Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Thigh Sartorius Muscle

- Article Author:

- Benjamin Walters

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 9/17/2020 8:52:18 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Thigh Sartorius Muscle CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Thigh Sartorius Muscle

Introduction

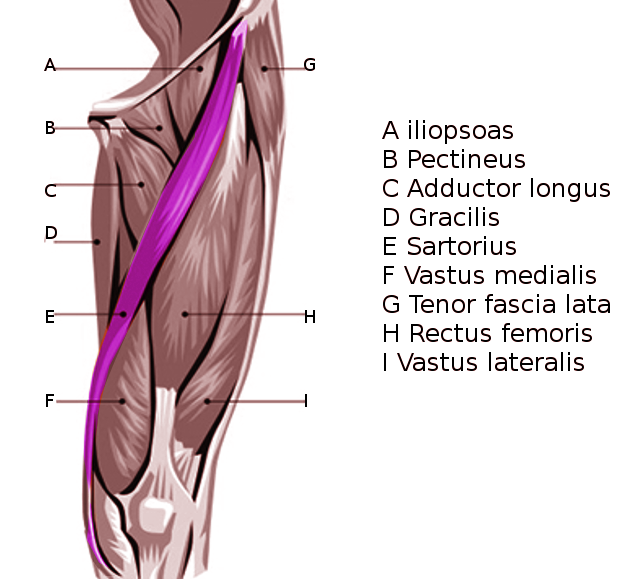

The sartorius is the longest muscle in the body, spanning both the hip and the knee joints. The word sartorius is derived from the Latin word sartor, which translates to patcher, or tailor, due to the way the individual will position their leg while working. It is the most superficial muscle in the anterior compartment of the thigh and travels obliquely from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the medial side of the proximal tibia at the pes anserine. The sartorius muscle acts synergistically in concert with the other musculature of the hip, thigh, and knee.

Structure and Function

The function of the sartorius is unique in that it can serve as both a hip and knee flexor. The origin for the sartorius is the anterior superior iliac spine, sharing this origin with the tensor fascia lata. At the hip, it acts to both flex the hip as well as externally rotate. Other hip flexors include, most dramatically, the iliopsoas muscle, and, to a lesser degree, the rectus femoris, tensor fascia lata, pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, and gracilis. Antagonists to flexion at the hip include the gluteus maximus, the hamstrings (specifically the long head of biceps femoris), and the semimembranosus and semitendinosus, which all act to extend at the hip.

The primary muscles responsible for internal rotation at the hip are the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus, but the tensor fascia lata also assists. Antagonists and external rotators of the hip include the piriformis, both the superior and inferior gemelli, both the obturator internus and obturator externus, and the quadratus femoris.[1]

The insertion for the sartorius muscle is the superior medial aspect of the tibial shaft, near the tibial tubercle. Two other tendons join it at its insertion: the gracilis and semitendinosus, to create the conjoined tendons known as the pes anserinus. At the knee, it acts to flex as well as internally rotate. Other knee flexors include the hamstrings, which are composed of the long and short head of biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus. The popliteus has some function in knee flexion, but more importantly as an internal rotator of the tibia. The antagonists to these muscles belong to the quadriceps muscle group, comprised of the rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, and vastus intermedius, all of which act to extend the knee.

Along with the popliteus as mentioned above, other internal rotators of the knee acting in concert with sartorius include the semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and gracilis. These muscles are opposed by the long and short heads of the biceps femoris, which act to rotate the knee externally.[2]

These synergistic movements of the muscles mentioned above performing with sartorius allow the leg to be moved into the figure-4 position, much like a tailor would position him or herself while working as described earlier.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to sartorius is mostly comprised of muscular branches of the femoral artery. Over half of the blood supply comes from these muscular branches of the femoral artery, but collateral flow does come from elsewhere. A study researching contributing blood flow to the sartorius demonstrated collateral blood flow arising from the superficial circumflex iliac artery, lateral circumflex femoral artery, superficial femoral artery, descending genicular artery, and superior medial genicular artery.[3]

Nerves

The sartorius is innervated by the femoral nerve, which is supplied by the nerve roots L2, L3, and L4. The femoral nerve innervates both the hip flexor and quadriceps muscle groups. The femoral nerve (motor divisions and branches) innervates the following muscles:

Anterior division, motor:

- Sartorius

- Pectineus

- Typically gets its innervation via the femoral nerve, although the obturator nerve is known to also provide additional innervation via cadaveric studies

- Iliacus

- Via muscular branches of the femoral nerve (specifically L1,L2,L3)

Posterior division, motor:

- Quadriceps muscle group (rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius)

The innervation to sartorius is derived explicitly from the anterior division of the femoral nerve. The posterior division supplies innervation to the muscles of the quadriceps. The pectineus nerve innervates the pectineus, which branches off the femoral nerve cephalad to the inguinal ligament. The femoral nerve also supplies sensation to the anterior thigh and medial leg.[4]

Clinical Significance

Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS) Avulsion

Young athletes are susceptible to ASIS avulsion injuries through the physis. These injuries typically occur secondary to indirect trauma via a sudden, forceful contraction of the sartorius, along with the tensor fascia lata. The ossification of the apophysis usually does not occur until age 21 to 25. Before this ossification occurs, there is a weak point at the muscle-tendon-bone interface, and it is susceptible to an avulsion. This commonly takes place while the hip is in an extended position, like sprinting or swinging a bat.

Avulsions of the ASIS are most often treated conservatively. This involves rest, stretching, protected weight bearing with the aid of crutches, and early range of motion. There are indications, however, for operative treatment of this injury. If there is displacement of the fragment, there is a risk of irritation, loss of strength, as well as healing of the fragment in a displaced position if the injury is treated by conservative means.

Open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) is indicated when the avulsion of the ASIS displaces by a distance of more than 2-3 centimeters. Painful non-unions are also an indication for surgical fixation. There are several different options, including lag screw and tension band fixation.[5]

Chronic Overuse Injuries

Much like other overuse injuries like tennis elbow, chronic overuse of the sartorius, along with the gracilis and semitendinosus, can create inflammation at the insertion point of the conjoined tendon of these three muscles. This inflammation can irritate the local tissue surrounding the tendon, including the bursa, a condition known as pes anserine bursitis. This is most commonly seen in male athletes in their fourth decade of life. These patients often involved in endurance sporting activities like cycling or running and complain of pain in the posteromedial aspect of the knee, directly at the pes anserine insertion. There are reports of underlying osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis as causes of chronic bursitis.[6]

Like avulsions of the anterior superior iliac spine, the vast majority of these injuries improve with conservative treatment. First-line treatment involves physical therapy, including stretching and strengthening. In cases with no apparent improvement with therapy alone, steroid injections can be used as adjunctive therapy.[7]