Zygomatic Arch Fracture

- Article Author:

- Jeffrey Bergeron

- Article Editor:

- Blake Raggio

- Updated:

- 6/29/2020 1:44:31 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Zygomatic Arch Fracture CME

- PubMed Link:

- Zygomatic Arch Fracture

Introduction

The zygoma is a bone that provides vital contributions to both the structure and aesthetic of the midface and articulates with several bones of the craniofacial skeleton. The zygoma and its articulations comprise the zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC). Fractures of the zygomatic arch (ZA) or any of its bony articulations can cause significant functional and cosmetic morbidity. The management of the zygomatic arch and ZMC fractures should be patient-specific but range from simple observation to open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF).

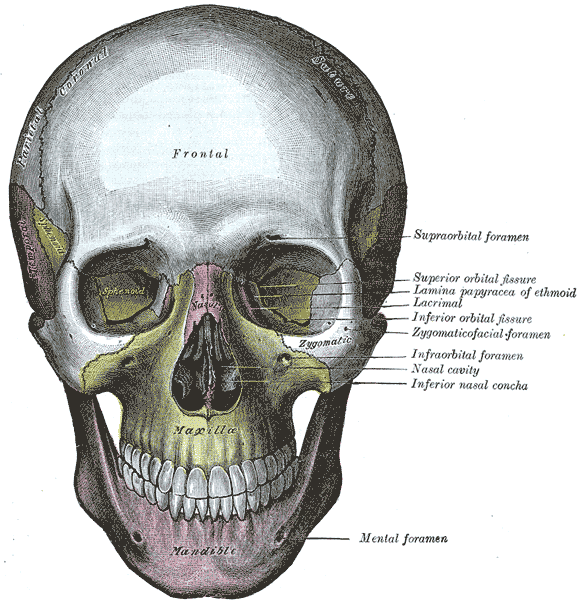

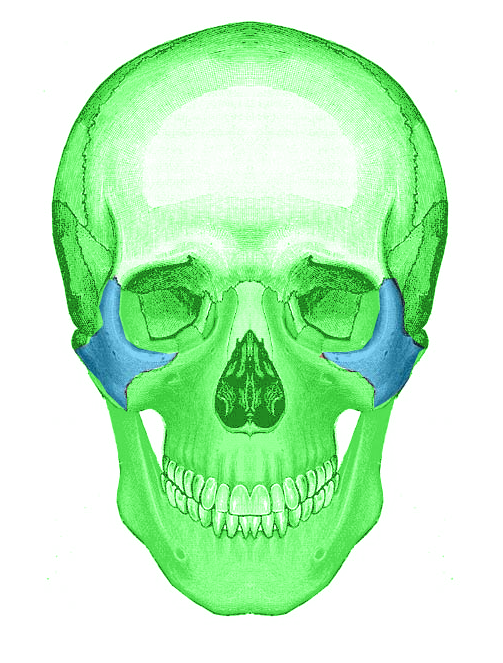

Anatomy

The zygoma is the most anterolateral projection of the midface. It plays a key role structurally as it absorbs and dissipates forces away from the cranial base. The zygoma also comprises a significant portion of the inferior and lateral orbital walls; thus, fracture of the zygoma warrant investigation into fractures of the orbit.

The zygoma has four articulations, referred to as the ZMC complex:

- Zygomaticotemporal (ZT) suture - The temporal process of the zygoma articulates with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone to form the anterolaterally projected zygomatic arch (ZA)

- Zygomaticomaxillary (ZM) suture and the infraorbital rim (IOR)

- Zygomaticofrontal (ZF) suture

- Zygomaticosphenoidal (ZS) suture

NOTE: Fractures of the ZMC complex may be mistakenly referred to as "tripod fractured," though the correct terminology is, in fact, "tetrapod fracture," given the four articulations of the zygoma as stated above.

Neuroanatomy

Paresthesia of the face is a common sequela of a ZMC fracture given its proximity to sensory nerves such as the infraorbital nerve, the zygomaticofacial nerve, and the zygomaticotemporal nerve (all branches of cranial nerve V2).

- The infraorbital nerve exits the maxilla via the infraorbital foramen, medial to the articulation of the maxilla, and the zygoma. The infraorbital nerve detects sensory input from the cheek, upper lip, nose, and anterior maxillary dentition.

- The zygomaticofacial and zygomaticotemporal nerves transmit sensory input from the lateral cheek and anterior temporal area, respectively. They are branches of the zygomatic nerve, which arises in the pterygopalatine fossa and enters the orbit via the inferior orbital fissure and travels along the lateral orbital wall. The zygomaticofacial and zygomaticotemporal branches then exit via identically named foramina in the zygoma.

Severe ZMC fractures may also result in an ipsilateral facial palsy since the facial nerve is intimately associated with the zygomatic arch. The facial nerve's frontal branch emerges from the parotid gland within the parotid-masseteric fascia and crosses superficial to the zygomatic arch in the innominate fascia deep to the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS). The frontal branch then transitions to the undersurface of the temporoparietal fascia where it travels to innervate the frontalis muscle.[1]

Muscular Anatomy

The temporalis originates along the temporal line of the parietal and frontal bones and travels medially to the zygomatic arch to insert on the coronoid process of the mandible. It also has attachments to the zygoma.

The masseter originates on the inferior aspect of the zygoma and zygomatic arch and inserts on the angle of the mandible.

The zygomaticus major and minor are muscles of facial expression that originate on the zygoma and insert near the corner of the mouth to assist with commissure elevation.

Other landmarks

Tubercle of Whitnall: The attachment site of the lateral canthal tendon located on the medial surface of the frontal process of the zygoma.

Etiology

Fractures of the zygoma are almost always the result of high impact trauma. The most common mechanisms are assault, motor vehicle collisions, falls, and sporting injuries.

Epidemiology

Most zygomatic fractures occur in men between the ages of 20 and 29. ZMC fractures are common, as estimates suggest that ZMC fractures comprise 25% of facial fractures.[2]

History and Physical

History

It is crucial to ascertain the mechanism and timing of the injury. Note whether the injury was caused by blunt or penetrating trauma, as penetrating trauma is more likely to involve deeper-lying neurovascular structures.[2] One should ask about prior facial trauma or facial surgeries, which may make fracture repair more difficult.

Physical

As with any trauma patient, it is important to start the examination with an evaluation of the "ABCs." Ensure the patient has an adequate airway, is breathing spontaneously, and that any bleeding is under control. It is also vitally important to "clear" the cervical spine for any associated injury. Inspect the face, noting any obvious asymmetry, lacerations, and ecchymosis of skin. Ipsilateral epistaxis is common and requires controlling if severe. An ophthalmologic exam should be performed, including visual acuity, visual fields, and extraocular movements. In a patient with a ZMC injury, the facial flattening may be apparent from a birds-eye view, which is caused by depression of the malar eminence; however, the facial flattening may get obscured by overlying soft tissue edema. The clinician should note the position of the globe. Enophthalmos may be visible from a worms-eye view. The face should be palpated, noting any bony step offs or mobility of the underlying craniofacial skeleton. A comprehensive cranial nerve examination should be completed, paying special attention to facial movement and sensation.

Evaluation

After a comprehensive history and physical examination, imaging is almost always necessary if a zygomatic arch or ZMC fracture is suspected. Historically, the Waters view plain film was used to evaluate ZMC fractures. A computed tomography (CT) scan is now the gold standard imaging modality. The 3-dimensional reconstruction is particularly useful for preoperative planning. There may also be a role for the intraoperative use of CT to assess the adequacy of fracture reduction, but there is no strong evidence to support the routine use of this practice.[3]

Classification of ZMC Fractures

Various classification systems have been used to categorize ZMC fractures further. Below is a widely used system proposed by Zingg[4]:

- Type A: an incomplete zygomatic fracture that involves one pillar

- 1: zygomatic arch fracture

- 2: lateral orbital wall fracture

- 3: infraorbital rim fracture

- Type B: all four pillars are fractured (a complete tetrapod fracture) with the zygoma remaining intact

- Type C: a multi-fragment zygomatic fracture, wherein all four pillars are fractured plus the body of the zygoma is fractured

Treatment / Management

Management of ZMC fractures can broadly classify into three categories: medical management, closed reduction, and open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF). Management of ZMC fractures is controversial and requires tailoring to each case.

Medical Management

Zygomatic fractures are usually observable if there is minimal or no displacement of fracture segments. Additionally, medical management may be the choice if other comorbidities preclude safe surgery. No strong evidence supports the use of prophylactic antibiotics in upper and midface fractures, though some surgeons prescribe a 5 to 7-day course of antibiotics, particularly if a communication exists with the maxillary sinus. If prescribed, antibiotics should cover sinonasal flora.[5]

Operative management

The indications for operative management of zygomatic arch and ZMC fractures are to restore the form and function of the ZMC. Fractures of the ZMC or zygomatic arch can often lead to unsightly malar depression, which should be corrected to restore a normal facial contour. ZMC fractures can also cause significant functional issues, including trismus, enophthalmos and/or diplopia, and paresthesias of the infraorbital nerve. A suspected globe injury is a contraindication to operative management of ZMC fractures and should be diagnosed/addressed before any surgical intervention to repair the zygomatic arch or ZMC fracture sites.

A principle of facial fracture repair includes the ability to reduce and/or fixate fractures that involve the facial buttresses to restore the structural integrity of the midface. Several methods exist to repair zygomatic arch and ZMA fractures, though closed reduction may be adequate for simple, low-velocity injuries of the zygomatic arch (see TYPE A1 below) that are non-displaced or minimally displaced and remain stable after initial attempts of reduction[2]. ORIF should be the choice for fractures that are comminuted or are likely to be unstable after reduction. Typically, profile titanium mini-plates are commonly used to fixate the fracture sites, working in a manner to repair fractures from laterally to medially and from stable to non-stable segments. Absorbable plates may also be used for fixation in cases where follow-up is unlikely, but such plates should not be routinely used as absorbable plates are structurally weaker in biomechanical studies.[6]

Herein we summarize a management algorithm based on Zingg's classification system of ZMC fractures as described above (see EVALUATION) [7]:

- Type A1 (zygomatic arch fracture) - Nondisplaced fractures of the zygomatic arch are often observable, whereas displaced fractures of the zygomatic arch require reduction, which is possible via a Gillies approach via a temporal incision, a transcutaneous Caroll-Girard screw directly over the depressed fracture site, or a Keen approach via a transoral incision in the maxillary vestibule. Isolated arch fractures that are not stable after reduction can be splinted externally with cardiac wires, or plated via a coronal incision.[8]

- Type A2 (Lateral orbital wall fracture) - Reduction and fixation of this area are best via a lateral brow incision or a blepharoplasty incision. Small mini-plates provide adequate stabilization of such fractures.

- Type A3 (Infraorbital rim) - The infraorbital rim (IOR) should be reduced and plated to restore its normal contour, and the optimal approach is via a transconjunctival incision or lower eyelid incision.

- Type B (Tetrapod fracture) - Mildly displaced tetrapod fractures may occasionally be reducible via a Gillies or Keene approach. Most tetrapod fractures, however, remain unstable after such reduction attempts and ultimately require ORIF with single point fixation (zygomaticomaxillary buttress or the zygomaticofrontal suture), two-point fixation (the ZM buttress and the zygomaticofrontal suture), and three-point fixation (the IOR). Finally, the zygomatic arch can be plated via a coronal incision or pre-existing lacerations as the fourth point of fixation if necessary.

- Type C (Comminuted tetrapod fracture) - comminuted tetrapod fractures are an absolute indication for ORIF (after excluding an orbital injury). Treatment is similar to a type B fracture, with ORIF of the ZM buttress, IOR, zygomaticofrontal suture, and zygomaticotemporal suture.

Orbital floor exploration and repair

Indications for the repair of the orbital floor are controversial. Generally, if greater than 50% of the floor is involved or the defect is 1 to 2 cm^2 or larger, the orbital floor should be repaired. Additional indications include a non-resolving oculocardiac reflex, primary diplopia, enophthalmos, and entrapment of extraocular muscles. Many different materials can be used, including titanium mesh, dura, temporalis fascia, and other allogeneic implants.[7] After repair, a forced duction test should be performed to ensure normal mobility of the globe.

Number of fixation points

There is no consensus as to how many fixation points are necessary when treating ZMC fractures. In general, the more comminuted or unstable a fracture is, the more fixation points will be needed to ensure a good result. A recent meta-analysis suggested that three-point fixation had less fracture instability and orbital dystopia at three months post-operatively as compared to two-point fixation, but the quality of evidence was low.[9] An intraoperative CT scan is used to visualize the articulations of the zygoma and verify adequate reduction. The zygoma and its articulations can also be palpated after fixation to determine if additional fixation points are needed.

Order of plating

There is no universal order of plating in multipoint fixation. In single-point fixation, the ZM buttress usually gets plated. The zygomaticofrontal suture can also get plated, though most would argue that the intraoral incision used to plate the ZM buttress is less morbid than approaches to the ZF suture. In two-point fixation, the zygomaticofrontal suture should be plated first, followed by the ZM buttress. In three or four-point fixation, the ZF requires plating first, then the ZM buttress, then the IOR followed by the zygomatic arch if necessary. If one plans to plate the zygomatic arch from the outset, it can often be plated first to ensure adequate projection of the ZMC. If concomitant repair of the orbital floor is necessary, it should take place after the zygoma has had a reduction performed.

Soft tissue suspension

If the lateral canthal tendon has suffered disruption, it requires resuspension with suturing to the tubercle of Whitnall. The malar eminence can be suspended to prevent ectropion or scleral show.

Summary of Surgical Approaches

- If possible, existing lacerations are utilized to approach fixation sites.

- Zygomaticofrontal suture

- Lateral brow incision

- Upper blepharoplasty incision

- A transconjunctival incision with lateral canthotomy

- Coronal incision

- ZM suture

- intraoral incision

- IOR and orbital floor

- Subciliary or subtarsal incision

- Transconjunctival incision

- Zygomatic Arch

- Percutaneous stab incision for placement of Caroll-Girard screw - requires a conspicuous scar and theoretically puts the facial nerve at risk

- Temporal incision (Gillies) - conceals the scar in the hairline; NOTE: the facial nerve can be preserved by staying deep to the temporalis fascia (e.g., the superficial layer of deep temporal fascia) during dissection

- Intraoral incision (Sheen) - conceals the scar in the mouth and avoids facial nerve injury; NOTE: a careful, watertight closure of the intraoral incision can prevent plate exposure in the mouth and oroantral fistula formation to the maxillary sinus

- Coronal or hemicoronal incision

Timing of repair

Fracture repair should take place as quickly as possible before scarring, and healing of bony fragments begins. Because significant facial edema guises aesthetic deformities and increases exposure difficulty, fracture repair should ideally take place within 7 to 10 days of the initial injury. Fracture repair from 2 to-6 weeks post-injury is possible, but usually more difficult due to ensuing fibrosis and scarring. Fracture repair past six weeks is extremely challenging, but the surgeon can facilitate it by the use of intraoperative imaging and navigation. If orbital floor repair is necessary, it should ideally occur within two weeks of the injury.[7]

Differential Diagnosis

As stated above, the zygoma comprises a significant portion of the inferior and lateral orbital walls; thus, any fracture of the zygoma warrant investigation into fractures or injury of the orbit. Also, cervical spine injury must be ruled out, as well as other concomitant facial fractures, including frontal sinus, nasal, midface (e.g., Lefort, NOE), and mandible fractures. Septal hematoma should be ruled out as well to avoid septal necrosis and resultant saddle nose deformity. Lastly, malocclusion requires attention, as well.

Prognosis

Comminuted fractures of the ZMC have worse outcomes than non-comminuted fractures and have a higher rate of reoperation.[10] Estimates are that up to 5% of patients will require a second operation within four weeks due to inadequate fracture reduction.[11] Patients may have persistent paresthesia, enophthalmos, diplopia, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction.[10][12] Research estimates that some degree postoperative asymmetry occurs in 20 to 40% of patients, with major asymmetry occurring in 3 to 4% of patients. Permanent paresthesia occurs in 22 to 65% of patients.[13]

Complications

Complications from ZMC fractures can be related to the initial injury itself or operative management.[14]

- Pain

- Facial asymmetry

- Scarring

- Bleeding (epistaxis)

- Hardware failure (exposure, palpability))

- Infraorbital nerve paresthesia

- Temperature sensitivity

- Facial paresis or paralysis

- Poor cosmetic result

- Trismus

Orbital complication (usually related to clinically significant concomitant orbital floor fracture):

- Blindness

- Decreased visual acuity

- Ectropion/entropion/lid malposition

- Corneal exposure/abrasion

- Ptosis

- Epiphora

- Enophthalmos/orbital dystopia

- Diplopia

- Superior orbital fissure syndrome

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative care and recovery vary depending on the degree of injury and subsequent repair methods involved. Regardless, the patient should be advised to refrain from strenuous activity for at least two weeks to allow for complete healing with minimal bruising and swelling. Depending on the fractures involved, ancillary care postoperatively may include lubricating eye drops (orbital fractures), nasal irrigations (communication with the sinonasal contents), oral rinses (intraoral incisions used), or soft diet (mandible fractures/malocclusion). Incision lines require antibiotic ointment application (must be an ophthalmic ointment for periorbital incisions) for at least 72 hours postoperatively and then transitioned to petroleum ointment thereafter until the incisions heal completely. Avoidance of sun exposure and/or proper sun protection, as well as the use of silicone-based scar creams/ointments, may help improve the appearance of any scars. The patient should be followed closely postoperatively for any potential complications, namely related to infection and/or visual complaints. Visits usually occur at one-week post-operatively and then a few weeks thereafter up until the fractures appear stable and any complications are ruled out.

Consultations

As stated previously, a full trauma workup should be administered to rule out any concomitant injuries to determine the most appropriate consultations (e.g., neurosurgery, ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery, otolaryngology, oral-maxillofacial surgery, vascular surgery, etc.).

NOTE: Ocular injuries occur in 20 to 60% of ZMC fractures. There should be a very low threshold for ophthalmology consultation if an orbital injury is suspected.

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is important to thoroughly counsel patients regarding the potential acute and long term complications of surgery so that they can make an informed treatment decision.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Existing evidence regarding management of ZMC fractures is relatively low quality resulting in variation in management patterns; however, attention to form and function remains crucial when evaluating and repairing such fractures.

- Treatment options of ZMC fractures include observation, closed reduction, and ORIF depending on the severity of the fractures.

- Use the least number of incisions and fixation points as possible to achieve a stable reduction and fixation.

- There should be a low threshold for consulting ophthalmology to rule out orbital injury.

- There is no compelling evidence for routine antibiotic use when treating zygomatic fractures.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Successful management of zygomatic arch and ZMC fractures requires coordination between the surgical team (otolaryngology, plastic surgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery), ophthalmology, anesthesiology, trauma surgery, and perioperative nursing, operating as a cohesive, interprofessional team. A careful preoperative evaluation is paramount. It is essential to identify and document concomitant injuries to ensure that the most pressing issues get addressed first — any ocular injury requires attention before fracture management. Comorbidities require consideration when deciding on operative versus conservative management. Postoperatively, the specialty trained nursing staff should carefully monitor visual acuity and extraocular movements. The patient should understand that paresthesia of the infraorbital nerve and trismus are not uncommon and may persist. The surgical team and nursing staff should caution the patient to abstain from heavy lifting and strenuous activity for at least two weeks after surgery. This interprofessional team approach is the best means by which to attain positive patient outcomes with minimal adverse events. [Level 5]

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)