Massive Transfusion

- Article Author:

- Lindsey Jennings

- Article Editor:

- Simon Watson

- Updated:

- 9/19/2020 9:08:07 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Massive Transfusion CME

- PubMed Link:

- Massive Transfusion

Introduction

Massive transfusion is traditionally defined as transfusion of 10 units of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) within a 24 hour period. The goal of massive transfusion is to limit complications and to limit critical hypoperfusion while surgical hemostasis can be achieved. This article reviews the current literature on massive transfusion protocols and explores the potential complications of this life-saving intervention.[1][2][3]

Patients potentially requiring massive transfusions can be seen across medicine from traumatic injuries, gastrointestinal bleeding, and obstetric catastrophes. While surgery is the most common use of major transfusion protocols (MTPs), trauma remains the best-studied category in massive transfusion. An estimated 3% to 5% of civilian trauma patients and 10% of military trauma patients will receive a massive transfusion. One study at a level 1 trauma center found that only 1.7% of all their patients underwent a massive transfusion, defined as 10 units within 24 hours. While the incidence of massive transfusion is relatively low, patients requiring massive transfusions have a high mortality.

Massive transfusion requires the consideration of multiple physiologic parameters such as volume status, tissue oxygenation, management of bleeding and coagulation abnormalities, and acid-base base balance.[4]

Volume Status and Tissue Oxygenation

The focus when a patient is in hypovolemic shock secondary to acute blood loss is to expand intravascular volume and maintain oxygen delivery to tissues. At baseline, oxygen is delivered to tissues at approximately four times the rate of oxygen tissue consumption. Therefore, volume expanders such as crystalloids may be employed during a massive transfusion to maintain blood pressure and tissue perfusion. However, if a patient is in severe shock, or if they continue bleeding, blood will eventually be required to maintain oxygen delivery at an appropriate rate.

Due to the surplus of oxygen delivery in a normal physiologic state, the body is able to maintain tissue oxygenation at below-normal hemoglobin levels. Ample evidence supports different hemoglobin “thresholds” at which a patient requires transfusion to maintain adequate oxygen delivery. However, it is important to remember that these transfusion guidelines are not helpful in the setting of acute blood loss. Hemoglobin is reported as a concentration. In acute blood loss, the hemoglobin concentration will remain the same. It is only after time and fluid shifts that the hemoglobin will lower. Therefore, hemoglobin “thresholds” cannot be used to manage transfusion in the setting of acute blood loss.

Acidosis

Patients requiring a massive transfusion are often acidotic even before transfusion begins. Prolonged states of hypoperfusion lead to acidosis. Once acidosis has set in, it further interferes with coagulation by reducing the assembly of coagulation factors. There is a direct relationship between decreasing pH (increasing acidosis) and reduction in the activity of coagulation cascade components. This results in delayed and thin fibrin clot formation, which is more quickly destroyed through fibrinolysis.[5]

Hypothermia

Many patients with acute, blood-loss anemia are also susceptible to hypothermia, which again can lead to coagulopathy. Lower ambient temperatures and decreased blood volume can predispose these patients to hypothermia. Hypothermia reduces the efficacy of both the coagulation cascade (by reducing the enzymatic activity of coagulation proteins) and platelet plug formation. At 34 C, effects on coagulation begin, and at 30 C, there is approximately a 50% reduction in platelet activation.

Coagulopathy and Dysfunctional Hemostasis

Due to massive bleeding, coagulation factors are often being consumed in patients who may require massive transfusion. Additionally, dilution of the remaining coagulation components due to volume expanders in addition to hypothermia and acidosis can lead to coagulopathy and altered hemostasis. The decreased ability to stop bleeding leads to further hypothermia and acidosis, creating a positive feedback loop that results in worsened patient outcomes.[6]

Indications

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications for massive transfusion.

Equipment

Gathering the proper equipment is an important part of massive transfusion. Access is necessary to deliver intravenous blood products adequately. Blood products can be delivered through peripheral intravenous (IV) catheters, central IV catheters, or through intraosseous (IO) catheters. With all of these catheters, the same principles of flow apply. The flow through a catheter described by the Hagen-Poiseuille equation. It is proportional to the change in pressure between points and the radius to the fourth power. It is inversely proportional to the length of the catheter and the viscosity. From this equation, we can conclude that the rate of flow is directly related to the radius of the catheter and inversely related to the length of the catheter. In most patients receiving a massive transfusion, we would like to give blood products quickly. Therefore, catheters larger in diameter and shorter in length will give us higher flow rates and are more desirable. Large-bore IV catheters (14 to 18 g), central IV catheters, and intraosseous catheters should be gathered and inserted into the patient as necessary keeping in mind that a few large-bore peripheral lines may have higher flow rates than some central catheters.

Other equipment such as high-speed transfusion devices and blood warming devices should also be collected. Materials to send frequent laboratory testing for hemoglobin levels, ABGs, coagulation, electrolyte, lactate, and thromboelastogram (TEGs), as well as point-of-care testing devices, should be collected, if available. There should also be monitors available for continuous reassessments of temperature, pulse oximetry, blood pressure, and heart rate.

Personnel

Massive transfusions require the coordination of physicians, nurses, laboratory testing, and the hospital’s blood bank. Many institutions have an alert system, similar to those used in the case of trauma, that informs the necessary personnel that a massive transfusion is likely to take place or is occurring.

Preparation

Healthcare professionals preparing for a massive transfusion should ensure that the patient is hooked to a monitor and there is adequate intravenous access to deliver the blood products when they become available. Notifying the blood bank will also help avoid delays in getting further deliveries of blood products if necessary.

Technique

Many institutions have created protocols for massive transfusion using knowledge from interprofessional teams. These institution-specific protocols facilitate ordering blood products and receiving them expeditiously from the blood bank. While these protocols vary between institutions, many massive transfusion protocols focus on delivering PRBCs in addition to platelets and fresh frozen plasma (FFP).[6][9][10]

While unfeasible for the general population, there is strong evidence from medical, military experience demonstrating positive outcomes when fresh whole blood is transfused to trauma patients. This has led to the concept of mimicking whole blood during massive transfusion by transfusing packed red blood cells (PRBCs), platelets, and fresh frozen plasma (FFP), with fresh frozen plasma supplying the coagulation factors. There is still controversy regarding the best ratio of these 3 components in the setting of massive transfusion. Many experts advocate for a 1:1:1 ratio of FFP, platelets, and PRBCs. Lower ratios of platelets and FFP have been used without evidence of inferiority, and the vast majority of massive transfusion protocols at trauma centers target lower ratios of plasma to PRBCs (80% trauma centers in a study of MTPs have greater than a 1:2 ratio of plasma to packed reds). The use of cryoprecipitate, fibrinogen concentrate, and recombinant factor VIIIa have been used with mixed results.

There is also strong evidence from the military that the use of tranexamic acid (TXA) can reduce coagulopathy and increase survival in patients with combat injuries, and further evidence that the addition of TXA in civilian bleeding trauma patients can reduce death. TXA works by inhibiting fibrinolysis or clot breakdown. Given its good safety profile and overwhelmingly positive results, it has been incorporated into many massive transfusion protocols.[11]

Targets of resuscitation in the setting of massive transfusion include:

- Mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 60 to 65 mm Hg

- Hemoglobin 7 to 9 g/dL

- INR less than 1.5

- Fibrinogen greater than 1.5 to 2 g/L

- Platelets greater than 50 times 10/L

- pH 7.35 to 7.45

- Core temperature greater than 35 C

Complications

Potential complications of massive transfusion include metabolic alkalosis, hypocalcemia, hypothermia, and hyperkalemia. Non-fatal complications have been seen in more than 50% of patients when more than 5 units of blood products are transfused.[12][13][14]

Metabolic alkalosis and hypocalcemia result from sodium citrate and citric acid that is added to blood products in storage to prevent coagulation. Each unit of blood can generate a total of 23 mEq of bicarbonate as citrate is metabolized. This can result in a metabolic alkalosis if the kidneys are unable to excrete the excess bicarbonate. Additionally, the alkalosis can result in hypokalemia as hydrogen ions move out of cells to compensate for the alkalosis through an H+/K+ transporter. Citrate also binds ionized calcium, which can lead to significant free hypocalcemia. It typically does not affect calcium bound to albumin. Severe hypocalcemia can result in paresthesias and cardiac dysrhythmias.

Hypothermia can also result from the infusion of blood products. Blood products are stored at 4 C. Rapid infusion of cold blood can lead to lower core body temperatures. Given that this population is already predisposed to hypothermia, which can further worsen coagulopathy, many rapid infusers also have warmers to reduce the risk of hypothermia during massive transfusion. Hyperkalemia is also a possible complication as potassium can increase in blood during long-term storage. It is typically only seen when blood products have been stored for long periods and are infused through central access at high speeds.[4]

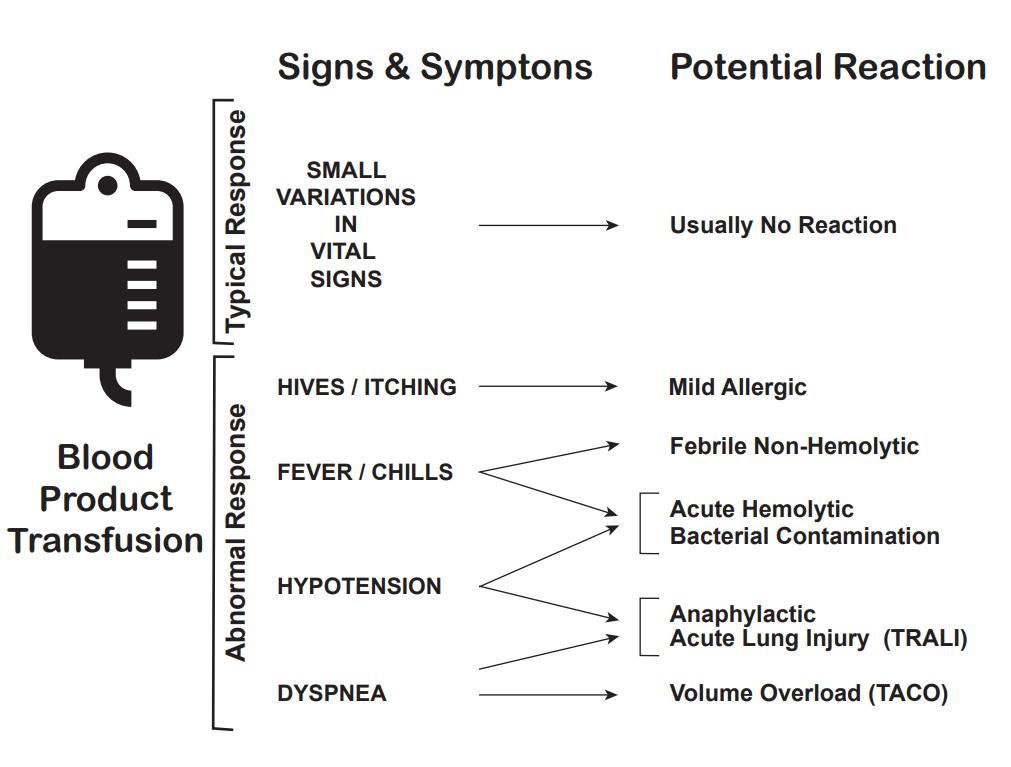

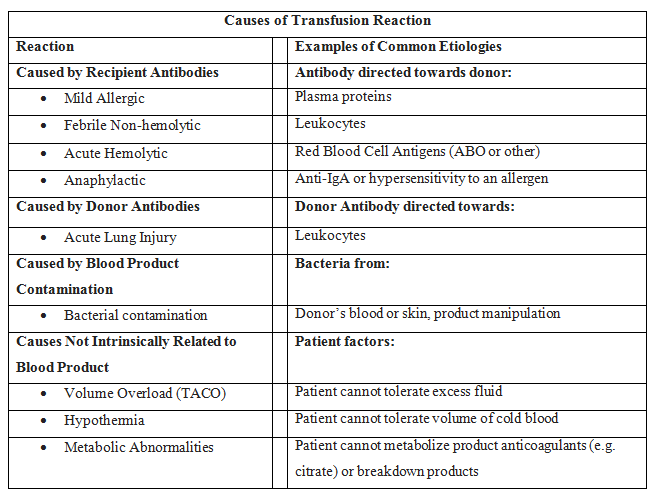

Additionally, the traditional complications of blood transfusion, specifically transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) can occur with massive transfusion. While the pathogenesis of TRALI is poorly understood, the incidence of TRALI increases as the number of blood products given increases. The rapid onset of hypoxemia indicates TRALI within 6 hours of a transfusion. Patients clinically will look very similar to those with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with a PaP2/FiO2 less than 300 mm Hg, bilateral infiltrates on chest x-ray, and no signs of systolic heart failure. TACO can also be seen with overzealous transfusion.[15]

Clinical Significance

Massive transfusion is an important life-saving intervention for patients with massive acute blood loss. Massive transfusion has been used in many clinical settings including obstetrics, gastroenterology, trauma, and the operating room. Although the etiology of bleeding is different in all of the cases, the same principles of massive transfusion apply. Massive transfusion can, however, have serious complications and should be reserved for patients with hemodynamic instability as a bridge to definitive therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Today, all healthcare workers should be very familiar with the healthcare institution's policy of performing checks and cross-checks before transfusing blood. This is mandatory and it applies to the laboratory technologist who prepares the blood, the nurse who receives the blood from the blood bank and the nurse who transfuses it; in short, all members of the interprofessional healthcare team. The aim is to prevent adverse reactions to blood. All patients must be educated about the potential for adverse reactions before administering the blood. Further, the nurse must tell the patient to inform her or him in cases they develop a fever, headache, rash or difficulty breathing. The nurse should also be aware that nonhemolytic febrile reactions do occur in 10-15% of patients who receive blood and hence good clinical judgment is required when to continue the transfusion and when to discontinue it. If an adverse reaction occurs, the nurse should immediately stop the transfusion, call the physician and send the blood back with all the tubing back to the laboratory. Caution should be exercised at every step because complications of blood transfusions do have the potential to kill a patient. [16][17] This is why the interprofessional approach is necessary, so that this strategy is only used when necessary, and optimally administered when in use. [Level 5]

Outcomes

In general, when massive blood transfusions are done especially in the setting of trauma, the potential for complications is high. Some studies indicate that no more than 20-30 units of blood should be given to avoid complications. Overall, most studies reveal that such transfusions do not lead to patient survival but in fact, are associated with many adverse events.[18][19] (Level V)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)