Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Bones

- Article Author:

- Mihir Patel

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 11:34:38 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Bones CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Forearm Bones

Introduction

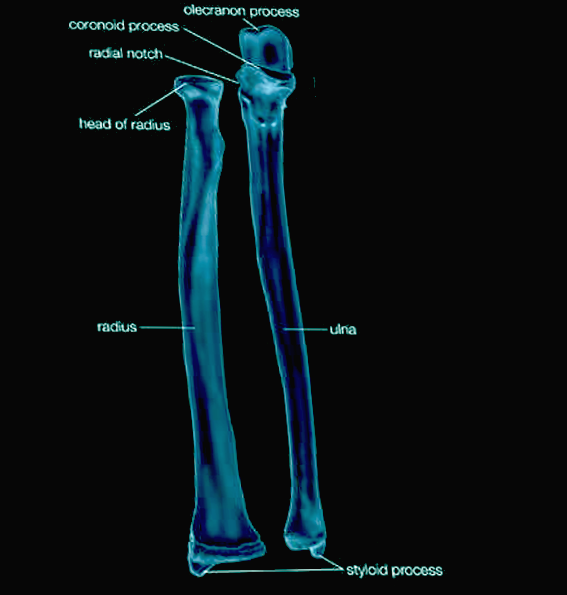

The forearm is the portion of the upper extremity extending from the elbow to the wrist. The skeletal framework for this region arises from two primary osseous structures: the radius laterally and the ulna medially. These long bones serve as origins and insertions for many muscle groups allowing for normal physiologic dynamic movements. They also provide the supportive structure needed for the passage of neurovascular bundles between the proximal and distal aspects of the upper extremity. The extent of clinical pathology involving the anatomic osseous structures of the forearm includes conditions ranging from nondisplaced and displaced fractures to osseous tumors and malignancy.[1][2][3][4]

Structure and Function

Within the forearm, the radius is positioned laterally and is the shorter of the two bones. The radial head has two points of articulation proximally: the radiocapitellar joint, articulating with the capitulum of the distal humerus and the radial notch of the ulna where it also has support from the annular ligament.[5][6] Distally, the distal radius articulates with the proximal row of the carpal bones, including the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum.[3][7] The radius has two primary bony prominences, the radial tuberosity on the medial aspect of the proximal end and the styloid process on the lateral aspect of the distal end. Each serves as a muscular insertion site as described in the sections below. Lister’s tubercle on the inferior surface of the distal dorsal radius serves as an anatomical landmark with the extensor pollicis longus tendon running around it.

The ulna is typically considered the stabilizing bone of the forearm. Proximally, the trochlear notch of the ulna articulates with the trochlea of the humerus, the olecranon articulates with the olecranon fossa of the humerus, and the radial notch articulates with the radial head. Distally, the head of the ulna articulates with the articular disk of the distal radioulnar joint with no direct contact with the carpal bones. Bony prominences of the ulna include the coronoid process and the ulnar tuberosity proximally and the styloid process of the ulna distally.[8][9]

The radius and ulna connect via the interosseous membrane of the forearm, a fibrous anatomic construct that runs obliquely between the two bones. It is comprised of 5 ligaments: the central band, accessory band, distal oblique bundle, proximal oblique cord, and dorsal oblique accessory cord. Besides the obvious physical connection, this membrane also serves to conduct forces received by the hand and radius to the ulna and subsequently the humerus. It further functions to separate the anterior and posterior compartments of the forearm.[10]

Functionally, the radius and ulna serve together as the primary support structure of the forearm articulating with the humerus and carpal bones as described above. Both bones also serve as origins and insertions for muscles that are responsible for flexion and extension of the forearm, wrist, and fingers. Additionally, because the radius can pivot around the ulna, supination, and pronation of the forearm are possible.

Embryology

In the developing embryo, the upper extremity derives from a collection of structures termed the limb bud that first appears 26 days after fertilization.[11][12] The formation of the limb bud initiates by the expression of sonic hedgehog (SHH) from the notochord. The limb bud itself is a combination of somatic mesoderm that will form muscles and neurovascular structures and lateral plate mesoderm that will form the skeletal components, including the radius and ulna. The distalmost aspect of the limb bud is termed the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) and regulates the proximodistal growth of the bud. Differentiation along the short radioulnar axis gets regulated by the zone of polarizing activity located along the ulnar aspect of the bud. Dorsoventral differentiation is under control of by non-AER ectodermal tissue. Proximal to the AER is the progress zone that sequentially differentiates into the stylopod (future arm), zeugopod (future forearm), mesopod (future wrist), and autopod (future hand).[12] Within each of these zones, cartilage precursors accumulate centrally. Both the radius and ulna develop via endochondral ossification in a proximal to distal manner. Chondrification is first seen in these bones at 36 days of fertilization with ossification starting from 6 to 8 embryonic week.[11] Ossification begins in the prenatal period centrally in the shaft of each bone and continues post-natally with the addition of proximal and distal ossification centers. All three of these regions fuse at 16 to 19 years.[13] Defects in proper development can lead to radial aplasia either as an isolated event or in addition to other congenital disabilities such as in the VACTERL association or thrombocytopenia-absent radius syndrome.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The ulnar and radial arteries comprise the primary blood supply of the forearm. They are terminal branches of the brachial artery arising at the inferior aspect of the cubital fossa.[4] The ulnar artery courses medially supplying muscles in the medial and central forearm as well as the ulnar and median nerves. Named branches of the ulnar artery include the common interosseous which subsequently gives rise to the anterior and posterior interosseous arteries. The radial artery courses laterally supplying muscles in the lateral forearm.[14]

In one study of cadaveric samples, the most common origin for the nutrient artery to the radius was the anterior interosseous artery (56%) followed by the median artery (25%). In this same study, the most common origin of the ulnar nutrient artery was the ulnar artery (40%) and the anterior interosseous artery (31%).[14] Additionally, smaller branches supplying the proximal radius originated from the radial artery while the distal radius also received penetrating vessels from the palmar arterial arches. The ulna receives small vessel input from the ulnar recurrent artery proximally and similar to the distal radius, the distal ulna received input from branches of the anastomoses between the radial artery, the ulnar artery, and the anterior interosseous artery.[15]

Classically, lymphatic vessels are thought to be absent within bone. This idea gained recent support from a study that failed to identify immunohistochemical markers of lymphatic vessels within cortical or cancellous bone.[16]

Nerves

The three primary nerves of the forearm are the median, ulnar, and radial nerves. The median and ulnar nerves travel through the anterior compartment while the radial nerve presents in the posterior, extensor compartment. The median nerve gives rise to the anterior interosseous nerve and is responsible for innervating all of the muscles of the anterior compartment other than the flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar portion of the flexor digitorum profundus which are innervated by the ulnar nerve. The radial nerve gives rise to the posterior interosseous nerve, also known as the deep branch of the radial nerve and is responsible for innervating muscles in the posterior compartment.[17][18][19][20][21][22]

Muscles

The radius and ulna serve as insertion sites for several muscles originating more proximally in the arm[23][24]:

- Biceps brachii – inserts on the radial tuberosity, a bony prominence on the medial aspect of the proximal end of the radius; allows for flexion and supination of the forearm.

- Brachialis – inserts on the coronoid process of the ulna and the ulnar tuberosity; allows for flexion of the forearm.

- Triceps and anconeus – insert on the olecranon process of the ulna allowing for the extension of the forearm.

Within the forearm, muscles are classically grouped into anterior and posterior compartments[25][26]:

Anterior Compartment:

- Flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, and the humeral heads of the pronator teres and flexor carpi ulnaris - originate from the common flexor origin. The ulnar head of the pronator teres originates from the coronoid process. The ulnar head of the flexor carpi ulnaris arises from the olecranon. The pronator teres inserts to the lateral surface of the radius and is responsible for pronation and flexion of the forearm. Each of the other muscles inserts in the wrist or hand and is responsible for more distal movements.

- Flexor digitorum superficialis - arises from the anterior border of the radius, the medial epicondyle of the humerus, and the coronoid process and inserts on the middle phalanges of the medial four digits.

- Flexor digitorum profundus - arises from the ulna and interosseous membrane and inserts on the distal phalanges.

- Flexor pollicis longus - originates from the radius and the interosseous membrane and inserts on the distal phalanx of the thumb.

- Pronator quadratus - originates from the distal end of the ulna and inserts on the distal end of the radius. Responsible for forearm pronation.

Posterior Compartment:

- Brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, and extensor carpi ulnaris - originate from the distal lateral edge of the humerus. The brachioradialis inserts just proximal to the styloid process of the radius and is responsible for flexion of the forearm, especially in pronation. The remainder of the muscles originating from this area insert distally and are responsible for movements within the wrist and hand.

- Supinator - originates from the lateral epicondyle, radial collateral and annular ligaments, supinator fossa and the crest of the ulna with insertion on the lateral side of the radius. It is responsible for forearm supination.

- Abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis longus - originates from the posterior surface of the ulna and interosseous membrane with attachments in the hand.

- Extensor indicis - originates from the posterior surface of the distal third of the ulna and the interosseous membrane with attachment in the hand.

- Extensor pollicis brevis - originates from the posterior surface of the distal third of the radius and the interosseous membrane with attachment in the hand.

Physiologic Variants

Both the radius and ulna are fundamental to the structure of the upper extremity; the literature describes no significant physiologic variants. However, pathological variants such as radial aplasia as part of the VACTERL association or thrombocytopenia with absent radii have been established and are covered above.[27]

Surgical Considerations

The surgeon can usually reach the ulna without endangering other structures because of its proximity to the skin surface. In contrast, the radius, particularly the proximal portion, is encircled by muscles. Additionally, the posterior interosseous nerve abuts the proximal radius. As such, an approach to the radius is typically more complicated. There are three primary surgical approaches to the forearm bones[25][28][29]:

- The approach to expose the shaft of the ulna is typically considered the simplest of the approaches because of the proximity of the bone to the skin. The patient is usually supine with the arm placed across the chest to best identify the ulna. Identification and preservation of the ulnar artery and nerve are key.

- The volar (Henry) approach to the radius can safely expose the entire length of the bone. The patient is typically supine with an arm board securing the arm in supination. Care must be taken to identify and avoid damaging the posterior interosseous nerve, the superficial radial nerve, and the radial artery.

- The dorsal (Thompson) approach to the radius provides access to the extensor side of the bone where the placement of the plates should be if possible. The patient is again supine with the forearm either pronated on an arm board or supinated and placed across the chest. The critical aspect is protecting the posterior interosseous nerve.

Clinical Significance

The primary pathology involving the radius and ulna arises from fractures, which can be classified based on specific patterns and sites of involvement. Fractures usually occur in the middle third of the bones and can involve dislocation of the nearest joint due to the transmission of force via the interosseous membrane. Regardless of the site of the fracture, management should begin with a history and physical followed by plain films of the affected site, and if possible the joint above and below, orthogonal radiographic views of each site are mandatory to appropriately manage each fracture within the guidelines of the standard of care management. Common fractures include[30]:

- Dorsally displaced distal radius fractures (commonly referred to as "Colle fractures") – One of the most common forearm fractures. It involves a complete transverse fracture of the distal 2 cm of the radius. The distal fragment is displaced posteriorly resulting in the classic “dinner fork” deformity. The etiology is usually a fall on an outstretched hand with concomitant hyperextension. The fracture site can often be comminuted, and avulsion of the ulnar styloid process is also a feature.

- Reverse Colles fracture (Smith fracture) – A complete transverse fracture of the distal 2 cm of the radius with anterior displacement of the distal fragment. Usually secondary to a fall on a flexed hand.

- Monteggia fracture – A fracture within the proximal third of the ulna with concomitant dislocation of the radial head.[31]

- Galeazzi’s fracture – A fracture of the distal third of the radius with accompanying dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint.

- Barton’s fracture – An intraarticular fracture of the distal radius with concomitant dislocation of the radiocarpal joint.[32]

- Essex-Lopresti fracture-dislocation – Fracture of the radial head with dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint and rupture of the interosseous membrane.[33]

- Chauffeur fracture – An intraarticular fracture of the radial styloid process.[34]

- "Both Bone" forearm fractures - descriptive term to describe many different types of patterns involving fractures of the radius and ulnar shaft long bone

Incomplete fracture patterns of the forearm:

- Isolated ulnar shaft fracture -(greenstick fracture of the ulna)

- Isolated "buckle" or "torus" fracture pattern of the radius

- Seen in pediatric patients as a manifestation of a pathologic force compromising one cortex of the bone (resulting in compression on one side depending on the direction of the force)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Ulna, Radius, Articular capsule, Triceps, Flexor digitorum sublimis, Flexor, Flexor profundus digitorum, supinator, Abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, anconeus, aponeurosis, Extensor carpi ulnaris, Flexor carpi ulnaris, Flexor digitorum profundus, Extensor carpi radialis brevis, Extensor pollicis longus, Extensor carpi radialis longus,

Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates