Cheiralgia Paresthetica

- Article Author:

- Jonathan Anthony

- Article Author:

- Andrew Hadeed

- Article Editor:

- Charles Hoffler

- Updated:

- 8/10/2020 4:21:08 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Cheiralgia Paresthetica CME

- PubMed Link:

- Cheiralgia Paresthetica

Introduction

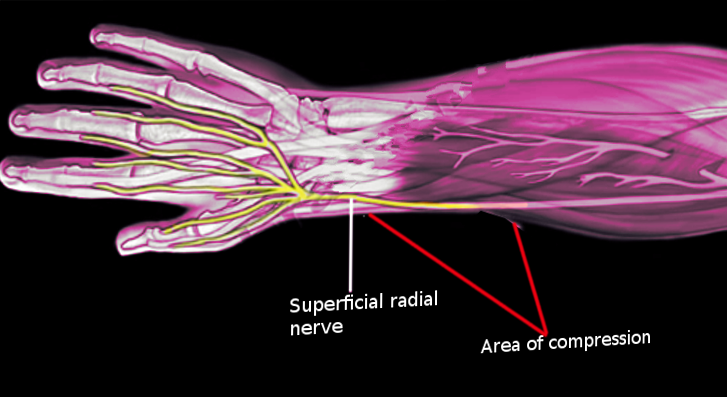

The radial nerve is susceptible to compression at many different locations throughout its course. Cheiralgia paresthetic is compression of the superficial branch of the radial nerve in the forearm. This condition was first described by Dr. Wartenberg in 1932 when he introduced the term cheiralgia paresthetica and reported five clinical cases.[1][2] It is also commonly known as Wartenburg syndrome and superficial radial nerve palsy. The superficial radial nerve is purely sensory and does not have any motor component. The condition presents with symptoms such as pain and burning located on the dorsal and radial side of the hand. Often it is aggravated by activities such as pronation, pinching, and gripping.

The radial nerve derives from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus and consists of fibers from the nerve roots at C5, C6, C7, C8, and sometimes T1. It descends between the long head of the triceps and axillary artery and enters the posterior compartment of the arm via the triangular interval. It continues to descend along the medial proximal upper arm between the long and medial head of the triceps until it reaches the spiral groove. The nerve passes distally and laterally around the posterior humerus, where it penetrates the lateral intermuscular septum and gains access to the anterior compartment of the brachium. The nerve enters the anterior compartment distal to the deltoid insertion at approximately 11 cm proximal to the elbow. It continues anteriorly to the lateral epicondyle between the brachialis and brachioradialis at the elbow to enter the forearm.

Roughly 3 to 5 cm proximal to the supinator, the radial nerve separates into the posterior interosseous nerve and the superficial branch of the radial nerve. The posterior interosseous nerve proceeds deep to the supinator. The superficial branch of the radial nerve continues superficially to the supinator and deep to the ulnar margin of the brachioradialis in the anterolateral aspect of the forearm to where it briefly runs alongside the radial artery. At roughly 9 cm proximal to the radial styloid process, it then pierces the deep fascia between the middle and distal third of the forearm, to emerge between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus to eventually become subcutaneous. The superficial branch of the radial nerve then ramifies again at approximately 4.9 cm proximal to the styloid process into dorsomedial and dorsolateral branches. These branches travel alongside the cephalic vein and proceed across the first dorsal compartment of the wrist and its tendons, the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis. The dorsolateral branch supplies the dorsolateral thumb proximal to the interphalangeal joint. The dorsomedial branch supplies the dorsomedial thumb proximal to the interphalangeal joint, dorsoradial half of the hand and dorsal aspect of the index, long, and radial half of ring fingers proximal to the distal interphalangeal joint.[3][4][5][6][7]

Etiology

The radial nerve can be compressed anywhere along its length. Due to the superficial location of the terminal branches, the nerve is at risk for local trauma.[8] Tight wristwatches and tight handcuff can compress the nerve over the lateral wrist.[3][4][9] Its superficial location predisposes it to injury from penetrating wounds.[6] It is also at risk for compression caused by distal radius fracture fragments of by soft tissue masses like lipomas or ganglion cysts.[1][9] The nerve is susceptible to iatrogenic injury during first dorsal compartment release, internal or percutaneous fixation of distal radius fractures, wrist arthroscopy, and external fixation placement. Seemingly innocuous procedures such as acupuncture, cephalic venipuncture, and cannulation, and radial arterial line removal complicated by thrombosis.[6][10] have been known to cause nerve palsies. Steroid injections into the adjacent tendon sheath for de Quervain's tenosynovitis can damage the nerve itself and can cause subdermal atrophy predisposing the nerve to injury.[6][8]

The nerve is more vulnerable where it passes from deep to superficial.[4] Compression may occur from fascial bands between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus and fascial rings of the dorsal brachioradialis. Repetitive supination and pronation and especially hyperpronation can trap the nerve between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus.[9] With forearm supination, these tendons are parallel to each other, and the nerve does not get compressed. When the arm moves into pronation, the extensor carpi radialis longus crosses beneath the brachioradialis and compresses the nerve.

Epidemiology

Cheiralgia paresthetica is a relatively rare condition when compared to other nerve compression syndromes. Carpal tunnel syndrome has an annual incidence rate between 0.1 and 0.35%; while, ulnar nerve compression syndromes have a rate of 0.02%. Radial nerve compression syndromes have a rate of 0.003%.[4] Cheiralgia paresthetic only makes up one subset of radial nerve compression syndromes. The annual incidence rate specific to cheiralgia paresthetica is unknown. It affects women more often than men at a ratio of 4 to 1. It is seen most commonly from ages 20 to 70.[11] It is not known to affect any specific ethnic group more than another.

Pathophysiology

This syndrome results from compression of the superficial branch of the radial nerve. The symptom and degree of injury are related to the amount of force on the nerve and the duration of compression of the nerve.[7] Compression can cause injury to the microvasculature of the nerve, the myelin sheath of the nerve, or the nerve itself. With mild compression, congestion and edema is the result of obstruction of venous flow, potentially leading to Schwann cell necrosis and demyelination from resultant ischemia. With severe compression, ischemia results from obstruction of arterial flow, which can lead to axonal injury and death from the resultant ischemia. The duration of compression also affects the nerve differently. Intermittent compression may lead to transient decreases in blood flow; while, chronic compression results in longstanding decreases in blood flow. These chronic changes can lead to demyelination, inflammation, scar formation, fibrosis, and eventual axonal degeneration.[3][6] It is crucial to remove the offending agent before severe nerve damage has occurred, for there is a better chance of recovery. Remyelination of the nerve itself may take a few weeks. However, axonal regrowth is very slow, only a rate of 1mm a day if at all possible.[3]

History and Physical

The patient presents with pain, tingling, paresthesias over the dorsolateral aspect of the hand, wrist, and fingers.[12][6] The symptoms may extend from the dorsal radial forearm into the thumb, index, and long fingers.[4] Much of the time, they are unable to localize the pain to a specific area. The patient often describes the pain as burning or shooting pain, as opposed to dull and achy pain. They may describe the sensation of numbness and tingling, although this is much rarer. The symptoms may be acute, intermittent, or chronic, which is related to the cause of irritation. Other symptoms can include tenderness, allodynia, dysesthesias, hypoesthesias. Specific motions, including flexion and ulnar deviation of the wrist, exacerbate the symptoms and can be magnified with pinching and gripping through this motion.

Visual

- Masses, scars, signs of external compression

- Skin changes

Sensation

- The first dorsal web space is specific to the superficial branch of the radial nerve

Light touch

- May be abnormal

- Up to 100% of patients

2-point discrimination

- May be abnormal

- 4 to 5 mm greater than the contralateral side or more than 15mm

- Up to 80% of patients

Vibration (256 Hz)

- May be abnormal

- Up to 100% of patients

Muscle strength

- No motor weakness or signs of atrophy

- May see a decrease in pinch and grip strength due to pain with these activities

- Up to 80% of patients

Tinel Test

- Most common finding

- Must test course of the superficial branch of the radial nerve and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve

- Identify the nerve segment with maximal Tinel response

Hoffman Test

- Evaluate for upper motor neuron pathology

Finkelstein Test

- May yield a false positive in up to 96% of patients

- Neuropathy may coexist with de Quervain tenosynovitis

Dellon Test

- Active, forceful hyperpronation of the forearm and ulnar deviation and flexion of the wrist with the elbow extended by the side

Wartenburg's Neuritis Compression Test

- Direct pressure at the insertion of the brachioradialis

Superficial Branch of the Radial Nerve Compression Test

- Direct pressure at junction of brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus causes symptoms

Optional Examination with Nerve Block:

Superficial branch of the radial nerve block with a local anesthetic

- Inject local anesthetic subcutaneously near the area of maximal Tinel Test

- Ultrasound guidance preferred to avoid nerve injury

- Finkelstein Test should become negative

- Measured pinch and grip strength should improve

Evaluation

Multiple diagnostic modalities can be used to evaluate for cheiralgia paresthetica. They include the following[14][6][14]:

Electromyography/Nerve Conduction Study

- Able to identify slowing nerve conduction velocities as compared to accepted normal values

- Commonly there is no slowing present

- Very helpful if present. May be able to identify the location and nature of nerve injury precisely

Ultrasound

- Can help distinguish between the different causes of wrist pain including cheiralgia paresthetica, de Quervain tenosynovitis, and thumb carpometacarpal joint arthritis

- Able to identify areas of nerve entrapment or compression

Plain Radiographs

- Able to identify any bony prominences or orthopedic hardware present

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- T1-weighted images can identify the nerve anatomy including any narrowing or enlargement that may be caused by its entrapment

- Water sensitive sequences including fat-suppressed T2-weighted, fat-suppressed proton density-weighted, and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) images can identify changes in the nerve itself including edema and enhancement

Treatment / Management

Management of cheiralgia paresthetica is mainly nonoperative therapy. Attention should first focus on removing sources of external compression that could be leading to the neuropathy. The patient should be encouraged to rest, avoid any provocative maneuvers, and alter any work activities that may exacerbate the symptoms. Also, NSAIDs and nerve medications can be used to augment therapy.[4] In refractory cases, temporary thumb spica splinting and ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injections are optional additions to the treatment regimen.[15] Underlying medical problems that may compound the symptoms require assessment and treatment. Reports are that up to 71% of patients treated nonoperatively have good to excellent outcomes.[4]

Surgery is only for failure of nonoperative treatment. Treatment should be attempted for 6 months before one proceeds with surgical intervention. Clinicians require caution when treating patients with painless paresthesias as surgical complications may create painful neurologic symptoms.[4] There are a number of surgical techniques described; many of these focus on the superficial branch of the radial nerve itself, including neurolysis, endoscopically assisted neurolysis,[16] neurolysis and nerve wrapping with material such as amniotic membranes and temporoparietal fascial flaps,[12] and microsurgical intraneural neurolysis. Other techniques focus on removing causes of compression including removal of lipomas, fascial bands, bony spikes, etc. and even longitudinal plication of the brachioradialis tendon.[13]

Surgical decompression: To approach the superficial branch of the radial nerve, palpate the radial styloid process and follow the border of the brachioradialis proximal 10 cm. Draw a line connecting the two. Identify the area with the most pronounced Tinel response, tenderness, and allodynia. Then center your incision over this. Carefully elevate skin flaps to identify the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus tendons. The superficial branch of the radial nerve generally appears between the two tendons with brachioradialis located above and extensor carpi radialis longus located below.[12] Carefully dissect out the nerve and free it from adhesions. Remove any masses, adhesions, or fascial bands that could be compressing the nerve. Once fully decompressed, one can choose to wrap the nerve in a number of different adhesive barriers, including but not limited to amniotic membranes or fascial flaps. The area of nerve compression is carefully measured, and the adhesion barrier is trimmed to match. It is then placed around the nerve and secured loosely in place with 8-0 nylon sutures if needed. Attention is necessary for circumferential coverage without strangulation of the nerve. Upon achieving vascularity is confirmed, and hemostasis, one can proceed with layered closure and application of a soft sterile dressing.[12]

Postoperative care should consist of early range of motion at directed by physical therapy with all restrictions lifted by 2 weeks after surgery. Occupational therapy should reinforce this early range of motion protocol and incorporate nerve gliding techniques to minimize adhesion formation, desensitization, and scar massage. Patients generally receive 4 to 6 weeks of therapy and achieve maximum medical improvement at 60 to 90 days after surgery.

Differential Diagnosis

de Quervain's tenosynovitis[14][4]:

- Stenosing tenosynovitis in the first dorsal extensor compartment

- Pain, tenderness, and swelling over the lateral wrist

- No sensory disturbance

- Cheiralgia paresthetica itself gives a false positive Finkelstein test. Although, it may be associated with de Quervain tenosynovitis. Up to 50% of patients with cheiralgia paresthetica also get a diagnosis of de Quervain tenosynovitis

Lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve neuritis:

- A lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve provides sensation to the lateral forearm

- Positive Tinel test over the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve may be mistaken for positive Tinel test over the superficial branch of the radial nerve

- The superficial branch of the radial nerve and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve neuritis may coexist

- The sensory overlap between the superficial branch of the radial nerve and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve in the dorsoradial hand occurs in 21% to 75% of patients. Cadaveric dissections demonstrated the connection comes from the lateral branch of the superficial branch of the radial nerve.

- Check Tinel's test just distal to antecubital fossa just medial to the brachioradialis where the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve exits deep fascia

- Tinel test may be positive in the course of the superficial branch of the radial nerve when there is a more proximal issue

- Must perform nerve block to lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve before the superficial branch of the radial nerve to rule out a false-positive superficial branch of the radial nerve block if overlap exists

Thumb carpometacarpal joint arthritis

- Pain at the in the radial aspect of the wrist

- Pain and weakness with motion, grip, and pinch

- Crepitus with motion

- Positive Grind Test: pain with a circular motion of thumb while applying axial compression

- Possible adduction deformity of the thumb carpometacarpal joint alone or in combination with a hyperextension deformity of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint (Z-type deformity)

- No sensory deficit

Proximal nerve lesion:

- Spinal cords lesions, nerve root compressions, brachial plexus injuries encompassing the posterior cords, radial nerve palsies, posterior interosseous nerve syndrome, and radial tunnel syndrome.

- Sensory disturbances will likely be associated with strength deficits.

Intersection Syndrome

- Pain in the dorsoradial aspect of the forearm

- Crepitus over the intersection of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis with extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor carpi radialis brevis

- No sensory deficit

Prognosis

The outcomes for treatment of cheiralgia paresthetica are promising. It is very common for patients to have spontaneous resolution of their symptoms. There are reports of up to 71% of patients treated nonoperatively have good to excellent outcomes.[4] After nonoperative treatment fails, there are reports of mixed results for surgical management. Lanzetta and Foucher reported a 74% success rate with surgical intervention; while Calfee et al. report only modest results with 55% of patients treated operatively continued to symptoms at follow-up of 3.5 years.[4] Gaspar et al. also state several patients treated with simple nerve decompression do not have reliable results. Neurolysis for entrapment of the superficial branch of the radial nerve has greater recurrence rates and worse outcomes when compared to other peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes.[12]

Complications

Complications include but are not limited to unsuccessful surgical decompression, persistent symptoms, worsening of symptoms, iatrogenic nerve injury or injury to surrounding structures, and wound problems.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Cheiralgia paresthetica can be treated well with straightforward nonoperative interventions. The key to treatment is an accurate diagnosis and identification of the cause of the compression. Once the cause is determined, patients should be educated on techniques to remove the compression and to avoid activities that will aggravate the symptoms. These conservative measures will lead to symptom resolution in the majority of patients.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cheiralgia paresthetica is a relatively common disorder that is underdiagnosed. The diagnosis is often confused with other wrist disorders. Successful management of cheiralgia paresthetica encompasses an interprofessional team approach. Clinicians, including the primary care provider and nurse practitioner who first see the patient, must be familiar with this disease and its presentation to diagnose it correctly. Having a high index of suspicion will lead to prompt diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Radiologists and neurologists can further verify the disease and identify the location of compression through imaging and electrodiagnostic tests.

Treatment initially consists of multifactoral conservative management with the removal of compression and avoidance of provocative activities. Brace therapy may be an initial approach with the input of orthotists. NSAIDs and other nerve medications may also be options; the pharmacist should verify appropriate agent selection, dosing, perform medication reconciliation, and counsel the patient regarding optimal NSAID use to avoid complications such as gastric upset, reporting any issues to the nurse or physician. If patients fail to improve with conservative management, a surgeon can remove anatomic nerve compression through a variety of techniques. Postoperatively, the patient will benefit from physical therapy and occupational therapy focusing on early range of motion, nerve gliding exercises, and avoiding activities that exacerbate the condition. Specialty-trained nurses can monitor progress and provide patient education at follow-up visits and also watch for adverse medication effects, and let the treating physician know if there are any concerns. Open discussion and communication with the patient and between all of the health care providers on the interprofessional healthcare team is key to the successful treatment of this disease. [Level V]