Smith's Fracture Review

- Article Author:

- Jeremy Schroeder

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 11:05:53 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Smith's Fracture Review CME

- PubMed Link:

- Smith's Fracture Review

Introduction

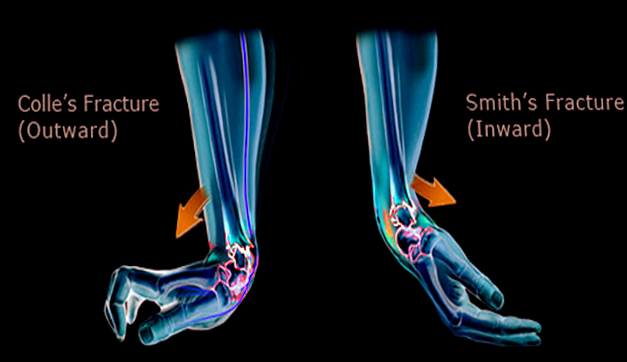

A Smith fracture is an eponym for an extraarticular fracture of the distal radius featuring a volar displacement or angulation of the distal fragment. It is also known as a reverse Colles fracture since the more common Colles fracture features a dorsal displacement of the distal fracture fragment. The Smith fracture was named by Irish surgeon Robert William Smith in 1847, who incidentally followed Abraham Colles as Professor of Surgery at Trinity College in Dublin and performed and published Colles’ autopsy. However, this injury was first named for French Physician Jean-Gaspard-Blaise Goyrand (1746-1814) and is commonly known as a Goyrand fracture in French literature.[1] The fracture also has the name in some references of reverse Barton fracture, which is an intraarticular fracture with volar displacement of the distal radius fragment.

Etiology

Distal radial fractures are often the result of a fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH). Colles fractures are frequently associated with a typical FOOSH injury. On the other hand, Smith fractures commonly occur either as a fall onto a flexed wrist or as a direct blow to the dorsal aspect of the wrist.[1] More common than initially thought, volar displacement of the distal radius can occur with a fall onto the palm of the hand.[2]

Epidemiology

The distal radius is the most common fracture site in the upper extremity. With over 600000 cases annually in the United States alone, distal radial fractures account for more than 16% of all adult fractures and 75% of forearm fractures.[3][4][5][2] Distal radial fractures are the second most common fracture in the elderly.[6] However, Smith fractures make up approximately 5% of all radial and ulnar fractures combined. The highest incidence of Smith's fractures is in young males and elderly females. Almost all distal radius fractures arise in children sustaining high-energy falls and osteoporotic seniors who suffer low-energy falls.[7]

In the elderly population, distal radial fractures are the second most common fracture, second only to hip fractures.[6] Between the ages of 64 to 94, women are six times more likely than men to sustain this type of fracture.[8] Data appears to support a direct correlation between low-energy trauma-induced distal radius fracture and decreased bone mineral density.[9]

History and Physical

The physical exam may reveal a deformity of the distal forearm, but the direction of angulation- dorsal (Colles) or volar (Smith) is difficult to discern on visualization. Also, present on the exam are swelling, pain, and decreased ROM. One of Smith’s first diagnostic criteria was a deformed wrist with swelling visible on the volar side and the prominence of the ulna along the dorsum of the wrist.[1] In addition to the volar displacement of the distal fragment, disruption of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) and the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) often occurs.[10] There may also be an association of ulnar styloid base fractures.[11]

Evaluation of the extremity's neurovascular status is imperative. A compromise would necessitate immediate attempts at closed reduction. Up to 15% of these fractures may show symptoms of acute carpal tunnel syndrome (ACTS) from compression to the median nerve.[12] Less commonly, but still present neurological concerns include both radial and ulnar nerve compression.[13] Another cause of neurovascular compromise seen in Smith fractures and other distal radius fractures is acute compartment syndrome of the forearm.[14][15]

Evaluation

A wrist radiograph series is adequate for the characterization of a distal wrist fracture and can differentiate between a Colles and Smith fracture. Typically, orthogonal views (AP, lateral) are adequate. However, additional radiographs of the wrist such as traction, oblique, and fossa lateral views along with advanced imaging, may offer vital information about the injury to include associated soft tissue injuries.[16] The latter is rarely necessary in most clinical situations. In certain instances, a CT may be useful in situations of extensive comminution or intra-articular fracture patterns. In these scenarios, a CT can help define, and best appreciate not only the pattern of injury but also help the surgeon to plan for operative reduction strategy.

In general, radiographic interpretation should comment on the presence of a distal radial fracture with volar angulation, the fracture location (extra-, juxta-, or intra-articular), the degree of angulation, and the degree of displacement. The radiographic interpretation should also comment on carpal malalignment, carpal fractures, as well as the articulation of the radio-lunate and radio-scaphoid joints.

Treatment / Management

Smith fractures present a challenging management issue for the astute clinician/provider. The ultimate goal of successful treatment is, of course, to restore alignment. Many times given the shear fracture pattern, these fractures are not amenable to nonoperative management. Nonetheless, the provider needs to obtain post-reduction x-rays to ensure appropriate alignment of the fracture because even two millimeters or more articular step-off increases risk for the development of degenerative arthritis.[17] Careful decision-making is required to determine treatment via conservative closed reduction and casting vs. operative measures, which include percutaneous fixation, external fixation, or open reduction internal fixation (ORIF). To guide this, established criteria for acceptable alignment. Indications for operative management include[18][19]:

- Dorsal or volar comminution

- Intra-articular involvement

- Instability post-reduction

- Surface angulation greater than 20 degrees

- Articular surface step-off over 2 mm

- Radial shortening greater than 5 mm

Conservative Approach

The mainstay of treatment of non displaced and stable distal radius fractures is closed reduction followed by immobilization. While the more common fracture pattern (Colles) required a characteristic hyperextension deformity with a volar directed force to maintain reduction with splinting, the opposite is necessary for Smith fracture reductions. The wrist, therefore, is reduced and splinted in extension. The closed reduction is performed under procedural sedation, hematoma block, regional nerve block, intravenous regional/Bier block, or general anesthesia.[20] There is no supported difference in the splinting method for stable distal radius fractures.[21] However, there is no evidence to support the use of thermoplastic splints or braces for acute distal radius fracture.[22] Regardless of the chosen splinting method, AAOS clinical guidelines recommend weekly radiographs for the first three weeks after reduction/immobilization and before the cessation of splinting/casting.

A trial of closed reduction with percutaneous pinning (CRPP) is another option. Kirschner wires are minimally invasive, low-cost, and offer good functional outcomes for two or three-part fractures.[23] However, this is not a good option for poor bone quality (i.e., osteoporosis), multiple fragments of comminution. Complications include injury to the tendons, nerves or vasculature, pin migration, fracture settling, and a pin site track infection.

A third option is external fixation. With the rise of ORIF, popularity has significantly declined. The principal concept is that external fixation utilizes ligamentotaxis to maintain appropriate positioning of the fracture fragments. Currently, this largely serves for stabilization of patients with polytrauma before the transfer, or for initial management of an open fracture with significant tissue loss.[24] However, in the instance specifically to Smith fractures and the volar displacement of the distal radial fragment, maintenance of appropriate reduction is challenging. Complications include pin track infection and pin loosening. Also, higher reported rates of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) can present. The belief is that over the distraction of the carpus may play a role in this.[25]

As stated above, ORIF has become the most favored method of treatment, especially with the advancement of locking plates; this is the best choice for a fracture that is unstable or not reducible.[26] The three main categories of internal fixation are dorsal, volar, and fragment specific fixation. Although Cochrane reviews and AAOS guidelines do not prioritize one method over another, for an ORIF surgery, a volar plate appears to be favored, as it not only reduces the risk of extensor tendon rupture but also believed to better preserve blood supply of the metaphysis.[27][28][18] With the Smith fracture pattern, there is essentially no role in dorsal plating. An addition to the nature of the volar displaced distal fragments alone, dorsal plating is associated with increased rates of extensor tendon injury and rupture.[29] Fragment specific fixation offers custom construction combinations based on the needs of the individual fracture pattern utilizing small plates and clips. They are typically more time-intensive, technically demanding, and often require more than one approach.

Differential Diagnosis

- Colles Fracture - extraarticular distal radius fracture with dorsal displacement/angulation

- Barton Fracture - intraarticular distal radius fracture with dorsal displacement/angulation

- Reverse Barton Fracture - intraarticular distal radius fracture with volar displacement/angulation

- Die-Punch Fracture - fracture of the articular surface with depression of the lunate facet

- Chauffer’s Fracture - avulsion fracture of the radial styloid

- Distal Radioulnar Joint (DRUJ) disruption- injury to the sigmoid notch of the radius and the lunate facet

- Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex (TFCC) tear - damage to the cartilaginous structure on the ulnar aspect of the wrist

- Galeazzi Fracture - fracture to the distal third of the radius with disruption of the DRUJ

Staging

Smith fractures divide into three types:

- Type I - most common type, accounting for about 85% of cases, is an extraarticular fracture through the distal radius

- Type II - less common, accounting for approximately 13%, is an intraarticular oblique fracture, also referred to as a reverse Barton fracture

- Type III - uncommon, less than 2%, is a juxta-articular oblique fracture

Prognosis

Patients with a closed reduction have good outcomes, with functional healing around six weeks.[23] There is low-level medical evidence about long-term outcomes of early postoperative mobilization. For athletes, stable fixation, edema management, early mobilization with rehabilitation, and functional bracing is essential for an early return to sport.[30]

Complications

As with most fractures, the potential for complications exist. One concern complication is a malunion; this may occur with a residual volar displacement or shortening of the distal radius. A malunion can result in a cosmetic abnormality known as a garden spade deformity. It may also narrow or distort the entryway into the carpal tunnel, with resultant delayed carpal tunnel syndrome. In the elderly population, there appears to be a correlation between decreased bone density and trouble maintaining closed reduction. This situation increases the risk for further displacement despite appropriate immobilization In the instance of malunion.[31] There have been reports that elderly patients with unstable distal radius fractures treated by closed means have a 50% malunion rate [32]. In these instances, an osteotomy can improve function and appearance.[33]

As stated above, volar angulation of the distal radius may also result in ACTS, but even conservative management with excess flexion or extension may also cause compression to the median nerve.[34] A less common complication in traumatic settings is the entrapment of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon with malunion in both conservative and ORIF surgeries.[35][36][37] Late rupture of the EPL is also commonly cited in the literature.[38][39] Another vexing complication is the development of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), reported in up to nearly 40% of fractures.[40]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Stable fractures are typically immobilized 4 to 8 weeks followed by rehab and bracing another 4 to 6 weeks until pain-free ROM and have achieved normal strength. Unstable fractures are often immobilized 6 to 12 weeks, followed by work until regaining motion and strength.[41]

Pain management is always a concern in the postoperative periods. One study showed that transdermal buprenorphine and codeine-acetaminophen provided superior pain control than celecoxib in the six weeks following ORIF with a volar locking plate, thus citing better compliance and faster functional recovery.[42] However, the clinician should make every attempt to limit the use of opioid analgesics outside the acute management environment. This strategy requires discussion from the operative team as well as primary care providers to offer expectation management of pain control in the postoperative period.

AAOS 2009 Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend adjuvant treatment with vitamin D for the prevention of CRPS development following distal radius fractures (moderate level of recommendation).[20]

Preventive measures of distal radius fractures mainly revolve around fall prevention, which is especially relevant in the elderly population.

Deterrence and Patient Education

A Smith fracture is a break to the end of the radius. The end part of the bone, which forms part of the wrist joint, is displaced or angled in the direction of the palm of the hand. Often, this injury occurs by a fall to the back of a flexed wrist but can occur in any fall to an outstretched hand. This type of injury will typically show swelling, bruising, and deformity towards the wrist, showing the prominence of the top of the forearm with the wrist appearing to be a step below. It is important to check for any numbness of the hand and ensure blood flow to the hand is not compromised by squeezing the fingernail and seeing if color returns promptly. The arm and hand should be immobilized, and the patient should get transported to advanced medical care where the area can be assessed by a healthcare provider, and X-rays are obtainable. The appearance of the broken bone on X-ray will determine the best course of management; this may be simple casting if the site of the break can be reduced and is in a good position. However, if the fracture is more significant, it may require surgical correction.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Smith fractures are the second most common type of distal radius fractures but are significantly less common than the Colles fracture. This type of fracture may display significant volar displacement or angulation of the distal fragment and hand relative to the main shaft — the majority of patients with Smith fracture present in the emergency department. Once admitted, the emergency department physician should consult with the radiologist for appropriate imaging studies and inform the orthopedic surgeon. Nurse practitioners who see these patients in urgent care clinics should not attempt to manage these fractures on their own as any residual displacement or angulation after reduction can lead to enormous morbidity. This approach without a specialist can commonly lead to acute carpal tunnel syndrome due to compression on the median nerve or compromise of vascular status. It is essential to assess neurovascular status at primary presentation and attempt reduction if necessary. If there is significant displacement or angulation, comminution, or the fracture site remains unstable after reduction attempts; outcomes show significant improvement with open reduction internal fixation of the radius as opposed to conservative casting. This fixation typically occurs with volar plating of the radius. Irrespective of the treatment, most patients need aggressive hand rehabilitation to restore muscle strength and joint function.

Orthopedic specialty-trained nurses will participate in the treatment and subsequent management, alerting the clinician to any concerns regarding patient compliance, medication use, or lack of progress. Physical therapists may also be called upon to work with these patients to restore full function to the affected limb. Recovery is gradual, but some patients may continue to have pain and diminished mobility depending on the type of fracture and treatment. The pharmacist should educate the patient on pain management which can be significant. Only through open communication between the interprofessional team can the morbidity of Smith fracture be lowered. [Level 5]