HIV-associated Lipodystrophy

- Article Author:

- Nilmarie Guzman

- Article Editor:

- Vini Vijayan

- Updated:

- 6/1/2020 4:13:25 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- HIV-associated Lipodystrophy CME

- PubMed Link:

- HIV-associated Lipodystrophy

Introduction

HIV-associated lipodystrophy is an undesirable effect of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) that occurs due to the redistribution of adipose tissue. The first reports of this condition were in 1997 among people taking ART. HIV-associated lipodystrophy includes both fat accumulation (lipohypertrophy) and fat loss (lipoatrophy) or both. Lipoatrophy occurs on the face, the buttocks, the arms, and the legs, whereas lipohypertrophy occurs in the truncal areas and manifests as abdominal obesity, mammary hypertrophy, accumulation of fat on the neck or lipomas. The body habitus, especially facial lipoatrophy, has links to depression, decreased self-esteem, sexual dysfunction, and social isolation and can affect the HIV-infected patient’s quality of life and adherence to ART.[1][2] Lipodystrophy also contributes to morbidity via the development of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and endothelial dysfunction, which can increase risk of cardiovascular disease and therefore identification and prompt management of HIV-associated lipodystrophy is of utmost importance.[3]

Etiology

The exact cause for lipodystrophy is unknown. However, the use of specific thymidine analog nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) such as zidovudine and stavudine are associated with the development of lipoatrophy. Switching to newer agents such as abacavir or tenofovir has been shown to prevent worsening. In contrast, although lipohypertrophy sometimes occurs with protease inhibitors (PI), switching or discontinuation of PI has not been shown to reverse fat accumulation.[4][5]

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of HIV-associated lipodystrophy has been challenging to establish due to differences in case definition, but estimates range from 10% to 80% among all people living with HIV worldwide.[6] The newer HIV medicines are thought to be less likely to cause lipodystrophy than the previously used agents.

Risk factors associated with lipoatrophy include exposure to NRTIs, mainly stavudine and zidovudine. The risk of development of HIV-associated lipoatrophy with other classes of antiretroviral therapy (ART), such as protease inhibitors or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) is unknown. Additional risk factors for lipoatrophy include HIV disease activity as measured by baseline CD4 cell count and viral load and host factors such as age and lower fat mass before initiation of ART.[6]

Risk factors for developing lipohypertrophy include increasing age, female sex, elevated baseline triglycerides, and higher body fat percentage. Although PI therapy was initially thought to cause lipohypertrophy, randomized controlled trials that substituted PI with alternative ART (e.g., non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs] or integrase inhibitors) in patients with lipodystrophy did not result in a decrease in visceral fat. Therefore, studies have not been able to definitively report an association between ART, especially PI and fat accumulation in HIV-infected individuals.[7]

Pathophysiology

The underlying mechanisms associated with HIV-associated lipodystrophy involve changes induced by HIV infection itself and metabolic changes triggered by certain classes of antiretroviral drugs.

HIV-1 virus infection per se results in a pro-inflammatory change in adipose tissue, which can contribute to lipodystrophy and the subsequent metabolic abnormalities. It stimulates expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alfa, IL-6, and IL-1beta) which induce a stress response in adipocytes leading to physical cell damage. TNF-alfa mediates insulin resistance by reducing insulin receptor kinase activity, which triggers apoptosis and lipolysis. It also downregulates the insulin receptor kinase substrate (IRS-10) and GLUT-4 transporter. Inflammation is thought to contribute to insulin resistance through impaired adipocyte metabolism and lipolysis.[8]

The mechanisms by which antiretroviral drugs play a role in the development of the lipodystrophy are incompletely understood. Protease inhibitors (PIs) and reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) have been shown to disrupt adipocyte function, lipid, and glucose metabolism. These drugs reduce adipocyte differentiation as well as expression, secretion, and release of adiponectin from adipose tissue. Adiponectin is a key player in glucose regulation and fatty acid oxidation. Antiretroviral drugs increase lipolysis and suppress lipogenesis, resulting in decreased free fatty acids (FFA) uptake by adipocytes and increase the release of stored triglycerides and glycerol in the bloodstream.[9] Mitochondrial toxicity induced by NRTI's also play a role in the development of the syndrome. This drug class is known to inhibit mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma; which stimulates catabolic activity by dysregulating production and synthesis of hormones and cytokines.

Mitochondrial toxicity, insulin resistance, genetics are also thought to be some of the additional pathophysiological mechanisms related to the development of HIV-associated lipodystrophy. Lipoatrophy correlates with severe mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation. Lipohypertrophy shares links to mild mitochondrial dysfunction and cortisol activation that are stimulated by inflammation. Further, both lipoatrophy in the lower part of the body and lipohypertrophy in the abdomen carry associations with metabolic changes that are similar to metabolic syndrome, especially dyslipidemia and insulin resistance.[8]

History and Physical

History

History must include detailed information describing patient and clinician-reported changes in physical appearance associated with the use of antiretroviral agents. Information about specific antiretroviral medications is a necessity as well as medicines used to treat comorbid conditions. The length of treatment with each ART, including PIs, NRTIs, NNRTI's, and/or integrase inhibitors is needed data. A personal and family history assessing for metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease should also is a requirement. A social history should include diet, exercise regimen, smoking, alcohol consumption, and illicit drug use. Patients may report sleep difficulties due to neck enlargement.

Patients should undergo evaluation for anxiety, depression, and a loss of self-esteem depression as well as compliance with ART. It is well known that lipodystrophy can cause patients to be non-compliant with ART.

Physical Exam

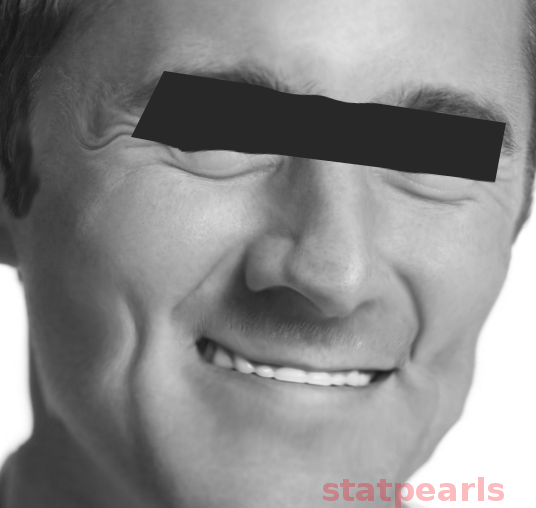

A physical exam should include body mass index, waist circumference, blood pressure, and clinical signs of lipodystrophy. The clinician should evaluate for features of lipoatrophy as manifested by loss of peripheral fat tissue noticed in the upper, lower extremities and buttocks as well as malar and temporal areas. Extremities appear thin with the prominence of superficial veins, and loss of facial fat causes sunken eyes and cachectic facial features.[1]

Patients with lipohypertrophy show accumulation of fat tissue in certain areas. For example, central lipohypertrophy characteristically present as intra-abdominal fat accumulation manifested by abdominal protuberance. Fat deposition can present in the dorsocervical area (buffalo hump), breast enlargement in both men and women, and the anterior neck and mandibular area. Lipomas can also be a feature.

Evaluation

All patients on ART should have monitoring for the development of lipodystrophy, which can be performed by measuring abdominal girth, hip, and mid-upper-arm circumferences. Monitoring of body weight and body mass index is of the utmost importance as identification, and early intervention is likely more effective than reversing fat accumulation.

Laboratory Data

The diagnosis of HIV-associated lipodystrophy is made based on the characteristic physical appearance of the patient. Due to the increased incidence of metabolic abnormalities in patients with HIV-associated lipodystrophy, lipid profile and glucose tolerance should be evaluated, ideally before the initiation of antiretroviral therapy and repeated every six months. Hemoglobin A1c may be useful; however, it may underestimate hyperglycemia due to increased red blood cell turnover in HIV infection. Liver and kidney function tests are necessary at regular intervals.

Treatment / Management

Treatment / Management

Treatment of HIV-associated lipodystrophy can improve the cosmetic appearance of the affected individual, improve their self-esteem, and compliance with ART. Treatment can also prevent dyslipidemia, abnormal glucose metabolism, atherosclerosis, and diabetes mellitus associated with HIV-associated lipodystrophy.

Recommendations are for multiple interventions in the management of HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome. These include modification of ART, use of thiazolidinediones, surgery, and lifestyle modifications. Management of HIV-associated lipohypertrohy includes diet and exercise, medical therapies with metformin, growth hormone releasing analogs, and surgical interventions.

Lifestyle Modifications

Counseling regarding the importance of smoking cessation, dietary modifications, and regular exercise is essential and is similar to that of healthy patients. Dietary counseling should focus on reducing the intake of saturated fats and cholesterol and increasing the consumption of vegetables, protein, and fiber-containing foods. A combination of cardiovascular and strength training can reduce visceral adiposity and improve muscle strength, lean body mass, and lipid levels.

Modification of Antiretroviral Therapy

Use of thymidine analogs, especially stavudine and zidovudine, is associated with HIV-associated lipodystrophy. Reversal of lipoatrophy is achievable by switching from stavudine or zidovudine to abacavir or tenofovir. Multiple trials have demonstrated improvement in the short term and slow improvement in lipodystrophy. Careful evaluation of the patient’s underlying co-morbidities such as hepatitis B and resistance profile should be taken into consideration when making a switch. Discontinuation or switching the protease inhibitor has not been shown to result in improvement of lipoatrophy.

Tesamorelin:

Tesamorelin is a growth hormone–releasing hormone analog, approved by the FDA for management of HIV-associated lipodystrophy. Administration of the drug is as a daily subcutaneous injection It has been shown to reduce visceral adipose tissue (VAT) approximately 15% in HIV patients after 6 months of therapy, but re-accumulation of fat can occur approximately 6 months after discontinuation of the drug. The most common adverse effects include fluid retention, arthralgia, myalgia, and decreased insulin sensitivity. Discontinue tesamorelin if significant increases in fasting glucose or HbA1C develop. Tesamorelin is contraindicated in patients with active malignancy, patients with a hypersensitivity to tesamorelin or mannitol, pregnancy, and in those who have a disrupted hypothalamic-pituitary axis.

Metformin:

Metformin is known to decrease body mass index (BMI) in patients with insulin resistance and can reduce VAT in some studies. [10] Metformin has shown to improve insulin resistance in HIV individuals as well as lipid and blood pressure benefits. There are reports in studies of improvement in endothelial functions and delayed progression of coronary calcium. Given its metabolic and cardiovascular benefits, it is commonly an option in HIV patients with lipodystrophy. For those patients on dolutegravir, it is crucial to keep in mind that it will increase metformin levels; therefore maximum recommended daily dose is 1000 mg.[10]

Surgery:

Plastic surgery can be a consideration for patients with severe lipoatrophy, which includes the use of temporary or permanent fillers. Temporary fillers currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for HIV-associated lipoatrophy include Poly-L-Lactic acid (PLLA) and calcium hydroxylapatite. Permanent fillers include agents such as purified silicone oil, polymethylmethacrylate, polyalkylimide, and polytetrafluoroethylene. These are not currently FDA approved. Permanent fillers are generally less desirable as lipoatrophy may worsen or improve with changes in ART resulting in unintended cosmetic effects.

Surgical management of lipohypertrophy includes liposuction and lipectomy. However, the duration of the effect is variable, and recurrence is common.[11][12][13]

Comorbidities

Dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and hypertension receive management according to guidelines used for the general population. When using pharmacologic interventions, providers should take care to avoid serious pharmacokinetic interactions, such as between statins and PIs. Also, efficacy impairment of antiretroviral therapy should be considered, including possible pharmacokinetic interactions and adherence.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for lipohypertrophy includes Cushing syndrome, glucocorticoid therapy, and obesity. Patients with obesity tend to have a large abdominal girth and pinchable subcutaneous truncal fat but those with HIV-associated lipohypertrophy have visceral, not subcutaneous fat deposition and hence this fat may not be pinchable. Fat accumulation in the posterior cervical region, otherwise known as a buffalo hump, may be due to Cushing syndrome and can be differentiated from HIV-associated lipohypertrophy by the presence of hypercortisolism.

The differential diagnosis for lipoatrophy includes malnutrition, hyperthyroidism, HIV wasting syndrome, anorexia nervosa, and cachexia secondary to cancer.

Prognosis

HIV-associated lipodystrophy progressively worsens when protease inhibitors and thymidine analog NRTIs therapy continues. The hypothesis is that with chronic HIV infection, the use of some antiretrovirals and lipodystrophy may accelerate the normal aging processes, leading to the early development of age-related comorbidities.

Complications

HIV-associated lipodystrophy is known to cause significant psychological distress and correlates with depression, decreased self-esteem, and social isolation. Patients may become non-compliant due to the fear of the development of lipodystrophy and concern that the presence of lipodystrophy may make the diagnosis of HIV obvious. Metabolic complications include hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia due to insulin resistance, which increases the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Neck enlargement can lead to neck pain and sleep apnea. Further, increased abdominal girth due to an increase in visceral fat accumulation can cause symptoms of abdominal distention and gastroesophageal reflux.

Consultations

- For patients who are candidates for tesamorelin therapy, endocrinology consult is a recommendation.

- A plastic surgery consultation is recommended for patients interested in fillers administration and/or removal of adipose tissue.

- A psychiatry or psychology consultation may be necessary for patients affected by undesired changes in body habitus.

- An infectious disease consult should take place when considering antiretroviral therapy switch.

Deterrence and Patient Education

When initiating patients on antiretroviral therapy, patient education is instrumental regarding potential adverse events and follow up process. Avoidance of anti-retroviral agents associated with lipodystrophy such as stavudine can prevent this disease. Currently, stavudine or zidovudine are no longer considered first-line regimens for treatment of HIV. Patients that are on these drugs should switch to other antiretroviral classes.

Pearls and Other Issues

- HIV-associated lipodystrophy characteristically presents as lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, or a combination of both in HIV-infected patients who are receiving antiretroviral therapy.

- The syndrome can have a significant impact on an individual's quality of life, both physically and psychologically.

- Treatment regimens containing thymidine analog nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) are most commonly associated with the syndrome and should not be the first-line treatment.

- HIV-associated lipodystrophy can be accompanied by hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia which contributed to morbidity.

- Management of lipodystrophy includes switching ART, lifestyle modifications, pharmacologic interventions, and surgical treatment.

- Because lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy are challenging to treat, prevention is the goal but avoiding agents that are associated with lipodystrophy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Recognizing and addressing HIV associated lipodystrophy represents a challenge given its multifactorial etiology and development over time. HIV infection and the use of specific antiretroviral agents are key factors in the development of the syndrome. Physicians taking care of HIV positive patients must closely follow glucose levels, lipid profile, and body habitus changes to detect metabolic changes secondary to antiretroviral drugs and make proper adjustments such as switching medications, adding hypoglycemic agents or lipid-lowering drugs.

A team approach is best for those patients with significant lipodystrophy, including a plastic surgeon, infectious disease specialist, nurse specialist, and endocrinologists; this can lead to the best potential patient outcomes.[10] [Level V] Consultation with psychiatry and/or mental health nurse is a recommendation for those patients being emotionally affected by body habitus changes.