EMS Pneumothorax Identification Without Ancillary Testing

- Article Author:

- Matthew Talbott

- Article Author:

- Abraham Campos

- Article Author:

- Onyinyechukwu Okorji

- Article Editor:

- Thomas Martel

- Updated:

- 8/30/2020 8:36:58 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- EMS Pneumothorax Identification Without Ancillary Testing CME

- PubMed Link:

- EMS Pneumothorax Identification Without Ancillary Testing

Introduction

Pneumothorax is a principal diagnosis for emergency medical services (EMS) providers to identify, which is a potentially life-threatening condition. It is commonly associated with complaints such as chest pain, shortness of breath, and trauma. The condition spans all age groups, and EMS providers should, therefore, maintain a high index of suspicion for pneumothorax for any patient with a sudden onset of acute respiratory distress and ipsilateral chest pain.

Pneumothorax is the entry of air into the potential space between the parietal and visceral pleura. Air can enter the chest cavity from a disrpution in the lung tissue or trauma to the pleura. Lung tissue can spontaneously rupture in patients with risk factors such as tobacco use, Marfan’s syndrome, underwater diving, airplane travel, and male gender. It can also occur secondarily as a part of a chronic lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), interstitial lung disease, or pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) due to the destruction of lung tissue.[1] EMS providers may also encounter several different mechanisms of injury that violate the pleura creating a pneumothorax, such as penetrating trauma to the chest or blunt trauma with a rib fracture. EMS providers may be called to the outpatient setting where medical procedures involving the chest or neck may cause an iatrogenic pneumothorax, such as central venous catheter placement, thoracentesis, and lung biopsies.

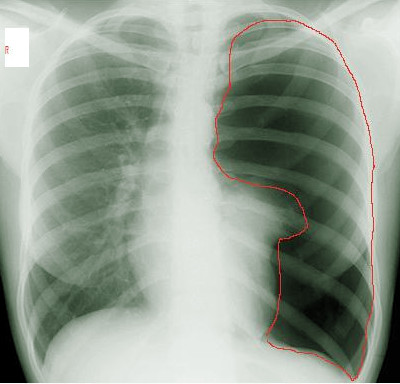

EMS providers are challenged in making the diagnosis for several reasons. They do not have access to emergency department diagnostic equipment such as chest radiographs and point of care thoracic ultrasound which may clinch the diagnosis. Many patients will have comorbid conditions that may mimic a pneumothorax including COPD/asthma, congestive heart failure (CHF), and pleural effusions, which may cause decreased breath sounds during acute exacerbations and acute dyspnea. A hemothorax will have a similar presentation as a pneumothorax, with symptoms such as dyspnea, hypoxia, decreased breath sounds, and chest pain. A key clinical finding that separates these two is that a pneumothorax will have hyper-resonance to percussion, but a hemothorax will have a hypo-resonance to percussion. Definitive treatment of both conditions may require a chest tube depending on the level of severity, but only a tension pneumothorax will require needle decompression.

Ambient noise in the field may drown out differences in lateralized breath sounds. Low light, body fluid, and other environmental factors may make otherwise obvious chest wall openings unapparent in emergencies. In the appropriate clinical setting of acute dyspnea, but equivocal breath sounds, EMS providers may percuss the thorax for unilateral hyper-resonance and asymmetric tactile fremitus in making the diagnosis.

Anatomy and Physiology

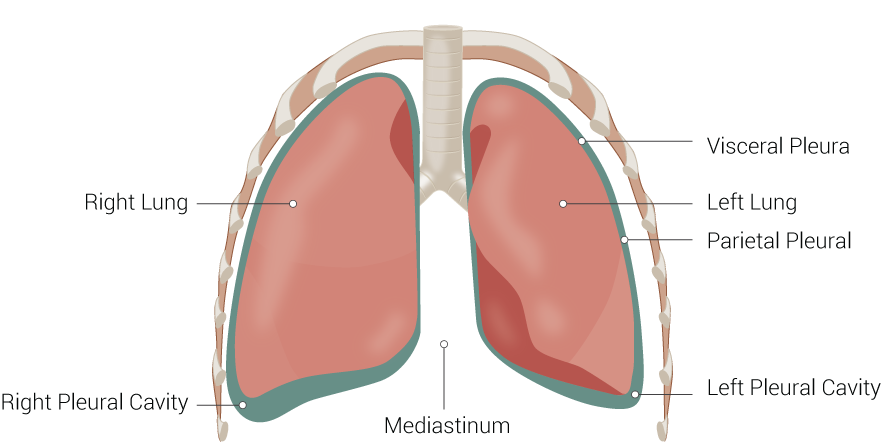

The pleura is an impermeable membrane that surrounds the lungs and is a barrier between the lungs and the chest wall. It divides the pleura into two parts. The innermost layer, the layer directly in contact with the lung parenchyma, is called the visceral pleura. The layer between the visceral pleura and the chest wall is the parietal pleura. A pneumothorax develops when air enters the potential space between the two layers of pleura.

Indications

Patients with pneumothorax typically present with acute onset of shortness of breath and unilateral pleuritic chest pain. The most common abnormal vital sign is tachycardia, but tachypnea and hypoxia may also be present in moderate to severe cases. Unilateral decreased breath sounds are the most common physical finding, but EMS providers may notice significant dyspnea, unilateral chest rise, and jugular venous distension in the most severe cases.

A pneumothorax may develop tension if the one-way entry of air causes enough intrathoracic positive pressure to accumulate, leading to decreased cardiac output and displacement of the heart and great vessels. The clinical features of tension pneumothorax include the previously mentioned characteristics plus signs of hypotension, hypoperfusion, neck vein distension, and tracheal deviation (in the latest stage of the disease). This usually occurs when the intrathoracic pressure is greater than 15 to 20 mm Hg.

Technique

Once the diagnosis of pneumothorax is suspected, airway, breathing, and circulation should be secured according to standard EMS protocol. Emphasis should be focused on placing the patient on high-flow oxygen, as it relieves hypoxia and decreases the size of the pneumothorax. Through the administration of high-flow oxygen, a nitrogen gas pressure gradient helps to reabsorb some of the intrapleural air.[2][3][4]

If the patient is hypotensive or showing signs of hypoperfusion, then providers should initiate temporizing treatment for tension pneumothorax. Open chest wounds should have a sealable dressing placed over them with a one-way air valve to prevent air build up. This one-way valve can be created by applying an occlusive dressing and taping on three sides. The EMS provider should perform needle decompression on the chest wall to release encased air. Also, patients presenting with cardiac arrest or pulseless electrical activity with suspected pneumothorax should be needle decompressed by the emergency provider. Needle decompression should be performed in the second or third intercostal space, just superior to the rib in the midaxillary line using a 14 gauge needle in adults or an 18-gauge needle in children. Also, needle decompression can be attempted in the fourth or fifth intercostal space in the anterior axillary line. The location of the intercostal blood supply is located just inferior to each rib, so this area should be avoided. Inserting a needle medial to the midclavicular line increases the chances of injuring the mediastinal vessels.[5]

Complications

After attempted decompression, reassess the patient by auscultating lung sounds. This is only temporizing treatment. A patient with a tension pneumothorax will need a chest tube placement upon arrival to the emergency department. Complications of treatment include worsening pneumothorax, bleeding, infection, and lung parenchymal damage.

Three to six hours of observation is recommended for those patients that have a simple, spontaneous pneumothorax that was treated only with oxygen and observation. Any other patient should be observed for longer periods. Following a pneumothorax, there is an increased risk of recurrence, especially at high altitude altitudes, so patients should avoid traveling by air for 7 to 14 days after treatment. Additionally, the patient should not go diving unless they have been managed with definitive surgical treatment.[4][6]

Clinical Significance

Pneumothorax is the accumulation of air in a potential space between the parietal pleura and visceral pleura. Signs and symptoms of a simple pneumothorax include acute onset chest pain, dyspnea, hypoxia, tachycardia, decreased unilateral breath sounds, and hyper-resonance to percussion. The simple pneumothorax can evolve into a tension pneumothorax with similar symptoms plus signs of hypotension, hypoperfusion, jugular venous distention, and contralateral tracheal deviation. If an EMS provider suspects a tension pneumothorax, they should perform immediate needle decompression in the second intercostal space to restore cardiac output. The definitive treatment for pneumothorax is chest tube placement in the emergency department.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Optimal clinical outcomes occur when each healthcare provider acts an interprofessional team player. This includes EMS personnel, technicians, nurses, and doctors. Each person can help monitor a patient who presents with signs and symptoms of an evolving pneumothorax, especially if pneumothorax is not diagnosed on initial presentation. The patient may need a needle decompression or a chest tube placed who may not have needed it before. Good communication between team members is key to providing the best patient care possible.[7][8]