Sural Nerve Graft

- Article Author:

- Ignacio Piedra Buena

- Article Editor:

- Matias Fichman

- Updated:

- 5/21/2020 8:08:20 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Sural Nerve Graft CME

- PubMed Link:

- Sural Nerve Graft

Introduction

Peripheral nerve injuries are a frequent condition commonly developed as a consequence of trauma. They may occur due to various mechanisms, including laceration, contusion, stretching, or nerve compression. Although not life-threatening, they can produce a considerable impact on the patient’s daily activities and overall quality of life. Restoration of the nerve continuity will aid in the recovery of its functions.

End-to-end neurorrhaphy is the preferred technique for transected peripheral nerve reconstruction. Despite this, it is not always feasible due to retraction of the nerve stumps, scarring, or nerve structure defect, which generates a gap. Consequently, making nerve coaptation either achievable with tension on the suture lines, which would have deleterious effects on the outcomes or be directly impossible.[1] In these situations, autologous nerve grafting plays a major role, with the sural nerve being the preferred donor site.[2]

Sural nerve harvesting was originally described as an open technique, but surgical technology improvements have led to the development of minimally invasive techniques that have expanded during the last decades.

The goal of peripheral nerve reconstruction with a nerve graft is to guide the regenerating axons towards the distal nerve stump allowing for end-organ reinnervation. The graft will serve as a scaffold that will guide the axon for regrowth towards the distal stump and finally into the end organ. It will also provide Schwan cells that will aid axon regeneration. Nerve coaptation should be done under magnification, localization of healthy proximal and distal stumps with a “bread-loafing” technique is mandatory before nerve graft interposition, a tension-free suture should be performed even under a full range of motion of the joint. Fascicle orientation and alignment is necessary in order to obtain the best results.[2] Under the optimal conditions, nerve regeneration will occur at a speed of 1 mm to 1.5 mm per day.[3]

Although surgical restoration of the nerve will improve the motor, sensory, and autonomic function of the end organ, reinnervation is not a synonym of complete functional recovery. Many factors, including the anatomic site of nerve disruption, the timing of reconstruction, the distance of nerve gap as well as patient characteristics like age and smoking status will have an impact on the final outcome.[4][5][6] It is the emerging understanding of these factors, that supports the idea that complete recovery is the exception to the rule.

Anatomy and Physiology

The sural nerve is a purely sensory nerve composed by roots L4-S1. Its origin is marked by the union of the lateral and medial sural cutaneous nerves, branches of the common peroneal, and posterior tibial nerves, respectively.[7]

The medial sural cutaneous nerve descends sub-facially between the heads of the gastrocnemius muscles along with the lesser saphenous vein. At the point of myotendinous union of the gastrocnemius heads, the nerve emerges subcutaneously through the deep fascia where it joins with the lateral sural cutaneous nerve forming the sural nerve. The nerve union usually occurs at the middle or distant third of the leg.

Sural nerve courses obliquely towards the posterior aspect of the lateral malleolus, where it curves anteriorly. During this final course, the nerve originates one collateral branch, usually 6 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus, the lateral calcaneus branch. Terminal branches are located 2 cm distal to the lateral malleolus, one branch turns to the lateral dorsum of the foot and anastomoses with the superficial peroneal nerve and the other branch reaches the lateral border of the foot.

The superficial sural artery and lesser saphenous vein accompany the nerve during its pathway, usually lying in a posterior position.

The previous description corresponds to the most common anatomical scenario the surgeon will encounter in around 74% to 84% of the patients, but some anatomic variations may be found. The anastomosis of the medial sural cutaneous nerve and the lateral sural cutaneous nerve may occur at a different height than the described. In 4% to 16% of the cases, there is no union of the lateral and medial sural cutaneous nerves. In 2.7% of the patients, the lateral sural cutaneous branch is absent.[7]

Indications

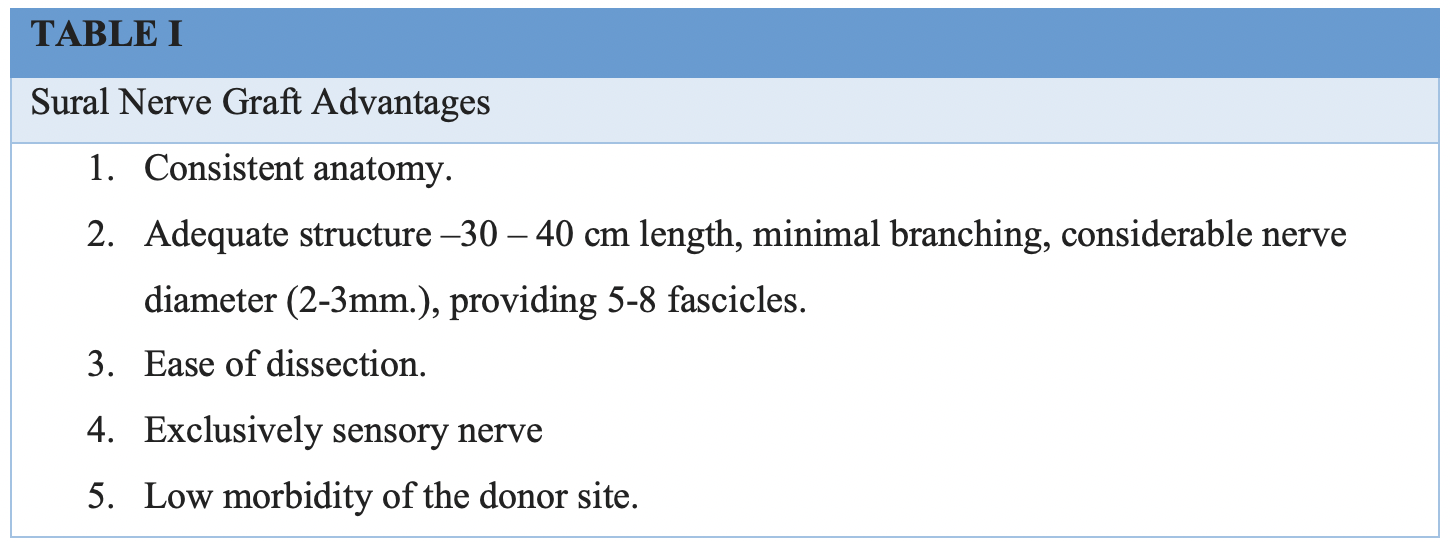

Indications for the use of sural nerve grafts are equal to the ones of other nervous grafts. Due to the advantages sural nerve graft offers compared to other autologous nerve graft options, it has turned into the gold standard donor site.[8] (Table I)

Nerve grafts are commonly employed when there is a segmental loss of a motor or sensory nerve of less than 6 cm. One requirement in order to achieve good results is the presence of viable proximal and distal nerve stumps. Facial reanimation with cross facial nerve grafting and posterior use of free functional muscle transfer corresponds to other common indications.[9] The use of nerve grafts has also been reported for nerve elongation in the context of brachial plexus injury.[10]

In recent years, nerve grafts have been used for corneal neurotization in patients suffering from neurotrophic keratitis. This condition is characterized by the presence of corneal anesthesia, which in turn produces the loss of the blink reflex and tear production. As a consequence, the cornea presents subsequent ulceration and scarring, which will finally result in opacification. In this context, sural nerve graft may be used to restore corneal sensation by anastomosing it to a functional sensitive nerve, usually the supratrochlear or supraorbital, redirecting its axons towards the affected cornea.[11]

Contraindications

Contraindications for the use of nerve grafts in a motor reinnervation procedure corresponds to the absence of functional motor units in the end organ. With time, the denervated muscle will atrophy and suffer fibrosis, losing its contraction capacity even if the nervous input is restored. This explains the importance of reconstructive timing. Another important consideration should be taken into account when the nerve defect is longer than 6 cm. In these circumstances, free vascularized nerve grafts are preferred over traditional nerve grafts.[12]

A free vascularized nerve graft may also be considered if the recipient site presents important scarring and is considered to have poor vascularization. Previous surgery or trauma involving the posterior aspect of the leg in the sural nerve course should discourage the procedure, and nerve indemnity should be investigated before proceeding.[13]

Another contraindication for the harvesting of a sural nerve graft is the presence of peripheral neuropathy that compromises the sensitivity of the lower extremity.

Equipment

A basic soft tissue surgical instrument tray is necessary for sural nerve graft harvesting. In order to perform the nerve anastomosis, 9-0 sutures are frequently employed in addition to microsurgical instruments that will aid in the performance of the neurorrhaphy on the recipient site. A surgical microscope is required for adequate magnification and visualization during this part of the procedure.

To perform minimally invasive sural nerve harvesting, endoscopic equipment is required.

Preparation

The procedure should be thoroughly explained to the patient and a family member. Understanding of the donor site morbidity consisting of anesthesia of the lateral calf and dorsum of the foot is of paramount importance. The presence of scars on the leg, mainly when performing the open harvesting technique, must be discussed ahead of the procedure.

Technique

The surgery is performed under general anesthesia. The patient is positioned in dorsal decubitus position. A two-team approach is possible in most of the cases. Nerve harvesting may be performed under tourniquet control to minimize bleeding during surgery, although this is not mandatory. Optical magnification with 2.5x loupes may be used during the procedure.

The standard preparation is performed with a 10% povidone-iodine solution circumferentially from the foot to the level of the knee in the selected donor leg. Drapes are positioned so that the lateral aspect of the leg is accessible, and the leg is mobile. The knee is usually flexed and a rolled surgical towel placed under the midfoot to maintain its position during the harvest.

A vertical zig-zag skin marking is performed at a point 1 to 2 cm posterior and 2 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus. An incision is made over the skin mark, dissection is performed reaching the subcutaneous fat. This step needs to be carefully performed with blunt scissors. Two structures will come into view; the lesser saphenous vein usually positioned lateral to the sural nerve. At this level, both of them are in a superficial position, visualization of the muscular fascia marks the endpoint of deep dissection required. It is important to identify and individualize these two structures before intensive manipulation of them is performed as this will collapse the vein lumen and make them difficult to differentiate. During initial dissection, the vein will have a blueish color, once recognized; usually, a blue silicone surgical loop is passed around it. Conversely, the nerve is identified and marked with a white surgical loop.

Proximal dissection of the nerve is conducted for as long as required. This can be done using a tendon or nerve stripper. However, blunt digital dissection is preferred to minimize the trauma generated to the nerve, which may finally compromise the surgical outcomes. Several horizontal incisions (two or three) are used on the leg as the nerve pathway is followed proximally in a "stair-step fashion," which will facilitate circumferential dissection from the surrounding soft tissue.

At the level of the union between the middle and upper third of the leg nerve deepening through the muscular fascia will be noted. Nerve dissection may proceed proximally until the needed length of nerve graft is achieved.

The nerve is perpendicularly cut proximally and distally with a new scalpel blade and extracted. The distal end of the nerve is marked with a surgical marker. This step is important as the nerve is reversed during inset.

Once correct hemostasis is achieved, leg incisions are closed in two planes with deep 4-0 vycril and 5-0 monocryl dermal sutures. Antibiotic ointment and gauze dressings are applied over the incision sites.

Variables to the open technique have been documented. The use of longitudinal or zig-zag incisions along the entire nerve course has been reported, although they worsen the aesthetic outcome without showing any real benefits in nerve harvesting or grafting results.[14]

During recent years, minimally invasive techniques with endoscopic assistance have been described for sural nerve harvesting. This approach decreases the number and length of incisions in the donor site showing a real benefit in the cosmetic result. Endoscopic visualization also offers a magnification of the image throughout throwout the procedure.

The procedure is executed in a similar manner, with circumferential preparation and draping of the leg from the foot to the knee level. An incision is performed at a point 1 cm to 2 cm posterior and 2 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus. In this case, the incision can be as small as 1 cm. Identification and marking of the lesser saphenous vein and the sural nerve is accomplished through careful dissection with blunt scissors in the subcutaneous plane and silicone loop placement.

Once identified, the nerve is dissected proximally on its superficial surface for a length of 1 cm or 2 cm. This will provide enough space for the placement of the endoscope. A rigid 5 mm endoscope is placed in the created space. Dissection will proceed proximally on the superficial side of the nerve for the required length and is assisted by the use of endoscopic instruments. Once the required nerve length is reached, the lateral and posterior nerve surfaces are released from the surrounding soft tissue in a distal to proximal manner. Encountered branches during the nerve course may be preserved or sacrificed according to the specific needs. Once completely freed, the distal and most proximal end of the nerve is cut, and the nerve can be extracted through the distal incision. Closure and dressing are performed in the same fashion as in the open approach.

A different option for fast 360-degree nerve detachment from the surrounding soft tissue is by the use of a nerve stripper, which will reduce surgical time.

Complications

Complications of sural nerve graft harvesting are common to any surgical procedure. Poor wound healing and hypertrophic scarring may be encountered and can generate concern in some patients. The development of a painful neuroma at the site of nerve proximal section is a rare complication after sural nerve harvesting.[15]

The presence of postoperative anesthesia of the dorsum and lateral aspect of the foot must not be considered as a complication but as a consequence of the sural nerve harvest.[16] This phenomenon will improve over a period of one or two years due to collateral sprouting of the adjacent sensory nerves.

Clinical Significance

The presence of nerve disruptions is a common clinical situation, usually resulting from trauma. In the presence of a nerve gap, the use of a sural nerve graft is an excellent resource to restore nerve continuity. The knowledge of the basic anatomy will allow the surgeon to harvest the nerve in a safe manner, minimizing the trauma generated to the graft itself that could diminish its functionality and hinder the outcome.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Postoperative care is an important aspect of nerve grafting. Hospital stay is brief, and patients can be discharged overnight. Pain killers are prescribed to manage any post-operative discomfort.

Immobilization by the use of splints is usually necessary for a period of 3 to 4 weeks to avoid any traction on the healing nerve ends where the neurorhaphy has been performed.

The patient needs to understand the goals of the surgery and the expected time of recovery. Care coordination must be assured between the surgeon and the physical therapist as rehabilitation is an essential component to achieve any results from the procedure. Patients commitment and compliance are imperative during the recovery process since it involves adhesion to a specific rehabilitation program with daily exercises and frequent office visits during a period of months. Improvements are slow, and the patient should not lose motivation.