Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Anterolateral Abdominal Wall

- Article Author:

- Kevin Seeras

- Article Author:

- Ryan Qasawa

- Article Author:

- Ricky Ju

- Article Editor:

- Shivana Prakash

- Updated:

- 7/27/2020 12:46:13 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Anterolateral Abdominal Wall CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Anterolateral Abdominal Wall

Introduction

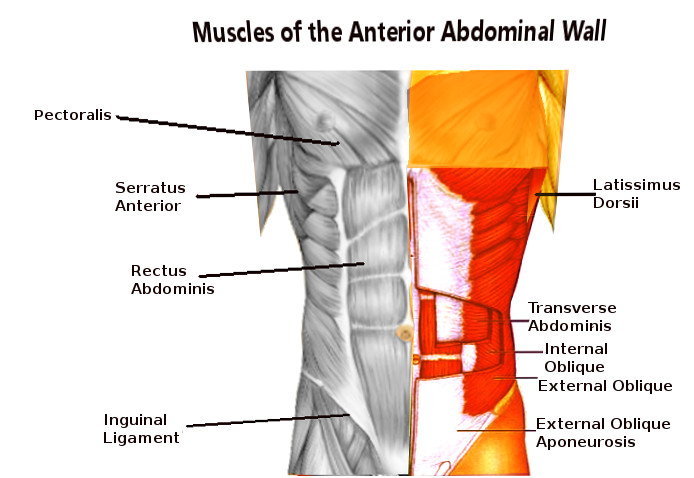

The abdominal wall is a complex organ with many functions that contribute to a patient's quality of life. The anatomical core of the anterolateral abdominal wall is mainly comprised of 4 paired symmetrical muscles. Classically the anterolateral abdominal wall has been described as separate layers from superficial to deep as follows:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous tissues (further divided into the more superficial Camper’s fascia and the deeper Scarpa’s fascia)

- External oblique muscle

- Internal oblique muscle

- Transversus abdominis muscle

- Transversalis fascia

- Parietal peritoneum

Each component has its unique contribution to the abdominal wall and will be further described in this review.

Structure and Function

The main functions of the anterolateral abdominal muscles include the stabilization of the vertebral column, movement of the trunk, and the tensioning of the abdominal wall. The function of the anterolateral wall as a whole includes protection of the abdominal viscera, maintenance of the anatomical position, assistance in forceful expiration, and involvement in any activity which serves to increase intra-abdominal pressure.

Embryology

Embryonic differentiation is based on 3 layers: the outermost protective layer termed the ectoderm, the middle mesoderm, and the innermost layer termed the endoderm. The mesoderm is further divided into 2 layers: the splanchnic, which forms the abdominal viscera, and the somatic, which develops into the abdominal wall.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial Supply

The arterial supply to the abdominal wall is derived from the following:

Six Most Inferior Intercostal Arteries and Lumbar Arteries

- Courses from lateral to medial in-between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles along with the intercostal, iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. The branches pierce the lateral border of the rectus sheath and freely communicate with the epigastric arteries.

Superior Epigastric Arteries

- A terminal branch of the internal mammary, also known as the internal thoracic, artery bilaterally. Descends within the rectus sheath (posterior to the rectus muscle but anterior to the posterior rectus sheath) to form an anastomosis with the inferior epigastric artery.

Inferior Epigastric Arteries

- A branch of the external iliac artery just before it crosses the inguinal ligament. It courses superiorly in the pre-peritoneal space (space between the transversalis fascia and parietal peritoneum) to meet the superior epigastric vessels.

Deep Circumflex Iliac Arteries

- Arises from the external iliac artery laterally just distal to the inferior epigastric artery branching; contributes blood to the abdominal wall via an ascending branch

Venous Drainage

The venous drainage of the abdominal wall superior to the umbilicus is via the internal mammary, intercostal and long thoracic veins. These veins ultimately drain into the superior vena cava (SVC). Inferior to the umbilicus, the venous drainage is via the superficial epigastric, circumflex iliac and pudendal veins. These will drain to the groin in the saphenofemoral junction and ultimately reach the inferior vena cava (IVC). An important embryological consideration of the venous drainage is the ligamentum teres. This contains the remnant of the umbilical vein which is a connection of the abdominal wall veins and the left portal vein branch. In the setting of portal hypertension, this vein may recanalize and lead to dilation of the abdominal wall veins (caput medusae).

Lymphatic Drainage

The lymphatic drainage of the abdominal wall parallels the venous drainage. The abdominal wall lymphatics superior to the umbilicus will drain to the axillary lymph nodal basin, and those inferior to the umbilicus will drain to the inguinal lymph nodal basin. Again, the embryological origin of the ligamentum teres allows gastrointestinal cancers to metastasize to the periumbilical abdominal wall termed “Sister Mary Joseph nodules.”

Nerves

The sensory and motor innervations to the abdominal wall are primarily derived from the anterior rami of T7 through T12. These course in an inferior and medial direction between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles. The anterior ramus of T12 along with the first lumbar nerve contribute to the common trunk of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. The ilioinguinal nerve is found within the inguinal canal and provides sensation to the ipsilateral medial thigh and scrotum. The iliohypogastric nerves provide sensation to the anterior abdominal wall in the supra-pubic region.

Muscles

Layers of the Anterolateral Abdominal Wall

Subcutaneous Tissues

Camper’s fascia can be thought as the superficial subcutaneous fat; there is not much collagen in this layer and thus not a strength layer. Scarpa’s fascia is contiguous with the tensor fascia lata of the thigh. It is deeper to the fatty layer and contains more collagen; many surgeons approximate this layer with abdominal wall closures.

External Oblique

This is the most superficial, largest, and thickest of the 3 anterolateral abdominal wall muscles. It originates from the lower 7 ribs and runs obliquely from superior/lateral to inferior/medial (hands in pocket orientation) to insert on the anterior one-half of the iliac crest. The most inferior extension folds posteriorly and superiorly to for the inguinal ligament. At the mid-clavicular line, the muscle belly ends, but the aponeurosis extends medially to the linea alba, contributing to the anterior rectus sheath.

Internal Oblique

This is the middle layer of the 3 anterolateral abdominal wall muscles originating from the iliopsoas fascia, lateral iliac crest, and lumbodorsal fascia. Its fibers course opposite to the external oblique from inferior/lateral to superior/medial to insert on the cartilage of the lower 5 ribs. Inferiorly, it will take a more transverse course and insert onto the pubic tubercle. At this inferior portion, it will join the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle to create the conjoined tendon. Like the external oblique, this muscle gives off a medial extension of the aponeurosis to contribute to the rectus sheath. Above the semicircular line of Douglas (approximately just below the level of the umbilicus) the internal oblique aponeurosis splits around the rectus abdominis muscle to give contributions to the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths. Below this line, the aponeurosis just contributes to the anterior rectus sheath. Inferiorly this muscle will give off fibers that encircle the spermatic cord termed the cremasteric fibers.

Transversus Abdominis

This is thinnest and deepest of the 3 anterolateral abdominal wall muscles. It originates from the lower 6 costal cartilages, lumbar vertebrae, iliac crests, and iliopsoas fascia. The fibers are oriented transversely and contribute to the rectus sheath medially. Above the semicircular line of Douglas, it courses posterior to the rectus muscles to contribute to the posterior rectus sheath. Inferiorly the aponeurosis contributes only to the anterior rectus sheath.

Transversalis Fascia

The endoabdominal fascia lines the entire abdominal cavity. It has specific names which are based on anatomic locations and include the diaphragmatic fascia, obturator fascia, iliopsoas fascia, among others. The transversalis fascia is just deep to the transversus abdominis and posterior rectus sheaths. This is an important layer as its violation defines an abdominal wall hernia.

Parietal Peritoneum

This is a thin layer of connective tissue deep to the transversalis fascia. On its deep surface is a single cell layer of squamous mesothelium.[1]

Physiologic Variants

There are many anatomical variations in the literature.[2] “Classic” anatomy is described in just over 50% of observes specimens. Common variations include different sensory distribution of nerves, presence or absence of accessory internal oblique or pyramidalis muscles, and different composition of the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths.

Embryologic malformations may result in ventral abdominal wall defects at birth. These include ectopia cordis, bladder exstrophy, omphalocele, and gastroschisis. [3]

Surgical Considerations

Intricate knowledge of the abdominal wall is necessary when performing abdominal wall reconstruction. Techniques such as component separations require meticulous dissection of the different abdominal wall layers as well as the preservation of blood supply. It is also important to avoid injury to the innervation of the abdominal wall as this can contribute to loss of function and abdominal wall weakness. [4],[5]

Clinical Significance

The knowledge of the abdominal wall innervation and its anatomic location is important when considering postoperative analgesia. There are many techniques employed to deliver local anesthetic to the nerves of the abdominal wall in hopes of superior analgesia after abdominopelvic surgery. A popular example is termed the transversus abdominis plane block (TAPS block).[6] This proven technique involves the administration of a local anesthetic to the sensory innervation of the abdominal wall situated in a plane between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles. There are typically 2 techniques used; one involves ultrasound guidance, and the other is via direct visualization. Both methods have yielded statistically significant results when considering postoperative pain control.

Other Issues

As we expand our knowledge of the abdominal wall, we can expect new techniques for abdominal wall reconstruction and postoperative analgesia. Every clinician, particularly surgeons, should have a thorough understanding of this complex anatomy.