Anatomy, Head and Neck, Retropharyngeal Space

- Article Author:

- Ani Mnatsakanian

- Article Author:

- Katrina Minutello

- Article Editor:

- Bruno Bordoni

- Updated:

- 7/27/2020 9:19:17 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Head and Neck, Retropharyngeal Space CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Head and Neck, Retropharyngeal Space

Introduction

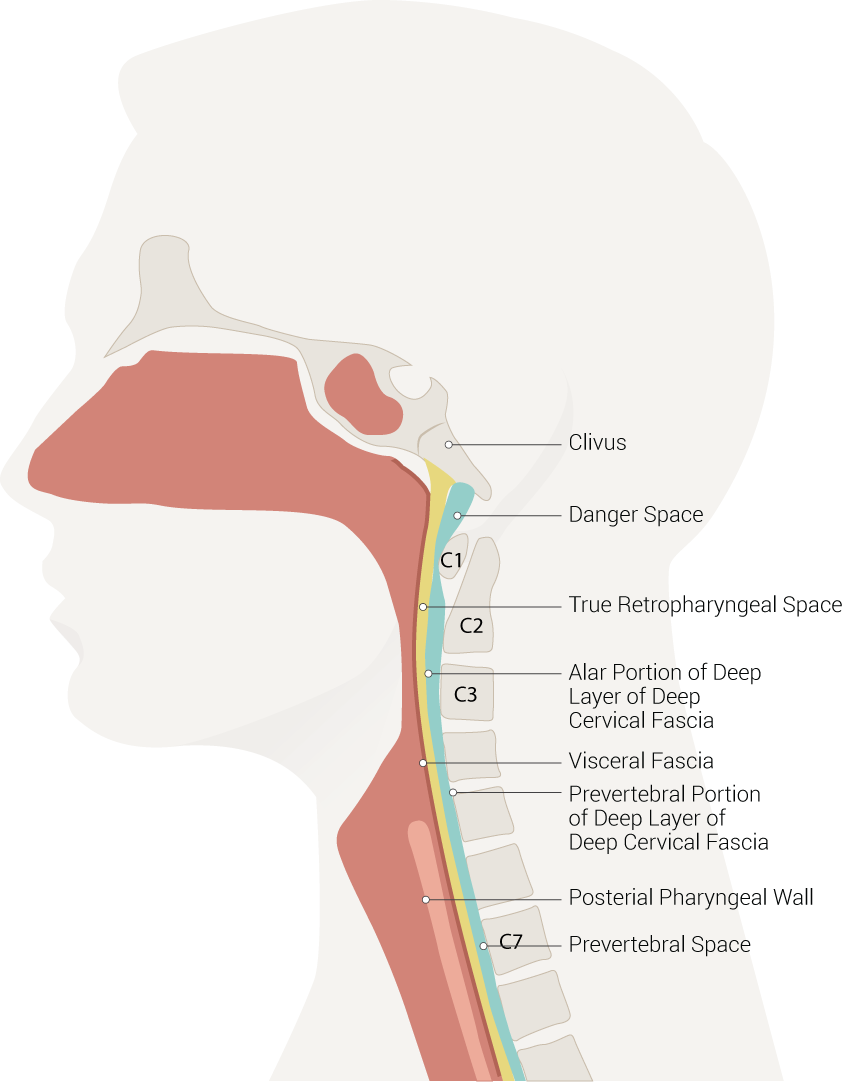

The retropharyngeal space (RPS) is an anatomical region that spans from the base of the skull to the mediastinum. Its location is anterior to the prevertebral muscles and posterior to the pharynx and esophagus. It's bounded anteriorly by the buccopharyngeal fascia, laterally by the carotid sheath, and posteriorly by the prevertebral fascia. The RPS is divided by the alar fascia into two components–the “true” retropharyngeal space and the “danger space.” The true RPS is located anterior to the danger space and extends from the base of the skull to between the T1-T6 vertebrae.

The termination of the true RPS along the upper thoracic spine (T1-T6) is variable based on where the alar fascia joins and fuses with the visceral fascia. The danger space courses more inferiorly than the true RPS, running into the posterior mediastinum until the level of the diaphragm. This anatomical connection between the pharynx and the mediastinum is where the danger space acquires its name as it serves as a potential channel for infection to spread between these two sites.[1][2]

Structure and Function

The retropharyngeal space functions as one of the deep compartments in the head and neck. It divides into suprahyoid and infrahyoid components. The suprahyoid RPS is composed of adipose tissue and lymph nodes. The infrahyoid RPS solely contains adipose tissue.[1]

Embryology

The structures of the head and neck, including the face, neck, and pharynx, derive from the branchial arches during weeks 4-7 of gestation. Six pairs of branchial arches form in cranio-caudal succession. The arches are composed of mesoderm and neural crest cells and give rise to cartilage, muscles, and nerves of the head and neck. They are surrounded externally by branchial clefts, which are ectodermal in origin, and lined internally by endodermal-derived branchial pouches. This branchial apparatus is responsible for the formation of all structures bordering the RPS. The branchial arches give rise to the fascial components lining the RPS, and the branchial pouches form the primitive pharynx.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Within the true RPS, lymph nodes and fatty tissue are the predominant tissues. The suprahyoid RPS houses the retropharyngeal lymph nodes, which are responsible for most of the lymphatic drainage of the pharynx. The retropharyngeal lymph nodes lie medial to the internal carotid artery and further divide into medial and lateral masses. The medial group atrophies throughout childhood, making children more likely to experience RPS infections than adults. The lateral group, named the nodes of Rouvière, persists throughout adulthood and can become a site of metastasis for head and neck cancers. The danger space is composed of solely adipose tissue and, therefore, can be affected by non-nodal diseases.[1][2]

The blood supply to the pharynx varies based on anatomic location. The superior pharynx receives its blood supply from the ascending pharyngeal artery and the lesser palatine arteries. The inferior pharynx’s blood supply comes from the superior thyroid artery and the inferior thyroid artery. Another significant relation to note is the proximity of the carotid sheath (internal carotid artery, common carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and vagus nerve) to the retropharyngeal space, composing the lateral border of the region.

Nerves

No nerves run within the retropharyngeal space, but it borders with many nerves. The pharyngeal nerve plexus and the pharyngeal venous plexus are on the buccopharyngeal fascia. This pharyngeal nerve plexus contains fibers of cranial nerves IX, X, and XI, and is considered the main sensory and motor nervous supply of the pharynx. The vagus nerve, running within the carotid sheath, gives off the recurrent laryngeal branch, which descends inferiorly alongside the pharynx. The recurrent laryngeal nerve innervates the intrinsic muscles of the larynx, apart from the cricothyroid muscle.

Muscles

The longus colli muscles serve as an important landmark for the RPS as they mark the location of the medial group of retropharyngeal lymph nodes from the lateral group of nodes. The medial lymph nodes are found anterior to the longus colli muscle, and the lateral lymph nodes are found ventral to the muscle. The prevertebral space is located directly posterior to the danger space and houses the levator scapulae, splenius capitis, scalenes, and splenius cervicis muscles. This anatomical relationship becomes important as a mass in the prevertebral space can be suggested by anterior displacement of the RPS.[1]

Physiologic Variants

In rare cases, the internal carotid artery can take an anomalous course through the retropharyngeal space; this may be congenital in nature, due to an improperly descended third aortic arch, and present throughout one’s life with symptoms such as dysphonia. It may be more evident in older individuals with a history of atherosclerosis and hypertension, both of which can exacerbate clinical signs and symptoms. This anomalous artery may increase a patient’s risk for vascular injury during surgery in the pharyngeal region and during intubation.[4]

Surgical Considerations

As described above, an anomalous internal carotid artery is an essential surgical consideration while operating in the pharyngeal area. There is a variety of disease pathologies that may occur in the RPS that could warrant surgery as one of the treatment options. These include:

- Retropharyngeal abscess: The two most common causes of RPS abscess are pyogenic lymphadenitis and peritonsillar abscesses. However, any cervical infection encompassing lymphatic drainage in the pharynx, prevertebral space, middle ear, or paranasal sinuses may lead to this pathology. Symptoms that can raise concern for a RPS abscess include fever, dysphagia, and a sore throat. These symptoms are non-specific and diagnostic imaging should be done to confirm a suspected abscess. A CT scan with contrast of the neck is the diagnostic imaging of choice and it will show a collection of fluid under tension in the RPS with rim enhancement. The retropharyngeal lymph nodes are also typically enlarged. An abscess in the danger space of the RPS can lead to spreading of the infection into the mediastinum. A RPS abscess requires surgical drainage as the first line of treatment.[1][2]

- Primary lesions of the RPS: lipoma, liposarcoma, synovial sarcoma.[1]

- Direct spread and metastasis: nasopharyngeal carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (pharyngeal, laryngeal, sinonasal, oral cavity), lymphoma, melanoma, esthesioneuroblastoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma, chordoma, primary spinal tumors, and thyroid goiters.[1]

- Fluid collection: There are a variety of disease pathologies that may cause a fluid collection in the RPS. These include foreign body ingestion, hematoma, angioedema, retropharyngeal lymphadenitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, Kawasaki disease, pyriform sinus, calcific tendinitis of the longus colli muscle, and cystic tumor caused by lymphatic malformation. The majority of these conditions will be referred to a surgical specialist for management.[2]

Clinical Significance

The retropharyngeal space is a significant region to consider when evaluating a patient with neck pain as a multitude of pathologies can manifest and affect this area. The connection of the danger space to the mediastinum allows for the spread of infections from the oral cavity to the thoracic cavity. Potential life-threatening complications related to infections in the RPS include mediastinitis and airway obstruction. These two conditions should certainly merit consideration when the RPS is involved in a disease process.

Other Issues

There is a smaller number of other etiologies that may present in the RPS which are often non-surgical in treatment. These include:

- Thoracic duct cysts: these are rare entities that may cause respiratory distress in the presenting patient, which most commonly link with trauma or a neoplasm. A potential treatment option for these individuals is sclerotherapy.[5]

- Retropharyngeal emphysema: the best definition of this condition is free air in the retropharyngeal space. The causes can include trauma, surgery, obstructive respiratory disease, substance abuse, bronchial asthma, and physical exertion, or spontaneous in nature. The clinical symptoms include dysphagia, neck pain, sore throat, and odynophagia. The recommended medical management includes an extensive history and physical, laryngoscopy for examination of the airway, barium swallow for monitoring of potential esophageal perforation, and imaging studies of the neck such as CT and plain radiographs. Most patients will resolve without intensive medical therapy as the condition is typically self-limiting and treatment is supportive.[6][7]

- Other lesions: foregut duplication cysts, leiomyoma, ectopic parathyroid adenoma, and disk bulge.[1]

(Click Image to Enlarge)