Retinal

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

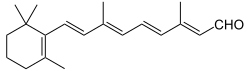

| Preferred IUPAC name

(2E,4E,6E,8E)-3,7-Dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenal | |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.760 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C20H28O |

| Molar mass | 284.443 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Orange crystals from petroleum ether[1] |

| Melting point | 61 to 64 °C (142 to 147 °F; 334 to 337 K)[1] |

Solubility in water |

Nearly insoluble |

| Solubility in fat | Soluble |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

retinol; retinoic acid; beta-carotene; dehydroretinal; 3-hydroxyretinal; 4-hydroxyretinal |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Retinal (also known as retinaldehyde) is a polyene chromophore. Retinal, bound to proteins called opsins, is the chemical basis of visual phototransduction, the light-detection stage of visual perception (vision).

Some microorganisms use retinal to convert light into metabolic energy.

There are many forms of vitamin A — all of which are converted to retinal, which cannot be made without them. Retinal itself is considered a form of vitamin A when eaten by an animal. The number of different molecules that can be converted to retinal varies from species to species. Retinal was originally called retinene,[2] and renamed[3] after it was discovered to be vitamin A aldehyde.[4][5]

Vertebrate animals ingest retinal directly from meat, or they produce retinal from carotenoids — either from α-carotene or β-carotene — both of which are carotenes. They also produce it from β-cryptoxanthin, a type of xanthophyll. These carotenoids must be obtained from plants or other photosynthetic organisms. No other carotenoids can be converted by animals to retinal. Some carnivores cannot convert any carotenoids at all. The other main forms of vitamin A — retinol and a partially active form, retinoic acid — may both be produced from retinal.

Invertebrates such as insects and squid use hydroxylated forms of retinal in their visual systems, which derive from conversion from other xanthophylls.

Vitamin A metabolism

Living organisms produce retinal (RAL) by irreversible oxidative cleavage of carotenoids.[6]

For example:

- beta-carotene + O2 → 2 retinal,

catalyzed by a beta-carotene 15,15'-monooxygenase[7] or a beta-carotene 15,15'-dioxygenase.[8]

Just as carotenoids are the precursors of retinal, retinal is the precursor of the other forms of vitamin A. Retinal is interconvertible with retinol (ROL), the transport and storage form of vitamin A:

- retinal + NADPH + H+ ⇌ retinol + NADP+

- retinol + NAD+ ⇌ retinal + NADH + H+,

catalyzed by retinol dehydrogenases (RDHs)[9] and alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs).[10]

Retinol is called vitamin A alcohol or, more often, simply vitamin A. Retinal can also be oxidized to retinoic acid (RA):

- retinal + NAD+ + H2O → retinoic acid + NADH + H+ (catalyzed by RALDH)

- retinal + O2 + H2O → retinoic acid + H2O2 (catalyzed by retinal oxidase),

catalyzed by retinal dehydrogenases[11] also known as retinaldehyde dehydrogenases (RALDHs)[10] as well as retinal oxidases.[12]

Retinoic acid, sometimes called vitamin A acid, is an important signaling molecule and hormone in vertebrate animals.

Vision

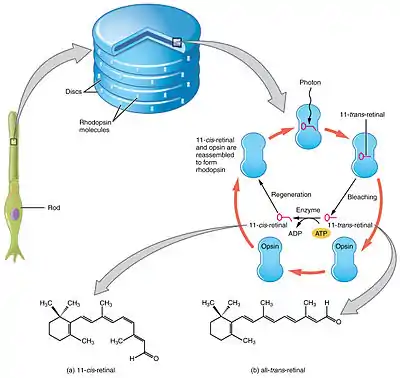

Retinal is a conjugated chromophore. In the human eye, retinal begins in an 11-cis-retinal configuration, which — upon capturing a photon of the correct wavelength — straightens out into an all-trans-retinal configuration. This configuration change pushes against an opsin protein in the retina, which triggers a chemical signaling cascade, which can result in perception of light or images by the human brain. The absorbance spectrum of the chromophore depends on its interactions with the opsin protein to which it is bound, so that different retinal-opsin complexes will absorb photons of different wavelengths (i.e., different colors of light).

Opsins

Opsins are proteins and the retinal-binding visual pigments found in the photoreceptor cells in the retinas of eyes. An opsin is arranged into a bundle of seven transmembrane alpha-helices connected by six loops. In rod cells, the opsin molecules are embedded in the membranes of the disks, which are entirely inside of the cell. The N-terminus head of the molecule extends into the interior of the disk, and the C-terminus tail extends into the cytoplasm of the cell. In cone cells, the disks are defined by the cell's plasma membrane, so that the N-terminus head extends outside of the cell. Retinal binds covalently to a lysine on the transmembrane helix nearest the C-terminus of the protein through a Schiff base linkage. Formation of the Schiff base linkage involves removing the oxygen atom from retinal and two hydrogen atoms from the free amino group of lysine, giving H2O. Retinylidene is the divalent group formed by removing the oxygen atom from retinal, and so opsins have been called retinylidene proteins.

Opsins are prototypical G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs).[13] Bovine rhodopsin, the opsin of the rod cells of cattle, was the first GPCR to have its X-ray structure determined.[14] Bovine rhodopsin contains 348 amino acid residues. The retinal chromophore binds at Lys296.

Although mammals use retinal exclusively as the opsin chromophore, other groups of animals additionally use four chromophores closely related to retinal: 3,4-didehydroretinal (vitamin A2), (3R)-3-hydroxyretinal, (3S)-3-hydroxyretinal (both vitamin A3), and (4R)-4-hydroxyretinal (vitamin A4). Many fish and amphibians use 3,4-didehydroretinal, also called dehydroretinal. With the exception of the dipteran suborder Cyclorrhapha (the so-called higher flies), all insects examined use the (R)-enantiomer of 3-hydroxyretinal. The (R)-enantiomer is to be expected if 3-hydroxyretinal is produced directly from xanthophyll carotenoids. Cyclorrhaphans, including Drosophila, use (3S)-3-hydroxyretinal.[15][16] Firefly squid have been found to use (4R)-4-hydroxyretinal.

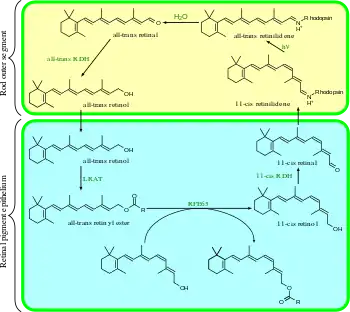

Visual cycle

The visual cycle is a circular enzymatic pathway, which is the front-end of phototransduction. It regenerates 11-cis-retinal. For example, the visual cycle of mammalian rod cells is as follows:

- all-trans-retinyl ester + H2O → 11-cis-retinol + fatty acid; RPE65 isomerohydrolases;[17]

- 11-cis-retinol + NAD+ → 11-cis-retinal + NADH + H+; 11-cis-retinol dehydrogenases;

- 11-cis-retinal + aporhodopsin → rhodopsin + H2O; forms Schiff base linkage to lysine, -CH=N+H-;

- rhodopsin + hν → metarhodopsin II (i.e., 11-cis photoisomerizes to all-trans):

- (rhodopsin + hν → photorhodopsin → bathorhodopsin → lumirhodopsin → metarhodopsin I → metarhodopsin II);

- metarhodopsin II + H2O → aporhodopsin + all-trans-retinal;

- all-trans-retinal + NADPH + H+ → all-trans-retinol + NADP+; all-trans-retinol dehydrogenases;

- all-trans-retinol + fatty acid → all-trans-retinyl ester + H2O; lecithin retinol acyltransferases (LRATs).[18]

Steps 3, 4, 5, and 6 occur in rod cell outer segments; Steps 1, 2, and 7 occur in retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells.

RPE65 isomerohydrolases are homologous with beta-carotene monooxygenases;[6] the homologous ninaB enzyme in Drosophila has both retinal-forming carotenoid-oxygenase activity and all-trans to 11-cis isomerase activity.[19]

Microbial rhodopsins

All-trans-retinal is also an essential component of microbial, opsins such as bacteriorhodopsin, channelrhodopsin, and halorhodopsin. In these molecules, light causes the all-trans-retinal to become 13-cis retinal, which then cycles back to all-trans-retinal in the dark state. These proteins are not evolutionarily related to animal opsins and are not GPCRs; the fact that they both use retinal is a result of convergent evolution.[20]

History

The American biochemist George Wald and others had outlined the visual cycle by 1958. For his work, Wald won a share of the 1967 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Haldan Keffer Hartline and Ragnar Granit.[21]

See also

- Purple Earth hypothesis

- Sensory nervous system

- Visual perception

- Visual phototransduction

References

- 1 2 Merck Index, 13th Edition, 8249

- ↑ WALD, GEORGE (14 July 1934). "Carotenoids and the Vitamin A Cycle in Vision". Nature. 134 (3376): 65. Bibcode:1934Natur.134...65W. doi:10.1038/134065a0. S2CID 4022911.

- ↑ Wald, G (11 October 1968). "Molecular basis of visual excitation". Science. 162 (3850): 230–9. Bibcode:1968Sci...162..230W. doi:10.1126/science.162.3850.230. PMID 4877437.

- ↑ MORTON, R. A.; GOODWIN, T. W. (1 April 1944). "Preparation of Retinene in Vitro". Nature. 153 (3883): 405–406. Bibcode:1944Natur.153..405M. doi:10.1038/153405a0. S2CID 4111460.

- ↑ BALL, S; GOODWIN, TW; MORTON, RA (1946). "Retinene1-vitamin A aldehyde". The Biochemical Journal. 40 (5–6): lix. PMID 20341217.

- 1 2 von Lintig, Johannes; Vogt, Klaus (2000). "Filling the Gap in Vitamin A Research: Molecular Identification of An Enzyme Cleaving Beta-carotene to Retinal". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (16): 11915–11920. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.16.11915. PMID 10766819.

- ↑ Woggon, Wolf-D. (2002). "Oxidative cleavage of carotenoids catalyzed by enzyme models and beta-carotene 15,15'-monooxygenase". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 74 (8): 1397–1408. doi:10.1351/pac200274081397.

- ↑ Kim, Yeong-Su; Kim, Nam-Hee; Yeom, Soo-Jin; Kim, Seon-Won; Oh, Deok-Kun (2009). "In Vitro Characterization of a Recombinant Blh Protein from an Uncultured Marine Bacterium as a β-Carotene 15,15′-Dioxygenase". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (23): 15781–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.002618. PMC 2708875. PMID 19366683.

- ↑ Lidén, M; Eriksson, U (2006). "Understanding Retinol Metabolism: Structure and Function of Retinol Dehydrogenases". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (19): 13001–04. doi:10.1074/jbc.R500027200. PMID 16428379.

- 1 2 Duester, G (September 2008). "Retinoic Acid Synthesis and Signaling during Early Organogenesis". Cell. 134 (6): 921–31. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. PMC 2632951. PMID 18805086.

- ↑ Lin, Min; Zhang, Min; Abraham, Michael; Smith, Susan M.; Napoli, Joseph L. (2003). "Mouse Retinal Dehydrogenase 4 (RALDH4), Molecular Cloning, Cellular Expression, and Activity in 9-cis-Retinoic Acid Biosynthesis in Intact Cells". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (11): 9856–9861. doi:10.1074/jbc.M211417200. PMID 12519776.

- ↑ "KEGG ENZYME: 1.2.3.11 retinal oxidase". Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ↑ Lamb, T D (1996). "Gain and kinetics of activation in the G-protein cascade of phototransduction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 93 (2): 566–570. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93..566L. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.2.566. PMC 40092. PMID 8570596.

- ↑ Palczewski, Krzysztof; Kumasaka, Takashi; Hori, T; Behnke, CA; Motoshima, H; Fox, BA; Le Trong, I; Teller, DC; et al. (2000). "Crystal Structure of Rhodopsin: A G Protein-Coupled Receptor". Science. 289 (5480): 739–745. Bibcode:2000Sci...289..739P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1012.2275. doi:10.1126/science.289.5480.739. PMID 10926528.

- ↑ Seki, Takaharu; Isono, Kunio; Ito, Masayoshi; Katsuta, Yuko (1994). "Flies in the Group Cyclorrhapha Use (3S)-3-Hydroxyretinal as a Unique Visual Pigment Chromophore". European Journal of Biochemistry. 226 (2): 691–696. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20097.x. PMID 8001586.

- ↑ Seki, Takaharu; Isono, Kunio; Ozaki, Kaoru; Tsukahara, Yasuo; Shibata-Katsuta, Yuko; Ito, Masayoshi; Irie, Toshiaki; Katagiri, Masanao (1998). "The metabolic pathway of visual pigment chromophore formation in Drosophila melanogaster: All-trans (3S)-3-hydroxyretinal is formed from all-trans retinal via (3R)-3-hydroxyretinal in the dark". European Journal of Biochemistry. 257 (2): 522–527. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2570522.x. PMID 9826202.

- ↑ Moiseyev, Gennadiy; Chen, Ying; Takahashi, Yusuke; Wu, Bill X.; Ma, Jian-xing (2005). "RPE65 is the isomerohydrolase in the retinoid visual cycle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (35): 12413–12418. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10212413M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503460102. PMC 1194921. PMID 16116091.

- ↑ Jin, Minghao; Yuan, Quan; Li, Songhua; Travis, Gabriel H. (2007). "Role of LRAT on the Retinoid Isomerase Activity and Membrane Association of Rpe65". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (29): 20915–20924. doi:10.1074/jbc.M701432200. PMC 2747659. PMID 17504753.

- ↑ Oberhauser, Vitus; Voolstra, Olaf; Bangert, Annette; von Lintig, Johannes; Vogt, Klaus (2008). "NinaB combines carotenoid oxygenase and retinoid isomerase activity in a single polypeptide". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (48): 19000–5. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10519000O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807805105. PMC 2596218. PMID 19020100.

- ↑ Chen, De-Liang; Wang, Guang-yu; Xu, Bing; Hu, Kun-Sheng (2002). "All-trans to 13-cis retinal isomerization in light-adapted bacteriorhodopsin at acidic pH". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 66 (3): 188–194. doi:10.1016/S1011-1344(02)00245-2. PMID 11960728.

- ↑ Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1967

Further reading

- Fernald, Russell D. (2006). "Casting a Genetic Light on the Evolution of Eyes". Science. 313 (5795): 1914–1918. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1914F. doi:10.1126/science.1127889. PMID 17008522. S2CID 84439732.

- Amora, Tabitha L.; Ramos, Lavoisier S.; Galan, Jhenny F.; Birge, Robert R. (2008). "Spectral Tuning of Deep Red Cone Pigments". Biochemistry. 47 (16): 4614–20. doi:10.1021/bi702069d. PMC 2492582. PMID 18370404.

- Barlow, H.B.; Levick, W.R.; Yoon, M. (1971). "Responses to single quanta of light in retinal ganglion cells of the cat". Vision Research. 11 (Supplement 3): 87–101. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(71)90033-2. PMID 5293890.

- Baylor, D A; Lamb, T D; Yau, K W (1979). "Responses of retinal rods to single photons". Journal of Physiology. 288: 613–634. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012716 (inactive 31 October 2021). PMC 1281447. PMID 112243.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021 (link) - Fan, Jie; Woodruff, Michael L; Cilluffo, Marianne C; Crouch, Rosalie K; Fain, Gordon L (2005). "Opsin activation of transduction in the rods of dark-reared Rpe65 knockout mice". Journal of Physiology. 568 (1): 83–95. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2005.091942. PMC 1474752. PMID 15994181.

- Hecht, Selig; Shlaer, Simon; Pirenne, Maurice Henri (1942). "Energy, Quanta, and Vision". Journal of General Physiology. 25 (6): 819–840. doi:10.1085/jgp.25.6.819. PMC 2142545. PMID 19873316.

- Kawaguchi, Riki; Yu, Jiamei; Honda, Jane; Hu, Jane; Whitelegge, Julian; Ping, Peipei; Wiita, Patrick; Bok, Dean; Sun, Hui (2007). "A Membrane Receptor for Retinol Binding Protein Mediates Cellular Uptake of Vitamin A". Science. 315 (5813): 820–825. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..820K. doi:10.1126/science.1136244. PMID 17255476. S2CID 25258551.

- Kloer, Daniel P.; Ruch, Sandra; Al-Babili, Salim; Beyer, Peter; Schulz, Georg E. (2005). "The Structure of a Retinal-Forming Carotenoid Oxygenase". Science. 308 (5719): 267–269. Bibcode:2005Sci...308..267K. doi:10.1126/science.1108965. PMID 15821095. S2CID 6318853.

- Luo, Dong-Gen; Xue, Tian; Yau, King-Wai (2008). "How vision begins: An odyssey". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (29): 9855–9862. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9855L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708405105. PMC 2481352. PMID 18632568. Good historical review.

- Prado-Cabrero, Alfonso; Scherzinger, Daniel; Avalos, Javier; Al-Babili, Salim (2007). "Retinal Biosynthesis in Fungi: Characterization of the Carotenoid Oxygenase CarX from Fusarium fujikuroi". Eukaryotic Cell. 6 (4): 650–657. doi:10.1128/EC.00392-06. PMC 1865656. PMID 17293483.

- Racker, Efraim; Stoeckenius, Walther (1974). "Reconstitution of Purple Membrane Vesicles Catalyzing Light-driven Proton Uptake and Adenosine Triphosphate Formation". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 249 (2): 662–663. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)43080-9. PMID 4272126.

- Sadekar, Sumedha; Raymond, Jason; Blankenship, Robert E. (2006). "Conservation of Distantly Related Membrane Proteins: Photosynthetic Reaction Centers Share a Common Structural Core". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (11): 2001–2007. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl079. PMID 16887904.

- Salom, David; Lodowski, David T.; Stenkamp, Ronald E.; Le Trong, Isolde; Golczak, Marcin; Jastrzebska, Beata; Harris, Tim; Ballesteros, Juan A.; Palczewski, Krzysztof (2006). "Crystal structure of a photoactivated deprotonated intermediate of rhodopsin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (44): 16123–16128. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10316123S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608022103. PMC 1637547. PMID 17060607.

- Schäfer, Günter; Engelhard, Martin; Müller, Volker (1999). "Bioenergetics of the Archaea". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 63 (3): 570–620. doi:10.1128/MMBR.63.3.570-620.1999. PMC 103747. PMID 10477309.

- Schmidt, Holger; Kurtzer, Robert; Eisenreich, Wolfgang; Schwab, Wilfried (2006). "The Carotenase AtCCD1 from Arabidopsis thaliana Is a Dioxygenase". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (15): 9845–9851. doi:10.1074/jbc.M511668200. PMID 16459333.

- Send, Robert; Sundholm, Dage (2007). "Stairway to the conical intersection: A computational study of retinal isomerization". Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 111 (36): 8766–8773. Bibcode:2007JPCA..111.8766S. doi:10.1021/jp073908l. PMID 17713894.

- Su, Chih-Ying; Luo, Dong-Gen; Terakita, Akihisa; Shichida, Yoshinori; Liao, Hsi-Wen; Kazmi, Manija A.; Sakmar, Thomas P.; Yau, King-Wai (2006). "Parietal-Eye Phototransduction Components and Their Potential Evolutionary Implications". Science. 311 (5767): 1617–1621. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1617S. doi:10.1126/science.1123802. PMID 16543463. S2CID 28604455.

- Venter, J. Craig; Remington, K; Heidelberg, JF; Halpern, AL; Rusch, D; Eisen, JA; Wu, D; Paulsen, I; et al. (2004). "Environmental Genome Shotgun Sequencing of the Sargasso Sea". Science. 304 (5667): 66–74. Bibcode:2004Sci...304...66V. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.124.1840. doi:10.1126/science.1093857. PMID 15001713. S2CID 1454587. The oceans are full of type 1 rhodopsin.

- Wang, Tao; Jiao, Yuchen; Montell, Craig (2007). "Dissection of the pathway required for generation of vitamin A and for Drosophila phototransduction". Journal of Cell Biology. 177 (2): 305–316. doi:10.1083/jcb.200610081. PMC 2064138. PMID 17452532.

- Waschuk, Stephen A.; Bezerra, Arandi G.; Shi, Lichi; Brown, Leonid S. (2005). "Leptosphaeria rhodopsin: Bacteriorhodopsin-like proton pump from a eukaryote". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (19): 6879–6883. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.6879W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409659102. PMC 1100770. PMID 15860584.

- Yokoyama, Shozo; Radlwimmer, F. Bernhard (2001). "The molecular genetics and evolution of red and green color vision in vertebrates". Genetics. 158 (4): 1697–1710. doi:10.1093/genetics/158.4.1697. PMC 1461741. PMID 11545071.

- Briggs, Winslow R.; Spudich, John L., eds. (2005). Handbook of Photosensory Receptors. Wiley. ISBN 978-3-527-31019-7.

- Wald, George (1967). "Nobel Lecture: The Molecular Basis of Visual Excitation" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-02-23.

External links

- First Steps of Vision - National Health Museum

- Vision and Light-Induced Molecular Changes

- Retinal Anatomy and Visual Capacities

- Retinal, Imperial College v-chemlib