Anatomy, Skin (Integument)

- Article Author:

- Wilfredo Lopez-Ojeda

- Article Author:

- Amarendra Pandey

- Article Author:

- Mandy Alhajj

- Article Editor:

- Amanda Oakley

- Updated:

- 10/28/2020 1:07:08 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Skin (Integument) CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Skin (Integument)

Introduction

The skin is the largest and primary protective organ in the body, covering the body's entire external surface and serving as a first-order physical barrier against the environment. Its functions include temperature regulation and protection against ultraviolet (UV) light, trauma, protection from pathogens, microorganisms and toxins. The skin also plays a role in immunologic surveillance, sensory perception, control of insensible fluid loss, and homeostasis in general. The skin is also highly adaptive with different thicknesses and specialized functions in different body sites. This article will discuss the anatomy of the skin, including its structure, function, embryology, blood, lymphatic, and nerve supply, surgical and clinical significance. [1][2]

Structure and Function

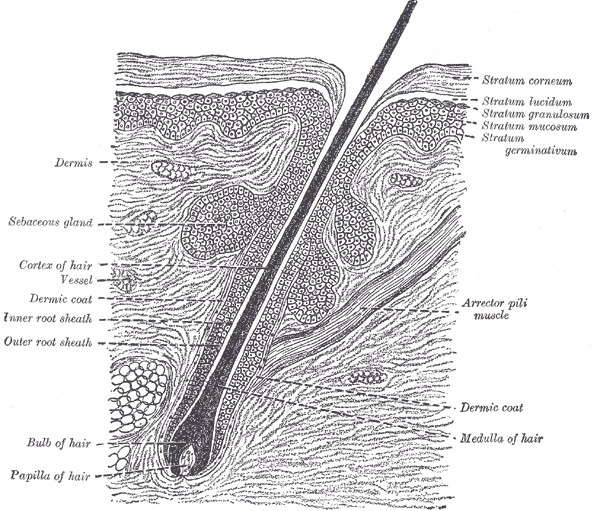

The skin is primarily made up of three layers. The upper layer is the epidermis, the layer below the epidermis is the dermis, and the third and deepest layer is the subcutaneous tissue.

- The epidermis, the outermost layer of skin, provides a waterproof barrier and contributes to skin tone.

- The dermis, found beneath the epidermis, contains connective tissue, hair follicles, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and sweat glands.

- The deeper subcutaneous tissue (hypodermis) is made of fat and connective tissue.

The epidermis is further divided into 5 layers on thick skin like the palms and soles (stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, stratum lucidum, and stratum corneum, while in other places the epidermis has 4 layers lacking the stratum lucidum).

The dermis is divided into two layers, the papillary dermis (the upper layer) and the reticular dermis (the lower layer).

The functions of the skin include:

- Protection against microorganisms, dehydration, ultraviolet light, and mechanical damage. Skin is the first physical barrier that the human body has against the external environment.

- Sensation to pain, temperature, touch, and deep pressure.

- Mobility allowing smooth movement of the body.

- Endocrine activity. The skin initiates the biochemical processes involved in Vitamin D production, which is essential for calcium absorption and normal bone metabolism.

- Exocrine activity by the release of water, urea, and ammonia. Skin secretes products like sebum, sweat, and pheromones, and also exerts important immunologic functions by the secretions of bioactive substances such as cytokines.

- Immunity development against pathogens.

Regulation of Temperature. Skin participates in thermal regulation by the conservation or release of heat and helps to maintain the body’s water and homeostatic balance. [1][2]

Embryology

Embryologically, the epidermis originates from the surface ectoderm. It is infiltrated with pigment-producing cells known as melanocytes, which originate from the neural crest. Other cell types normally present in the epidermis include keratinocytes, antigen processing Langerhans cells, and Merkel cells, (tactile receptors that sense pressure changes at the bottom of the epidermis).

The dermis is embryologically derived from the mesoderm and contains connective tissue macromolecular components and cells, including elastic fibers, collagen, nerves, blood vessels, adipocytes (fat cells), and fibroblasts. [1][2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The skin is highly vascularized and is supplied by plexuses found between the reticular and papillary layers of the dermis. The blood supply originates from an extensive network of larger blood vessels and capillaries that extend from regional branches of the systemic circulation to local sites throughout subcutaneous tissue and dermis, respectively.

There is an extensive lymphatic framework that runs alongside many of the skin’s blood vessels, particularly those attached to the venous end of the capillary networks. [3]

Nerves

Several skin receptors play specific roles in our ability to physically perceive the changes in the external environment.

- Meissner receptors detect light touch.

- Pacinian corpuscles perceive deep pressure and vibrational changes.

- Ruffini endings detect deep pressure and stretching of the skin’s collagen fibers.

- Free nerve endings located in the epidermis respond to pain, light touch, and temperature variations.

- Merkel receptors associated with the Merkel cells respond to sustained light touch induction over the skin.

Dermatomes are areas of skin mainly supplied by a single spinal nerve. There are 8 cervical nerves contributing to the dermatomes (except for C1), 12 thoracic nerves, 5 lumbar nerves, and 5 sacral nerves. Each of these nerves relays sensation (including pain) from a particular region of the skin to the brain.[4]

Muscles

Arrector pili muscles, the smallest skeletal muscles of the body, are found in all areas of the skin that contain hair follicles. These tiny muscular structures control the positioning of hairs and the activity of sebaceous glands in response to environmental induction, such as heat and abrasion. The arrector pili muscles contract and raise the hairs under conditions of stress when the sympathetic nervous system is activated such as during the fight or flight response. [1][2]

Physiologic Variants

The multiple layers of the skin are dynamic, shedding and replacing old inner layers. The thickness of skin varies based on its location, age, gender, medications, and health affecting the skin’s density and thickness. The varying thickness is due to changes in the dermis and epidermis. Thick skin is found in the palms and soles where there is marked keratinization and the stratum lucidum layer. Thinner skin is found on eyelids, axillae, and genitals, as well as the mucosal surfaces exposed to the external environment such as oral mucosa, vaginal canal, and other selected internal body surfaces.

Mostly due to the effects of androgens, adult males typically have thicker skin than females in most areas of the body. Children have thin skin, which gradually thickens until the fourth decade of life, affected by the concentration of sex steroids, general health, and hydration. The skin begins to thin again during the fifth decade of life, primarily due to changes in the dermis with loss of epithelial appendages, elastic fibers, and ground substance, among others. Genetic and environmental factors also affect the skin thickness. For example, a person with an occupation requiring much outdoor exposure to the sun and ultraviolet radiation will tend to show premature skin aging signs sooner than a person working indoors. Genetics also influence the natural skin contour; for example, people of African-American descent typically exhibit thicker and more lustrous skin compared to people of Anglo-Saxon ancestry.[1][2][3]

Surgical Considerations

Surgical incisions usually are made along the relaxed skin tension lines to improve healing and reduce scarring, especially during cosmetic surgical procedures.

These lines are also referred to as “cleavage lines”. They closely match the alignment of bundles of collagen fibers within the dermis. Their discovery followed the investigations of the Austrian anatomist Karl Langer, who noticed a consistent pattern of ellipsoidal lines over the skin surface of the studied cadaver specimen after repetitively puncturing their skin with a circular tool. His reports referred to the lines as elongated creases following singular ellipsoidal patterns in different directions based on the specific body areas.

The relaxed tension lines used by surgeons today have been adapted from Langer’s lines. Relaxed tension lines have a completely different functional rationale and anatomical etiology from dermatomal lines and surface wrinkles.[5][6]

Clinical Significance

The skin has many areas of clinical and cosmetic significance including anatomical variations, congenital defects, signs of aging, skin cancers, acne, infections, and numerous inflammatory disorders.

Lines and creases develop over the bony articulations (joints) and high friction surface areas, such as the knees and elbows. Contraction of the skin causes wrinkles that lie perpendicular to the skeletal muscles underneath the skin, which act as vectors of physical tension or stress points.

The three most common skin cancers encountered are basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Skin cancers are associated with UV damage, sporadic mutations, and genetic alterations.

Acne is one of the most common skin disorders and results from the plugging of hair follicles with exfoliated keratinocytes and oil. It is common in youth, but can also affect adults. The extent and severity are variable including comedones, papules, pustules, nodules, cysts, and scars.

Skin infections include cellulitis, erysipelas, and impetigo caused by staphylococcal and streptococcal bacteria.

Other Issues

Dermatomes and Referred Pain

In the human body, the sensory fibers carrying pain stimuli are arranged into dermatomes, which are segmentally distributed across the entire body surface (illustration below). Dermatomes develop embryologically.

A dermatome functionally represents how sensory information (e.g., pain) travels from a particular skin receptor type (e.g., nociceptor) to the corresponding peripheral nerve then connects to a specific spinal nerve (cervical; C1–C8, thoracic: T1–T12, lumbar: L1–L5 and sacral: S1–S5), reaching the spinal cord where the signals ultimately ascend to the brain.[6][7][8]

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)