Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Sternoclavicular Joint

- Article Author:

- Thomas Epperson

- Article Editor:

- Matthew Varacallo

- Updated:

- 8/15/2020 11:36:09 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Sternoclavicular Joint CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Sternoclavicular Joint

Introduction

The sternoclavicular (SC) joint is a saddle-shaped, synovial joint that serves as the primary skeletal connection between the axial skeleton and the upper limb.

Structure and Function

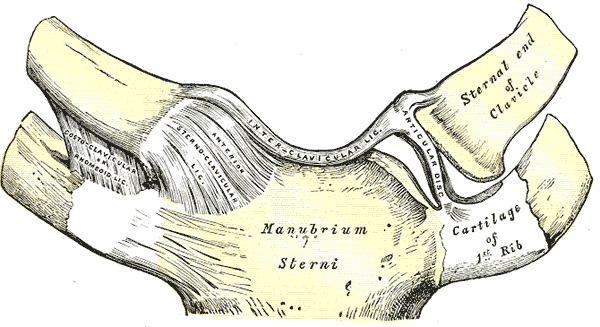

The SC joint articulates the clavicle with the manubrium of the sternum and the superior surface of the first costal cartilage. From an anteroposterior axis, the joint is convex. Vertically, the joint is concave. Structurally, the articulating surfaces of the SC joint are separated by a fibrocartilaginous articular disc which has functional mobility in the anteroposterior and vertical axis.[1]

The posterior sternoclavicular ligament provides the primary anteroposterior stabilization of the SC joint. It is a ligament that extends from the posterior aspect of the sternal end of the clavicle to the posterosuperior manubrium. The anterior sternoclavicular ligament also stabilizes the SC joint and prohibits excessive superior displacement. This ligament joins the medial end of the clavicle and the superior anterior edge of the manubrium. Other ligaments contributing to the stability of the SC joint are the interclavicular ligament which facilitates medial traction of both clavicles, and the costoclavicular ligament which mediates bilateral clavicle and anterior first rib stability. The costoclavicular ligament's orientation to the SC joint, anchoring the inferior surface of the sternal end of the clavicle to the first rib, serves as the primary restraint for the SC joint.

The subclavius muscle also functions to provide joint stability.

The SC joint is one of five articulations that permit fluid movement of the shoulder girdle. Functionally, it is a diarthrodial, multiaxial joint that provides 35 degrees range of motion for movement in the horizontal and coronal planes and 70 degrees range of motion anteroposteriorly. The joint is additionally capable of 45 degrees of rotation along its long axis. Mechanical input from the shoulder girdle influences the movements of the SC joint.

Important anatomical relationships concerning the SC joint are also worth noting. The brachiocephalic trunk, internal jugular vein, and common carotid artery lie posterior to the SC joint. Other mediastinal structures that lie posterior to the clavicle and SC joint are the vagus nerve, phrenic nerve, innominate artery and vein, trachea, and esophagus. The discussion of these structures and their implications in SC joint pathology will come later in this article.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Vascular supply of the SC joint derives from the internal thoracic artery and suprascapular artery. Both arteries are branches of the subclavian artery.

Nerves

The SC joint itself receives direct supply by the medial supraclavicular nerve (C3-C4) and the nerve to subclavius (C5-C6). It is also worth mentioning nerves involved in the various movements at the joint.

- Elevation: accomplished by the levator scapulae, upper trapezius, rhomboid major and minor muscles

- Innervation: dorsal scapular nerve, C5 ventral ramus, C3-C4 ventral rami

- Depression: pectoralis minor, lower trapezius, serratus anterior and inferior muscles

- innervation: medial pectoral nerve, spinal accessory nerve, long thoracic nerve

- Protraction: pectoralis minor, serratus anterior muscles

- Innervation: medial pectoral nerve, long thoracic nerve

- Retraction: middle trapezius, latissimus dorsi, rhomboid major and minor muscles

- innervation: spinal accessory nerve, thoracodorsal nerve, dorsal scapular nerve

- Rotation via elevation of the glenoid cavity: upper and lower trapezius, serratus anterior and inferior muscles

- Innervation: suprascapular nerve, axillary nerve, long thoracic nerve

- Rotation via depression of the glenoid cavity: levator scapulae, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis minor, rhomboid major and minor muscles

- Innervation: dorsal scapular nerve, thoracodorsal nerve, medial pectoral nerve, dorsal scapular nerve

Muscles

While no muscles immediately act on the SC joint, it is important to reinforce that the movement of the SC joint primarily depends on the motion of the scapula and the entire shoulder girdle, including the clavicle. Muscles inserting on the clavicle that influence movement of the SC joint are the deltoid, pectoralis major, trapezius, and sternocleidomastoid muscles. Other muscles influencing movement at the SC joint and their respective innervations are in the "muscles" section of this article.

Physiologic Variants

There are not many anatomical or physiological variations concerning the SC joint. However, some patients may have more prominent attachments of the ligaments supporting the SC joint than others, especially the costoclavicular ligament. This should not be viewed as pathological.

Clinical Significance

Trauma

Traumatic injury to the SC joint is rare, accounting for only 3%-5% of shoulder girdle injuries. [2] Given the strong stability and reinforcement of the joint, a significant force or a specific vector is often required to damage its structural and functional integrity, such as a motor vehicle collision or a direct blow from a contact sport or fall. Often, an indirect blow to the shoulder is the cause of a trauma that damages the SC joint. Direct blows to the medial clavicle are also frequent. Such blunt force trauma, if strong enough to disrupt the joint space, will lead to SC joint dislocation. Patients with direct trauma to the SC joint will often present with pain localizable to the joint itself. They may complain of shoulder pain or pain in the anterior chest. Often, the patient will have a prior history of trauma, but this is not always the case, as some SC joint injuries may be insidious in presentation. Physical exam may likely reveal swelling, bony prominence of the sternum or clavicle, pain and tenderness, ecchymosis, etc., in addition to severe pain and reduced range of motion of the shoulder joint.

- Dislocation: 1%-3% of all dislocations. Depending on the direction of the injuring force, SC joint dislocations can either be anterior or posterior in orientation.

- Anterior dislocations result from blows in an anterolateral direction. They are more common than posterior dislocations.

- Posterior dislocations are the result of blows in a posterolateral direction. Posterior SC joint dislocations put mediastinal structures at risk. The physician should note any sign of dysphagia, stridor, dyspnea, paresthesia, diminished extremity pulses or cyanosis. Potential complications of posterior SC joint dislocations include pneumothorax, brachial plexus injury and vascular injury, dysphagia, and hoarseness.[3][4][5][6]

- Sprain: no joint laxity or instability.

- Subluxation: tearing of sternoclavicular ligaments, but costoclavicular ligaments intact.

SC joint injuries are classified on the following basis depending on the extent of injury[2]

- Type 1: SC joint sprain without laxity or pain

- Type 2: SC joint ligaments rupture, costoclavicular ligaments intact. Subluxation.

- Type 3: SC joint ligaments and costoclavicular ligaments ruptured, dislocation of joint

Treatment of SC joint injuries is conservative if atraumatic. In anterior dislocations, conservative management is the recommendation. Acute posterior dislocations without evidence of mediastinal injury require management with closed reduction. However, if there are signs of mediastinal injury, emergent open reduction and internal fixation are warranted.

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis, a condition seen predominately in patients over 60 years of age, is relatively common in the SC joint, with one study showing a prevalence of 89% in patients above 50.[7] Pain associated with osteoarthritis is produced by forward flexion or abduction of the arm. Radiographically, osteoarthritis shows features such as subchondral cysts, joint space narrowing, osteophytes, and subchondral sclerosis.[8] Treatment is primarily conservative.

Infection

Infection of the SC joint is rare and presents insidiously with a low-grade fever, erythema, mild shoulder discomfort, and joint swelling. The primary organisms responsible for infection of the SC joint are Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Diagnosis involves arthrocentesis and MRI to assess joint integrity. Treatment is surgical debridement, en bloc resection, and antibiotic therapy.[9]

Gout

While uncommon, gout is known to affect the SC joint. Joint aspirate will reveal negatively birefringent crystals under polarized light.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, especially females, involvement of the SC joint is common.[10]

Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies

Conditions including psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and reactive arthritis, notably seen in patients who are HLA-B27 positive, are associated with involvement of the SC joint. SC joint involvement is much more common in psoriatic arthritis, with an incidence of 90% in severe cases. Treatment of these conditions revolves around non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and disease-modifying agents.[11]

Synovitis-Acne-Pustulosis-Hyperostosis-Osteitis (SAPHO) Syndrome

In patients with SAPHO syndrome, the SC joint is the most common location of skeletal involvement. Radiographic imaging of the SC joint in patients with SAPHO syndrome will show evidence of inflammatory hyperostosis on CT scan and a "bull's horn" appearance on a bone scan. Treatment of this condition is primarily using NSAIDs, steroids, bisphosphonates, and sulfasalazine.[12]

Condensing Osteitis

Condensing osteitis is a rare condition that presents with a painful and swollen SC joint. Abduction of the arm may exacerbate the pain. Radiographic evaluation reveals sclerosis of the inferomedial end of the clavicle without signs of bone damage. Histological examination of affected bone reveals reinforcement of cancellous bone and destruction of marrow spaces, and radionucleotide scanning will show increased uptake. NSAIDs are the mainstay of treatment.[13]

Friedrich's Disease

Friedrich's disease, the name given to the avascular necrosis of the medial clavicular end, can present similarly to condensing osteitis. A key differentiating factor between the two conditions is the duration of symptoms. Friedrich's disease presents typically with a shorter duration of clinical symptoms. Additionally, Friedrich's disease is predominantly seen in the adolescent and pediatric patient population. Histological examination of bone in a patient with this disease will reveal bone necrosis, marrow and Haversian canal fibrosis with empty lacunae. Like condensing osteitis, treatment is with NSAIDs.[13]

Other Issues

Imaging Considerations

The SC joint is best imaged utilizing computed tomography (CT) scanning for three-dimensional analysis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be used to analyze the articulating surfaces, fibrocartilaginous articulate disc, and supporting ligaments of the SC joint.