Physiology, Motor Cortical

- Article Author:

- Derek Yip

- Article Editor:

- Forshing Lui

- Updated:

- 9/20/2020 10:05:59 AM

- For CME on this topic:

- Physiology, Motor Cortical CME

- PubMed Link:

- Physiology, Motor Cortical

Introduction

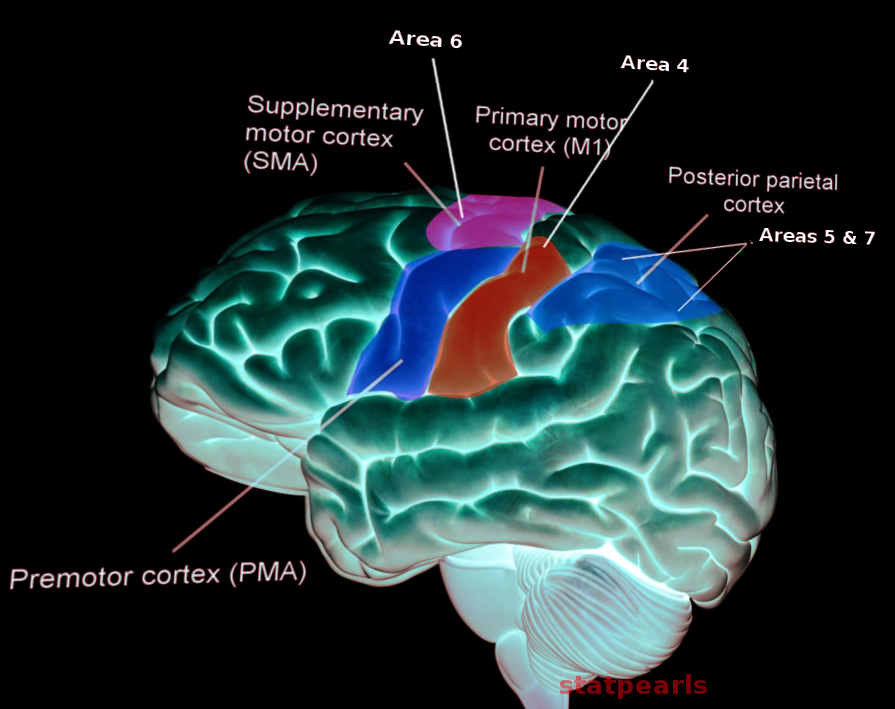

The primary function of the motor cortex is to generate signals to direct the movement of the body. It is part of the frontal lobe and is anterior to the central sulcus. It consists of the primary motor cortex, premotor cortex, and the supplementary motor area.[1] Not all parts of the motor cortex have the granular cell layer. The primary motor cortex, situated in Brodmann area 4, sends most electrical impulses coming out of the motor cortex. These fibers directly synapse with motor neurons of the spinal cord. It is worth noting that corticospinal fibers originate both from the frontal cortex and also the parietal cortex. Anterior to the primary motor cortex, the premotor cortex is situated just anterior to the primary motor cortex in Brodmann area 6. Its function is to prepare for movement, especially proximal musculature. The supplementary motor area is in the medial surface of the longitudinal fissure, just anterior to the leg representation in the primary motor cortex. Although not fully understood, proposed functions include body postural stabilization and coordination.[2]

There are important differences in the cortical projections from the cortical motor neurons. Those fibers originating from the primary motor cortex (area 4) terminate mainly in the spinal cord, synapsing directly on motor neurons. The rostral frontal motor areas do not terminate directly at the spinal cord. They send fibers that terminate in various areas of the brainstem. Therefore they control movements indirectly through the brainstem such as the tectospinal and reticulospinal tracts. It is also more understandable that they will control more the proximal and axial muscles and movements.

Cortical afferents to the frontal motor cortex arise from three sources: the parietal somatosensory cortex, the prefrontal cortex, and the cingulate cortex. The parietal-frontal connections represent different sensory-motor circuits. The cingulate cortex sends fibers to the premotor and supplemental motor areas for limbic information, motivation, and decision. Finally, the prefrontal cortex sends fibers to the motor cortex serving important functions of motor planning and execution.

Issues of Concern

Weakness and paralysis resulting from motor cortex dysfunction can significantly reduce the quality of life in patients. Fortunately, some risk factors for stroke can be mitigated, such as hypertension, smoking, diabetes, poor diet, high cholesterol, and physical inactivity. It is crucial that health care practitioners counsel patients regarding these factors prevent serious neurologic harm.[3]

Cellular

At the cellular level, the neuron is responsible for communication across the motor cortex. The neuron is composed of three main parts: dendrites, soma, and axon — other neurons signals which are received by the dendrites. The dendrite then transmits this signal to the cell body or soma. The soma contains the nucleus and axon hillock. The nucleus is responsible for creating all proteins and membranes that keep the neuron alive. The axon hillock is where the action protentional gets transmitted to the axon. The axon then delivers the action potential to the axon terminals, which synapse with the dendrites of other neurons. The motor cortex has somas that generate action potentials down to the spinal cord; this is called the upper motor neuron. The upper motor neuron communicates with the lower motor neuron via glutamate.[4] The motor cortex has only a rudimentary layer IV, which functions to receive thalamocortical projections. Therefore these areas are also called the agranular cortex with no input from the thalamus.

Development

After three weeks of development, the nervous system divides into three primary brain vesicles: the forebrain (prosencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon), and hindbrain (rhombencephalon). The nervous system then becomes a five-vesicle stage with the forebrain splitting into the cerebral hemispheres, thalamus, and hypothalamus. Following the formation of the different regions of the brain, there is a proliferation of neurons and migration of these neurons from the periventricular zone to the cortex in an inside out manner to its final 6-layered cortical cytoarchitecture. The upper motor neurons originate from layers 5 and 6 of the cerebral hemispheres, specifically the primary motor cortex.[5]

Organ Systems Involved

The musculoskeletal system relies on the motor pathway to command it. At the neuromuscular junction, the lower motor neuron synapses with the muscle fiber. After the action potential reaches the axon terminal of the lower motor neuron, voltage-gated calcium channels open to increase intracellular calcium ion concentrations, which allows vesicles of acetylcholine to fuse with the membrane and be released into the synaptic cleft to produce muscle contractions.

Function

The primary function of the motor cortex is to plan and create electrical impulses that cause voluntary muscle contractions. The nerves that come out of the motor cortex can be either cranial nerves or spinal nerves. Cranial nerves come directly from the brainstem, whereas spinal nerves emerge from the spinal cord. There are several cranial nerves (CN) that have a motor function, including CN III (oculomotor nerve), CN IV (trochlear nerve), CN V (trigeminal nerve), CN VI (abducens nerve), CN VII (facial nerve), CN IX (glossopharyngeal nerve), CN X (vagus nerve), and CN XI (accessory nerve) and CN XII (hypoglossal nerve). CN III, CN IV, and CN VI are involved in eye movement. CN V innervates the muscles of mastication. CN VII allows movement of the facial muscles. CN IX innervates the stylopharyngeus muscle, which allows for movement of the pharynx and larynx. CN X has many functions that play a role in speaking and swallowing. CN XI is involved with shoulder shrugging and head-turning with innervation of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid, respectively. CN XII innervates most muscles of the tongue.[6]

Supplementary Motor Area

Primarily, the supplementary motor area projects to the motor cortex. It appears to be involved mainly in programming in motor sequencing. Any lesions of this area in monkeys produce awkwardness in performing complex activities with bimanual coordination.

When humans count to themselves without speaking, the motor cortex is quiescent, but when they count, the number out loud as they count, blood flow increases in the motor cortex and the supplementary motor area. Furthermore, the supplementary motor area, as well as the motor cortex, is involved in the voluntary movements when the movements being performed are complex and require planning. The blood flow increases whether or not a planned movement is carried out. The increase in blood flow occurs whether the movement is performed by the contralateral or the ipsilateral hand.[7]

Mechanism

Starting at the primary motor cortex, the upper motor neuron descends and passes through the ipsilateral posterior limb of the internal capsule. Most of the fibers will decussate at the pyramidal decussation at the caudal medulla. From here, the upper motor neuron is on the contralateral side of its origin. The upper motor neuron synapses with a lower motor neuron in the anterior horn of the spinal cord at the appropriate level. The lower motor neuron exits the spinal cord to synapse to a muscle.[8]

Related Testing

Testing for an intact motor cortical pathway can involve deep tendon reflex testing. The biceps (C5, C6), brachioradialis (C6), triceps (C7), patellar (L4), and Achilles tendon (S1) can be tested to assess intact nerve roots. When stretched, the muscle spindle sends a signal down the 1 alpha nerve fiber. The fiber enters the spinal column via the dorsal root and synapses onto a lower motor neuron and interneuron. The lower motor neuron will cause the agonist muscle to contract while the interneuron will cause the antagonist muscle to relax.[9]

Pathophysiology

Tetanus is a condition caused by the exotoxin tetanospasmin from Clostridium tetani. Tetanus causes painful muscle contractions, especially in the jaw and neck. Tetanospasmin inhibits the release of glycine and GABA, which are inhibitory neurotransmitters. Without inhibition of the skeletal muscles, sustained contraction occurs.

A stroke is when a portion of the brain does not receive sufficient blood. As a result, stroke symptoms can manifest as motor function deficits should parts of the motor cortex be infarcted. However, this often presents with other symptoms such as speech or vision deficits. A pure motor stroke is possible and is symptomatic of a lacunar stroke, causing infarct of the posterior limb of the internal capsule. This infarct can present with hemiparesis, which is a weakness of one side of the body.[10]

Clinical Significance

Damage to the motor cortex results in a clinical condition called upper motor neuron syndrome. It can also arise as a result of damage to the axons arising from the motor cortex, i.e., the corticospinal tract. Clinically there is the presence of weakness without significant muscle wasting, spasticity (increased muscle tone with clasp-knife rigidity), hyperreflexia, and positive Babinski sign. Babinski sign is a normal reflex in infants, but abnormal in adults. It occurs when the big toe moves upward after the sole stroked firmly.[11] Clasp knife rigidity or spasticity characteristically presents by an initial resistance in movement followed by a rapid decrease in resistance. Upper motor neuron lesions present with a pattern of weakness that is also typical with less weakness affecting the anti-gravity muscles. This pattern gives rise to the familiar appearance after a stroke with damage to the motor cortex. The patient will have a flexed posture in the affected upper extremity and extended posture in the lower extremity. The patient will walk with a typical hemiparetic gait. Lower motor neuron lesions arise from the damage of the motor neuron in the spinal cord and characteristically presents with weakness, atrophy, fasciculations, hyporeflexia, decreased tone, and flaccid paralysis.