Hemorrhoidectomy

- Article Author:

- Cosmina Cristea

- Article Editor:

- Catherine Lewis

- Updated:

- 7/10/2020 1:45:01 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Hemorrhoidectomy CME

- PubMed Link:

- Hemorrhoidectomy

Introduction

Hemorrhoidal disease is a common disorder requiring surgical intervention in approximately 10% of cases[1]. The overall prevalence is unknown because asymptomatic patients are less likely to seek medical help. Some sources estimate the incidence of symptomatic patients in the U.S is 4.4%, with patients between the ages of 45 to 65 years old being the most affected.[2][3][4]

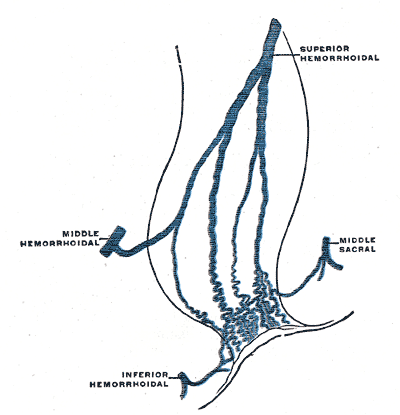

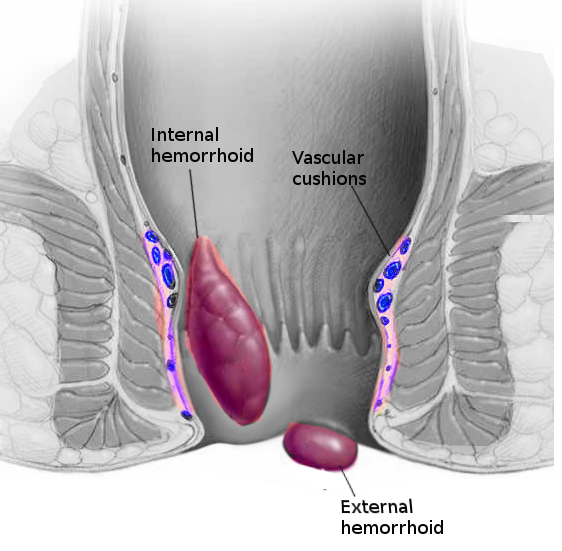

Hemorrhoids are columns of vascular connective tissue within the anal submucosa aiding in maintaining continence and bulk to the anal canal. The pathophysiology of hemorrhoids is mostly unknown, but one theory states that hemorrhoids develop due to varicose veins in the anal canal; however, most healthcare providers reject this idea. Instead, the current thought is that hemorrhoids develop due to decay or deterioration of the vascular cushions.[5] The three primary hemorrhoidal columns are in the left lateral, right anterolateral, and right posterolateral positions of the anal canal and can be either internal or external based on their location relative to the dentate line.[3] Internal hemorrhoids can be further divided on a scale from I to IV based on the degree of prolapse, which also helps guide the treatment options[2]. Patients presenting with symptomatic internal hemorrhoids complain of painless, bright red bleeding, described as streaks of blood in the stool, anal itching, pain, worrisome grape-like tissue prolapse, or a combination of these symptoms. External hemorrhoids are asymptomatic in most patients except for thrombosed external hemorrhoids, which cause significant pain due to their innervation by somatic nerves.[4][2]

Hemorrhoids can have treatment with both medical and surgical interventions depending on their degree of prolapse and whether they are internal or external. The most effective treatment for recurrent, symptomatic grade III, or IV hemorrhoids, is surgical excision. Surgical procedures primarily include closed, also called Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy, which is the most common technique in the United States, or the open, also called Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy, used in the United Kingdom and Europe.[4][2]

Anatomy and Physiology

Hemorrhoids are cushions of nonpathological vascular tissue in the anal canal. Microscopically, they have been described as sinusoids because they lack muscle, as do veins.[3] Several anatomic investigations have confirmed the existence of arteriovenous communications between vessels, which clarifies why hemorrhoidal bleeding is bright red and has the same pH as arterial blood.[6][5]

The anal canal is roughly 4 cm long in adults, with the dentate line marking its midpoint. Internal hemorrhoids develop above the dentate line and are painless due to their visceral innervation. They are covered by columnar epithelium and are classified based on the degree of prolapse. Prominent vessels and no prolapse characterize grade 1 hemorrhoids. Grade 2 hemorrhoids prolapse with Valsalva but spontaneously reduce. Grade 3 hemorrhoids also prolapse with Valsalva but need to be manually reduced. Grade 4 hemorrhoids are chronically prolapsed and cannot undergo manual reduction.[7] External hemorrhoids are covered in anoderm and are below the dentate line. They are sensitive to touch, stretch, and temperature due to somatic nerve innervation.[3]

Indications

Hemorrhoids can receive treatment with both medical and/or surgical interventions depending on their degree of prolapse and whether they are external or internal. One of the first and foremost conservative recommendations is a high-fiber diet. Garg recommends the addition of 4 to 5 teaspoonful of fiber that corresponds with the addition of 20 to 25 gm of supplemental fiber a day. For this method to be effective and not cause abdominal cramping, an adequate amount of water (500 ml) needs to be consumed at the same time with the fiber supplement for the water to be absorbed and result in soft stools. This intervention has proven to stop progression and help decrease the size of prolapse.[8]

Rubber band ligation and infrared coagulation are indicated for grade one and two hemorrhoids that fail medical management.[7] The reported number of rubber banding sessions is one, occasionally two, with a waiting period of four weeks between visits.[9] When comparing the two, long-term success favors rubber banding, whereas infrared coagulation is associated with less pain likely due to lack of mucopexy during the procedure. Overall, the failure rate of rubber band ligation is four times less than with infrared coagulation[2].

Operative hemorrhoidectomy is necessary for large third- and fourth-degree hemorrhoids in the following situations:

- Failed nonoperative management

- Advanced disease process unlikely to respond to conservative management

- Mixed hemorrhoids with a bulging external component

- Incarcerated internal hemorrhoids needing urgent intervention

- Coagulopathic patients requiring management of hemorrhoidal bleeding

Contraindications

Relative contraindications include the following:

- Patients unable to undergo general anesthesia due to medical comorbidities

- Baseline fecal incontinence

- Rectocele

- Presence of inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis

- Portal hypertension with rectal varices

- Uncontrolled bleeding disorder

Equipment

The classic instrument used for an excisional hemorrhoidectomy is the scalpel with or without the aid of scissors for dissection. This approach is highly effective and of low cost.

Ligasure and Harmonic scalpels are modern-day energy devices that have slowly come onto the medical scene. The added expense can negatively impact economic efficiency in the current reimbursement milieu. Ligasure is a bipolar cautery device used for both tissue division and coagulation of blood vessels. The Harmonic scalpel uses a reciprocating blade to generate heat for tissue division and coagulation. The proposed benefits of using energy devices relative to their cost have not demonstrated significant clinical advantages.[3]

Monopolar electrocautery is a device capable of superior hemostasis compared with a scalpel. It allows excision of the hemorrhoidal complex without suture ligation, but at the expense of injuring adjacent tissues due to lateral thermal spread.

A Hill Ferguson retractor is inserted into the anal canal to visualize the entire length of the hemorrhoidal complex. Other equipment that is needed may include:

- DeBakey forcepsMayo scissorsLarge Kelly clampAbsorbable sutures

Personnel

- Operating surgeon

- First Assistant

- Scrub Technician

- Anesthesia team

Preparation

Bowel preparation is not required; however, an enema may be necessary to clear the distal rectum of stool. No preoperative antibiotics are needed. Anesthetic selection should take place via a discussion between the anesthesiologist, the operating surgeon, and the patient. The patient should receive counsel that spinal anesthesia carries an increased risk of urinary retention. Prone jack-knife position with the buttocks taped apart is preferred by most American surgeons.[7] A lithotomy position is also an option.

Technique

Surgical excision occurs primarily through a closed hemorrhoidectomy (Ferguson technique), or open hemorrhoidectomy (Milligan-Morgan), which is more common in the United Kingdom and Europe. The Ferguson technique is the most common technique used in the United States, on which this article focuses.

The Hill Ferguson retractor is inserted in the anal canal to assess all three of the hemorrhoidal columns. The excision can be limited to only one column, but all three can be excised during the same operation if clinically indicated. The clinician should address the largest of the pathologic columns first.

The enlarged column should be compressed at the base with a DeBakey forceps to ensure the anoderm is tension free. A 10-scalpel blade is used to make an elliptical incision around the hemorrhoidal column. The pedicle is dissected off the surface of the internal anal sphincter using Mayo scissors up to the level of the pedicle. The pedicle is grasped with a large Kelly and is suture ligated with 3-0 Vicryl on a CT 2 needle. Deeper suture fixation of 3-0 Vicryl is used at the top of the anorectal ring to reduce the risk of recurrent prolapse. The suture is then used to close the rectal mucosa, anoderm, and perianal skin in a running fashion.

In addition to these conventional techniques, an additional surgical procedure is the stapled hemorrhoidopexy. During this procedure, the hemorrhoidal columns are not excised but are lifted above the anal verge and attached to each other. Studies show high rates of recurrence as well as microscopic incorporation of sphincter muscle in the resection specimens, which leads to transient flatus incontinence.[2][5][10]

Complications

The patient should anticipate pain and anal fullness within the first week following hemorrhoidectomy and hemorrhoidopexy. Adequate pain control, as well as the use of stool softeners, are a priority in the postoperative period.

Early complications include:

- Bleeding

- Urinary retention

- Thrombosed external hemorrhoids

Rare but life-threatening complications that must be recognized early include sepsis, abscess formation, massive bleeding, and peritonitis[2].

Late complications include:

- Anal stenosis

- Skin tags

- Recurrent hemorrhoids

- Delayed hemorrhage

- Fecal incontinence

Clinical Significance

Hemorrhoidal columns are a normal part of anorectal anatomy and require treatment when they become symptomatic. The first-line treatment includes conservative management, and the patient should receive education on fiber supplementation for adequate results.[3]

When medical management fails and the degree of prolapse advances, surgical excision is the preferred method of treatment. Success rates of removal are excellent, with low rates of recurrence. When comparing open and closed techniques, they both have similar rates of postoperative pain, need for analgesics, and complications.[7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hemorrhoids are widespread in society, and while easy to diagnose, the treatment is not always satisfactory. The disorder is best addressed by an interprofessional team dedicated to anorectal conditions.

All members of the healthcare team see patients with hemorrhoids in different settings, depending on the acuity and severity of the disease. Understanding the degree of prolapse of internal hemorrhoids helps the healthcare professional choose the adequate treatment and provide an appropriate education. Correct diagnosis of an acutely thrombosed external hemorrhoid leads to proper treatment promptly, which increases overall patient safety and satisfaction.

Several vital clinical recommendations are published for practice[2]:

- Increasing fiber intake is useful as a first-line medical treatment option.

- Grades 1 to 2 hemorrhoids can have successful treatment in an office setting with rubber band ligation.

- Excisional hemorrhoidectomy is only for grade 3 or 4, recurrent, or symptomatic hemorrhoidal disease.

Patient education is vital because hemorrhoids are preventable. The nurse, dietician, and pharmacist should encourage the patient to avoid constipation, drink ample water, be physically active, add fiber to the diet, and refrain from using too many pain medications (which cause constipation). The overall outcomes following surgery vary from good to poor. Residual pain and recurrence are not uncommon after almost every procedure. Interprofessional team management involving clinicians, nursing, and pharmacy can drive better patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

- Ensure the patient has given written consent

- Educate the patient about the treatment of hemorrhoids

- Help with patient positioning and prepping during surgery

- Assist the surgeon with the procedure

- Explain postoperative care

- Educate the patient on how to perform sitz baths

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

- Monitor the patient during surgery

- Monitor the patient in the post-operative period

- Check for bleeding after surgery

- Assess the level of pain after surgery