Septal Perforation

- Article Author:

- Brian Downs

- Article Editor:

- Haley Sauder

- Updated:

- 8/26/2020 1:18:26 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Septal Perforation CME

- PubMed Link:

- Septal Perforation

Introduction

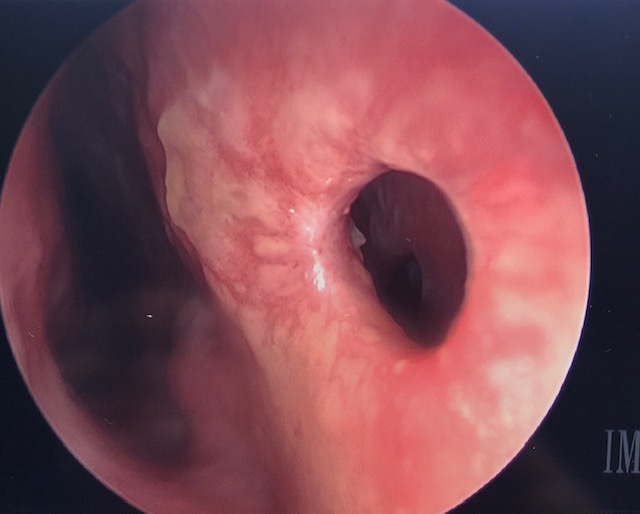

Nasal septal perforation is a full-thickness defect of the nasal septum. Bilateral mucoperichondrial leaflets and a structural middle layer (quadrangular cartilage, perpendicular plate of ethmoid, or vomer) comprise the three-layer divider between the right and left nasal cavities. Septal perforation occurs most commonly along the anterior cartilaginous septum. Symptoms can include nasal obstruction, whistling, epistaxis, crusting, pain, rhinorrhea, chronic rhinosinusitis, or foul smell.

Etiology

Nasal septal perforation etiologies include trauma, autoimmune (such as GPA), infectious (syphilis, fungal disease, tuberculosis), or neoplastic. Immunocompromised individuals may be at higher risk for opportunistic infections such as fungal infections. Iatrogenic septal perforation can occur after patient self-manipulation, after cautery for epistaxis, or after elective septoplasty. The reported incidence of septal perforation after septoplasty ranges from 0.5% to 3.1%.[1] Other causes can include intranasal drug abuse, steroid nasal spray, or vasoconstrictor nasal spray.

Epidemiology

Certain occupations are at higher risk. Historically, chrome platers suffered inflammation, erosion, and perforation after exposure to the offending chromic mist (Legge, 1902). Today, woodworkers and metal workers exposed to nickel dust are at higher risk of intranasal carcinoma.

Pathophysiology

The blood supply to the nasal septum arises from branches of the maxillary artery (sphenopalatine artery and greater palatine artery, superior labial artery (a branch of the facial artery), and the ophthalmic artery (anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries). The majority of the blood supply arises from branches of the maxillary artery which together supply the mucoperichondrial leaflets that cover each side of the septal cartilage. Any threat to the vascularity of these leaflets can jeopardize the viability of the underlying cartilage, predisposing to septal perforation. Septal perforations alter nasal airflow, creating turbulence which causes mucosal dryness which can predispose to crusting and epistaxis. Disturbance in laminar airflow can also cause subjective nasal obstruction or audible whistling noticeable during rest, sleep, or exercise.

Histopathology

Analysis of nasal septal biopsy may identify neoplasm, infectious organisms, or signs of vasculitis - all of which could potentially help identify etiology and aid in management.

History and Physical

A careful history will often provide information regarding etiology of septal perforation; this should include details regarding past nasal trauma, intranasal drug use (prescription, OTC, and illicit), nasal hygiene, pulmonary symptoms, renal symptoms, and autoimmune disease. Data collection should include details regarding the onset, duration, timing, and severity of symptoms, as well as delineation of prior therapies.

The physical exam should ascertain dimensions of the septal perforation in both horizontal and vertical dimensions, which can is doable in the clinic by using a headlight, a nasal speculum, and a pre-marked cotton-tipped applicator. The determination should be made of the relative vertical height of the septum as this can be a proxy for mucoperichondrium available for superiorly-based or bipedicled intranasal tissue rearrangement in the context of repair. Saddle deformity of the nasal dorsum should be noted as large perforations can threaten dorsal nasal support. Inflammatory conditions may cause granulation tissue or excessive crusting. Inspection for foreign material may give clues regarding illicit drug use. An intraoral exam can rule out palatal involvement. Inspection of the ear or temporal region (cartilage, temporalis fascia) can provide information regarding donor sites if repair becomes necessary.

Evaluation

Workup of septal perforation is dictated based on the clinical scenario. For example, in patients with an antecedent history of septoplasty after which perforation was noted, biopsy and laboratory workup is usually not indicated.

However, when the cause is less clear, biopsy of the perforation is performed and sent to pathology for permanent section. The patient should receive counsel that the biopsy will by definition cause enlargement of the perforation. The posterior edge is the area generally biopsied as horizontal enlargement usually does not adversely affect repair options.[2] Blood work includes ANCA, ANA, RF, ESR, CRP, FTA-ABS, ACE. Imaging may be indicated and can include CXR or CT scan of the sinuses. If tuberculosis is suspected, PPD or other tuberculosis testing may be warranted.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of nasal septal perforation can include medical and surgical management. Medical management includes providing humidification and emollients inside the nose to minimize discomfort, crusting, and epistaxis. Caution is advisable when using petroleum-containing products inside the nose to minimize aspiration and subsequent lipoid pneumonia. Saline and water-based gels are typically safer.

For patients who may be poor candidates for general anesthesia or formal repair, nasal septal prostheses are available. These mechanically cover the perforation and are generally fabricated of medical-grade synthetic material. Tolerance to the prosthesis is variable, and ongoing humidification is helpful. Prostheses have an overall low infection rate.[3]

Many types of surgical repair for nasal septal perforation have been described. These include the classic bilateral mucoperichondrial flap repair with an interpositional graft,[4] staged inferior turbinate flap,[5] acellular dermis graft,[6] auricular cartilage interposition,[7], facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap.[8] Not surprisingly, large septal perforations >20mm have a higher failure rate after the repair than smaller ones. Poor candidates for repair or patients with large perforations may benefit from posterior septal resection, essentially removing the posterior wall of the perforation with an attempt to mitigate symptoms.[9]

If autoimmune disease is present, caution is warranted. A recent systematic review of GPA and septal perforation recommended against septal perforation repair in this group, even in the setting of quiescent disease.[10]

Differential Diagnosis

Upon diagnosis of septal perforation, the three most critical primary causes to rule out are neoplasm, infectious disease, and autoimmune disease. These all represent treatable systemic diseases that require careful consideration and more in-depth treatment than symptomatic treatment and/or repair.

Surgical Oncology

Appropriate referrals are necessary if the biopsy shows neoplasm. The most common neoplasm of the nasal septum is squamous cell carcinoma. Other nasal septal neoplasms include adenocarcinoma and malignant melanoma.[11] First-line treatment is surgical excision with wide margins, and consideration may be given to radiation therapy if indicated. Performance of any planned repair after surgical excision of nasal septal carcinoma should be only after careful consideration with the counsel of a head and neck oncologist/oncologic surgeon.

Radiation Oncology

Appropriate referrals may be made if the biopsy shows neoplasm and the situation warrants adjuvant treatment.

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

As of this writing, there one clinical trial worldwide actively recruiting for nasal septal perforation repair. Based in China, the trial assesses the safety and efficacy of collagen membrane combined with human clinical grade umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells transplanted between septal mucosal leaflets.

Medical Oncology

As with radiation oncology, the appropriate referrals are necessary if the biopsy shows neoplasm and the situation warrants adjuvant treatment.

Staging

Although no formal or widely-accepted staging system exists for septal perforations, a “graduated approach” to repair has garnered support for small (less than 0.5 cm), medium (0.5 - 2 cm), and large (greater than 2 cm) perforations, with an eye toward systematically classifying this heterogeneous entity.[12]

Prognosis

Chronic crusting from septal perforation can lead to perforation enlargement, epistaxis, nasal pain, foul smell, and loss of dorsal nasal support (saddle nose deformity). These symptoms can have a negative impact on patient quality of life. With regular humidification measures, perforations can be managed medically and remain stable for years.

Complications

Failure to diagnose systemic disease or neoplasm would lead to a delay in care. Complications from septal perforation repair include persistent perforation, donor site scar, epistaxis, wound breakdown, nasal obstruction, need for revision, ozena, worsening symptoms, crusting, or whistling.

Consultations

Rheumatology - if autoimmune disease suspected/diagnosed

Infectious Diseases - if infectious etiology present

Medical Oncology - if neoplasm diagnosed

Radiation Oncology - if neoplasm diagnosed

Psychiatry - if chronic manipulation present

Deterrence and Patient Education

Overuse of vasoconstrictive nasal spray can erode nasal mucosa and predispose to septal perforation. For users of nasal steroid spray, the nozzle should be directed laterally to avoid showering the septum with local steroid which can cause thinning of the septal mucosa.

Medical management of septal perforation includes avoidance of manipulation and diligent humidification.

After septal perforation repair, care should be taken to avoid nose blowing for approximately one month after repair.

Pearls and Other Issues

Patients with septal perforation are often fastidious with nasal hygiene. After perforation repair, patients should minimize nasal manipulation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Caring for the patient with nasal septal perforation requires a team approach. Primary care physicians manage medical conditions such as hypertension, coagulopathy, or anti-platelet medications - which can worsen epistaxis. Nasal septal perforation can correlate with autoimmune disease and so consultation with a rheumatologist is often essential. If neoplasm is present, medical oncology and radiation oncology provide treatment recommendations. Anesthesiologists manage patients perioperatively, helping to control vital signs and ensuring a smooth recovery. Pharmacists give recommendations regarding postoperative pain control. (Level V evidence)