Transabdominal Plane Block

- Article Author:

- Ana Mavarez

- Article Editor:

- Andaleeb Ahmed

- Updated:

- 7/28/2020 6:19:01 PM

- For CME on this topic:

- Transabdominal Plane Block CME

- PubMed Link:

- Transabdominal Plane Block

Introduction

Regional anesthesia for abdominal wall procedures can be performed using a variety of peripheral nerve blocks. These blocks are typically ultrasound (US) guided and involves injecting a local anesthetic (LA) solution into interfascial planes. US-guided transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block implicates the injection of LA in between the transversus abdominis (TA) and internal oblique (IO) muscles. The TAP block can also be targeted using anatomical landmarks at the level of the Petit triangle. This interfascial plane contains the intercostal, subcostal, iliohypogastric, and ilioinguinal nerves. These nerves give sensation to the anterior and lateral abdominal wall as well as the parietal peritoneum, providing only somatic and not visceral analgesia.

The TAP block can be for postoperative analgesia management in open and laparoscopic abdominal surgeries as well as inpatient and outpatient surgical procedures.[1] Unilateral left or right-sided blocks are used for unilateral surgical procedures, such as cholecystectomy, appendectomy, nephrectomy, or renal transplants, while bilateral TAP blocks are used for midline and transverse abdominal incisions, such as umbilical or ventral hernia repair, cesarean deliveries, hysterectomy, and prostatectomy. TAP blocks are part of multimodal pain management for abdominal surgeries, which adds analgesic benefit to the patients, reducing postoperative opioid requirements. TAP blocks are usually placed intraoperatively, either before surgical incision or at the end of the procedure before emergence from anesthesia. The efficacy of the TAP block is dependent on the spread of LA across the interfacial plane. Newer tissue plane blocks like quadratus lumborum block provide visceral analgesia in addition to somatic analgesia.

The TAP block has become one of the most common truncal blocks performed for postoperative analgesia after abdominal surgeries. This activity reviews the anatomy of the abdominal wall, history of the TAP block, classification, approaches, techniques, and complications for this block. It also highlights the indications, contraindications, clinical significance, and equipment to perform this block in a safe manner.

Anatomy and Physiology

Reviewing the anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall will result in a greater understanding of the neurovascular anatomy within the TAP block. The anterolateral abdominal wall has four muscles: the rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles. The TAP anatomical compartment is a plane that is located between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles and contains the T6–L1 thoracolumbar nerves.

The sensitive innervation of the anterolateral abdominal wall results from the spinal nerves, anterior rami. Immediately after exiting from their respective intervertebral foramina, spinal nerves divide into anterior and posterior rami. The anterior rami split into two branches, the anterior and lateral cutaneous nerves. The anterior cutaneous nerve from the T6–T11 segments gives rise to intercostal (IC) nerves, which supply sensitivity to the skin and muscles of the anterior abdominal wall. The T9–T11 IC and T12 subcostal (SC) nerves penetrate the transversus abdominis plane compartment posterior to the midaxillary line.

The lower thoracic intercostal and subcostal nerves innervate the skin of the infra-umbilical area between the midline and midclavicular lines.[2] L1 lumbar plexus gives rise to ilioinguinal (II) and iliohypogastric (IH) nerves. II and IH provide sensory innervation to the upper hip, groin, and thigh. Branches of all these nerves variably travel between the transversus abdominis (TA) and internal oblique (IO) muscles in the TAP compartment.

The first description of the transversus abdominis plane block is accredited to Rafi in 2001, who advocated the performance of this block by anatomical landmarks at the level of the lumbar triangle of Petit.[3] The Petit triangle edges are conformed by the iliac crest as the inferior edge, the latissimus dorsi as the posterior edge, and the external oblique as the anterior edge. The tip of the triangle is the rib cage.

Traditionally, these landmark blocks have blind endpoints (pops), making their success unpredictable. In 2006, O'Donnell introduced the term transversus abdominis plane block and modified Rafi's original description by advocating a double pop technique. In 2007, Hebbard et al. advocated the use of ultrasound guidance to identify the intermuscular planes and the use of the midaxillary line (lateral approach) instead of the triangle of Petit. In 2010 Lee et al. demonstrated that the subcostal approach covered an increased number of dermatomes (4 vs. 3 by the lateral approach) and yielded a higher sensory blockade (T8 vs. T10).[4][5][6]

Indications

Provide analgesia after an abdominal wall procedure in a variety of abdominal surgeries are the indications of the TAP block. The TAP block can be performed for open abdominal surgeries as well as laparoscopic procedures. The TAP block is an easier and less risky substitute for epidural anesthesia in postoperative pain control for abdominal surgeries.

- A unilateral block is used for a one-sided procedure, such as appendectomy, cholecystectomy, nephrectomy, and renal transplant.

- Bilateral blocks are used for midline and transverse abdominal incisions, such as ventral hernia repair, umbilical hernia repair, exploratory laparotomies, colostomy closures, cesarean delivery, hysterectomy, radical retropubic prostatectomy, bariatric surgeries, inguinal hernia repair, and laparoscopic surgeries.

Contraindications

This procedure is contraindicated in the following scenarios:

- Patient refusal

- Infection over the site of injection

- Allergy to local anesthetics

Caution should be maintained in patients that are on therapeutic anticoagulation, pregnant and, where anatomical landmarks are difficult to distinguish (like very thin patients, elderly, or deconditioned).

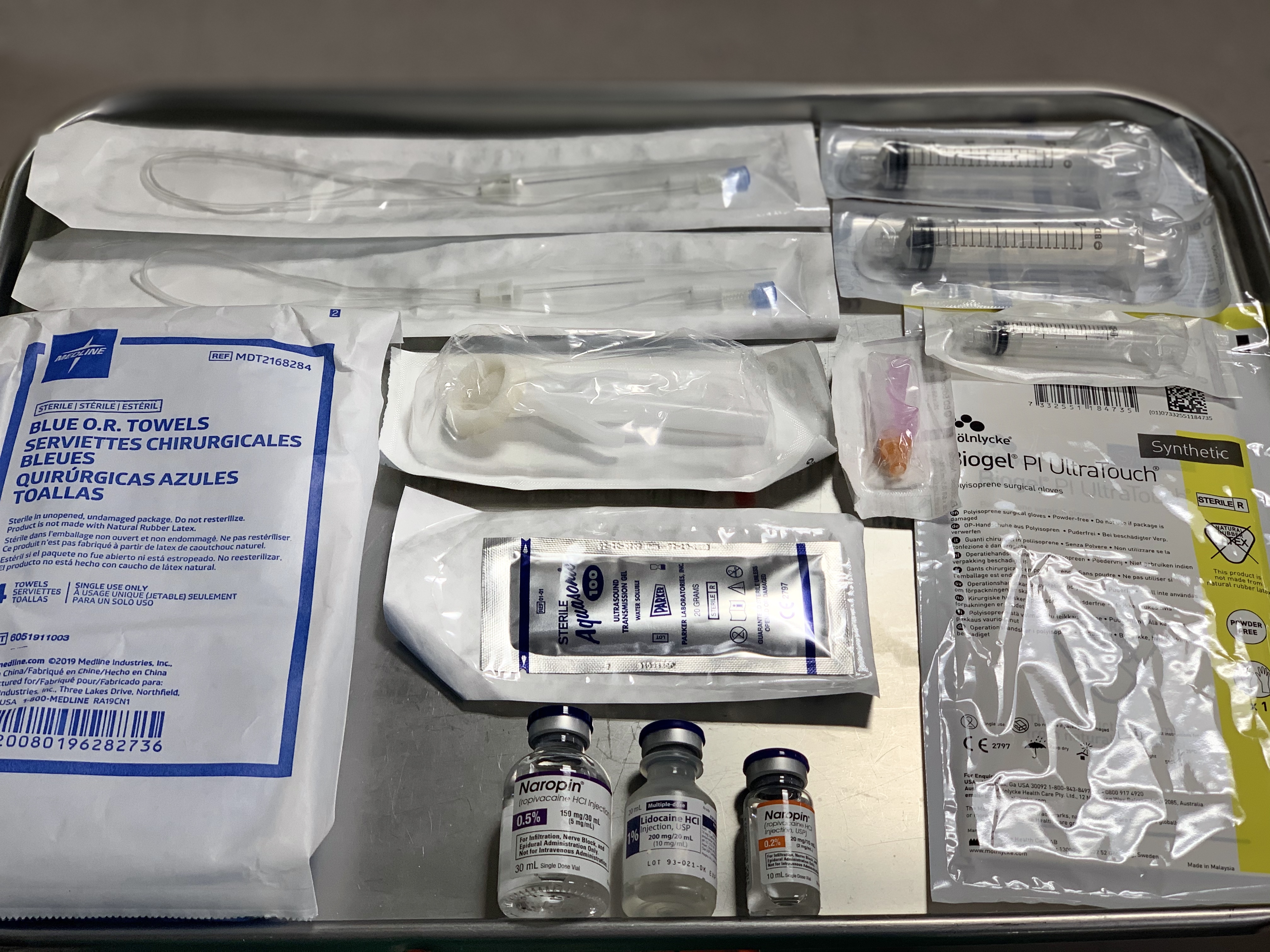

Equipment

The following are the necessary materials to perform a TAP block (Image 1):

- Ultrasound machine with a linear transducer. (Sometimes a curvilinear transducer might be needed, if the patient is obese or if performing a posterior approach)

- Sterile ultrasound probe cover sleeve

- Sterile ultrasound gel

- Sterile towels

- Sterile gloves

- Antiseptic for skin disinfection, such as chlorhexidine 2%

- Nerve block needle (50-mm to 100-mm, 20-gauge to 21-gauge needle) with tubing

- Two 20-mL syringes containing the local anesthetic solution

- Local Anesthetic Agent: Ropivacaine, Bupivacaine or Liposomal Bupivacaine

- One 5ml syringe containing lidocaine for skin local anesthesia (if the patient is awake)

- Basic physiological monitors: EKG, pulse oximeter and blood pressure monitor

- If performing the block in an awake patient: A 5-ml syringe with needle for skin infiltration with Lidocaine 1% local anesthetic

Personnel

The TAP block should be performed by a skilled medical provider with regional anesthesia training, such as anesthesiologists. A second healthcare provider or nurse is required to perform a pre-procedure time-out and to assist during the procedure with the ultrasound and for the injection of local anesthetic while the anesthesiologist positions the needle and directs when and how much to inject.

Preparation

Before performing a TAP block, the health care provider must:

- Obtain informed consent for the procedure, discussing the possible risks, benefits, and alternatives for pain management.

- The patient should have IV access before the procedure.

- The patient should be monitored using continuous EKG, continuous pulse oximetry, and blood pressure cuff cycling every 5 minutes.

- Position the patient supine and uncover the abdomen.

- Prepare the area with an antiseptic solution to clean the skin of the anterolateral area of the abdomen (from the costal margin to iliac crest)

- After prepping the area and let the antiseptic dry, place sterile towels surrounding the border of the procedural field

- A pre-procedural time-out should take place prior to starting the procedure, including name, medical record number, date of birth, allergies, the procedure that will be performed and, laterality.[7]

Technique

There are several TAP block techniques on how the TAP block compartment is identified:

- The original landmark-guided TAP block at the level of the Petit triangle (described above)

- The ultrasound-guided TAP block that can be found anatomically in the subcostal, lateral, and posterior approach

- The surgeon may perform a laparoscopic-guided TAP block visualizing from inside of the abdominal cavity and feeling 2 "pops" or loss-of resistance with the needle from outside of the abdomen during surgery.

The ultrasound-guidance technique is considered the gold standard in TAP blocks because it is easy for the operator to acquire ultrasound images and safe for the patient to perform the procedure under direct visualization of the needle before the injection of LA. For these techniques, the patient should be positioned supine for most of these approaches, except for slight lateralization for the posterior approach in some cases. A high-frequency linear or curvilinear ultrasound transducer should be used [5] and placed in the abdomen with gel for adequate contact and transmission of the ultrasound waves.

In the ultrasound image visualized (Image 5), the most superficial layer is skin and subcutaneous fat, then there are three muscular layers, from superficial to deep: external oblique, followed by the internal oblique, and lastly, the transversus abdominis muscle. The internal oblique muscle is usually the thickest muscle layer in the majority of patients, while the transversus abdominis muscle is the thinnest. If uncertain of the layer borders, increase the depth of the ultrasound to confirm bowel beneath the transversus abdominis muscle. Scanning posteriorly, the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles show the two layers come together to form the thoracolumbar fascia. Scanning medially, the aponeurosis of the three muscle layers come together to form the rectus sheath. Upon identifying the TAP compartment with the ultrasound probe, infiltrate the patient's skin using lidocaine (if the patient is awake), penetrate the skin with the block needle using an in-plane technique, making sure to visualize the needle tip on ultrasound throughout its entire trajectory. Upon entering the plane between the internal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscles, and after negative aspiration of blood, the LA is slowly injected. The TAP compartment will begin to separate, hydrodissect, or "unzip" as the LA is injected, pushing the transversus abdominis muscle down. Usually, an injection of 15 to 20 ml of LA is recommended for each side for an adult patient. The dose and volume depend on the patient's weight as well as the concentration of the LA. The spread of LA along the TAP compartment is responsible for the success of the block. Studies had shown that the efficacy of the block is improved when injecting 15 ml or more.[8]

There are three approaches for ultrasound-guided TAP block to target the compartment anatomically:

- Subcostal approach: Targets the TAP compartment in the anterior abdominal wall, beneath the costal margin. The high-frequency probe should be located in the lower margin of the rib cage between the xiphoid process and the anterosuperior iliac spine at the level of the anterior axillary line. The objective is to deposit the LA in the plane among the transversus abdominis muscle and the posterior rectus sheath. The needle should be inserted above the rectus abdominis muscle and advanced it until it is positioned between the anterior edge of the transversus abdominis muscle and posterior rectus sheath [2]. This area is covered by T6-T9 dermatomes, blocking the anterior cutaneous nerves. The anterior approach is used to provide analgesia for open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy surgeries. (Image 2)

- Lateral approach: Targets the TAP compartment in the lateral abdominal wall. The high-frequency probe should be located in the midaxillary line between the bony prominences of the subcostal margin and the iliac crest. The three muscular layers in the abdominal wall muscles should be visualized. The objective is to deposit the LA in the plane among the transversus abdominis muscle and the internal oblique muscle. The needle should be inserted and advanced until it reaches the TAP plane. This area is covered by T10-T12 dermatomes, blocking the anterior cutaneous nerves. The lateral approach is used to provide analgesia for most abdominal surgeries, including laparoscopic surgeries, open appendectomy, ventral hernia repair, umbilical hernia repair, exploratory laparotomies, colostomy closures, cesarean delivery, hysterectomy, bariatric surgery, and radical retropubic prostatectomy among others. (Image 3)

- Posterior approach: Targets the TAP compartment at the level of the lumbar triangle of Petit or the anterolateral aspect of the quadratus lumborum muscle. The high-frequency probe should be located in the midaxillary line and then displaced lateral and posteriorly to the end limit of the three muscular layers. The objective is to deposit the LA in the plane among the transversus abdominis muscle and the internal oblique muscle but in the posterior end limit of the TAP plane.[1] The needle should be inserted in the midaxillary line and advanced posteriorly until it reaches the TAP plane. This area is covered by T9-T12 dermatomes, blocking the anterior and lateral cutaneous nerves. The posterior approach is used to provide analgesia for nephrectomies, renal transplants, and others. (Image 4)

Other blocks:

TAP block vs. Rectus Sheath Block: The rectus sheath block targets the compartment between the rectus abdominis muscle and the posterior rectus muscle sheath. The high-frequency probe should be placed in a transverse orientation below the costal margin on the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle at the upper 1/3 of the rectus muscle, where the transversus abdominis muscle extends medially and provides a layer of safety between the compartment and the peritoneum to prevent peritoneal injection of LA. In the ultrasound image should visualize the rectus muscle, the posterior rectus sheath, and the transversus abdominis muscle below the rectus sheath. The LA should separate the sheath from the muscle body, the rectus muscle should be displaced upward, and the transversus abdominis muscle downward. The LA should extend in both directions, cephalad and caudal, within the sheath. The rectus sheath block is used to provide analgesia for midline vertical or paramedian abdominal incisions such as exploratory laparotomy incision, umbilical surgeries, and for umbilical port incisions for laparoscopic surgery.

TAP block vs. Ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric block: The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric block targets these two nerves that are located within the TAP compartment above the inguinal ligament. The high-frequency probe should be placed cephalad and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) in the direction of a line between the umbilicus and the ASIS. Get the US picture of the three layers of abdominal muscles. In the TAP compartment may or may not be visible the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves as echogenic structures along with the deep circumflex iliac artery. This is a block that requires less volume of LA, approximately 5 to 10 ml. The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric block is used to provide analgesia for inguinal hernia surgeries.

TAP block vs. Quadratus Lumborum block: The quadratus lumborum (QL) block targets the fascial plane in the posterior surface of the QL muscle. There are three types of QL blocks, and each one targets a fascial plane defined by different muscles. Compared to the TAP block, the QL block covers more dermatomes with better cephalad and posterior spread. QL blocks provide both visceral and somatic analgesia, probably due to paravertebral and epidural spread. For this block, a curvilinear probe should be located in an axial position at the level of the umbilicus and the anterior axillary line. Visualize the three layers of abdominal muscles and trace laterally until the internal oblique muscle and the transversus abdominis muscle merge, becoming the transversalis fascia (TF). The QL muscle is deep to the transversalis fascia. The fascia extends posteriorly as the thoracolumbar fascia (TLF). The needle should be inserted in-plane with the curvilinear probe at the level of the posterior axillary line in between the costal margin and the iliac crest bony prominences.

- The QL1 block targets the superficial anterolateral corner of the QL muscle, where the TF meets the QL muscle; after injection of LA, the QL muscle should displace downwards. This block covers T12-L1 dermatomes only, blocking the subcostal, iliohypogastric, and ilioinguinal nerves. The QL1 block is used to provide analgesia for abdominal surgeries below the umbilicus.

- The QL2 block targets the superficial posterolateral corner of the QL muscle, posterior to the QL muscle but outside the middle layer of the TLF; after injection of LA, the QL muscle should displace downwards. This block covers the area from T4 to T12-L1 dermatomes, blocking the anterior and lateral cutaneous nerves. The QL2 block is used to provide analgesia for abdominal surgeries either above or below the umbilicus.

- The QL3 block targets the compartment between the QL muscle and the psoas major muscle. The needle should go through the QL muscle, and it is also called transmuscular QL block; after injection of LA, the QL muscle and psoas muscle should hydrodissect and separate. This block covers the area from T4 to T12-L1 dermatomes, blocking the anterior and lateral cutaneous nerves. The QL2 block is used to provide analgesia for abdominal surgeries either above or below the umbilicus.

Complications

Complications related to TAP blocks are rare. Some complications have been reported in the literature, including:

- Bowel perforation

- Hematoma

- Liver/Spleen laceration

- Intrahepatic injection

- Intraperitoneal injection of local anesthetic

- Retroperitoneal hematoma due to vascular injury

- Transient femoral nerve blockage

- Local infection

- Intravascular injection

- Local Anesthetic systemic toxicity

It is recommended to utilize ultrasound guidance rather than anatomical landmarks to increase the success rate and minimize these complications. There have been minimal reported complications after the universal implementation of the ultrasound-guided technique for the TAP block.[9]

Neurological injury is rare in TAP blocks, because these are field blocks, relying on the high volume of the local anesthetic injected to facilitate adequate blockade of the nerves that are located in the compartment, rather than targeting a specific nerve. If a neurologic injury occurs might be from direct nerve trauma from the needle, hematoma, or local infection. Excessive needle insertion, especially in thin, elderly, or deconditioned patients may also lead to complications such as visceral trauma, vascular injury, intraperitoneal injection, or intrahepatic injection.[10]

Case reports have also described transient femoral nerve palsy where some of the local anesthetic injected for the TAP block could trail on the fascia iliaca below the inguinal ligament, producing an inadvertent blockage of the femoral nerve. If this incident happens, the surgical team should be made aware and the patient has to be advised regarding the potential risk for falls.[11] LA injection within the TAP block is within an interfascial plane that is well vascularized, the reason why the operator should perform careful aspiration before injecting a local anesthetic to avoid an accidental vascular puncture and intravascular injection that might lead to local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) which is a rare but known complication for the TAP block.

Clinical Significance

With the advent of US-guidance, there has been a surge in popularity for the TAP block, now beingly highly used for postoperative analgesia management following abdominal surgery. The TAP block is used as part of the multimodal analgesia management for abdominal surgeries that include the use of at least two non-opioid analgesic agents (e.g., acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, gabapentinoids, IV lidocaine, ketamine or local anesthetic wound infiltration) in addition to oral or parental opioids.

The benefits of the TAP block includes a reduction in opioid requirements in the postoperative period and a decrease in postoperative nausea and vomiting, but no difference in visual analog pain scale scores.[12] The TAP block has become an important addition to the clinicians because of its safety profile, ease to perform, effectiveness for pain control in a multimodal pain management approach with an increase in patient satisfaction, and in reducing the contribution to the world opioid crisis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A multidisciplinary team approach is essential to perform regional anesthesia blocks, including the TAP block.

- The informed consent should be ethically obtained beforehand by the health care provider, who should explain to the patient the risks, benefits, alternatives, possible side effects, and complications of the TAP block.

- An appropriate time-out has to be performed before the start of the procedure. This should be done by the nurse with the presence of the anesthesiologist, surgeon, if possible, OR personnel, and patient listening if awake. The time out should consist of confirming out loud the patient's name, medical record number, date of birth, allergies, block to be performed, laterality, and dose/amount of LA to be injected (especially for pediatric patients).

- The team-based proposal must consist of the surgeon, anesthesiologist, nurses, pharmacist, surgical assistant, and the rest of the OR personnel.

- It is very important to maintain interpersonal communication with all the team members, especially with the surgeon to evaluate the suitability of the block that we are planning to perform, the location and size of the incision and, discussions about when performing the block before induction of anesthesia (with an awake patient) after induction or before emergence. After the block is performed, it is imperative to notify the surgeon and all the team members how much LA was injected to avoiding extra local infiltration of LA by the surgeon to prevent an episode of LAST and enhance patient safety.

- The pharmacist will prepare the local anesthetic concentration and dose as the clinician ordered, ensure providing a safe-dose below the maximal dose per weight, have intralipid emulsion available in case the LAST episode, and being available if there are any medication-related questions by the team.

- Nurses will perform the pre-procedure time-out and assist during the procedure (additional nursing duties are outlined below).

- If the block is going to be done on an awake patient, the patient should be aware of the possible sensations he/she might feel, and the operator should maintain verbal contact with the patient at all times throughout the procedure, to monitor any complications such as potential nerve injury, visceral perforation, or LAST. During the procedure, patient vital signs should be monitored in real-time.

- The operator and assistance should take extreme caution when handling sharps one another as accidental needle sticks may occur. Disposal of needles should be done in designated sharp-bins in the procedure area.

- Documentation of the procedure should include informed consent, date, time, procedure location, block technique, LA used, volume and concentration of injectate, equipment used, ultrasound images, and documentation of any complication.

Following all these measurements will enhance patient care, improve the procedure outcomes, patient safety, and will enhance team performance.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The nurse is very important for the successful performance of the TAP block. Their interventions include:

- Verify that the patient signed the inform consent for the procedure

- Verify the side of the procedure (if unilateral) that is the correct side of the abdomen

- Setting up the ultrasound, syringes, needles, medications, and all equipment necessary to perform the block

- Placing all the monitors pre-procedure (EKG, pulse oximetry and blood pressure monitors)

- Positioning and preparing the patient for the procedure

- Performing the pre-procedure time-out

- Assisting the operator if needed during the procedure

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

The nurse should be available before, during, and after the TAP block to monitor the patient, including:

- Verify that pre-procedure, a crash car is close and available with resuscitative equipment in it.

- Monitor the patient vital signs and clinical status during and after the procedure.

- After the procedure when in the recovery room, the nurse should assess the patient's block site for bleeding, hematoma, or abdominal distension.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)