Adamantinoma of long bones

| Adamantinoma of long bones | |

|---|---|

| |

| X-ray (side and front views) showing an adamantinoma in the large bone of lower leg, near the ankle. | |

| Specialty | Oncology, orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Swelling, with or without pain in the lower leg[1] |

| Diagnostic method | X-ray, MRI[2] |

| Treatment | Surgery[3] |

| Frequency | Rare, 0.4% of primary bone tumors[2] |

Adamantinoma of long bones is a cancerous bone tumor, that almost always occurs in the bones of the lower leg.[2] Swelling over the affected bone with or without pain are the most frequent clinical features.[1]

X-rays of the affected area show a well defined tumor in bone, with multiple lobules giving a "soap bubble" appearance.[2] MRI can provide a more useful guide to its severity.[2]

Treatment is by surgically removing the tumor.[3]

The condition is rare and accounts for around 0.4% of bone tumors that arise from bone.[2] It was first described by Fischer in 1913.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Swelling over the affected bone with or without pain are the most frequent clinical features. The slow-growing tumor predominantly arises in long bones in a subcortical location (95% in the tibia or fibula).[1]

Benign osteofibrous dysplasia may be a precursor of adamantinoma[5][6] or a regressive phase of adamantinoma.[7]

Diagnosis

X-rays of the affected area show a well defined tumor at the edge of the bone, with multiple lobules giving a "soap bubble" appearance.[2] MRI can provide a more useful guide to its severity.[2]

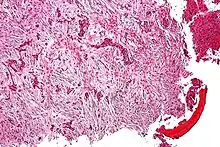

It involves both epithelial and osteofibrous tissue.[1] Histologically, islands of epithelial cells are found in a fibrous stroma.[8]

Treatment

Treatment is by surgically removing the tumor.[3] Sometimes an amputation is needed.[8]

Outcomes

Metastases are rare at presentation but may occur in up to 30% of people during the disease course. Prognosis is excellent, with overall survival of 85% at 10 years, but is lower when wide surgical margins cannot be obtained. This tumor is insensitive to radiation so chemotherapy is not typically used unless the cancer has metastasized to the lungs or other organs.[8]

Epidemiology

The condition is rare and accounts for around 0.4% of bone tumors that arise from bone.[2][4] Most commonly, people are aged 25 to 35 years, but it has been reported in ages 3 - 86 years of age.[2]

Spread to lungs or lymph nodes can occur in 12%-29% of people with adamantinoma.[3]

History

The typically benign odontogenic tumor known as ameloblastoma was first recognized in 1827 by Cusack but did not yet have any designation.[9] In 1885, this kind of odontogenic neoplasm was designated as an adamantinoma by Malassez[10] and was finally renamed to the modern name ameloblastoma in 1930 by Ivey and Churchill.[11][12] Some authors still confusingly misuse the term adamantinoma to describe ameloblastomas, although they differ in histology and frequency of malignancy.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Jain D, Jain VK, Vasishta RK, Ranjan P, Kumar Y (2008). "Adamantinoma: A clinicopathological review and update". Diagn Pathol. 3: 8. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-3-8. PMC 2276480. PMID 18279517.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "Adamantino of long bones". Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 3 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. pp. 463–466. ISBN 978-92-832-4503-2. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- 1 2 3 4 Limaiem, Faten; Tafti, Dawood; Malik, Ahmad (2021). "Adamantinoma". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- 1 2 "Adamantinoma: Overview - eMedicine". Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ↑ Hatori M, Watanabe M, Hosaka M, Sasano H, Narita M, Kokubun S (May 2006). "A classic adamantinoma arising from osteofibrous dysplasia-like adamantinoma in the lower leg: a case report and review of the literature". Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 209 (1): 53–9. doi:10.1620/tjem.209.53. PMID 16636523.

- ↑ Springfield DS, Rosenberg AE, Mankin HJ, Mindell ER (1994). "Relationship between osteofibrous dysplasia and adamantinoma". Clin Orthop Relat Res (309): 234–44. PMID 7994967.

- ↑ Gleason, Briana C.; Liegl-Atzwanger, Bernadette (2008). "Osteofibrous Dysplasia and Adamantinoma in Children and Adolescents: A Clinicopathologic Reappraisal". American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 32 (3): 363–376. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e318150d53e. PMID 18300815. S2CID 22076947.

- 1 2 3 Ernest U. Conrad (2008). Orthopaedic Oncology: Diagnosis and Treatment. Thieme. pp. 143–145. ISBN 9781588905239. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- ↑ J.W. Cusack (1827). "Report of the amputations of the lower jaw". Dublin Hosp Rec. 4: 1–38.

- ↑ L. Malassez (1885). "Sur Le role des debris epitheliaux papdentaires". Arch Physiol Norm Pathol. 5: 309–340 6:379–449.

- ↑ R.H. Ivey; H.R. Churchill (1930). "The need of a standardized surgical and pathological classification of tumors and anomalies of dental origin". Am Assoc Dent Sch Trans. 7: 240–245.

- ↑ Madhup, R; Kirti, S; Bhatt, M; Srivastava, M; Sudhir, S; Srivastava, A (Jan 2006). "Giant ameloblastoma of jaw successfully treated by radiotherapy". Oral Oncology Extra. 42 (1): 22–25. doi:10.1016/j.ooe.2005.08.004.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |