Schizencephaly

- Article Author:

- Poornachand Veerapaneni

- Article Author:

- Karthika Durga Veerapaneni

- Article Editor:

- Sisira Yadala

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 4:42:50 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Schizencephaly CME

- PubMed Link:

- Schizencephaly

Introduction

Schizencephaly is a rare congenital neuronal migration disorder characterized by the presence of a full-thickness cleft, lined with heterotopic gray matter, and filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which connects the pial surface of the cerebral hemisphere with the ependymal surface of the lateral ventricle.[1][2]

Schizencephaly was first described by Wilmarth in 1887.[2] The term was coined from the Greek word "schizen" 'to divide' and introduced by Yakovlev and Wadsworth in 1946, based on their work on cadavers,[3] that classified schizencephaly into two types:

- Type I (closed-lip): Cleft is fused, which prevents the cerebrospinal fluid passage.

- Type II (open-lip): A cleft is present, which permits CSF to pass between the ventricular cavity and subarachnoid space.

Schizencephaly can be either unilateral or bilateral.[2]

Recent literature classifies schizencephaly into three types, as the full thickness cleft containing CSF is not mandatory for the definition.[4]

- Type 1 (trans-mantle): No CSF-containing cleft on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but contains a trans-mantle column of abnormal gray matter.

- Type 2 (closed-lip): Presence of cleft containing CSF, but the lining lips of abnormal gray matter are abutting and opposed to each other.

- Type 3 (open-lip): Presence of cleft containing CSF. The lining lips of abnormal gray matter are not abutting each other.

Etiology

The exact etiopathogenesis of schizencephaly is not yet clearly understood in the scientific world. Possible etiological factors include exposure to teratogenic agents, viral infections prenatally, genetic, stroke in utero, and young maternal age.[5]

Some environmental exposures have been implicated: Teratogens such as alcohol, warfarin, or cocaine; viral infection, especially cytomegalovirus; as well as attempted abortion, hypoxia, amniocentesis, or chorionic villus biopsy, or maternal trauma, etc.[6]

Fetal intracranial hemorrhage caused by abnormal type IV collagen has also been implicated.[7]

Some genetic mutations have been reported as possible etiological factors for schizencephaly. The main genes identified in this regard are the following:

Epidemiology

Schizencephaly is a rare cerebral malformation with an estimated incidence of 0.54 to 1.54 per 100,000 live births.[2] The estimated prevalence is 1.48/100 000 births.[10] It is almost always sporadic. Only a few familial cases have been described, and there is no known gender predilection.[11] Schizencephaly can be more commonly seen in abandoned or adopted children, and that supports the possibility of exposure to in utero insults.[6] Schizencephaly also reported occurring more frequently in the fetuses of younger mothers.[10]

Pathophysiology

Schizencephaly results from abnormal neuronal migration a few weeks after gestation. There are four main malformations of cortical organization, lissencephaly, periventricular nodular hypertrophy, cobblestone malformations, and polymicrogyria. Abnormal neural migration could be incomplete, which could lead to heterotopia and lissencephaly, while over migration would result in cobblestone malformations, and anomalous cortical organization would lead to focal cortical dysplasia and polymicrogyria. Per the literature review, reported potential causes to include prenatal teratogenic exposures such as alcohol, warfarin, or cocaine.,etc., prenatal viral infections like CMV infection, intrauterine fetal stroke, and genetic mutations (COL4A1, EMX2, SHH, SIX3 genes). Other known risk factors of schizencephaly include illicit use of alcohol and narcotic substances, young maternal age, attempted abortion, amniocentesis or chorionic villus biopsy, or maternal trauma, etc.[1][5][6][7][8][9]

Histopathology

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of schizencephaly is a wide range. The patients might have normal cognition with seizure onset in adulthood. The patients can also have hemiparesis with mild developmental delay or severe cognitive impairment with quadriparesis.[6]

Clinical presentation depends on the type.

- Type I (closed-lip) has a milder course which can be asymptomatic or diagnosed only in adult patients and presents with epileptic seizures and mild motor deficits.[15]

- Type II (open lip), has a severe course, manifested by epilepsy (often refractory), intellectual disability, varying degrees of paralysis, hemiparesis in unilateral schizencephaly and quadriparesis in bilateral schizencephaly.[15]

The clinical features of patients with schizencephaly can be classified according to whether the finding is unilateral or bilateral.[2][16] Unilateral schizencephaly may present with contralateral hemiparesis and asymmetrical muscle tone. Bilateral schizencephaly may present with seizures, developmental delay, quadriparesis, and severe mental deficits.

Evaluation

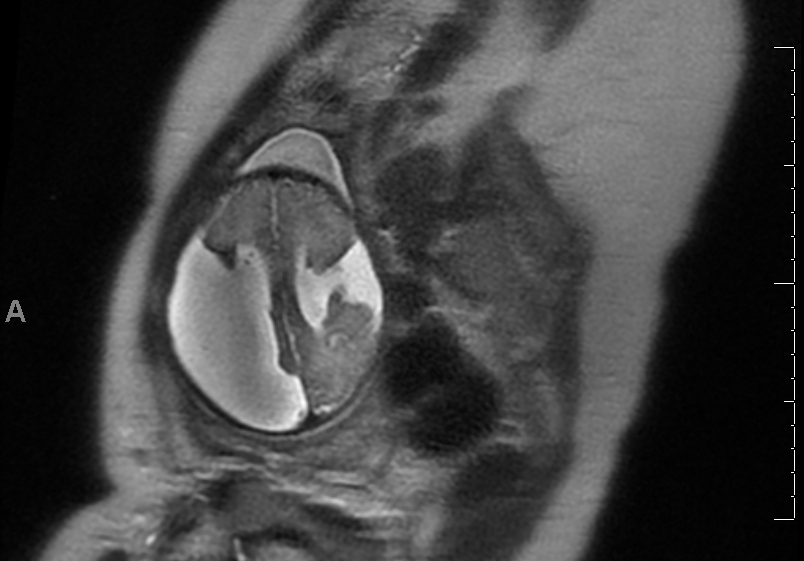

The diagnostic method of choice of imaging in schizencephaly is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Imaging shows a fluid-filled linear cleft lined with heterotrophic gray matter that extends from the pial membrane of the cortex to the ependymal surface in the ventricle.[15][17] Type 1 can be seen as a nipple-like out-pouching at the ventricular surface.[4] Computed tomography (CT) may also be useful, but it provides poorer images of the gray matter, which are the key factor in differentiating between schizencephaly and other fluid-associated CNS abnormalities such as arachnoid cyst, porencephaly, and hydranencephaly. The diagnosis may be suspected prenatally if clefts are viewed within the cerebral hemispheres by two-dimensional ultrasonography (2DUS).[18]

Epileptogenic zone on EEG may demonstrate the area of dysplastic cortex, which may be situated not only within the cleft but also in its vicinity or in the contralateral hemisphere.[15]

Associated anomalies include septo-optic dysplasia (SOD), optic nerve hypoplasia, absence of septum pellucidum, pachygyria, polymicrogyria, a heterotopia, and arachnoid cysts.[19]

Treatment / Management

The treatment for schizencephaly depends on multiple factors, including the signs and symptoms and severity of the condition.

Management is mainly supportive, which includes rehabilitation for motor deficits, intellectual disability, and seizure management. Surgery can be a choice in cases with hydrocephalus or raised intracranial pressure.[15]

Differential Diagnosis

- Focal cortical dysplasia may have a cleft on the cortex, not extending up to the ventricles.

- Grey matter heterotropia will be seen as a linear cleft, but periventricular grey matter generally bulges into the ventricle.

- Porencephaly extends from cortex to ventricles but is lined by gliotic white matter; some authors would refer to schizencephaly as 'true porencephaly.'[7][20]

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the size and type of the clefts.

- Type I (closed-lip) has a milder course. It can be asymptomatic or diagnosed only in adult patients and presents with epileptic seizures and mild motor deficits.[15]

- Type II (open lip) has a more severe presentation, manifested by epilepsy (often refractory), intellectual disability, varying degrees of paralysis, hemiparesis in unilateral schizencephaly, and quadriparesis in bilateral schizencephaly.[15]

Complications

Schizencephaly is a CNS malformation that most often presents as epilepsy. Though a majority of patients have well-controlled seizures, some patients may develop refractory epilepsy with uncontrolled breakthrough seizures and associated risks, including sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). In individuals with schizencephaly with large fluid-filled spaces, there may be the development of elevated intracranial pressure with associated complications such as herniation, and these patients may require surgical intervention with or without ventricle-peritoneal shunt placement. These surgical methods can be associated with complications such as bleeding, subdural hygroma, empyema, hydrocephalus, and infections like meningitis. If shunting performed, additional possible complications include endocarditis and shunt related renal damage.[15]

Pearls and Other Issues

Schizencephaly is a rare congenital neuronal migration disorder.

- Type I (closed-lip) can be asymptomatic or diagnosed in adult patients.

- Type II (open lip) is a severe malformation that can manifest by refractory epilepsy, intellectual disability, varying degrees of paralysis from hemiparesis to quadriparesis.

- Possible etiological factors include teratogenic exposures, viral exposures, genetic mutations, and intrauterine fetal stroke.

Risk factors of schizencephaly include young maternal age and the illicit use of alcohol and narcotic substances.

The diagnostic method of choice in imaging of schizencephaly is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The therapeutic management of both types of schizencephaly is conservative.

Surgical treatment is undertaken in some cases with concomitant hydrocephaly or intracranial hypertension.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The care of patients with schizencephaly should be with an interprofessional team approach. When a primary clinician evaluates a patient with development delay, referral to a pediatric neurologist is recommended. The interprofessional team may include a pediatrician, pediatric neurologist, pediatric neurosurgeon, nurse, and pharmacist. Type 1 (closed-lip) schizencephaly symptoms may not manifest until adulthood.[15] Therefore, it is recommended that an adult neurologist should gain familiarity with the pathophysiology, presentation, diagnosis, and management of schizencephaly.

(Click Image to Enlarge)