Silent Myocardial Ischemia

- Article Author:

- Zunaira Gul

- Article Editor:

- Amgad Makaryus

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 11:38:19 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Silent Myocardial Ischemia CME

- PubMed Link:

- Silent Myocardial Ischemia

Introduction

A heart attack commonly does not have apparent symptoms; silent myocardial ischemia can occur in the absence of chest discomfort or other anginal equivalent symptoms, e.g., dyspnea, nausea, diaphoresis, etc., with ST-segment changes on EKG, reversible regional wall motion abnormalities, or perfusion defects on scintigraphy studies. MI occurs due to multiple factors resulting in an imbalance between consumption and production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), causing ATP depletion leading to a cascade of biochemical events. Silent myocardial ischemia (SMI) obtained recognition at the beginning of the 20th century. About 70% to 80% of transient ischemic episodes do not present with anginal chest pain or any other symptoms (silent ischemia). Lack of pain in silent myocardial infarction (MI) increases morbidity and mortality since patients do not seek medical treatment in a timely fashion.[1][2]

Etiology

Patient classification is as one of three types of silent ischemia:

- Type I: This is the least common form and occurs in completely asymptomatic patients with CAD (which may be severe) in the absence of anginal symptoms.

- Type II: This type occurs in patients with documented previous myocardial infarction.

- Type III: This is the most common form and occurs in patients with the usual forms of chronic stable angina, unstable angina, and vasospastic angina.

Diabetes mellitus (DM): Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a significant risk factor for coronary artery disease and correlates with a higher incidence of SMI. Cardiac autonomic dysfunction is the main culprit in diabetic patients which involves pain receptors, afferent neurons or higher areas of the brain.[3][4]

Studies have shown that atherogenic dyslipidemia strongly correlates with an increased risk of SMI and silent CAD in patients with DM and the management of atherogenic dyslipidemia might help to reduce the high residual burden of cardiovascular disease.[5]

In surgery: There is a relatively high incidence of perioperative MI in the geriatric population. Studies have shown that patients who underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery had episodes of SMI detected by Holter monitoring. In the intensive care unit: Critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) admitted for noncardiac causes are also at risk of acute myocardial ischemia. Transient myocardial ischemia and advanced age are significant predictors of cardiac events. Sleep apnea: Obstructive sleep apnea carries correlations with myocardial ischemia (silent or symptomatic), cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, transient ischemic attack, and stroke.

Epidemiology

Studies have shown that the incidence rate of SMI is higher in men than in women. There is an increased risk of coronary heart disease deaths and all-cause mortality among both men and women with SMI. But there is a potentially greater increased risk among women.[6]

Pathophysiology

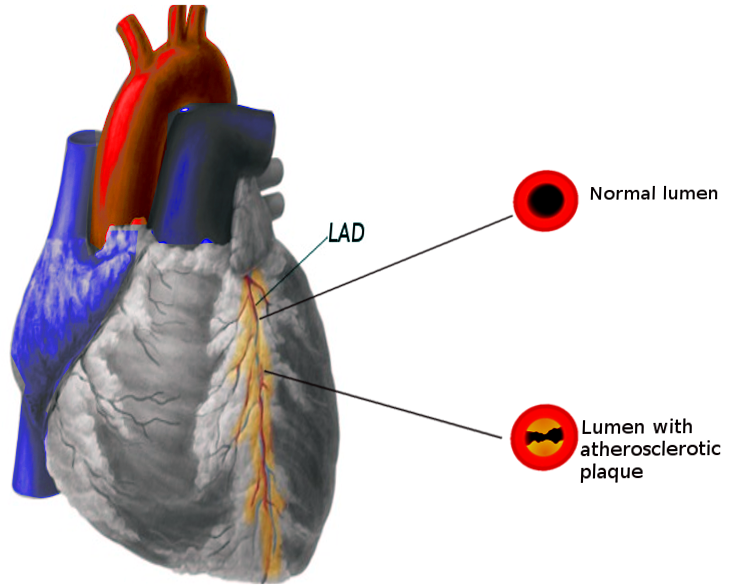

A myocardial infarct is mainly caused by rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque in any of the blood vessels supplying oxygen to the heart. Pathophysiology involved in this process includes movement of inflammatory cells in the vessel wall, engulfment of cholesterol products causing these macrophages to become foam cells, releasing growth factors which causes fibrin and smooth muscles to become part of the plaque. Plaques may have a thin or thick fibrous cap, rupture of these plaques causes devastating injury.[7]

Histopathology

Histological findings in the setting of acute MI are as follows;

- Characteristic histological features within the first 24 hours of insult include; coagulation necrosis of cardiomyocyte, neutrophilic infiltration, accumulation of RBCs in the interstitial spaces and interstitial edema. Eosinophilic appearing ischemic cardiomyocytes with loss of the cross-striations and loss of the nuclei. Within the next 24 to 48 hours, coagulative necrosis establishes completely. After 3 to 5 days, there is a loss of myocyte nuclei and striations in the central portion of the infarct. By 5 to 7 days, macrophages and fibroblasts appear. At 1 week, the number of neutrophils starts to decline, and granulation tissue establishes with lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration.

- Healing continues and, may be complete as early as 4 weeks or may require 8 weeks or longer to complete depending on the extent of necrosis. Sometimes, borders of larger infarct heal leaving the central area unhealed with mummified myocyte for extended periods.

- If reperfusion occurs early within 4 to 6 hours, there is a possibility that infarct would be sub-endocardial without transmural extension. Macrophages appear by day 2 to 3, and by day 3 to 5 fibroblast appears, with early signs of healing. As compared with that of non-reperfused infarcts, subendocardial infarcts heal early. They may undergo full healing as few as in 2 to 3 weeks. While some larger infarcts and those who take longer to be reperfused, beyond 6 hours show extensive areas of hemorrhage.[8][9]

History and Physical

Ischemic chest pain has been the hallmark of the clinical presentation of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Patients may present with absolutely no history of myocardial infarction or angina in the past, with previous myocardial infarction or with angina besides asymptomatic ischemic episodes. The history of presenting illness (HPI) and physical examination provide an immediate source of information for physicians to stratify the patients for further workup. Pertinent history in these patients would include past medical history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, prior coronary artery disease (CAD), or presence of other risk factors for CAD. Physical examination can be benign in these patients.

Evaluation

Treatment / Management

Medical Therapy: Beta blockers appear to be most effective and also improve outcomes. Although beta-blockers produce the greatest reduction in the number and duration of ischemic episodes, calcium channel blockers are also effective. Monotherapy with calcium channel blockers should primarily be used in patients with a specific identified pathogenic mechanism which is expected to respond better to calcium channel blockers (e.g., vasospastic angina), or if a patient is intolerant of beta blockers. Aspirin (antiplatelet therapy) and statin (lipid-lowering therapy) are also used.

Psychotherapy: Mental stress can provoke silent ischemia; especially in patients with underlying coronary artery disease. Data suggests a possible benefit from behavioral stress reduction in such patients.

Revascularization: Decision regarding the need for coronary artery revascularization are rarely if ever, based exclusively on the finding of silent myocardial ischemia. There are limited data evaluating the efficacy of coronary revascularization in the treatment of silent ischemia. The study showed no significant difference in mortality between the groups who underwent revascularization and those who continued medical therapy (19.1 and 18.3 percent, respectively).[12][13]

Differential Diagnosis

Differentials of epigastric or chest symptoms include CAD, aortic dissection, valvular abnormalities, myocarditis, lung pathologies, musculoskeletal etiology or those involving gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The proper history and physical examination help to narrow down the differentials.[14]

Prognosis

Those with a history of silent myocardial ischemia have a higher incidence of new coronary events than those with no silent ischemia, suggesting an aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic approach for these patients. Older persons present with atypical symptoms associated with acute MI which include dyspnea, neurologic and GI symptoms. By controlling modifiable risk factors and changing lifestyle one can improve the quality of life.[10]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients should be referred to cardiac rehabilitation programs to help them control modifiable risk factors, teach them how to deal with their stress, anxiety/depression, and restore exercise capacity after prolonged hospitalization for myocardial infarction. This approach will help to decrease morbidity and mortality of patients. Risk factors for coronary artery disease should be treated aggressively in a patient with diabetes. The best approach would be to perform screening ECG during their yearly follow-ups.[15]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of silent MI is an interprofessional. Often the diagnosis is missed or delayed, and hence appropriate referral to a cardiologist should be made. Patients should receive education about the control of modifiable risk factors; smoking cessation, lowering blood cholesterol, control of hypertension, diabetes, maintaining ideal body weight, regular exercises, control of stressors in their lifestyle, dietary modifications, and medication compliance. They should be advised regular follow-ups as by controlling these risk factors one can improve the quality of life and hence the long-term survival.[16]

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Figure 1 Small foci of coagulative necrosis can be recognised on haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections: ischaemic myocytes typically show the hypereosinophilia that characterises early phases of coagulative necrosis. (A) The ischaemic myocytes are located in the left side of the panel; (B) the ischemic myocytes are positioned bottom left; (C) low magnification view showing a small area of acute myocardial infarction in which granulocyte infiltration is clearly visible among the myocytes showing coagulative necrosis (squared area and (D), inset at higher magnification). The front of the myocardial ischemia is in the top half of the figure.

Contributed by PubMed