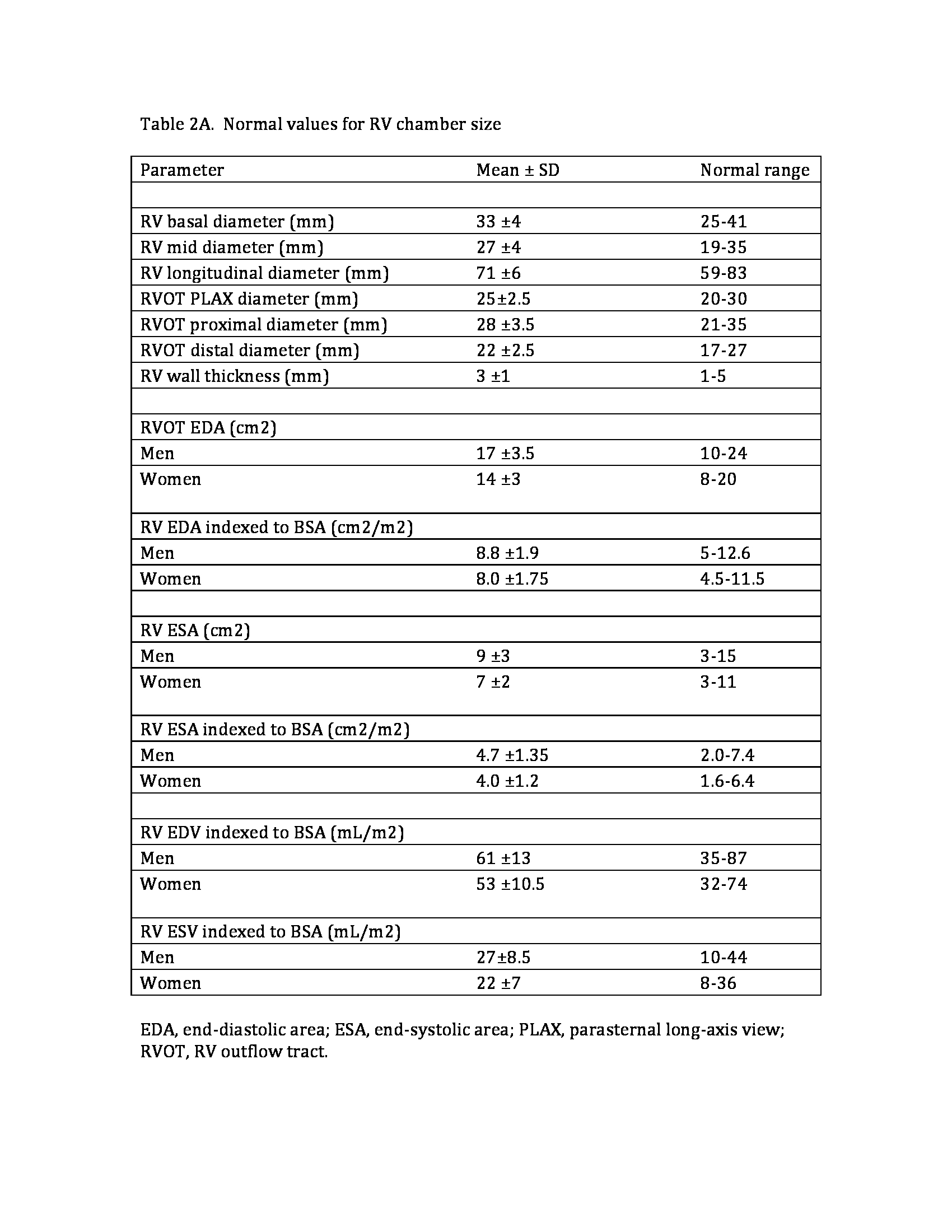

RV systolic pressure, typically calculated using the TR jet and estimation of RA pressure based on inferior vena cava size and collapsibility, should be reported when a complete TR Doppler velocity envelope is present. When feasible, additional parameters such as RV volumes and EF using three-dimensional echocardiography should complement the basic two-dimensional echocardiographic measurements. The new reference values according to the 2015 American Society of Echocardiography guidelines are displayed in Tables 2A and 2B.

Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging may be helpful if the echocardiographic evaluation is suboptimal or inconclusive for assessment of TR severity and right ventricular size and function. CMR enables quantitative assessment of tricuspid regurgitant volume, a regurgitant fraction (the ratio of TR volume to stroke volume), right ventricular volumes, and ejection fraction as well as evaluation of associated LV and mitral disease.

Cardiac Catheterization and Angiography

Cardiac catheterization and contrast right ventriculography are not helpful for the diagnosis or evaluation of TR in most patients. However, RHC of measurement of pulmonary pressures and pulmonary vascular resistance is appropriate in patients with TR when clinical and noninvasive data regarding pulmonary pressures are discordant. Left heart catheterization may be helpful to assess potential causes of functional TR (left-sided valve or myocardial disease with an elevated left atrial pressure). On the other hand, a diagnosis of PH requires RHC. PH is confirmed when the mean pulmonary artery pressure is 25 mm Hg or greater at rest. Clinical studies and additional information provided by RHC are necessary to then classify the patient into an appropriate World Health Organization (WHO) PH category (groups 1 through 5).

Right Heart Catheterization

RHC is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of PH and accurately determine the severity of the hemodynamic derangements. RHC is also helpful in distinguishing patients who have PH due to left heart diseases, such as systolic dysfunction, diastolic dysfunction, or valvular heart disease (pulmonary venous hypertension; post-capillary PH due to left-sided heart disease) (table 1).

Pulmonary Function Tests

Pulmonary function tests are performed to identify and characterize underlying lung disease that may be contributing to PH.

Overnight Oximetry

Overnight oximetry can identify nocturnal oxyhemoglobin desaturation. It is common in patients with PH and may prompt supplemental oxygen therapy during sleep.

Polysomnography

Polysomnography is the gold standard diagnostic test for sleep-related breathing disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea. It should be performed when the clinical suspicion for OSA is high or the results of overnight oximetry are discordant with clinical expectation.

Exercise Testing

Exercise testing is usually performed using the six-minute walk test, stress echocardiography, or cardiopulmonary exercise testing. The latter can be performed with gas exchange measurements, echocardiography, and/or RHC.

Ventilation-Perfusion Scanning

Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scanning is the preferred imaging study to evaluate patients for CTEPH. A normal V/Q scan accurately excludes chronic thromboembolic disease with a sensitivity of 96% to 97% and a specificity of 90% to 95%. When the V/Q scan suggests that chronic thromboembolic disease exists, pulmonary angiography is necessary to confirm the positive V/Q scan and to define the extent of disease. V/Q scans are an important part of the diagnostic evaluation because PH due to chronic thromboembolic disease is potentially reversible with surgery.[5][12]

Treatment / Management

In patients with severe TR and right-sided heart failure, loop diuretics are recommended for volume overload, including peripheral edema and ascites. Aldosterone antagonists may provide additional benefit, particularly in those with hepatic congestion with secondary hyperaldosteronism.

Most adults with TR have significant left-sided heart disease and treatment should be directed at the primary disease process. If heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction is present, standard therapy, including beta-blockers and agents that inhibit the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, are recommended.

Tricuspid valve surgery is suggested for patients with severe symptomatic TR despite medical therapy without severe right ventricular systolic dysfunction. When feasible, tricuspid valve repair is preferred to tricuspid valve replacement. However, repair is associated with significant risk of recurrent TR. For patients with mild, moderate, or greater functional TR who are undergoing left-sided valve surgery, concomitant tricuspid valve repair is advised. For patients with severe TR with or without symptoms and/or undergoing surgery for left-sided (mitral) valve disease, tricuspid surgery is recommended as noted in the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology and the 2012 European Society of Cardiology valvular disease guidelines. The choice of bioprosthetic versus mechanical prosthetic tricuspid valve should be individualized based on patient characteristics. A mechanical valve offers greater durability but requires anticoagulation to reduce the risk of thrombosis.

In patients with PH, primary therapy should be directed at the underlying cause of the PH. In addition, the need for diuretic, oxygen, and anticoagulant therapy should be assessed. Patients with persistent PH whose WHO functional class is II, III, or IV despite treatment of the underlying cause of the PH should be referred to a specialized center to be evaluated for advanced therapy. There is no single best approach to selecting an agent for advanced therapy. The strategy is to choose an agent based on multiple factors including WHO functional class, right ventricular function, hemodynamics, vasoreactivity test, and patient characteristics and preferences.[13]

Differential Diagnosis

- Left-sided heart failure: Left ventricular systolic and diastolic heart failure are well-known causes of peripheral edema, right upper quadrant pain from hepatic congestion, and syncope due to arrhythmias or insufficient cardiac output. Exertional chest pain may also occur. Left-sided heart failure and PH can be distinguished via echocardiography and/or right and left heart catheterization.

- Coronary artery disease: Myocardial ischemia is the most common cause of exertional chest pain, and it also can cause ischemia-induced arrhythmias with exertional syncope. Coronary artery disease is identified by stress testing and/or left heart catheterization.

- Budd-Chiari syndrome: Budd-Chiari syndrome refers to thrombosis of the hepatic veins and/or the intrahepatic or suprahepatic inferior vena cava. It causes peripheral edema due to venous outflow obstruction and right upper quadrant pain due to hepatic congestion. The syndrome can be identified by Doppler ultrasonography, CT, MRI, or venography.

- Liver disease: Acute and chronic liver diseases cause peripheral edema, and the former can also cause right upper quadrant pain. Liver disease can be detected by liver function testing and right upper quadrant ultrasound. Liver biopsy is the gold standard, but it is seldom necessary.

Staging

Table 1A. Updated Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension (Fifth World Symposium held in 2013 in Nice, France)

1. Pulmonary arterial hypertension

1.a Idiopathic PAH 1.b Heritable PAH 1.b.1 BMPR2 1.b.2 ALK-1, ENG, SMAD9, CAV1, KCNK3 1.b.3 Unknown 1.c Drug and toxin-induced 1.d Associated with: 1.d.1 Connective tissue disease 1.d.2 Schistosomiasis 1.d.3 Congenital heart diseases 1.d.4 Portal hypertension 1.d.5 HIV infection1′ Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and/or pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis1′′ Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN)

2. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease

2.a Left ventricular systolic dysfunction 2.b Valvular disease 2.c Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction 2.d Congenital/acquired left heart inflow/outflow tract obstruction and congenital cardiomyopathies

3. Pulmonary hypertension due to lung diseases and/or hypoxia

3.a Interstitial lung disease 3.b Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 3.c Other pulmonary diseases with mixed restrictive and obstructive pattern 3.d Alveolar hypoventilation disorders 3.e Sleep-disordered breathing 3.f Developmental lung diseases 3.g Chronic exposure to high altitude

4. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH)

5. Pulmonary hypertension with unclear multifactorial mechanisms

5.a Systemic disorders: sarcoidosis, pulmonary histiocytosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis 5.b Hematologic disorders: chronic hemolytic anemia, myeloproliferative disorders, splenectomy 5.c Metabolic disorders: glycogen storage disease, Gaucher disease, thyroid disorders 5.d Others: tumoral obstruction, fibrosing mediastinitis, chronic renal failure, segmental

BMPR (bone morphogenic protein receptor type II); CAV1 (caveolin-1); ENG (endoglin); HIV (human immunodeficiency virus); PAH (pulmonary arterial hypertension)

Table 1B. Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) Associated with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD)

Left-to-right shunts

- Correctable

- Non-correctable

Includes moderate to large defects; pulmonary vascular resistance is increased, systemic-to-pulmonary shunting is prevalent, cyanosis is not a feature.

Eisenmenger syndrome

- Includes extra- and intra-cardiac defects usually begins as systemic-to-pulmonary shunts and progress with time to a severe elevation of pulmonary vascular resistance and reversal (pulmonary-to-systemic) or bidirectional shunting; cyanosis, secondary erythrocytosis (due to hypoxia) and multi-organ involvement are present.

Post-operative Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- CHD is repaired, but pulmonary arterial hypertension can persist immediately after surgery or recur after surgery in the absence of significant postoperative hemodynamic lesions

Pulmonary arterial hypertension with coincidental CHD

Prognosis

The prognosis of PH is highly variable and depends upon the etiology and severity of PH.

- Etiology of PH: In general, in the absence of therapy, those with group 1 PAH have worse survival than groups 2 through 5. However, with therapy, patients with chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH; group 4), particularly surgically correctable CTEPH tend to have the best survival. Compared with those who had PAH, those with chronic lung disease associated PH (group 3) had worse survival at one year (80% versus 88%), 3 years (52% versus 72%), and 5 years (38% versus 59%). Patients with group 2 PH had similar survival rates to those with PAH.

- The severity of PH: In general, severe PH (e.g., mean pulmonary arterial pressure 35 mm Hg or greater), and/ or evidence of right heart failure have a poor prognosis.

While the clinical setting, particularly concomitant cardiovascular disease, influences survival in patients with TR, severe TR is an independent predictor of mortality.

Pearls and Other Issues

Clinicians also should be aware that apparent limitations in the accuracy of right ventricular hypertrophy criteria and conflicting results in the literature might reflect the fact that different pathophysiologic substrates give rise to very different ECG findings. Tall (normal duration) right precordial R waves (as part of R, RS, or QR morphologies) with right axis deviation, as noted above, are most likely to be associated with severe RV pressure overloads due to pulmonic stenosis (and its variants) or pulmonary hypertension from causes other than COPD (primary pulmonary hypertension or recurrent pulmonary emboli). Pulmonary hypertension due to severe COPD (emphysema) may be associated with very slow R wave progression, delayed precordial transition zone, and right axis deviation. In contrast, right ventricular hypertrophy due to a classic volume load state (ostium secundum atrial septal defect) may be associated with RV conduction delay and right axis deviation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of right heart failure is with an interprofessional team that consists of a cardiologist, pulmonologist, intensivist, internist and cardiac surgeon. In the outpatient setting, these patients are managed by the primary care provider and nurse practitioner. In patients with PH, primary therapy should be directed at the underlying cause of the PH. In addition, the need for diuretic, oxygen, and anticoagulant therapy should be assessed. Patients with persistent PH whose WHO functional class is II, III, or IV despite treatment of the underlying cause of the PH should be referred to a specialized center to be evaluated for advanced therapy. There is no single best approach to selecting an agent for advanced therapy. The strategy is to choose an agent based on multiple factors including WHO functional class, right ventricular function, hemodynamics, vasoreactivity test, and patient characteristics and preferences. The prognosis for patients with pulmonary hypertension is guarded. The key is to manage the primary cause. In patients with fixed pulmonary hypertension with right heart failure, the prognosis is very poor. In the clinical setting of concomitant cardiovascular disease, survival is influenced by TR,;severe TR is an independent predictor of mortality. [16][17][18](Level V)

(Click Image to Enlarge)