Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Pelvic Joints

- Article Author:

- Michael Fisher

- Article Editor:

- Bruno Bordoni

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 11:35:23 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Pelvic Joints CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Pelvic Joints

Introduction

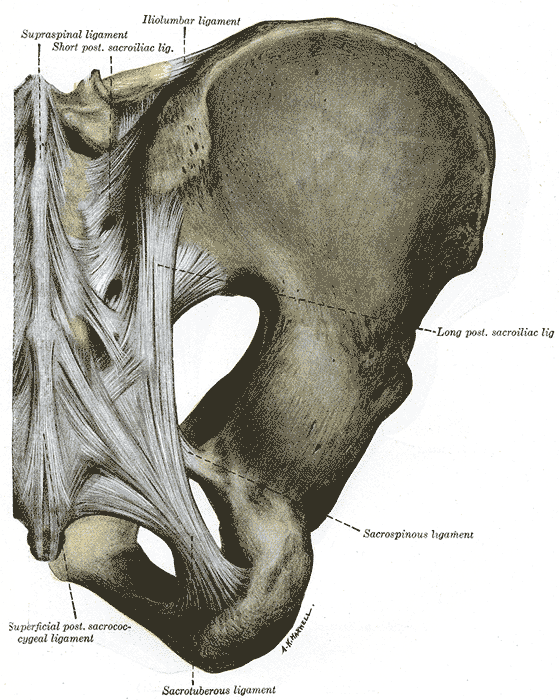

The joints of the pelvis include the sacrococcygeal, lumbosacral, pubic symphysis, and the sacroiliac. The pelvic joints are also held together by various ligaments which include the sacrotuberous, sacrospinous, and iliolumbar. The lumbosacral joint forms from the fifth lumbar vertebrae and the sacrum. In between the articular processes, this joint has an intervertebral disc. The sacrococcygeal joint is a fusion of the bone between the sacrum and coccyx. It also consists of an intervertebral disc between the two vertebrae and several accessory ligaments. The sacroiliac joint is a synovial articulation between the surfaces of the ilium and sacrum on either side. Because of the articulation, the surface of the joint is smooth and flat. The sacroiliac joint has posterior strengthening by dorsal sacroiliac and inter-osseous ligaments. When a person is upright, the body weight usually transmits to the sacrum and ilia. While sitting or supine, the person's weight transmits to the ischial tuberosity. The pubic symphysis is a cartilaginous joint located between the main body of the pubic bone in the midline. The symphysis of the pubic bone is covered with hyaline cartilage and may have a cleft. The ligaments around the pubic symphysis are flexible and relax during pregnancy.

Structure and Function

The lumbosacral junction is another critically important joint. It lays between the L5 and auricular surfaces of the sacrum with similar characteristics as lumbar vertebral joints. The vertebral bodies contain a large intervertebral disc similar to other vertebral bodies; however, the zygapophyseal joints are wider than those above. The lumbosacral joint transmits the weight of the body through the sacrum and ilium unto the femur on standing and ischial tuberosities when seated. The sacroiliac and iliolumbar ligaments strengthen the joint. The iliolumbar ligament, in particular, is the most important in restricting lumbosacral joint motion.

The pelvic girdle is composed of three bones on either side known as the ilium, ischium, and pubis which attach to the sacrum and femurs to connect the axial and appendicular skeletons. The pelvic girdle has several attachments, starting with the sacrum and ilium. The ilium attaches to the sacrum via ligaments known as sacroiliac ligaments at the most dorsal areas. These ligaments are just part of what holds the sacroiliac joint. Additionally, the sacrum and ilium have matching irregular contours that which increase joint strength and stability. Each hemipelvis meets at the most ventral point known as the pubic symphysis. The pubic symphysis is a fibrocartilaginous joint which allows for it to be amphiarthrotic, in other words somewhat flexible. The ligaments of the pubic symphysis that strengthen the joint are superior pubic ligament; inferior pubic ligament; anterior pubic ligament; posterior pubic ligament. The flexibility at the ventral aspect allows for an increase in the function of the pelvis.

The pelvic girdle has several essential functions especially in locomotion, despite being comprised of relatively fixed joints. There are a number of muscles which originate from pelvic attachments both on the external and internal surfaces of the pelvic girdle. The muscles originating from the external pelvic girdle assist primarily with locomotion, with attachments along the femur and femoral head within the acetabulum. Additionally, these muscles are crucial for stability and proprioception. The internal surfaces of the pelvic girdle serve as attachments for muscles what is known as the pelvic “floor.” The pelvic floor muscles serve several functions. First, they function to contain the visceral organs by serving as structural integrity and prevent prolapse through the pelvic outlet. A second function of the pelvic floor is control of the anal sphincter, the urinary outlet and the vagina in females.

Of note, the structure of the pelvis in both size and shape differs between males and females. Female patients are observed to have a larger width of the pelvic inlet and outlet, which is evidently a product of evolution. Additionally, the ilia differ between males and females, so much that the height of the ilia has become a significant measure for sex determination in recovered skeletons.[1]

Embryology

Morphology of the skeletal system occurs in the following order, primordial mesenchyme to chondrification to primary ossification to secondary ossification. Primary ossification begins in utero, however, continues postnatally, with secondary ossification continuing until adulthood. The pelvis joints articulate the appendicular with the axial skeleton. The appendicular skeletal elements first appear around 28 days. The sacrum is a part of the axial skeleton, which develops from somites first emerging near the skull around 20 days, with three to four subdivisions developing each day to form the vertebral column. By about day 29, a series of five sacral somites appear followed by coccygeal somites. Chondrification of these structures begins in the sixth week forming hyaline cartilage bone models that are now discernable on radiologic studies. Chondrification centers of the ilium, ischium, and pubis, however, appear by 9 weeks gestation but develop rapidly. By the next week, primary ossification centers can be seen namely at the iliac crest. At the same time, week 10, the sacrum and ilium begin fuse forming the sacroiliac joint.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the pelvis originates from the descending aorta. The aorta bifurcates into the common iliac arteries at approximately the level of the umbilicus. The common iliac arteries bifurcate at the pelvic brim into the internal and external iliac arteries. The external iliac exits the pelvis through the inguinal ligament, where it becomes the femoral artery supplying the lower extremity. The internal iliac artery has two major divisions, the anterior and posterior which supply pelvic organs, perineum, and gluteal muscles. The anterior division further divides into several branches, the umbilical, superior and inferior vesicular, obturator, and internal pudendal. The arteries supply pelvic organs, such as the bladder, prostate/uterus, and seminal glands, as well as the pelvic floor, head of femur and ilium. The posterior division of the internal iliac includes several branches. The iliolumbar artery, lateral sacral arteries, and superior gluteal arteries combine to supply the sacroiliac joint.

The pelvis contains several groups of lymph nodes including the internal, external, and common iliac nodes. Additionally, they include the sacral, pararectal, lumbar and inguinal nodes. There is an extensive meshwork between the groups; however, the nodes trace the venous system to back to the common iliac veins and further up to drain into the cisterna chyli before traversing the thoracic duct. The extensive communication facilitates the spread of cancer amongst abdominal and pelvic organs.[2]

Nerves

There are four nervous supplies to the pelvis, motor, sensory, parasympathetic and sympathetic. The motor and sensory innervation arise from two plexuses, the sacral plexus and coccygeal plexus. The parasympathetic innervation arises from the sacral splanchnic nerves and the sympathetic innervation via the hypogastric plexus.

The sacral plexus arises from L4 to S4 spinal nerves and includes the longest nerve in the body, the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve is comprised of L4 to S3 nerve roots and innervates the entire skin as well as most of the muscles of the leg and foot. The sacral plexus additionally gives rise to the pudendal, superior and inferior gluteal, as well as the nerves to quadratus femoris, piriformis and obturator internus nerves. There are several cutaneous branches of the sacral plexus as well as innervating the medial and lower buttock, posterior thigh/leg and perineum. Lastly, the parasympathetic innervation of all pelvic organs arises from the pelvic splanchnic nerves which stem from S2 to S4 spinal roots.

The coccygeal plexus arises from S4, S5, and coccygeal nerves and are responsible for the innervation of the coccygeus and levator ani muscles of the pelvic floor.

The sympathetic innervation of the pelvis arises from the superior hypogastric plexus as well as inferior hypogastric plexus. However, the inferior hypogastric plexus carries both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. Parasympathetic output causes gastrointestinal peristalsis, contraction of muscles for defecation and urination, as well as erectile function. The sympathetic output is largely antagonistic to parasympathetic output in the pelvis, but it also is responsible for muscle contraction during orgasm.[2]

Muscles

This section briefly discusses the pelvic musculature. The pelvic musculature subdivides into three major categories; muscles that cross the lumbosacral joint, hip joint muscles, and muscles located wholly within the pelvis that makes up what is known as the pelvic floor.

Pelvic muscles that cross the lumbosacral joint attach the pelvis to the trunk. These muscles assist with the sacrum and lumbar spine in flexion and extension and affect lumbar spine rotation and lateral flexion. Lumbosacral flexion is performed with contraction of rectus abdominis anteriorly as well as external and internal oblique abdominal muscles. The psoas major is believed to play an accessory role in flexion as well. Extension occurs with contraction of erector spinae group which consists of the iliocostalis, longissimus, and spinalis muscles, assisted by smaller muscles known as multifidi.

Pelvic muscles that cross the hip joint are also divisible at the hip into quadrants; the hip flexors are in an anterior location, extensors posterior, adductors situated medially, and abductors laterally. These groups derive their names from their actions, i.e., the hip flexors assist with flexion; however, this may be an oversimplification as many of the muscles contribute in more than one motion. The hip flexors are the psoas major, iliacus, sartorius, pectineus and rectus femoris. The hip extensors are the gluteus maximus and hamstrings (long head of biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus). The adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, gracilis, and pectineus comprise the adductor group. The tensor fascia lata (TFL), gluteus minimus and gluteus medius are hip abductors.

Finally, we have the pelvic floor muscles which consist of three layers, the urogenital triangle, urogenital diaphragm, and the pelvic diaphragm. The pelvic floor muscles are located entirely within the pelvis and therefore do not move the pelvis. Instead, these muscles stabilize the sacroiliac joint as well as the pubic symphysis in addition to creating a stable floor for pelvic viscera. The urogenital triangle consists of the superficial transverse perineal, ischiocavernosus, bulbocavernosus and anal sphincter muscles. These muscles not only support the pelvic floor but also function in both male and female erections and defecation. The urogenital diaphragm lays deep to the urogenital triangle and stretches from the pubic symphysis to bilateral ischial tuberosities to form a triangle at the ventral portion of the pelvic outlet. Several muscles combine to make up the urogenital diaphragm, including those of the internal and external urethral sphincters. The external sphincter is skeletal muscle and regulated by voluntary control, whereas the internal sphincter is under autonomic regulation. The third and final layer of the pelvic floor is a thin, muscular layer extending from pubic rami to the coccyx and is known as the pelvic diaphragm. The pelvic diaphragm is largely composed of the levator ani muscle, which itself is comprised of three muscles: iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis. The levator ani inserts along the arcus tendinous fascia laterally and condenses in the midline to form a sling. Along the midline lays the urethra, vagina (for females) and anal canal. The pelvic diaphragm functions as the inferior most border of the internal pelvic cavity.[2]

Physiologic Variants

Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV) is an increasingly recognized anatomic variant of the lumbosacral joint associated with altered patterns of degenerative changes present in up to 35% of the general population. LSTV are considered congenital spinal anomalies along a spectrum of morphology from partial to complete L5 sacralization to partial to complete S1 lumbarization. Sacralization is where the transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra fuses to varying extents with the first segment of the sacrum with a complete sacralization showing only four existing lumbar vertebrae. Lumbarization, on the other hand, is when S1 separates from the sacrum and complete lumbarization the S1 segment is entirely separate showing what appears to be six lumbar vertebrae. Both have consequences that can be seen clinically as well as surgical considerations. In sacralization, the height of the pars interarticularis and widths of the laminae are smaller predisposing the patient to spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. In lumbarization of S1, facets are smaller and often asymmetric which predisposes for accessory joints and potentially a cause of low back pain. Additionally, researchers have observed a protective effect of transitional vertebrae discussed a possibly mimicking the situation after a fusion operation.[3]

Six variants of the sacroiliac joints have been observed: accessory joints, iliosacral complex, bipartite iliac bony plate, crescent-like iliac bony plate, semicircular defects at the sacral or iliac side and ossification centers.

Accessory sacroiliac joint: Accessory sacroiliac joint is found medial to the posterior superior iliac spine and lateral to the second sacral foramen amongst a rudimentary transverse tuberosity. On CT imaging, accessory joints have articular surfaces that resemble osseous projects from the ilium to the sacrum. An accessory joint can be present at birth; however, they more commonly result from the stress of weight-bearing. Accessory joints are more commonly present in the obese population and the older population, as well as a higher prevalence in women with 3 or more childbirths, compared to 2 or less. Patients may present with low back pain in conjunction with degenerative changes identified on radiologic imaging such as subchondral sclerosis, osteophytes, and ankyloses on articular surfaces.

Iliosacral complex: Iliosacral complex forms from a projection from the ilium articulating with a complementary sacral recess. These complexes can be unilateral or bilateral, and like accessory joints, these complexes exist at the posterior sacroiliac joint from the level of first to second sacral foramen. This variant has been seen more in older patients greater than 60 years, as well as obese women more so than normal weight women.

Bipartite iliac bony plate: Bipartite iliac bony plate is located at the posterior portion of the sacroiliac joint and appears as described, consisting of two parts and appears unilaterally.

Semicircular defects on the iliac/sacral side: The fourth variant is semicircular defects on either the sacral or iliac aspects of the articular surface of the sacroiliac joint. These can be unilateral or bilateral and again are present at the posterior portion of the sacroiliac joint from the level of the first to second sacral foramen. This defect has been observed more in women than men and in patients older than 60 years.

Crescent-like iliac bony plate: The fifth variant is a crescent-like articular surface which may be present unilaterally or bilaterally. CT imaging demonstrates a crescent-like iliac plate with accompanying bulged sacral surface. This defect is found usually at the posterior portion of the sacral iliac joint spanning the levels of the first and second sacral foramen. This defect was observed only in women and more commonly in patients greater than 60 years old.

Ossification centers of the sacral wings: The sixth anatomical variant observed is ossification centers presenting as triangular osseous bodies located within the joint space at the anterior portion of the sacroiliac joint. This defect is found at the level of the first sacral foramen, typically unilaterally.[4][5]

Surgical Considerations

Surgeons operating on the lumbosacral joint have several approach considerations to choose from and in doing so are considering goals of procedure versus risks of complications as well as contraindications to specific approaches. The various approaches to access the lumbar spine include posterior, transforaminal, minimally invasive transforaminal, lateral, oblique and anterior. Some approaches are preferable for certain lumbar fusion levels over others. Additionally, successful fusion rates associated with restoration of disc height, segmental lordosis and total lumbar lordosis vary with the approach. Risks of complications such as dural injury, blood vessel injury, or muscular injury differ as well.[6]

Surgeons operating in or around the pelvis are always aware of the numerous potential anatomical complications that may occur during surgery or the postoperative period. The surgeon must consider the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, nerves, blood vessels, and reproductive organs, particularly in females. Additionally, considerations in regards to risks of infection, hemorrhage, and thromboembolism are critical. The risk of these complications depends upon the surgical approach and co-morbidities of the individual patient.

Serious urinary tract complications may occur, and the ureters are most often involved. There are several important locations along the course of the ureter to be considered: (1) pelvic brim, (2) base of the broad ligament, and (3) ureterovesical junction. What is possibly most important to the orthopedic or trauma surgeon operating about the pelvis or its related joints is the ureter at the pelvic brim. At this is location, the ureter courses over the external iliac artery and accompanying vein approximately 1 cm lateral to the origin of the hypogastric artery. The hypogastric artery may be the single most important vessel to identify and avoid mistaking for the ureter.

Anatomical complications involving the small and large intestine or appendix are usually incidental. However, one must expect involvement of the intestines at the time due to neoplasm, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, or congenital anomalies. Often the bowel is prepared pre-operatively in anticipation of these potential complications.[7]

Clinical Significance

All the pelvic joints have the potential to develop arthritis and malignancy. One prevalent complaint by many people is a bony pain in the pelvis. This pain may be due to sacroiliitis, and the pain worsens with ambulation. The pain may also result from joint laxity and can be a referred pain (muscular, visceral, nerve entrapment). The pain of sacroiliitis is debilitating. The pain may occur in the buttocks, lower back, behind the thigh, hip, or groin. It may also correlate with paresthesias and urinary retention, frequency or urgency. Most patients are not able to find a comfortable position. Women typically report worsening of this pain during menstruation. Many people develop anxiety and depression with the disorder. The diagnosis of sacroiliitis is not easy because the pelvis contains many structures which can also present with similar symptoms. The pelvis is also rich with many large nerves which if compressed or irritated can lead to radicular pain. Neither CT scan or MRI is sensitive enough to identify disorders causing pain (especially sacroiliitis) in the pelvis. Some experts recommend a PET scan, but this imaging study is not always available and prohibitively expensive. The diagnosis of sacroiliitis means ruling out other pathologies and using clinical judgment. The treatment of the disorder is rest, NSAIDs, exercise, ice or heat, and nerve blocks. Unfortunately, most patients remain dissatisfied with treatment.

Other Issues

The sacrococcygeal joint is responsible for back pain for about 40% of all cases. The pain comes from the nociceptors connected to S1 to S3 and L4 to L5.[8]

The lumbosacral joint can be a source of pain, particularly due to the ligaments that cover it. The latter, if deformed by an alteration of the morphology and articular biomechanics can send pain signals (especially for movements such as extension and ipsilateral bending).[9]

Pubic symphysis can be a source of pain for several causes, from pregnancy to sports. The painful afference can derive, depending on the scientific texts, from the pudendal and genitofemoral nerves and/or branches of the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves.[10]

The sacroiliac joint can be a source of pain and affects about 15% to 30% of all causes of back pain. The innervation carrying this pain information is with the nerves from L4 to L5 or L5 to S4.[11][12]

(Click Image to Enlarge)