Congenital cytomegalovirus infection

| Congenital cytomegalovirus infection | |

|---|---|

| Other names: CMV infection[1] | |

| |

| Micrograph of a cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection of the placenta (CMV placentitis). The characteristic large nucleus of a CMV infected cell is seen off-centre at the bottom-right of the image. H&E stain | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | No symptoms, small baby, rash, yellow eyes, large liver, retina inflammation, seizures[2] |

| Complications | Loss of hearing or vision, developmental disability, small head[1] |

| Usual onset | Newborn baby[1] |

| Causes | Cytomegalovirus[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Tests on urine, saliva, blood before age 3-weeks[2] |

| Prevention | Hand washing, avoid touching saliva or urine of children[1] |

| Frequency | Common[1] |

| Deaths | 1% risk[3] |

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in a newborn baby.[1] Most, about 90%, have no symptoms.[1][4] Some babies are born small.[1] Other symptoms may include a rash, yellow eyes, large liver, retina inflammation, or seizures.[1][2] Complications occur in about 20% and may include loss of hearing or vision, developmental disability, or a small head.[1]

It is caused when a mother contracts CMV during pregnancy and passes it to her unborn baby.[1] Both reactivation or reinfection can result in the disease, with first time infections having a greater risk of around 32%.[5] The risk is greatest if the mother is infected in later pregnancy, although the risk of severe disease is greatest if infected in early pregnancy.[2] Most infected pregnant women have no symptoms, while some present with glandular fever-like symptoms.[1][4] Diagnosis is by tests; on preferably urine, although saliva and blood can be used, in the first 3-weeks after birth.[2] Blood tests may reveal a raised ALT or low platelets.[5]

The chance of infection is reduced by hand washing, and avoiding touching saliva or urine of young children.[1] There may be some benefit from taking valganciclovir for six months in affected babies, though side effects may occur.[1][2] Ganciclovir is another option.[6] Routine hearing and vision testing is recommended among those affected.[6]

Worldwide the condition is common, and likely underreported.[3] In the Canada, the United States, and Western Europe it is estimated to effect around 1 in 200 babies.[1][4] Rates are three times higher in low and middle income countries.[3] Death occurs in about 1% of those affected.[3] The condition was first clearly described in the 1960s;[7] though suspected cases have occurred since the 1930s.[8] The economic burden appears greater in low and middle income countries.[3]

Signs and symptoms

For infants who are infected by their mothers before birth, two potential adverse scenarios exist:

- Generalized infection may occur in the infant, and can cause complications such as low birth weight, microcephaly, seizures, petechial rash similar to the "blueberry muffin" rash of congenital rubella syndrome, and moderate hepatosplenomegaly (with jaundice). Though severe cases can be fatal, with supportive treatment most infants with CMV disease will survive. However, from 80% to 90% will have complications within the first few years of life that may include hearing loss, vision impairment, and varying degrees of learning disability.

- Another 5% to 10% of infants who are infected but without symptoms at birth will subsequently have varying degrees of hearing and mental or coordination problems. CMV is the most common cause of non-genetic sensorineural hearing loss in children. The onset of hearing loss can occur at any point during childhood, although commonly within the first decade. It is progressive and can affect both ears. The earlier the mother contracts the virus during pregnancy the more severe the effects are on the fetus, similarly the incidence of SNHL is dependent on which trimester of pregnancy CMV is contracted. The virus accounts for 20% of sensorineural hearing loss in children.[9][10]

These risks appear to be almost exclusively associated with women who previously have not been infected with CMV and who are having their first infection with the virus during pregnancy. There appears to be little risk of CMV-related complications for women who have been infected at least 6 months prior to conception. For this group, which makes up 50% to 80% of the women of child-bearing age, the rate of newborn CMV infection is 1%, and these infants appear to have no significant illness or abnormalities.[11]

The virus can also be transmitted to the infant at delivery from contact with genital secretions or later in infancy through breast milk. However, these infections usually result in little or no clinical illness in the infant. CMV can also be transferred through blood transfusions and close contact with large groups of children.[12]

To summarise, during a pregnancy when a woman who has never had CMV infection becomes infected with CMV, there is a risk that after birth the infant may have CMV-related complications, the most common of which are associated with hearing loss, visual impairment, or diminished mental and motor capabilities. On the other hand, healthy infants and children who acquire CMV after birth have few, if any, symptoms or complications. However, infants born preterm and infected with CMV after birth (especially via breastmilk[13]) may experience cognitive and motor impairments later in life.[14][15]

Symptoms associated with CMV, such as hearing loss, can result in further developmental delay. A delay in general speech and language development is more common in children with CMV.[16] Children with symptomatic CMV have been found to have a greater incidence of long-term neurological and neurodevelopmental complications than children with fetal alcohol syndrome or down syndrome.[12]

Congenital cytomegalovirus infection can be an important cause of intraventricular hemorrhage and neonatal encephalopathy.[17]

Diagnosis

CMV testing

People infected with CMV develop antibodies to it, initially IgM later IgG indicating current infection and immunity respectively. The virus can be diagnosed through viral isolation, or using blood, urine, or saliva samples.[10]

When infected with CMV, most women have no symptoms, but some may have symptoms resembling mononucleosis. Women who develop a mononucleosis-like illness during pregnancy should consult their medical provider.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend routine maternal screening for CMV infection during pregnancy because there is no test that can definitively rule out primary CMV infection during pregnancy. Women who are concerned about CMV infection during pregnancy should practice CMV prevention measures. Considering that the CMV virus is present in saliva, urine, tears, blood, mucus, and other bodily fluids, frequent hand washing with soap and water is important after contact with diapers or oral secretions, especially with a child who is in daycare or interacting with other young children on a regular basis.

A diagnosis of congenital CMV infection can be made if the virus is found in an infant's urine, saliva, blood, or other body tissues during the first week after birth. Antibody tests cannot be used to diagnose congenital CMV; a diagnosis can only be made if the virus is detected during the first week of life. Congenital CMV cannot be diagnosed if the infant is tested more than one week after birth.

Visually healthy infants are not routinely tested for CMV infection although only 10–20% will show signs of infection at birth though up to 80% may go onto show signs of prenatal infection in later life. If a pregnant woman finds out that she has become infected with CMV for the first time during her pregnancy, she should have her infant tested for CMV as soon as possible after birth.

Prenatal testing

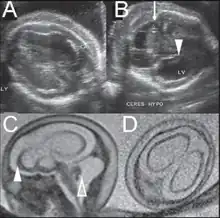

Fetal brain ultrasound scan at 24 weeks gestation: thalamic calcifications, hyperechogenic foci in right ventricular wall, asymmetric ventriculomegaly

Fetal brain ultrasound scan at 24 weeks gestation: thalamic calcifications, hyperechogenic foci in right ventricular wall, asymmetric ventriculomegaly Fetal brain ultrasound scan at 36 weeks gestation: microcephaly

Fetal brain ultrasound scan at 36 weeks gestation: microcephaly

Treatment

Treatment for CMV infection should start at 1 month of age and should occur for 6 months. The options for treatment are intravenous ganciclovir and oral valganciclovir. After diagnosis, it is important to further investigate any possible evidence of end-organ disease and symptoms through blood tests, imaging, ophthalmology tests, and hearing tests.[9]

Prevention

Recommendations for pregnant women with regard to CMV infection:

- Throughout the pregnancy, practice good personal hygiene, especially handwashing with soap and water, after contact with diapers or oral secretions (particularly with a child who is in day care). Sharing of food, eating and drinking utensils, and contact with toddlers' saliva should be avoided.

- Women who develop a mononucleosis-like illness during pregnancy should be evaluated for CMV infection and counseled about the possible risks to the unborn child.

- Laboratory testing for antibody to CMV can be performed to determine if a woman has already had CMV infection.

- Recovery of CMV from the cervix or urine of women at or before the time of delivery does not warrant a cesarean section.

- The demonstrated benefits of breast-feeding outweigh the minimal risk of acquiring CMV from the breast-feeding mother.

- There is no need to either screen for CMV or exclude CMV-excreting children from schools or institutions because the virus is frequently found in many healthy children and adults.

Treatment with hyperimmune globulin in mothers with primary CMV infection has been shown to be effective in preventing congenital disease in several studies.[18][19][20][21] One study did not show significant decrease in the risk of congenital cytomegalovirus infection.[22]

Childcare

Most healthy people working with infants and children face no special risk from CMV infection. However, for women of child-bearing age who previously have not been infected with CMV, there is a potential risk to the developing unborn child (the risk is described above in the Pregnancy section). Contact with children who are in day care, where CMV infection is commonly transmitted among young children (particularly toddlers), may be a source of exposure to CMV. Since CMV is transmitted through contact with infected body fluids, including urine and saliva, child care providers (meaning day care workers, special education teachers, as well as mothers) should be educated about the risks of CMV infection and the precautions they can take.[23] Day care workers appear to be at a greater risk than hospital and other health care providers, and this may be due in part to the increased emphasis on personal hygiene in the health care setting.

Recommendations for individuals providing care for infants and children:

- Employees should be educated concerning CMV, its transmission, and hygienic practices, such as handwashing, which minimize the risk of infection.

- Susceptible nonpregnant women working with infants and children should not routinely be transferred to other work situations.

- Pregnant women working with infants and children should be informed of the risk of acquiring CMV infection and the possible effects on the unborn child.

- Routine laboratory testing for CMV antibody in female workers is not specifically recommended due to its high occurrence, but can be performed to determine their immune status.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, approximately 1 in 100 to 500 babies are born with congenital CMV. Approximately 1 in 3000 will show symptoms and 1 in 7000 will die.[24] Congenital HCMV infection occurs when the mother has a primary infection (or reactivation) during pregnancy. Due to the lower seroprevalence of HCMV in industrialized countries and higher socioeconomic groups, congenital infections are actually less common in poorer communities, where more women of child-bearing age are already seropositive. In industrialized countries up to 8% of HCMV seronegative mothers contract primary HCMV infection during pregnancy, of which roughly 50% will transmit to the fetus.[25] Between 10 and 15% of infected fetuses are then born with symptoms,[9] which may include pneumonia, gastrointestinal, retinal and neurological disease.[26][27] 10-15% of asymptomatic babies will develop long term neurological effects. SNHL is found in 35% of children with CMV, cognitive deficits have been found in 66% of children with CMV, and death occurs in 4% of children.[10] HCMV infection occurs in roughly 1% of all neonates with those who are not congenitally infected contracting the infection possibly through breast milk.[28][29][30] Other sources of neonatal infection are bodily fluids which are known to contain high titres in shedding individuals: saliva (<107copies/ml) and urine (<105copies/ml )[31][32] seem common routes of transmission.

The incidence of primary CMV infection in pregnant women in the United States varies from 1% to 3%. Healthy pregnant women are not at special risk for disease from CMV infection. When infected with CMV, most women have no symptoms and very few have a disease resembling infectious mononucleosis. It is their developing fetuses that may be at risk for congenital CMV disease. CMV remains the most important cause of congenital viral infection in the United States. HCMV is the most common cause of congenital infection in humans and intrauterine primary infections are more common than other well-known infections and syndromes, including Down Syndrome, Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, Spina Bifida, and Pediatric HIV/AIDS.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Prevent the spread of CMV". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 27 May 2022. Archived from the original on 7 August 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Domachowske, Joseph; Suryadevara, Manika (2020). "26. Congenital and perinatal infections". Clinical Infectious Diseases Study Guide: A Problem-Based Approach. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-3-030-50872-2. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ssentongo, P; Hehnly, C; Birungi, P; Roach, MA; Spady, J; Fronterre, C; Wang, M; Murray-Kolb, LE; Al-Shaar, L; Chinchilli, VM; Broach, JR; Ericson, JE; Schiff, SJ (2 August 2021). "Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection Burden and Epidemiologic Risk Factors in Countries With Universal Screening: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA network open. 4 (8): e2120736. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.20736. PMID 34424308. Archived from the original on 26 August 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- 1 2 3 van Zuylen, WJ; Hamilton, ST; Naing, Z; Hall, B; Shand, A; Rawlinson, WD (December 2014). "Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Clinical presentation, epidemiology, diagnosis and prevention". Obstetric medicine. 7 (4): 140–6. doi:10.1177/1753495X14552719. PMID 27512442.

- 1 2 Jones, hristine E.; Heath, Paul T.; Le Doare, Kirsty (2021). "24. GBS and CMV vaccines in pipeline development". In Vesikari, Timo; Damme, Pierre Van (eds.). Pediatric Vaccines and Vaccinations: A European Textbook (Second ed.). Switzerland: Springer. pp. 283–288. ISBN 978-3-030-77172-0.

- 1 2 "Congenital CMV Infection | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 29 September 2022. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ↑ Thigpen, J (1 August 2020). "Congenital Cytomegalovirus-History, Current Practice, and Future Opportunities". Neonatal network : NN. 39 (5): 293–298. doi:10.1891/0730-0832.39.5.293. PMID 32879045.

- ↑ Ho, Monto (June 2008). "The history of cytomegalovirus and its diseases". Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 197 (2): 65–73. doi:10.1007/s00430-007-0066-x.

- 1 2 3 Lim, Yinru; Lyall, Hermione (2017). "Congenital cytomegalovirus – who, when, what-with and why to treat?". Journal of Infection. 74 (1): S89–S94. doi:10.1016/s0163-4453(17)30197-4. ISSN 0163-4453. PMID 28646968.

- 1 2 3 Dobbie, Allison M. (2017). "Evaluation and management of cytomegalovirus-associated congenital hearing loss". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 25 (5): 390–395. doi:10.1097/moo.0000000000000401. ISSN 1068-9508. PMID 28857892.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 556, 566–9. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- 1 2 Coleman, J. L; Steele, R. W (2017). "Preventing Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection". Clinical Pediatrics. 56 (12): 1085–1084. doi:10.1177/0009922817724400. PMID 28825308. S2CID 39691206.

- ↑ Maschmann, J.; Hamprecht, K.; Dietz, K.; Jahn, G.; Speer, C. P. (2001). "Cytomegalovirus Infection of Extremely Low—Birth Weight Infants via Breast Milk". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 33 (12): 1998–2003. doi:10.1086/324345. PMID 11712092.

- ↑ Brecht, K; Goelz, R; Bevot, A; Krägeloh- Mann, I; Wilke, M; Lidzba, K (2015). "Postnatal Human Cytomegalovirus Infection in Preterm Infants Has Long-Term Neuropsychological Sequelae". The Journal of Pediatrics. 166 (4): 834–9.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.11.002. PMID 25466679.

- ↑ Bevot, Andrea; Hamprecht, Klaus; Krägeloh-Mann, Ingeborg; Brosch, Sibylle; Goelz, Rangmar; Vollmer, Brigitte (1 April 2012). "Long-term outcome in preterm children with human cytomegalovirus infection transmitted via breast milk". Acta Paediatrica. 101 (4): e167–e172. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02538.x. PMID 22111513. S2CID 29018739.

- ↑ Korndewal, Marjolein J Oudesluys-Murphy, Anne Marie Kroes, Aloys C M Vossen, Ann C T M de Melker, Hester E (December 2017). "Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Child Development, Quality of Life and Impact on Daily Life". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 36 (12): 1141–1147. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000001663. OCLC 1018138960. PMID 28650934. S2CID 20122101.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Suksumek, N; Scott, JN; Chadha, R; Yusuf, K (July 2013). "Intraventricular hemorrhage and multiple intracranial cysts associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 51 (7): 2466–8. doi:10.1128/JCM.00842-13. PMC 3697656. PMID 23678057.

- ↑ Nigro, G.; Adler, S.P.; La Torre, R.; Best, A.M. (2005). "Passive immunization during pregnancy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (13): 1350–1362. doi:10.1056/nejmoa043337. PMID 16192480. Archived from the original on 2021-12-08. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ↑ Visentin, S.; Manara, R.; Milanese, L.; Da Roit, A.; Salviato, E.; Citton, V.; Magno, F.M.; Morando, C. (2012). "Early primary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy: maternal hyperimmunoglobulin therapy improves outcomes among infants at 1 year of age". Clin Infect Dis. 55 (4): 497–503. doi:10.1093/cid/cis423. PMID 22539662.

- ↑ Nigro, G.; Adler, S.P.; Parruti, G.; Anceschi, M.M.; Coclite, E.; pezone, I.; Di Renzo, G.C. (2012). "Immunoglobulin therapy of fetal cytomegalovirus infection occurring in the first half of pregnancy--a case-control study of the outcome in children". J Infect Dis. 205 (2): 215–227. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir718. PMID 22140265.

- ↑ Buxmann, H.; Stackelberg, O.M.; Schlosser, R.L.; Enders, G.; Gonser, M.; Meyer-Wittkopf, M.; Hamprecht, K.; Enders, M. (2012). "Use of cytomegalovirus hyperimmunoglobulin for prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus disease: a retrospective analysis". J Perinat Med. 40 (4): 439–446. doi:10.1515/jpm-2011-0257. PMID 22752777.

- ↑ Revello, M. G.; Lazzarotto, T.; Guerra, B.; Spinillo, A.; Ferrazzi, E.; Kustermann, A.; Guaschino, S.; Vergani, P.; Todros, T.; Frusca, T.; Arossa, A.; Furione, M.; Rognoni, V.; Rizzo, Nicola; Gabrielli, Liliana; Klersy, Catherine; Gerna, G. (2014). "A Randomized Trial of Hyperimmune Globulin to Prevent Congenital Cytomegalovirus" (PDF). N Engl J Med. 370 (14): 1316–1326. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1310214. hdl:2434/262989. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 24693891. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-07. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ↑ Pickering, Larry; Baker, Carol; Kimberlin, David; Long, Sarah (2012). 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (PDF) (29 ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-58110-703-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ Butler, Declan (5 July 2016). "Zika raises profile of more common birth-defect virus". Nature. 535 (17): 17. Bibcode:2016Natur.535...17B. doi:10.1038/535017a. PMID 27383962.

- ↑ Adler, Stuart P. (December 2005). "Congenital Cytomegalovirus Screening". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 24 (12): 1105–1106. doi:10.1097/00006454-200512000-00016. PMID 16371874.

- ↑ Barry Schoub; Zuckerman, Arie J.; Banatvala, Jangu E.; Griffiths, Paul E. (2004). "Chapter 2C Cytomegalovirus". Principles and Practice of Clinical Virology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–122. ISBN 978-0-470-84338-3.

- ↑ Vancíková Z, Dvorák P (2001). "Cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals--a review". Curr. Drug Targets Immune Endocr. Metabol. Disord. 1 (2): 179–87. doi:10.2174/1568008013341334. PMID 12476798.

- ↑ Kerrey BT, Morrow A, Geraghty S, Huey N, Sapsford A, Schleiss MR (2006). "Breast milk as a source for acquisition of cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in a premature infant with sepsis syndrome: detection by real-time PCR". J. Clin. Virol. 35 (3): 313–6. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.013. PMID 16300992.

- ↑ Schleiss MR; Dror, Yigal (2006). "Role of breast milk in acquisition of cytomegalovirus infection: recent advances". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 18 (1): 48–52. doi:10.1097/01.mop.0000192520.48411.fa. PMID 16470162.

- ↑ Schleiss MR (2006). "Acquisition of human cytomegalovirus infection in infants via breast milk: natural immunization or cause for concern?". Rev. Med. Virol. 16 (2): 73–82. doi:10.1002/rmv.484. PMID 16287195. S2CID 31680652.

- ↑ Kearns AM, Turner AJ, Eltringham GJ, Freeman R (2002). "Rapid detection and quantification of CMV DNA in urine using LightCycler-based real-time PCR". J. Clin. Virol. 24 (1–2): 131–4. doi:10.1016/S1386-6532(01)00240-2. PMID 11744437.

- ↑ Yoshikawa T, Ihira M, Taguchi H, Yoshida S, Asano Y (2005). "Analysis of shedding of 3 beta-herpesviruses in saliva from patients with connective tissue diseases". J. Infect. Dis. 192 (9): 1530–6. doi:10.1086/496890. PMID 16206067.

External links

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Archived 2023-06-30 at the Wayback Machine—NHS Choices

- CMV: Congenital CMV Infection Archived 2010-08-07 at the Wayback Machine—CDC

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |