Hemorrhoid, Banding

- Article Author:

- David McKeown

- Article Editor:

- Scott Goldstein

- Updated:

- 7/31/2020 2:57:22 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Hemorrhoid, Banding CME

- PubMed Link:

- Hemorrhoid, Banding

Introduction

The popular technique of rubber band ligation for the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids was first described by Blaisdel,[1] but popularized by Barron in 1963.[2] The latter treated 143 patients in the office setting, where banding is typically performed, with excellent results. This relatively simple technique has been used to successfully treat grade 1 and 2 hemorrhoids. Some selective cases of grade 3 hemorrhoids can be treated with this technique as well. It is not necessary to have the patient take an enema prior to the procedure, and no sedation is required. The principle behind the procedure is that by causing ischemia to the hemorrhoidal tissue by placing a rubber band, the tissue will slough off in approximately one week leaving behind an ulcer, which allows it to heal and fix the tissue to the underlying muscle.

Anatomy and Physiology

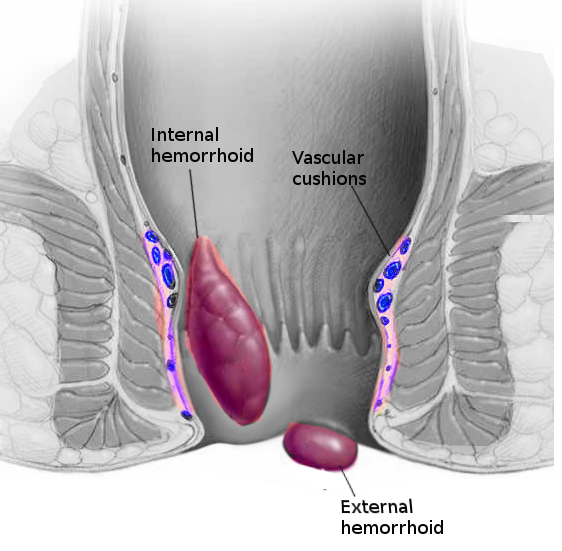

Hemorrhoids have been identified as cushions of vascular tissue located within the anal canal. Hemorrhoids themselves are normal but hemorrhoidal disease is not. Patients often have a poor understanding of anorectal complaints, and often referring providers have little training regarding hemorrhoidal disease. Internal hemorrhoids are vascular cushions that consist of elastic and connective tissue, and they are enveloped with Trietz suspensory ligament, which envelopes the entire corpus cavernous recti.[3] It is an extensive network of arteriovenous (AV) shunts and small vascular sinusoids which are arterial and have been proven so using blood gas studies. They are covered with columnar epithelium and do have innervation, which can cause discomfort. They contribute 15% to 20% of the resting anal pressure, and because of their arterial nature, when a patient performs Valsalva maneuvers, the sinusoids fill, and the resting anal pressure increases.

External hemorrhoids are distal to the dentate line, often confluent with the anal verge, enervated withs somatic sensory branches of the pudendal nerve. They contain the same sort of vascular sinusoids, but they are larger and predominantly venous. The slow flow through the external hemorrhoids leaves them prone to thrombosis. They are covered with squamous epithelium, the anoderm, and skin and are well innervated. They tend to appear in the classic anatomical spots of left lateral, right anterior, and right posterior, as described by Miles in 1919. Anywhere between 3-6 terminating branches of the hemorrhoidal arteries supply the area. This was demonstrated by Thomson in a cadaveric study in 1975.[4]

The pathophysiology of hemorrhoidal disease begins with a combination of straining, a poorly balanced diet, and poor bowel habits. This can lead to increased vascularity, inflammation, anal sphincter hypertonicity, and possible connective tissue enzymatic imbalance. This process leads to deterioration of Treitz muscle, which causes downward displacement of these cushions. The AV anastomosis distends and causes pooling in the veins and further worsens the deterioration in the muscle. The traditional concept of hemorrhoids being "varicose veins" is perpetuated in all medical dictionaries and most textbooks of medicine.

Indications

Rubber band ligation is indicated for grades 1, 2, and selected cases of grade 3 internal hemorrhoids.

Contraindications

Because of possible severe complications, rubber band ligation is contraindicated in patients with/on;

- Immunodeficiency

- Anticoagulation therapy

- Technical inability to pull sufficient tissue into the band ligator

- Anorectal Crohns disease

- Patients who are unlikely to follow up

- Concurrent anorectal infectious process

Equipment

There are several different rubber band ligation systems available. Some banders utilize a grasp, while others use suction to pull internal hemorrhoids into the banding instrument. With some devices, an atraumatic clamp is used to retract mucosa and redundant hemorrhoidal tissue at the apex of the bundle into the applicator, where a small rubber band is placed.

Personnel

An assistant, in addition to the primary proceduralist, is required for the procedure.

Preparation

Adequate lighting is essential for optimal visualization, as well. This results in a successful and precise procedure technique with little discomfort to the patient.

No specific patient preparation is required, although some surgeons may recommend an enema prior to the procedure. Most cases do not require any preoperative intravenous antibiotics.

The patient can be placed in the prone jackknife, lithotomy, or lateral decubitus position. This will be determined by surgeon preference, patient body habitus, and patient comorbidities. A morbidly obese patient may not tolerate the jackknife position and may require the lithotomy position.

Technique

Once the patient has been positioned adequately, and lighting has been optimized, a digital rectal examination is first performed. Four quadrant anoscopy is then performed, and the largest hemorrhoidal column is identified. It is important to delineate the dentate line as if a rubber band is placed too close to the dentate line; severe pain may occur as it has somatic innervation. The apex of the hemorrhoid is then grasped approximately 1 cm to 2 cm proximal to the dentate line. The forceps should be placed at the proximal point of the hemorrhoid, and the patient should be asked if they feel any pain or sensation of the grasper. This can be repeated to approach a more proximal portion of the hemorrhoid. The trigger is then pulled, and the elastic band is released. The grasper is removed and using the anoscope, the position of the rubber band is confirmed. This process can be repeated in other quadrants if desired.[5] It is important to note that if the patient complains of pain, the rubber band should be removed immediately.

Complications

Pelvic sepsis after rubber band ligation is rare. However, it is a potentially fatal complication.[6] It is vital that clinical suspicion remains high as early intervention is critical. Patients should be educated to seek medical attention if they have increasing pain, fever, or urinary retention, as this could be an early indicator of pelvic sepsis. The treatment for pelvic sepsis includes intravenous fluid resuscitation and antibiotics, as well as the removal of the rubber band and possible debridement of necrotic tissue in the operating room. It is imperative that the sepsis is treated early as the infection can develop into a necrotizing soft tissue infection or Fournier gangrene. Other complications include rectal bleeding, pain, acute external hemorrhoidal thrombosis, and possibly a vasovagal episode.[7] The bleeding typically presents between 3-8 days after banding as the tissue sloughs. This is usually self-limiting in nature.

Clinical Significance

Rubber band ligation has been studied in several large series, one study which looked at long-term outcomes of rubber band ligation included 805 patients who underwent 2114 ligations (median of two ligations in each patient).[8] There was a 71% success rate in this cohort. Success rates were similar for all degrees of hemorrhoids. When four or more bands were placed, the authors noted a higher failure rate.

A large meta-analysis of 12 trials, reported cessation of bleeding after rubber band ligation in up to 90 percent of patients; 84 percent of those with grade 3 hemorrhoids reported symptomatic improvement.[9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hemorrhoidal disease can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from other anorectal pathologies and, as such, may be treated incorrectly. The disorder is best addressed by an interprofessional team dedicated to anorectal conditions.

All members of the interprofessional team evaluate patients with hemorrhoids in different settings, such as the office, emergency department, or urgent care. An understanding of the degree of prolapse of internal hemorrhoids is essential and helps the healthcare professional choose the adequate treatment, the need for referral to a colorectal specialist, and provide an appropriate education. Correct diagnosis of an acutely prolapsed incarcerated internal hemorrhoid leads to proper treatment promptly, which increases overall patient safety and satisfaction.

Several vital clinical recommendations are published for practice:[10][9]

- Increasing fiber intake is useful as a first-line medical treatment option.

- Grades 1 to 3 hemorrhoids can have successful treatment in an office setting with rubber band ligation.

- Excisional hemorrhoidectomy should be reserved for grade 3 or 4, recurrent, or symptomatic hemorrhoidal disease.

The primary care physician, nurse, and pharmacist should encourage the patient to avoid constipation, drink ample water, be physically active, add fiber to their diet, and refrain from using narcotic pain medication. Interprofessional team management involving clinicians, nursing, and pharmacy can drive better patient outcomes. [Level 1]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Patients should maintain stool soft with hydration, fiber use, and stool softener.[11] Minor discomfort should be managed with acetaminophen. Office staff also help to ensure the patient has given written consent as well as educating the patient about the treatment of hemorrhoids. Nursing staff help position the patient and assist with the procedure.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Patients should be reevaluated and considered for a repeated banding attempt 6 weeks after the initial banding. Surgical excision can be considered for grade 3 hemorrhoids that persist despite banding. Medical assistants and nursing staff also help to monitor the patient during the procedure and follow up with the patient to check for bleeding and pain after the procedure.