Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Fascia

- Article Author:

- Leandra Jelinek

- Article Author:

- Stephanie Scharbach

- Article Author:

- Sarang Kashyap

- Article Editor:

- Troy Ferguson

- Updated:

- 10/30/2020 8:23:16 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Fascia CME

- PubMed Link:

- Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Fascia

Introduction

The anterolateral abdominal is the structure encasing the abdominal organs. It is the muscular layer of tissues that extends from the thoracic and lumbar spine to the anterior abdominal cavity. The boundary between the lateral and anterior wall is not defined, and therefore, the name anterolateral is used to describe the wall as it wraps from posterior to anterior. It serves to protect the internal organs of the digestive system as well as the alimentary tract. Multiple layers of fascia, muscle, nerves, and vasculature make up the anterolateral wall. The anterolateral wall demonstrates a vast degree of function as well as compliance for what the gastrointestinal tract needs. Throughout this article, we will explore the anatomy of the anterolateral abdominal wall, its function, and its embryologic origins.[1]

Structure and Function

The abdomen extends from the rib cage superiorly to the pelvis inferiorly. It contains the foregut, midgut, hindgut, and the alimentary tract needed for digestion and excretion. Multiple large blood vessels run through the posterior abdomen as well as multiple lymphatic pathways. This dynamic tract is in constant motion with continuously changing functions at any point in time. The abdominal wall is a structure that encases and protects all organs and vessels within the abdominal cavity. The multilayer abdominal wall expands and contracts with the alternating pressures of the abdominal cavity. It can contract when intra-abdominal pressures are needed to increase, for example, during defecation, exhalation, childbirth, coughing, vomiting, or just during the positional changes required during daily life. It also can expand with physiologic needs. The abdominal wall can accommodate increased abdominal girth, for example, obesity, childbirth, or postprandial state to accommodate the increased amount of food within the gastrointestinal tract. [2][3]

The multiple layers of muscles allow for a person to change position. The torso of the human body needs to be in constant motion, whether it be for walking, standing up, sitting down, or twisting from side to side. The multiple muscles have various orientations, insertions, and attachments to accommodate all directions of motion. Tasks accomplished through motion rely upon a constant dynamic of relaxation and contraction of the muscles and their effects on the surrounding bony structures to facilitate movement. There are many functions of the anterolateral wall; however, these would not be possible without the components that make up the wall.

Embryology

During the third and fourth weeks, the ventral side of the embryonic plate begins to fold, creating the anterolateral and anterior abdominal wall. The embryonic plate undergoes four folds: the cephalad, caudad, and two lateral folds. The lateral folds are responsible for the anterior abdominal wall, ultimately joining at the ventral ring by the end of the fourth week. The muscles arise from the mesodermal layer. The nerves extend from the origins of the spinal cord, creating dermatomes along the track through which it travels. These dermatomes will change shape and distribution as the fetus elongates after the initial embryonic plate folding.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

There are multiple large venous drainage systems as well as arterial systems supplying the anterolateral abdominal wall. The major arteries of the anterolateral abdominal wall are the superior epigastric, inferior epigastric, musculophrenic, subcostal, and posterior intercostal arteries, deep circumflex iliac artery, superficial circumflex iliac artery, and superficial epigastric artery. The four origins of the arterial supply of the wall are the internal thoracic artery, aorta, external iliac, and femoral artery—the internal thoracic artery branches to the musculophrenic and superior epigastric arteries. The musculophrenic descends along the costal margin and supplies superficial and deep layers of the abdominal wall in the hypochondriac region as well as the anterolateral diaphragm. The superior epigastric artery travels inferiorly through the rectus sheath into the deep rectus abdominis. The aorta is the origin of the tenth and eleventh posterior intercostal arteries and the subcostal artery.

The 10th and 11th posterior intercostal arteries travel past the ribs to descend into the abdominal wall between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles to supply the lateral superficial and deep lumbar/flank region. The subcostal artery travels the same course as the tenth and eleventh arteries and supplies the same regions. The external iliac artery supplies the inferior epigastric and the deep circumflex arteries. The inferior epigastric arteries travel superiorly and enter the rectus sheath, then travel through the deep rectus abdominis to supply the rectus abdominis muscle, deep abdominal wall of the pubic, and the inferior umbilical regions. The deep circumflex arteries travel through the deep abdominal wall, parallel to the inguinal ligament, then supply the iliacus, the deep inguinal region along the abdominal wall, and the iliac fossa—the femoral artery branches to the superficial circumflex artery as well as the superficial epigastric artery. The superficial circumflex artery travels subcutaneously along the inguinal ligament to supply the superficial abdominal wall of inguinal and anterior thigh regions. The superficial epigastric artery travels subcutaneously towards the umbilicus to supply the superficial abdominal wall of the pubic and inferior umbilical regions.[2][4]

The venous system consists of a large venous plexus throughout the abdominal wall. The plexus drains superiorly to the internal thoracic vein and lateral thoracic vein. Inferiorly it drains to the superficial and inferior epigastric veins.

Nerves

The neurovascular mapping of the anterolateral wall is an intricate network of blood supply and nerves. The dermatomes of the anterolateral wall are a clear representation of the peripheral nerve distribution. The dermatomes begin posteriorly and travel anteriorly, wrapping around the sides of the abdomen and meeting in the midline along the linea alba. Each dermatome has a slightly inferior slope, almost following the slant of the rib cage. Important dermatomes to remember are the T10 and L1 dermatomes, including the umbilicus and the inguinal fold. These are important to remember if a nerve block is needed for an umbilical or an inguinal hernia before an operation to decrease the postoperative pain the patient may experience.[5]

Major nerves to the anterolateral abdominal wall include the thoracoabdominal, lateral cutaneous, subcostal, iliohypogastric, and ilioinguinal nerves. The thoracoabdominal nerves are derived from T7-T11 and form the inferior intercostal nerves. These nerves run along the internal obliques and the transversalis muscles. They then enter subcutaneous tissue to become the anterior cutaneous branches of the skin in the anterior abdominal wall. The majority of these nerves innervate the muscles of the anterolateral wall, as well as the skin overlaying. The lateral cutaneous nerves innervate the skin overlying the hypogastric regions bilaterally. The subcostal nerve runs along the border of the 12th rib until it passes into the abdominal wall and runs through the second and third muscular layers. The subcostal nerve innervates the inferior portion of the external oblique, skin, superior region to the inguinal crest, and inferior to the umbilicus. The iliohypogastric nerve is the continuation of the superior branch of the anterior ramus of L1. It emerges through the transversalis muscle and runs along the second and third muscular layers of the abdominal wall, then emerges once again through the external oblique aponeurosis. The iliohypogastric innervates the transversus abdominis, and internal oblique muscles then become responsible for the sensation of the skin overlying the iliac crest, superior inguinal canal, and hypogastric regions. The ilioinguinal nerve extends from the inferior branch of the anterior ramus of L1. This nerve courses through the second and third layers of the abdominal wall until it transverses through the inguinal canal. This nerve is commonly encountered during open inguinal hernia repairs as it overlays the inguinal canal and, if severed, could cause loss of sensation in the inguinal region, mons pubis, medial thigh, and the anterior scrotum or labium majora.

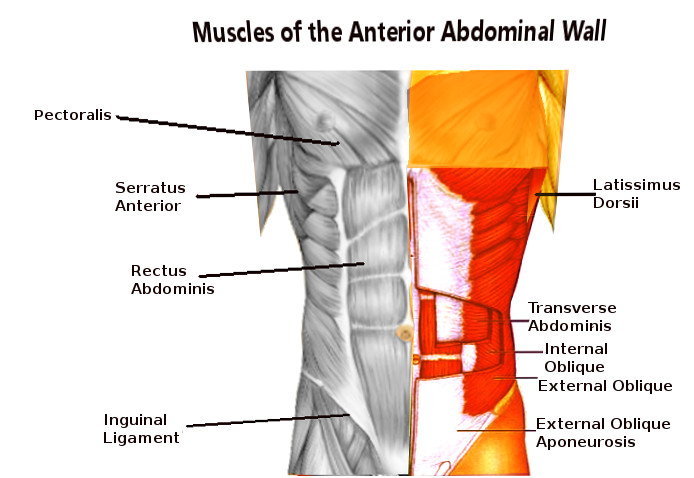

Muscles

The muscles of the anterolateral wall consist of five large, paired muscles. Beginning laterally and most superficially, the external oblique muscles are the first muscular layer originating from the fifth to twelfth ribs and inserting at the linea alba, pubic tubercle, and anterior half of iliac crest. It is responsible for compressing the abdominal viscera and the movement of the trunk by flexing and rotating. The fibers of the external oblique run inferomedially. In contrast to the external oblique, the internal oblique runs superomedially from the thoracolumbar fascia, anterior two-thirds, or iliac crest to the inferior borders of the tenth-twelfth ribs, linea alba, and pectin pubis via the conjoint tendon. It supports abdominal viscera and has minimal movement responsibility. The transversus abdominis muscle originates on the internal surfaces of the 7th to 12th costal cartilages, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, and lateral third inguinal ligament to the linea alba. Its main function is to compress the abdominal viscera. The fibers run horizontally. Then the rectus abdominis is the major flexor of the trunk. It also stabilizes and controls the tilt of the pelvis. Its origin is the pubic symphysis and crest; it then runs superiorly to the xiphoid process and the fifth to seventh costal cartilages. There is also a small muscle called the pyramidalis that is absent in 20% of the population. It lays at the inferior rectus abdominis and is responsible for tensing the linea alba.

Physiologic Variants

There are many variations of anatomy in the general population. Failure of the anterolateral abdominal wall to form leads to infants born with "prune belly syndrome." These infants have no musculature in their abdominal wall to help compress the internal viscera and flex the trunk. They often have undescended testes accompanied by urogenital malformations. These children undergo multiple surgeries to reconstruct the abdominal wall to support internal organs, improved respiratory effort, and cosmetic improvement.

Weakness in the abdominal wall can lead to a variety of hernias. The linea alba may also thin and spread laterally to form a weakened portion of the anterior wall, resulting in an outpouching when there is increased intra-abdominal pressure, also known as diastasis recti. As mentioned previously, the pyramidalis is absent in up to 20% of the population.

Surgical Considerations

Hernias may be found throughout the abdominal wall. The inguinal hernias are commonly a weakness either in the internal ring leading to the inguinal canal or the anterior abdominal wall medial to the inferior epigastric vessels. The weakness in the internal ring, formed by the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle, may lead to the formation of an indirect hernia. Peritoneal contents will protrude through the inguinal canal, and in severe or emergent cases, become strangulated, requiring emergency surgery. If the bowel contents protrude directly through the abdominal wall without traveling the inguinal canal, it is considered a direct hernia. If a hernia occurs along the semilunar lines, located laterally to the rectus abdominis, these are called Spigelian hernias. The umbilicus has a naturally weaker area of the fascia where the umbilical cord once emerged. This weakness may become even weaker with obesity, pregnancy, or any other cause of increased abdominal pressure leading to an umbilical hernia. Although diastasis recti is a widening of the linea alba with a sausage-like protrusion when the patient sits up, it is not a true hernia and does not need surgical intervention.[6][7]

Clinical Significance

Hernias may lead to incarcerated bowel or strangulated bowel if the contents can no longer be reduced through the defect resulting in decreased blood supply to the bowel. If the strangulation is not corrected immediately, the bowel contents may become necrotic, and the patient can become septic. Nonreducible or symptomatic hernias must be surgically corrected promptly so that necrosis of the contents may be avoided. Patients with prune belly syndrome must undergo multiple surgical procedures to help the patient improve respiratory effort, digestion, and proper function of the urogenital tract.