Histology, Alveolar Cells

- Article Author:

- Josiah Brandt

- Article Editor:

- Pujyitha Mandiga

- Updated:

- 4/29/2020 11:37:59 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Histology, Alveolar Cells CME

- PubMed Link:

- Histology, Alveolar Cells

Introduction

Alveoli represent the major sites of gas exchange. Their presence increases the surface area of the lung to maximize gas exchange, much like villi and microvilli increase the absorptive surface area of the digestive tract. For alveoli to carry out their function efficiently, they must be both a dynamic and stable system. The lung parenchyma must be able to expand and recoil during inspiration and expiration, and the air-blood barrier must be thin to allow for gas exchange to occur. Also, cells of the alveoli must be healthy to form a barrier to keep the lungs dry and be able to regenerate if they are damaged.

Structure

Alveoli represent the most distal portion of the respiratory tract. There are approximately 500 million alveoli in the human body. [1] Each alveolus is separated from each other by an alveolar septum, which contains the pulmonary capillaries participating in gas exchange and connective tissue. Each alveolus consists of three types of cell populations:

- Type 1 pneumocytes

- Type 2 pneumocytes

- Alveolar macrophages

Type I pneumocytes cover 95% of the internal surface of each alveolus. These cells are thin and squamous, ideal for gas exchange. They share a basement membrane with pulmonary capillary endothelium, forming the air-blood barrier where gas exchange occurs. These pneumocytes joined one another and other alveolar cells by tight junctions, forming an impermeable barrier to limit the infiltration of fluid into the alveoli.

Type II pneumocytes are much less prevalent in each alveolus, found in between type I pneumocytes. These cells are large and cuboidal with apical microvilli. Within their cytoplasm are characteristic lamellar bodies containing a surfactant, a substance secreted that decreases the surface tension of alveoli.

Alveolar macrophages are mononuclear phagocytes that are residents in alveoli. They derive from blood monocytes. The cell membrane of these cells can utilize a network of microtubules to change shape during chemotaxis or phagocytosis.[2]

Function

Type I pneumocytes have three main functions.

- Facilitate gas exchange

- Maintain ion and fluid balance within the alveoli

- Communicate with type II pneumocytes to secrete surfactant in response to stretch.

Type II pneumocytes have four main functions.

- Produce and secrete pulmonary surfactant - surfactant is a vital substance that reduces surface tension, preventing alveoli from collapsing

- Expression of immunomodulatory proteins that are necessary for host defense

- Transepithelial movement of water

- Regeneration of alveolar epithelium after injury [3][4]

Alveolar macrophages play an essential role in our immune system. They collect inhaled particles from the environment, such as coal, silica, and asbestos, and microbes, including viruses, bacteria, and fungi. Alveolar macrophages have a receptor named toll-like receptor, which binds to another receptor on the surface of microbial cells, the pathogen-associated molecular receptor. This interaction facilitates the phagocytosis of the pathogen along with the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines to enhance the local immune response. Within the alveolar macrophage, engulfed microbes become fused with its lysosome to destroy the pathogen.[2]

Tissue Preparation

H&E staining is the most common way to observe lung tissue. Samples are fixed and embedded in paraffin, then cut at 4 to 5 micrometers and mounted on glass slides. Sections are deparaffinized by two successive xylene baths, hydrated through decreasing alcohol concentrations, stained in Mayer’s hematoxylin solution, counterstained in 1% eosin Y solution, and finally observed under an optical microscope.

- Cytoplasm stains pink

- Nuclei stains blue

Trichrome staining can be useful to visualize collagen deposition in lung tissue. Samples are deparaffinized and rehydrated as the initial process of H&E staining described above. Then the tissue is stained in Weigert’s iron hematoxylin.

- Collagen appears blue

- Cytoplasm appears pink

- Nuclei are dark brown to black.

Immunofluorescent staining using antibodies specifically binding to their target proteins is a way to visualize the expression and localization of specific proteins of interest. In this method, the lungs are filled with optimum cutting temperature compound and frozen. They are cut at 5 to 10 micrometers, mounted on slides, and stored in a freezer at -70 degrees Celsius. Cells are covered with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes to permeabilize them if staining for proteins intracellularly.

- Incubation with diluted primary antibodies for 60 minutes at room temperature

- Fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies added for 60 minutes at room temperature.

- DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) added to stain DNA blue [5]

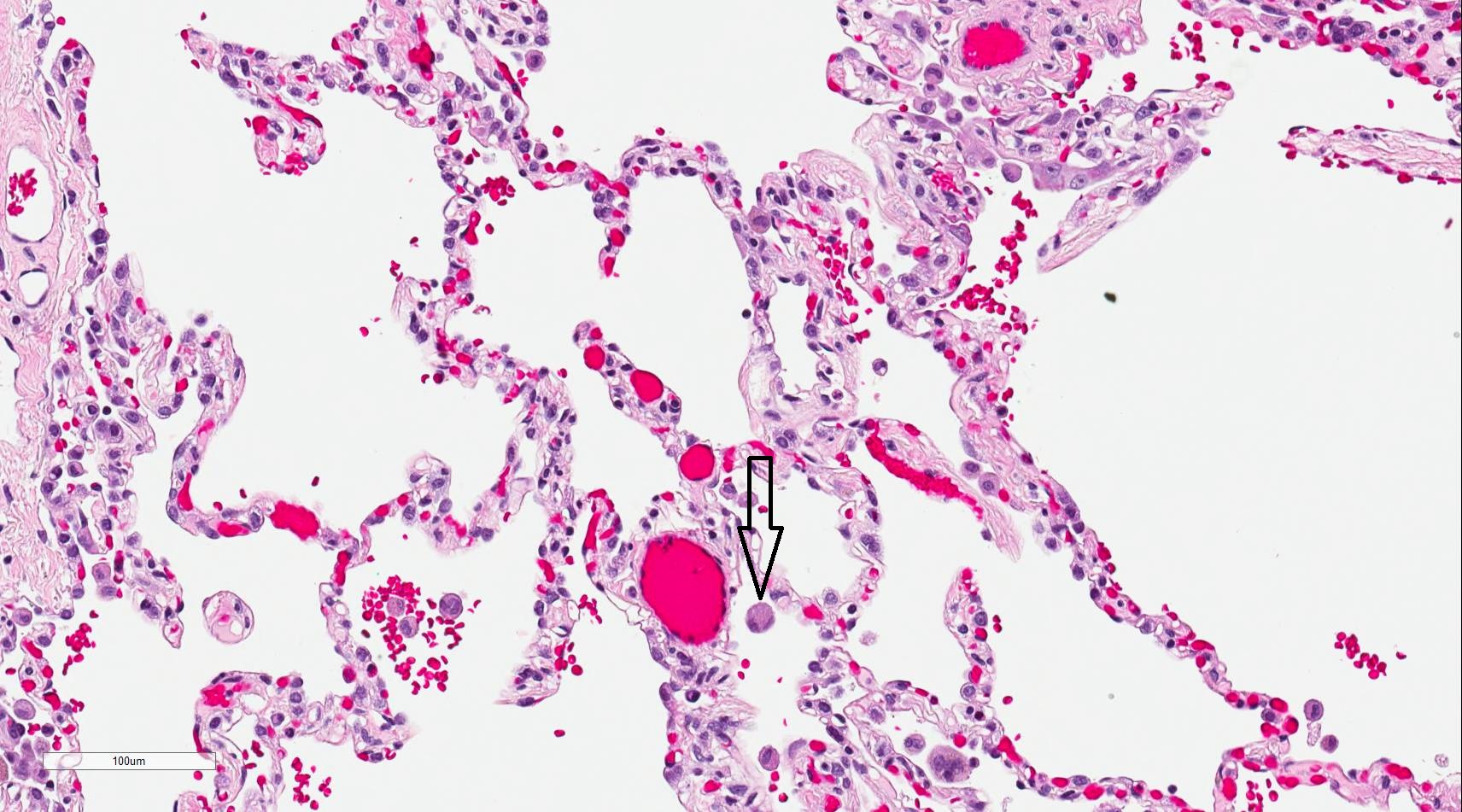

Carbon staining may help to visualize alveolar macrophages. Carbon is injected into the specimen then engulfed by alveolar macrophages, which can be visible as a dark accumulation within the cytoplasm of the alveolar macrophages.[2]

Histochemistry and Cytochemistry

HT156 is an alveolus protein specific to type I pneumocytes. It is on the apical plasma membrane. It can serve to target these cells to monitor for alveolar epithelium disease progression.[6]

Surfactant-associated proteins, CD44v6 expressed on the basolateral membrane, pepsinogen C (a protease), lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 3, and E-cadherin can all be found on or within the type II pneumocytes. HTII-280 has as an apical membrane integral protein specific to type II pneumocytes.[7]

Alveolar macrophages contain CD11b and CD68, which are possible markers for alveolar macrophages. In one study, there was an increased percentage of CD63, CD204, or CD206 markers within the lungs of patients with COPD versus nonsmokers and smokers.[2]

Microscopy Light

Using light microscopy to observe the histology of alveoli sections, type I pneumocytes are visible occupying a majority of each alveolus. These cells are flattened and squamous.

Occasionally within the alveoli, one can typically see type II pneumocytes. They are not as abundant within the alveoli. These cells are large and cuboidal or round and mostly concentrated in the alveoli septum. Granules containing surfactant are visible within the cytoplasm.

Visual examination also reveals alveolar macrophages within the lumen of the alveoli. These cells are round and can be larger than type II pneumocytes. They have an indented nucleus with granules within their cytoplasm.

Microscopy Electron

On electron microscopy, there is much more appreciation for the complex architecture of the alveoli. Type I pneumocytes are thin (<0.1 micrometers). They have a central nucleus and have thin extensions of the cell membrane called leaflets that cover the capillaries. The leaflets have an apical and basal membrane and connect to adjacent cells’ leaflets via tight junctions. The cytoplasm within the leaflets contains cytoskeletal fibrils, microtubules, and membrane vesicles for transcellular transport. The fused basal laminae of the type I pneumocyte and the capillary endothelial cell can be appreciated when observed under EM.

Type II cells are large and cuboidal. They have a large central nucleus with cytoplasm containing multilamellar bodies that are the factories of the protein-surfactant. They are connected to neighboring cells by intercellular and tight junctions. Microvilli are also visible as thin projections protruding from the apical surface of these cells.[8]

Under EM, alveolar macrophages are viewable; these contain nucleoli within a nucleus, ribosomes, Golgi bodies, mitochondria, and importantly lysosomes. These help the alveolar macrophages play its crucial role in supporting our immune system by fusing with engulfed microbes to destroy them.[2]

Pathophysiology

COPD (chronic bronchitis and emphysema)

COPD is a chronic and irreversible obstructive respiratory disease characterized by a reduction in the elasticity of the lungs, leading to air trapping and symptoms, including difficulty breathing. COPD is most commonly caused by smoking, which leads to the loss of alveolar epithelial cells, alveolar macrophages, and endothelial cells via apoptosis. When alveolar macrophages become disrupted, they are unable to phagocytize bacteria, leading these patients to have increased susceptibility to pulmonary infections. Additionally, alveolar macrophages release high levels of cytokines that promote inflammation, leading to the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes that also damage the lung via inflammation.[9][10]

Asthma

Asthma is another chronic obstructive respiratory disease, but in contrast to COPD, it is reversible. This disease characteristically demonstrates airway hyperreactivity and inflammation. Alveolar macrophages are responsible for regulating pro- and anti-inflammatory responses in the lungs, so it may be possible that these cells play a role in asthma.[11][12]

Cystic fibrosis

CF is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by the dysfunction of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) located on type II pneumocytes and in other areas of the body. The CFTR protein is responsible for the production of sweat production, digestive fluids, and mucous. Specifically, in the lungs, loss of function of the CFTR protein causes mucous lining the alveoli to become thick instead of thin. Additionally, there is an increased number of alveolar macrophages leading to an upregulation of inflammation. Thick mucus and inflammation clogs the airways and can cause difficulty breathing, coughing, and pulmonary infections to occur.[13]

Pulmonary fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis is a restrictive disease of the lower airway characterized by fibrosis and inflammation of the alveoli. Autoimmune or allergic reactions, environmental particulates, infection, or mechanical damage can initiate this disease process, starting with pulmonary injury. After the initial insult, inflammation in the airways results. Subsequent tissue repair and contraction leads to fibrosis and reduced ability to expand alveoli. In an attempt to replace damaged alveolar epithelium, type II pneumocytes become hyperplastic and proliferate and differentiate chaotically.[3][14]

Pneumoconioses

Pneumoconioses are interstitial lung diseases caused by the inhalation of organic and inorganic particles that are phagocytized by alveolar macrophages. Subsequently, they secrete cytokines that cause inflammation in the lungs. This process leads to particular diseases, such as coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, silicosis, and asbestosis. When alveolar macrophages engulf asbestosis, it is referred to as ferruginous bodies within the cytoplasm, which appear dumbbell-shaped.[2]

Tuberculosis

TB occurs when alveolar macrophages phagocytize the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis. M. tuberculosis has developed ways to avoid being destroyed once phagocytized and accumulate within alveolar macrophages. Also, alveolar macrophages attempt to wall off the infection by encircling it, forming multinucleated giant cells (or Langerhans giant cells). Surrounding them are T-cells, and it’s the communication between the alveolar macrophages and the T-cells via TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma that form a granuloma. It is important to note that damage to these alveolar macrophages caused by another infection can trigger the release of M. tuberculosis and cause recurrent tuberculosis.[2]

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoid is a condition that forms non-caseating granulomas in the lungs of patients by the joining of alveolar macrophages in an attempt to wall off the infectious process. Alveolar macrophages in sarcoidosis also secrete vitamin D, which contributes to the hypercalcemia seen in this disease.[2]

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

ARDS is characterized by non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema caused by some inflammatory condition that causes capillary endothelial leakage. The fluid eventually resolves, but some patients may develop residual fibrous tissue.[15] In infant respiratory distress, premature infants cannot overcome the collapsing surface tension of their alveoli because their type II pneumocytes have not been able to secrete surfactant fully.

Bronchioloalveolar or alveolar carcinoma of the lung accounts for about 5% of lung cancers. In addition to bronchial mucous cells and Clara cells, alveolar carcinoma can arise from type II pneumocytes as well.[16]

Left-sided congestive heart failure leads to the back up of blood within the pulmonary vasculature. When this happens, erythrocytes can pass into the alveolar septum, where they are taken up by alveolar macrophages, which become filled with hemosiderin. When looking at these cells under the microscope, they take on a brown granule appearance due to the hemosiderin within the cytoplasm of these cells. The name for these cells is hemosiderin-laden macrophages.[17]

Influenza pneumonia results from the influenza virus directly infecting alveoli epithelial cells, causing inflammation and alveoli damage. Alveolar macrophages play a role in protecting these pneumocytes from injury by the influenza virus.[18]

Clinical Significance

Alveolar cells are often observed in biopsy samples using needle, transbronchial, thoracoscopic, or open techniques. H&E, trichrome, immunofluorescent, and carbon staining methods are useful in identifying specific pathologies within samples. Light and electron microscopy are also diagnostic options.[19]

Alveoli are affected by several pathologies. In summary, these include chronic obstructive respiratory diseases, fibrosis, bacterial infections, viral infections, sarcoidosis, pneumonia, and carcinomas. Left-sided congestive heart failure and various inflammatory conditions can also lead to alveolar damage.