Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Pelvis Bones

- Article Author:

- Christian Figueroa

- Article Editor:

- Patrick Le

- Updated:

- 9/16/2020 4:25:29 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Pelvis Bones CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Pelvis Bones

Introduction

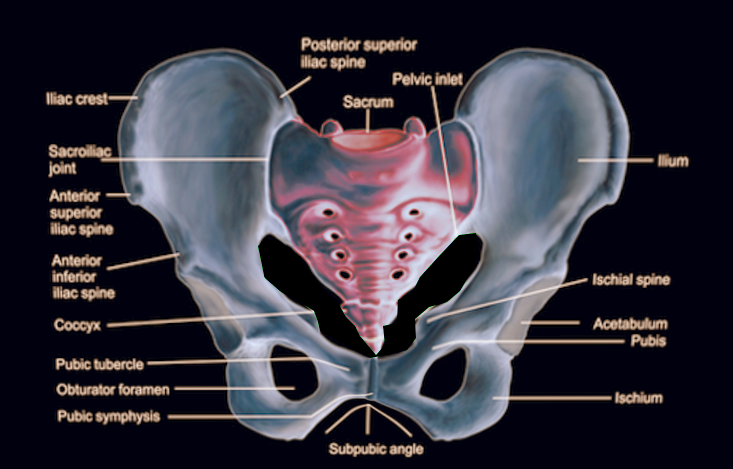

The pelvis consists of the right and left hip bones (coxal or pelvic bones) joined with the sacrum. Anteriorly the hip bones meet to form the pubic symphysis. Posteriorly the hip bones unite with the sacrum to form the sacroiliac joints. Together, this structure forms a basin-shaped ring called the bony pelvis or pelvic girdle that functions as the connection between the axial and the appendicular skeleton.

Each hip bone consists of three bones: the ischium, ilium, and pubis. The Ilium is the physically largest of the three pelvic bones. It is located superiorly relative to the pubis and ischium. It is composed of a wing-shaped portion called the superior ala along with the inferior body. The rim of the superior ala is called the iliac crest. Anteriorly this crest ends at the anterior superior iliac spine and posteriorly at the posterior superior iliac spine. Inferior to these ends will be their inferior equivalents.[1]

The ischium is the inferior posterior portion of the hip bone. It consists of a superior body and an inferior ramus. At the junction posteromedial, the bone has a projection called the ischial spine. The concavity between this spine and the posterior inferior iliac spine from the greater sciatic notch. The concavity between this spine and inferior ramus is called the lesser sciatic notch.

The pubis is the inferior, anterior portion of the hip bone. It consists of a superior ramus, body, and inferior ramus. The superior ramus helps form the acetabulum. The inferior ramus of the pubis fuses with the inferior ramus of the ischium. The pubis and ischium together form the obturator foramen. The body of both the left and right pubis join to form the pubic symphysis joint.

The sacrum forms from the fusion of the five sacral vertebral bodies. On each side, it forms the sacroiliac joints along with the iliac bone.

Structure and Function

The functions of the pelvic bones are locomotion, childbirth, and support to the abdominal viscera. It serves to transmit the weight from the axial to the lower appendicular skeleton. Likewise, the pelvis bears the weight of the upper body when sitting. The bony structure also provides attachment sites for many muscles of the abdomen, pelvis, and lower extremity. It also provides attachment sites for external reproductive organs. Additionally, the pelvic girdle serves to protect the pelvic and abdominopelvic viscera.[2]

Embryology

The formation of the pelvic bones involves a fusion of multiple elements that allows articulation of the axial skeleton with the lower extremities. In early life, the bones of the hip (ilium, ischium, and pubis) remain separate but attach to each other via the triradiate cartilage. Upon puberty, these bones fuse to form the acetabulum, a socket on the lateral aspect of the hip in which the femoral head articulates.

The lateral plate mesoderm forms the ilium, ischium, and the pubis. These bones then undergo endochondral ossification similar to long bones but an initial blastemal structure forms which then undergoes chondrification. Afterward, sites of primary ossification centers form.[3]

The sacrum undergoes this type of ossification as well.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Vascular supply to the bones of the hip comes from branches of both the external and internal iliac arteries. Both of these come from the bifurcation of the common iliac artery which bifurcates at the level of L5-S1 vertebral level. The external iliac artery travels along the pelvic brim and gives off the inferior epigastric artery and the deep circumflex iliac artery. It then transitions into the femoral artery after passing the inguinal ligament. The internal iliac artery travels posteromedial into the pelvis, which it then bifurcates into the anterior and posterior divisions of the internal iliac artery. The anterior division includes the umbilical, obturator, inferior vesical, uterine, vaginal, middle rectal, internal pudendal, and the inferior gluteal. The posterior division consists of the iliolumbar, lateral sacral, and the superior gluteal arteries.[4]

The sacrum receives blood supply from the lateral sacral and the median sacral arteries. The lateral sacral arteries are a branch of the internal iliac artery. The median artery is a branch from the aorta after its bifurcation into the internal and external iliac arteries.

The lymphatic system of the pelvis has many contributions and groups of lymph nodes. The main groups of lymph nodes are the external iliac lymph nodes, internal iliac lymph nodes, sacral lymph nodes, and the common iliac lymph nodes.

Nerves

Innervation of the pelvis includes mainly the sacral and coccygeal plexuses.

The sacral plexus derives from the L4-S4 nerve roots, and it sits on the internal surface of the piriformis muscle. Most of the sacral nerves stemming from the sacral plexus exit through the greater sciatic notch. The sciatic nerve forms out of the sacral plexus and can be compressed by the muscle, causing radicular pain down the leg. This form of entrapment neuropathy by the compression from the piriformis muscle is called piriformis muscle syndrome.[5][6]

The coccygeal plexus forms from the S4-S5 nerve roots, and it lies along the coccygeus muscle on the pelvic surface.

The autonomic system also provides innervation to the pelvis, which mainly courses via the inferior hypogastric plexus. This plexus is made up of the nerve fibers from the sympathetic splanchnic nerves, parasympathetic splanchnic nerves, and hypogastric nerves. The autonomic nerves are travel to the organs via their corresponding splanchnic nerve group.

Muscles

The pelvic bones serve as an attachment for many different muscle groups involving the abdomen, pelvis, perineum, and the lower extremities. The muscles limited to the pelvis include the muscles of the pelvic wall and the pelvic diaphragm.

Along the anterolateral wall of the true pelvis lies the obturator internus muscle. This muscle extends from the bony surfaces of the pelvis into the lesser sciatic foramen and also inserts on the greater trochanter. The muscle receives innervation from the nerve to obturator internus (L5-S2). It serves as an external rotator of the hip and strengthens the hip joint.

Along the posterolateral surface of the true pelvis lies the piriformis muscle. This muscle extends from the bony surfaces of the sacrum and pelvis into the greater sciatic foramen, with its insertion on the greater trochanter of the femur. The muscle receives innervation from the anterior rami of S1 and S2. It also serves as an external rotator of the hip and strengthening the hip joint.[7]

The pelvic diaphragm consists of the coccygeus muscles and the levator ani muscles.

The coccygeus muscle is the most posterior and superior of the pelvic diaphragm muscles. It extends from the ischial spines to attach to the lateral surface of the coccyx and inferior sacral segment. Its innervation comes from branches of S4 and S5 spinal nerves. It serves as the support for the pelvic viscera and flexes the coccyx.

The levator ani can subdivide into different muscle groups (pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus) but margins are ill-defined. These muscle groups extend from the anterior bony surfaces of the pelvis to attach to the perineal body, anococcygeal ligament, and walls of viscera near the pelvic floor. The muscles are innervated nerve to levator ani, inferior anal nerve, and coccygeal plexus. They serve as support for the pelvic viscera.[8]

Physiologic Variants

Physiologic variants of the bony pelvis exist between males and females. The male pelvis is typically thicker and heavier in comparison to the lighter and thinner pelvis of the female. Males also tend to have a narrower pelvic opening than females.

Most physiological differences lie in variations of the pelvic girdle. There are four types described.

The gynecoid pelvis displays an oval shape with a wide transverse diameter. This variant is the most common type and provides adequate cavity space for a female to give birth.

The android displays a heart-shaped inlet and is most common in males.

The platypelloid displays a wide inlet transversely but short in anterior-posterior axis. This type provides challenges for a female to give birth.

The anthropoid displays an inlet wide anterior-posterior axis but short in the transverse axis.[9]

Surgical Considerations

The diameter of the pelvic ring is a surgical consideration that an OB/GYN must take into account when planning their patient's birth. The capability of vaginally delivering a baby is limited to the anatomical structure of the woman’s pelvis. This anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic inlet must be assessed radiographical or with pelvic examination. A diagonal conjugate is measured instead during the pelvic examination due to the inability to measure a true anteroposterior diameter. The distance between the ischial spines is also a consideration due to this space being the narrowest part of the pelvic canal. A cesarean section will be ab option if the anatomical structure makes vaginal birth difficult.[9]

Clinical Significance

Fractures of the pelvis are not common but when occur often involve multiple bones of the pelvis or may include the hip joint. Most pelvic fractures occur due to direct trauma (ex. car accident) or a fall from significant heights. People with existing osteoporosis are more prone to fractures of the pelvis.

The severity of the fracture determines the need for surgery. If the pelvis is fractured in multiple places and is considered unstable, then intervention may be deemed necessary. Certain types of fractures may be life-threatening.[10]

Open book fractures when the two pubic bones are separated, and the pelvis is now anteriorly open. This situation can be life-threatening due to the exposed vessels and viscera of the pelvis.

Vertical shear fractures occur when the fracture allows half of the pelvis to shift upwards. This condition can be dangerous due to significant blood loss.

Lateral crush fractures when half the fracture is displaced inwards can also represent life-threatening situations involving damage to the vessels and viscera.