Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Nerves

- Article Author:

- Thomas Anderson

- Article Editor:

- Bruno Bordoni

- Updated:

- 7/31/2020 3:17:44 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Nerves CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Nerves

Introduction

The nerves of the forearm are complex due to the various nerve branches and the muscles that reside in the upper extremities. The forearm is composed of the radius bone laterally and the ulna bone medially. The four main joints of the forearm are the humeroulnar, humeroradial, and proximal and distal radioulnar joints.[1] A fibrous syndesmosis joint connects the radius and ulna and divides the forearm into anterior flexor and posterior extensor compartments. Muscular components in the anterior compartment of the forearm are the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, and pronator quadratus. Muscular components in the posterior compartment of the forearm are the brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor pollicis longus, extensor indicis, and supinator.[2] The nerves in the forearm derive from branches of the brachial plexus and the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. The five branches of the brachial plexus are the musculocutaneous, axillary, median, ulnar, and radial nerves.[3] All contribute to the innervation of the forearm except the axillary nerve. The branches from these four main nerves are the anterior interosseus, posterior interosseus, lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm, deep branch of radial nerve, superficial branch of radial nerve, dorsal cutaneous branches of the ulnar and median nerves, and palmar cutaneous branches of the median and ulnar nerves.

Structure and Function

The entire upper limb consists of the shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand. The function of the forearm is to serve as a bridge between the motion of the arm and the wrist and hand. The nerves of the forearm are ultimately responsible for innervating the muscles of the forearm. In addition to motor function, the nerves of the forearm provide afferent cutaneous sensation to the forearm, wrist, and hand.

The nerves carry a lot of information: electrical, biochemical (immune substances, growth factors, and hormones). The nerves participate in the metabolism of the tissue in which they pass.

Embryology

The entire human body derives from either ectoderm, mesoderm, or endoderm. Nerves specifically come from ectoderm. The neural tube and neural crest cells form from ectoderm. These structures will eventually become the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves.[4]

The spinal and brain nerves begin their development around the end of the first embryonic month. During this period, the neuroblasts of the basal lamina of the spinal cord emit neurites, applying themselves to developing myotomes. These are the primordial motor fibers intended to constitute the anterior roots of the spinal nerves. The sensory component begins to form around the second embryonic month.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply

The radial and ulnar arteries supply most of the blood to the forearm. These two arteries branch from the brachial artery just below the antebrachial fossa.[5] The radial artery is lateral, and the ulnar artery is medial. After the radial artery branches from the brachial artery, it travels over the pronator teres muscle lateral to the flexor carpi radialis. The radial artery gives off the radial recurrent and muscular branches distally. After the ulnar artery branches off the brachial artery, it travels under the ulnar head of the pronator teres lateral to the adjacent ulnar nerve. The ulnar artery branches into the anterior ulnar recurrent, posterior ulnar recurrent, common interosseous, and muscular branches. The venous drainage of the forearm is via the cephalic, basilic, radial, and ulnar veins. The cephalic vein gives the median cubital vein branch, which unites with the basilic vein. The cephalic vein meets the axillary vein forming the subclavian vein. The radial and ulnar veins drain into the basilic vein. The basilic vein drains into the axillary vein. The blood supply to the nerves in the forearm comes from the vessels that course nearest each nerve.

Lymphatic

The majority of lymphatic drainage from the upper limb drains into the axillary lymph nodes. There are five groups of axillary lymph nodes; central, lateral, posterior, anterior, and apical nodes. The drainage from the upper limb mainly travels to the lateral nodes, also known as the brachial and humeral nodes.

Nerves

The brachial plexus carries the majority of the innervation to the forearm; however, a small amount of sensory innervation comes from the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve.[6] The brachial plexus derives from the ventral rami of spinal nerves C5 through T1. The brachial plexus is divided into five sections as it courses distally; five nerve roots, three trunks, six divisions, three cords, and finally into five branches. This article will focus on the branches of the brachial plexus that deal specifically with the forearm.

Medial Antebrachial Cutaneous Nerve

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve forms as a branch of the medial cord from nerve roots C8-T1. This nerve travels anterior to the medial epicondyle subcutaneously and provides sensation to the medial forearm.[7]

Musculocutaneous Nerve

The musculocutaneous nerve forms from the C5-C7 nerve roots.[8] It travels in the subcutaneous tissue above the brachioradialis muscle. This nerve provides motor innervation to the biceps, brachialis, and coracobrachialis. The musculocutaneous nerve gives rise to the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm as it passes lateral to the biceps tendon. This nerve supplies sensation to the radial distribution of the forearm.

Radial Nerve

The radial nerve forms from the C5-T1 nerve roots. It provides motor innervation to the anconeus, brachioradialis, and extensor carpi radialis longus muscles.[9] After entering the forearm between the brachioradialis and brachialis, the radial nerve divides into the superficial and deep branches. After the deep branch pierces the supinator muscle, it branches into the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN). The PIN provides sensation to the posterior forearm and the dorsal wrist. It provides motor innervation to the deep and superficial extensors of the posterior compartment and the extensor carpi radialis brevis.

Median Nerve

The median nerve forms from the C5-T1 nerve roots. The median nerve travels under the biceps aponeurosis between the two heads of the pronator teres. There is no sensory component provided by the median nerve. The median nerve provides motor innervation to the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, and flexor digitorum superficialis. The only muscle in the anterior compartment not innervated by the median nerve is the flexor digitorum profundus. This muscle receives innervation from the ulnar nerve.[10] The anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) branches off the median nerve and passes under the arch of the flexor digitorum profundus.[11] AIN provides sensation to the volar wrist capsule and motor innervation to the deep flexors in the anterior compartment.

Ulnar Nerve

The ulnar nerve forms from the C8-T1 nerve roots. It travels down the arm and over the medial epicondyle. There is no sensory distribution provided by the ulnar nerve in the forearm. The ulnar nerve delivers motor innervation to the flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar half of the flexor digitorum profundus.[12] The nerve travels posteriorly and enters the forearm through the cubital tunnel. Dorsal and palmar cutaneous nerves branch off the ulnar nerve, roughly 5 cm proximal to the wrist.[12] The ulnar nerve continues into Guyon’s canal, where it divides into the deep and superficial branches.

Physiologic Variants

The musculocutaneous nerve may be bilaterally absent; the median nerve can innervate muscles that are usually innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve or a portion of the lateral cord of the brachial plexus. The musculocutaneous nerve can perform anastomosis with the median nerve.

The radial nerve (superficial branch of the radial nerve) can remain superficial to the brachioradialis muscle during its path, confusing itself with the medial or lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerves. The radial nerve can have anastomosis with the ulnar nerve, bilaterally, or only on one side.

The ulnar nerve has, like the other nerves of the forearm, various anatomical variations in its path and with anastomosis with the radial and median nerve.

Surgical Considerations

In surgery, knowledge of the anatomy of the forearm nerves is crucial when it comes to repairing or reconstructing boney or muscular defects. Proper technique and understanding of structures in the forearm help ensure no motor or sensory damage occurs. Some common procedures done to the forearm are ORIF of fractures, osteotomy, tendon repair, and carpal tunnel release. When surgically approaching the forearm through a volar approach, the internervous plane is a landmark to help guide dissection. The proximal internervous plane lies between the brachioradialis muscle and the pronator teres muscle. Distally, the internervous plane lies between the brachioradialis muscle and the flexor carpi radialis muscle.[13] Knowledge of the specific location and path of nerves is important to all physicians, but it is specifically important for orthopedic surgeons who are trying to realign a fracture.

Clinical Significance

Damage to nerves that supply the forearm could originate anywhere along the brachial plexus. Damage to the brachial plexus, known as brachial plexopathy, can result from trauma, inflammation, tumor, radiation, or bleeding. [3] This would present clinically as a combination of pain, loss of sensation, and motor weakness.

Cubital tunnel syndrome results from compression and damage to the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel. The cubital tunnel is the space on the dorsal medial aspect of the elbow. This syndrome causes tingling down the ulnar aspect of the forearm and into the 5th finger and ulnar half of the 4th finger. Nearly half of patients with cubital tunnel syndrome will show improvement with conservative management.[14] Conservative treatment includes splinting and analgesia. Patients that fail conservative management may require surgical cubital tunnel decompression.

Compartment syndrome is another noteworthy surgical consideration that could have detrimental effects on the function of the forearm. This syndrome occurs when swelling in a particular area compresses the vessels and nerves in the same region. The most common etiology of compartment syndrome in the forearm is fractures of the forearm bones. Signs and symptoms of this condition are remembered by the five P's: pain out of proportion to exam, pallor, paresthesias, pulselessness, and paralysis. A change in pressure from diastolic and compartment pressures that is less than 30 mmHg indicates compartment syndrome. [2] If the patient has unequivocally positive findings on physical exam, surgeons may forgo getting compartment pressures and initiate treatment. Compartment syndrome is a surgical emergency that requires an immediate fasciotomy. A fasciotomy is a surgical procedure where an incision is made in the skin, and blunt dissection is conducted to reach the fascia surrounding all the compartments of the forearm. The fascia is then cut to release the tension created by the swelling.

Understanding the innervation of the muscles of the forearm and the action of the forearm muscles is important clinically. When there is a lesion to a nerve, the normal function of the muscles that specific nerve innervates will be abnormal. This abnormality is deducible through proper history and physical exam, which allows the physician to provide treatment effectively.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

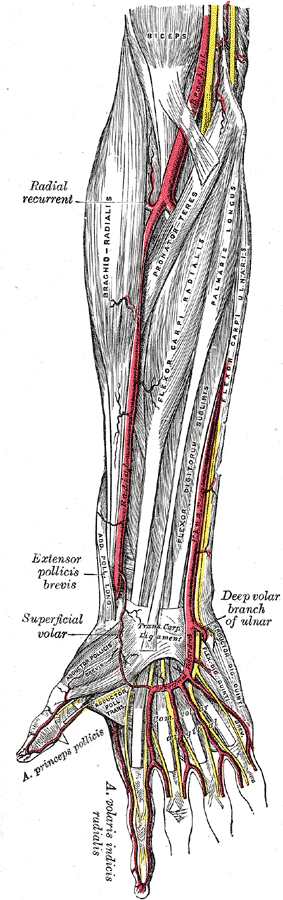

Muscles and Arteries of the right forearm and hand, Biceps, Brachial Artery, Racial recurrent, Brachioradialis, Pronator teres, Flexor carpi radialis, Palmaris longus, Flexor digitorum sublimis, Flexor carpis, Extensor pollicis brevis, Superficial volar, Abductor pollicis brevis, Adductor pollicis transversus, Abductor digiti quinti, Flexor digit quinti brevis, Yellow lines represent nerves.

Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates