Zika Virus

- Article Author:

- Robert Wolford

- Article Editor:

- Timothy Schaefer

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 4:18:20 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Zika Virus CME

- PubMed Link:

- Zika Virus

Introduction

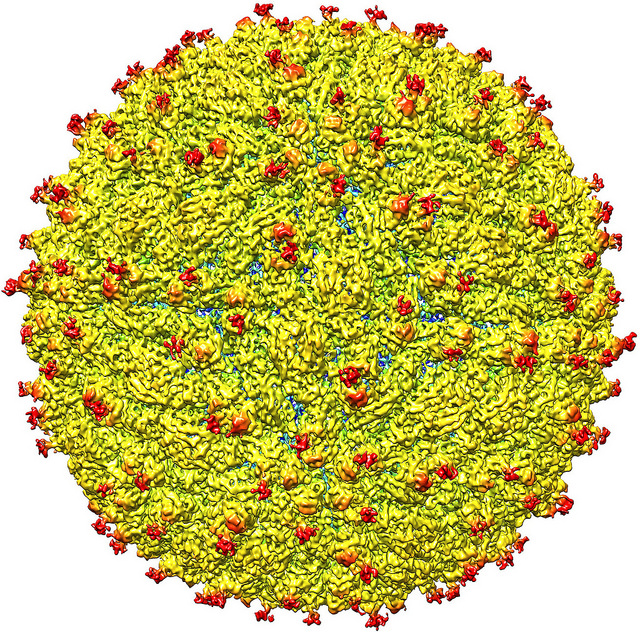

Zika virus is a single-stranded RNA virus of the family Flavivirus and the genus Flavivirus and belongs to two phylogenetic types: Asian and African. In the majority of people, infection by the Zika virus is mild and self-limiting.[1][2][3]

In most cases, Zika infection is a mild self-limited illness. Today, zika virus infection is a reportable illness.

Etiology

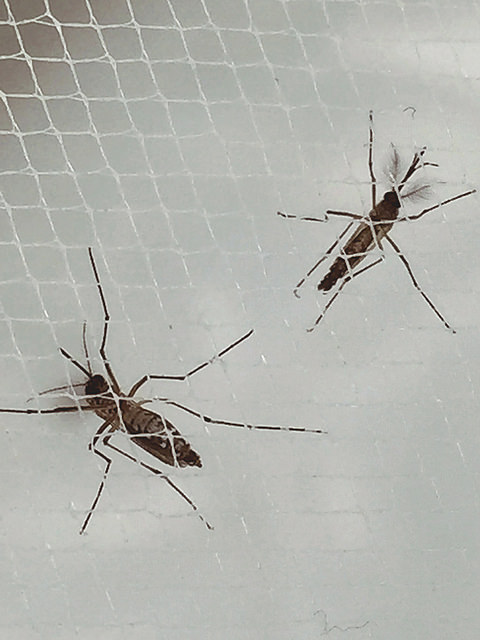

Diseases caused by Zika virus are predominately arboviral and transmitted by the bite of female Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Person-to-person contact (e.g., sexual contact), blood transfusion, organ transplantation, and perinatally (maternal-fetal vertical transmission) may also transmit infection. Zika virus is related to multiple other arboviral causes of human diseases, including Japanese encephalitis virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, West Nile virus, dengue virus, and the yellow fever virus.[4]

Epidemiology

Zika virus was first identified in Uganda in 1947 during a study of yellow fever virus. The first report of human infection was in 1954 in Nigeria. Subsequent studies suggested widespread distribution in Africa and Asia. Until 2014, there was no evidence of Zika virus in the Americas. Before 2007, there were no reports of large outbreaks of Zika infections. In 2007, an outbreak was identified on the coast of Central Africa, following suspected dengue and chikungunya epidemics. That same year, an outbreak was also identified in Micronesia (western Pacific Ocean). French Polynesia experienced outbreaks in 2013 and 2014 with subsequent outbreaks in 2015 to 2016, on other Pacific islands, including New Caledonia, Easter Island, Cook Islands, Samoa, and American Samoa. Cases of Zika infection were reported in Brazil in late 2014 and early 2015. It then rapidly spread through South and Central America. The first reported case of locally transmitted Zika in the continental United States was the week of July 24, 2016. As of April 19, 2017, 223 cases of Zika from presumed local, mosquito-borne transmission, have been identified (primarily in Florida) and 76 cases transmitted via other routes (46 sexual, 28 congenital, and two other) have been reported in the United States.[5][6][7]

Pathophysiology

The Zika virus is transmitted by the Aedes mosquito and several other Aedes species. Besides a mosquito bite, the virus can also be transmitted sexually.

History and Physical

Zika virus infection should be considered if the patient has a history of recent travel to an area with suspected Zika virus transmission or a sexual partner with recent travel to such an area. The duration of infectivity of bodily fluids following infection is unknown. However, Zika virus has been cultured from semen up to 90 days after symptom onset, and viral RNA has been detected in blood after 58 days and in semen up to 188 days.

Most patients with acute Zika virus infections are either asymptomatic (60% to 80%) or have only mild symptoms. For Zika disease due to a mosquito bite, the estimated incubation phase between bite and symptoms is two to 14 days. In symptomatic infections, the most common symptoms\signs include: rash (90% or more), conjunctivitis (55% to 82%), fever (65% to 80%), and headache (45% to 80%). The rash is typically maculopapular, and the fever is often low grade, and short-lived. Other common symptoms and signs include arthralgia (65% to 70%, myalgia (48% to 65%), and retro-orbital pain (39% to 48%). Less commonly seen are edema, vomiting, and abdominal pain. In areas with dengue fever and chikungunya, which have many symptoms and signs in common, it may be difficult to diagnose the etiology of the illness correctly. Conjunctivitis and rash more commonly are seen in Zika virus infections than dengue fever and chikungunya.

An increase in cases of the acute Guillain-Barre syndrome (a type of acute paralytic neuropathy) was observed during the French Polynesia outbreak. Although not proven to be the cause, it is suspected that Zika virus infection is likely a trigger of Guillain-Barre syndrome. Cases of acute myelitis and meningoencephalitis have also been reported following Zika virus infection. A complete neurologic examination is recommended when Zika virus is suspected.

Zika virus infection during pregnancy is the cause of a variety of congenital disabilities, including microcephaly and other brain abnormalities. For any women of reproductive age and areas conducive to possible Zika virus infection, the patient’s pregnancy status and short-term reproductive plans should be determined.

Evaluation

The testing for Zika virus infection is based on the risk of exposure, symptoms, and pregnancy status. Routine laboratory tests are frequently normal, although mild leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated hepatic transaminases may be seen.[8][9][10]

As of April 25, 2017, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) testing recommendations are:

- Test everyone with Zika exposure (living or traveling in areas with Zika or having sex with someone without a condom who has lived or traveled in a Zika area), and symptoms of Zika.

- Test pregnant women with Zika exposure.

- Test pregnant women with a fetus whose ultrasound demonstrates findings that might be associated with Zika infection.

- Zika testing should be part of the routine obstetrical testing at the first prenatal visit and during the second trimester for pregnant women with Zika exposure.

Test selection for detecting Zika virus infection is guided by the duration of symptoms (less than 14 days, more than 14 days) and pregnancy status.

The virus infection is detected with PCR and antibodies.

Treatment / Management

As noted, most cases of Zika virus disease is asymptomatic or mild. Treatment is supportive, encouraging rest, maintaining adequate hydration and the use of analgesics and antipyretics. If dengue fever is a possible etiology of the patient’s symptoms, aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided due to the hypothetical risk of hemorrhage and Reye syndrome. Individuals with Zika infection should be protected from mosquito exposure to reduce the risk of local transmission.[11][12][13]

Differential Diagnosis

- Dengue

- Chikungunya virus

- Malaria

- Yellow fever

Prognosis

Most cases of Zika virus infection are mild and resolve on their own. However, serious neurological disease has been reported including Guillain barre syndrome. In addition, there is great concern that the virus can induce congenital brain and eye malformations if acquired during pregnancy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention is the key intervention to avoid infection. This prevention includes using insect repellants, wearing appropriate clothing (long-sleeved shirts and pants), eliminating mosquito breeding sites (standing water in tires, birdbaths), and preventing entry of mosquitos into homes (screens). After traveling to a known Zika virus area, travelers should avoid mosquito bites for several weeks to prevent introduction locally.

Pearls and Other Issues

Pregnancy and Zika virus infection

During the current outbreak, the Brazilian Ministry of Health noted an unusual rise of newborns with microcephaly and other neurologic disorders and malformations. In the United States, fetuses and infants with congenital disabilities and confirmed Zika infections appear to be 30 times higher than baseline and infection during the first trimester had a higher proportion of deficits. Among completed pregnancies, laboratory evidence of Zika infection was associated with an incidence of birth defects of 5%. Congenital disabilities currently identified as associated with infection include:

- Microcephaly with partially collapsed skull

- Decreased brain tissue with brain damage

- Damage to the posterior eye

- Limited range of joint movement

- Increased muscle tone restricting body movement after birth

The complete spectrum of disorders associated with congenital Zika virus infection is not yet known.[14][15][12]

Currently, there is no treatment for Zika virus complicating pregnancy. Prevention is key. Pregnant women should avoid mosquito exposure, and avoid travel to known Zika virus areas, if possible. If unable to avoid exposure, testing, as described above, is recommended. If planning to become pregnant, the woman should avoid conception (abstinence or use of condoms) for at least 8 weeks after exposure or the start of symptoms. Men should avoid the risk of their partner conceiving (abstinence or use of condoms) for at least six months after exposure or initial symptoms.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The Zika virus has recently emerged as anew mosquito-borne viral infection. While in most people the virus causes a harmless infection, there are many reports indicating that the virus can cause both neurological and eye problems. In addition, Pregnant women are at very high risk for delivering an infant with microcephaly. The virus is also known to be transmitted sexually. There is no cure for the Zika virus, and thus prevention is the key. The nurse, primary care provider, and the pharmacist are key players in patient education. Pregnant patients should be educated about travel to the Zika endemic areas, most of which are in South and Central America. In addition, if they travel, prevention of mosquito bites is essential. Since the virus has located itself in many parts of the Southern USA, the public should be educated. The pharmacist should recommend appropriate garments, sleeping under a mosquito net and treating garments with permethrin. For travelers, the use of DEET is recommended. Because the virus is also transmitted sexually, the use of a condom is recommended during sexual activities. Anyone with a vision or neurological abnormalities should be immediately referred to the appropriate medical specialist. Finally, all pregnant women who have traveled to Zika endemic areas should be told to see an obstetrician. [16][17](Level V)

Outcomes

The majority of Zika virus infections are mild and self-limited. In fact, most are not even noticed by the patients.

However, in some patients, the virus may cause neurological symptoms like the Guillain Barre syndrome. In addition, there is great concern that the Zika virus can cause microcephaly and various ocular abnormalities.[18][19] (Level V)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)