Genetics, DNA Packaging

- Article Author:

- Brittany Simpson

- Article Author:

- Hajira Basit

- Article Editor:

- Nora Al Aboud

- Updated:

- 6/11/2020 10:28:58 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Genetics, DNA Packaging CME

- PubMed Link:

- Genetics, DNA Packaging

Introduction

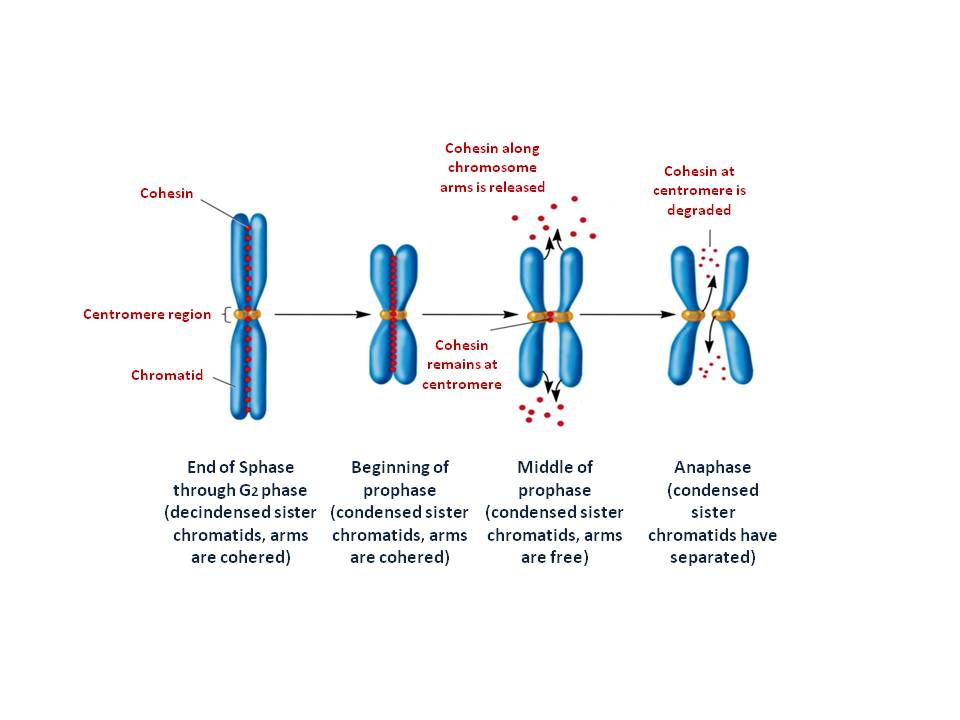

Eukaryotic nuclear DNA is a well-organized entity packaged into nucleosomes, the single unit for chromatin, condensed further into individual chromosomes. A chromosome is packaged efficiently for systematic DNA replication, ensuring DNA's intact propagation into the next generation of cells as well as organizing different genes and regions of the genome for specific cellular functions. Replication occurs at many origins of replication throughout the chromsome, approximately 100,000 base pairs apart in the DNA. Different signals along the DNA's packaging can alert differing cell machinery to either suppress or increase expression of certain sections of the DNA or specific genes. Under the microscope, metaphase chromosomes appear as "X's" with a constriction or centromere in the middle. This centromere functions as a place of attachment for machinery to help separate sister chromatids during cell division. This machinery for separation is called the kinetochore, a complex of proteins that aid in ensuring the 2 sister chromatids go to opposite poles during mitosis and meiosis. Eukaryotic chromosomes also have telomeric regions on the ends of the chromosomes which prevent shortening during DNA replication.[1][2]

Molecular

All DNA is wrapped around structures called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes are composed of double-stranded DNA wrapped around an octamer of 8 histone proteins including two of each of the following: H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Nucleosomes are the basic unit for chromatin.[3] An additional histone protein, H1, binds to the DNA just next to the nucleosome and functions in creation of further compaction and more complex chromatin structure, discussed below. Histone stabilization occurs via numerous protein-protein interactions, hydrogen bonding and electrostatic forces.[4][5][6][4]

Roger Kornberg, a prominent DNA and chromatin biologist, proposed the model of nucleosome structure in 1974. The model was based on his biochemical experiments, x-ray diffraction studies, and electron microscopy images. Markus Noll's experiment, however, gave a visually interpretable result to understand how DNA wraps around the nucleosomes. His experiment began with nuclei not extracted DNA, making the structure of natural DNA more readily apparent.[7] His experiment favored the theory that DNA was wound on the outside of the nucleosome unit, and each nucleosome consists of approximately 200 base pairs of DNA.

The DNA wraps around this ball of proteins about 2 times, followed by a short linker region of about 20-60 base pairs long before another histone octamer or nucleosome forms. Each nucleosome is 10 to 11 nanometers in diameter. Approximately 146 or 147 base pairs of DNA associate with each nucleosome. The linker region varys in length depending on species and cell type, and the region of the chromosome that is being either transcribed or not transcribed. The nucleosome followed by a spacer followed by a nucleosome and so forth give it the appearance of beads along a string. In order to control DNA expression and regulation of genes, there are N-terminal "tails" sticking out from the histone protein.[8] These proteins tails can be modified by acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, and these modifications will affect gene regulation. Methylation suppresses expression. Acetylation increases expression.[3]

Nucleosomes are further condensed into loops, which further condense into chromsomes only during times of cell division to ensure systematic and accurate DNA inheritance into the next generation of cell. This efficient packaging not only serves as a way to fit the 6 feet of DNA into each cell, but it also allows for particular portions of the DNA to interact with each other systematically.

Cell division through mitosis and meiosis is covered through a different StatPearls review.

Further DNA binding proteins, known as non-histone proteins, are a large group of heterogeneous proteins that play a role in organization and compaction of the chromosome into higher order structures. The H1 protein is essential in these higher order structures.[9][10] Secondary structures to chromatin are the Solenoid model and the ZigZag model. The Solenoid model consists of tightly wound nucleosomes in a regular, spiral configuration containing 6 nucleosomes per turn.[11] The Zigzag model is a bit looser form of chromatin with irregular configuration. In this model, nucleosomes have little face-to-face contact. In both the Solenoid and the ZigZag model, fibers are 30-nanometer in size.[12]

From the solenoid size, chromatin is further packaged and condensed into chromsomes. Chromosomes have different regions called heterochromatin regions and euchromatin regions. Heterochromatin regions are tightly compacted there at the telomeres and centromeres, these regions of the chromosome are always heterochromatin, and they are always tightly packaged where the DNA is very tightly coiled around proteins.[13] These regions can be visualized microscopically through various stains applied to metaphase chromosomes. Even though DNA appears to be unorganized intranuclearly during interphase, there is still significant structure and partitioning of different chromsomal material within the nucleus. The DNA from individual chromosomes is not intertwined with other chromosomes but remains in specific regions of the nucleus called chromosome territories. These territories can help bring different genes into spatial relation with one another, which is felt to be an important regulator of gene expression.

In addition to the need for systematic compaction of DNA for replication and cell division, it is important for the interphase cell to have its DNA organized within the nucleus. This organization helps to section the DNA into different areas of cell expression among other functions. The nucleus consists of a nuclear double layered membrane matrix compiled of different types of proteins that ensure nuclear stability and facilitate nuclear organization. This organization is by no means static and a plethora of complicated mechanisms will change DNA expression temporally and geographically within the body. The nuclear lamina is just under the inner membrane of the nucleus, where scaffolding proteins and matrix attachment proteins live. Eukaryotic DNA is organized into loops, which can be quite variable in length from 25 to 200 base pairs long. Within the actual genetic code of DNA, there are specific sequences that allow for attachment of these MARs and SARs along the nuclear lamina. These regions are called matrix attachment regions (MARs) or scaffold attachment regions (SARs) where the DNA is bound to the matrix or scaffold of the chromosome, and the MARs are attached to the nuclear matrix creating these radial loops.[14][15][14] These areas do not have a common sequence within the DNA. They are either constitutive or facultative in nature.[16][17]

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance for abherration in DNA organization is broad reaching and is highlighted by many disorders of histone methylation including alpha thalassemia X-linked Intellectual disability syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, Coffin-Lowry syndrome and Rett Syndrome.[18][19][20][21][22][23]