Congenital iodine deficiency syndrome

| Congenital iodine deficiency syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Congenital hypothyroidism due to iodine deficiency,[1] endemic cretinism,[2] fetal iodine deficiency syndrome[3] | |

| |

| A man with congenital iodine deficiency syndrome | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Intellectual disability, hearing problems, short stature, dry skin, poor coordination, strabismus, constipation[4] |

| Usual onset | Present at birth[5] |

| Duration | Long-term[5] |

| Types | Neurological, myxoedematous[5] |

| Causes | Mother or baby having iodine deficiency[4][6] |

| Prevention | Iodisation of salt[4] |

| Treatment | Levothyroxine[7] |

| Frequency | Rare (developed world)[8] |

Congenital iodine deficiency syndrome, previously known as endemic cretinism, is intellectual disability with either hearing problems or short stature as a result of endemic goiter.[4] Other symptoms may include dry skin, abnormal reflexes, poor coordination, strabismus, constipation, and voice changes.[4] A goiter may also occur.[4]

It occurs due to either the mother or baby having iodine deficiency due to insufficient dietary intake.[4][6] Onset is estimated to be 3 month to 8 months of gestational age.[5] The food cassave may also play a role.[5] It is divided into two types: neurological and myxoedematous.[5] Less severe cases may be labeled subclinical.[4] It is a type of low thyroid at birth (congenital hypothyroidism).[9]

Prevention is by treating iodine deficiency before people becomes pregnant.[4] Efforts include iodisation of all salt and iodized oil supplements.[4][5] Treatment involves the use of levothyroxine and iodine supplementation.[7][10] However; not all symptoms may be reversible with treatment.[7]

Congenital iodine deficiency syndrome is rare in the developed world.[8] In a population that is severely low on iodine, up to 10 to 30% of the population may be affected.[4] It was previously the most common cause of preventable intellectual disability.[4] The original term for untreated congenital hypothyroidism was "cretinism", which came into use in 1754 in Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie.[4][7] At that time it was common in Switzerland and Northern Italy.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Iodine deficiency causes gradual enlargement of the thyroid gland, referred to as a goiter. Poor length growth is apparent as early as the first year of life. Adult stature without treatment ranges from 100 to 160 cm (3 ft 3 in to 5 ft 3 in), depending on severity, sex, and other genetic factors. Other signs include thickened skin, hair loss, enlarged tongue, and a protruding abdomen.[11] In children, bone maturation and puberty are severely delayed. In adults, ovulation is impeded and infertility is common.[12][13]

Mental deterioration is common. Neurological impairment may be mild, with reduced muscle tone and coordination, or so severe that the person cannot stand or walk. Cognitive impairment may also range from mild to so severe that the person is nonverbal and dependent on others for basic care. Thought and reflexes are slower.[14][15]

Cretinism (Styria), copper engraving, 1815

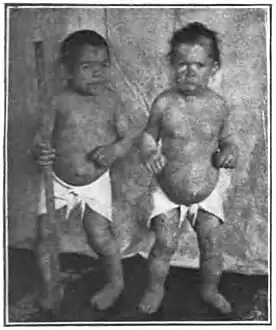

Cretinism (Styria), copper engraving, 1815 People with congenital iodine deficiency syndrome who are 34 and 24 years old

People with congenital iodine deficiency syndrome who are 34 and 24 years old

Cause

Around the world, the most common cause of congenital iodine deficiency syndrome (endemic cretinism)[2] is dietary iodine deficiency.

Iodine is an essential trace element, necessary for the synthesis of thyroid hormones. Iodine deficiency is the most common preventable cause of neonatal and childhood brain damage worldwide.[16] Although iodine is found in many foods, it is not universally present in all soils in adequate amounts. Most iodine, in iodide form, is in the oceans, where the iodide ions are reduced to elemental iodine, which then enters the atmosphere and falls to earth in rain, introducing iodine to soils. Soil deficient in iodine is most common inland, in mountainous areas, and in areas of frequent flooding. It can also occur in coastal regions, where iodine might have been removed from the soil by glaciation, as well as leaching by snow, water and heavy rainfall.[17] Plants and animals grown in iodine-deficient soils are correspondingly deficient. Populations living in those areas without outside food sources are most at risk of iodine deficiency diseases.[18]

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

Dwarfism may also be caused by malnutrition or other hormonal deficiencies, such as insufficient growth hormone secretion, hypopituitarism, decreased secretion of growth hormone-releasing hormone, deficient growth hormone receptor activity and downstream causes, such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) deficiency.[19]

Prevention

Congenital iodine deficiency has been almost eliminated in developed countries through iodine supplementation of food and by newborn screening utilizing a blood test for thyroid function.[20]

There are public health campaigns in many countries which involve iodine administration. As of December 2019, 122 countries have mandatory iodine food fortification programs.[21]

Treatment

Treatment consists of thyroxine (T4). Thyroxine must be dosed as tablets only, even to newborns, as the liquid oral suspensions and compounded forms cannot be depended on for reliable dosing. For infants, the T4 tablets are generally crushed and mixed with breast milk, formula milk or water. If the medication is mixed with formulas containing iron or soya products, larger doses may be required, as these substances may alter the absorption of thyroid hormone from the gut.[22] Monitoring TSH blood levels every 2–3 weeks during the first months of life is recommended to ensure that affected infants are at the high end of normal range.

Epidemiology

In terms of the epidemiology of Endemic cretinism, we find its prevalence in Africa is between 1.2 percent to 6 percent . Beginning in the year 2000, reports of Endemic cretinism declined significantly.[23]

History

A goiter is the most specific clinical marker of either the direct or indirect insufficient intake of iodine in the human body. There is evidence of goiter, and its medical treatment with iodine-rich algae and burnt sponges, in Chinese, Egyptian, and Roman ancient medical texts. In 1848, King Carlo Alberto of Sardinia commissioned the first epidemiological study of congenital iodine deficiency syndrome, in northern Savoy where it was frequent. In past centuries, the well reported social diseases prevalent among the poorer social classes and farmers, caused by dietary and agricultural monocultures, were: pellagra, rickets, beriberi, scurvy in long-term sailors, and the endemic goiter caused by iodine deficiency. However, this disease was less mentioned in medical books because it was erroneously considered to be an aesthetic rather than a clinical disorder.[24]

Congenital iodine-deficiency syndrome was especially common in areas of southern Europe around the Alps and was often described by ancient Roman writers and depicted by artists. The earliest Alpine mountain climbers sometimes came upon whole villages affected by it.[25] The prevalence of the condition was described from a medical perspective by several travellers and physicians in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[26] At that time the cause was not known and it was often attributed to "stagnant air" in mountain valleys or "bad water". The proportion of people affected varied markedly throughout southern Europe and even within very small areas, it might be common in one valley and not another. The number of severely affected persons was always a minority, and most persons were only affected to the extent of having a goitre and some degree of reduced cognition and growth. The majority of such cases were still socially functional in their pastoral villages.

More mildly affected areas of Europe and North America in the 19th century were referred to as "goitre belts". The degree of iodine deficiency was milder and manifested primarily as thyroid enlargement rather than severe mental and physical impairment. In Switzerland, for example, where soil does not contain a large amount of iodine, cases of congenital iodine deficiency syndrome were very abundant and even considered genetically caused. As the variety of food sources dramatically increased in Europe and North America and the populations became less completely dependent on locally grown food, the prevalence of endemic goitre diminished. This is supported by a 1979 WHO publication which concluded that "changes in the origin of food supplies may account for the otherwise unexplained disappearance of endemic goitre from a number of localities during the past 50 years".[27]

The early 20th century saw the discovery of the relationships of neurological impairment with hypothyroidism due to iodine deficiency. Both have been largely eliminated in the developed world.[28]

Terminology

The term cretin was originally used to describe a person affected by this condition, but, as with words such as spastic and lunatic, it underwent pejoration and is now considered derogatory and inappropriate.[29] Cretin became a medical term in the 18th century, from an Occitan and an Alpine French expression, prevalent in a region where persons with such a condition were especially common (see below); it saw wide medical use in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and was a "tick box" category on Victorian-era census forms in the UK. The term spread more widely in popular English as a markedly derogatory term for a person who behaves stupidly. Because of its pejorative connotations in popular speech, current usage among health care professionals has abandoned the noun "cretin" referring to a person. The noun cretinism, referring to the condition, still occurs in medical literature and textbooks but its use is waning.

The etymology of cretin is uncertain. Several hypotheses exist. The most common derivation provided in English dictionaries is from the Alpine French dialect pronunciation of the word Chrétien ("(a) Christian"), which was a greeting there. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the translation of the French term into "human creature" implies that the label "Christian" is a reminder of the humanity of the afflicted, in contrast to brute beasts.[30] Other sources suggest that Christian describes the person's "Christ-like" inability to sin, stemming, in such cases, from an incapacity to distinguish right from wrong.[31][32]

Other speculative etymologies have been offered:

References

- ↑ "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- 1 2 "ICD-10 Version:2019". Archived from the original on 2020-03-31. Retrieved 2022-05-29.

- ↑ "MalaCards integrated aliases for Fetal Iodine Deficiency Disorder:". www.malacards.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Chen, ZP; Hetzel, BS (February 2010). "Cretinism revisited". Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 24 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.014. PMID 20172469.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Eastman, Creswell J.; Zimmermann, Michael B. (2000). "The Iodine Deficiency Disorders". Endotext. MDText.com, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- 1 2 "ICD-10 Version:2019". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Salisbury, S (February 2003). "Cretinism: The past, present and future of diagnosis and cure". Paediatrics & child health. 8 (2): 105–6. doi:10.1093/pch/8.2.105. PMID 20019927.

- 1 2 Fanaroff, Avroy A.; Miall, Lawrence; Fanaroff, Jonathan; Lissauer, Tom (12 February 2020). Neonatology at a Glance. John Wiley & Sons. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-119-51320-9. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ↑ "Congenital iodine deficiency syndrome (Concept Id: C3165526) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ↑ Dennison, John; Oxnard, Charles; Obendorf, Peter (25 September 2011). Endemic Cretinism. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4614-0281-7. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ↑ Councilman, W. . (1913). "One". Disease and Its Causes. United States: New York Henry Holt and Company London Williams and Norgate The University Press, Cambridge, USA.

- ↑ "Iodine deficiency may contribute to women's fertility problems". Carolyn Crist, Reuters Health. 2018. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. March 2021

- ↑ Dunn, John T.; Delange, Francois (2001-06-01). "Damaged Reproduction: The Most Important Consequence of Iodine Deficiency". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 86 (6): 2360–2363. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.6.7611. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 11397823. Archived from the original on 2022-06-27. Retrieved 2022-05-29.

- ↑ Kapil, Umesh (December 2007). "Health Consequences of Iodine Deficiency". Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. 7 (3): 267–272. ISSN 2075-051X. PMC 3074887. PMID 21748117.

- ↑ HALPERN, JEAN-PIERRE; BOYAGES, STEVEN C.; MABERLY, GLENDEN F.; COLLINS, JOHN K.; EASTMAN, CRESWELL J.; MORRIS, JOHN G.L. (1991-04-01). "The Neurology of Endemic Cretinism". Brain. 114 (2): 825–841. doi:10.1093/brain/114.2.825. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 2043952. Archived from the original on 2022-06-27. Retrieved 2022-05-29.

- ↑ Chen, Zu-Pei; Hetzel, BS (February 2010). "Cretinism Revisited". Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 24 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.014. PMID 20172469.

- ↑ Chapter 20. The Iodine Deficiency Disorders Archived 2008-03-13 at the Wayback Machine Thyroid Disease Manager. Retrieved: 2011-06-26.

- ↑ Gaitan E, Dunn JT (1992). "Epidemiology of iodine deficiency". Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 3 (5): 170–5. doi:10.1016/1043-2760(92)90167-Y. PMID 18407097. S2CID 43567038.

- ↑ "Medical information;types of dwarfism~r restricted growth". rgauk.org. rgauk. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ↑ Pass, K. A.; Neto, E. C. (2009). "Update: Newborn Screening for Endocrinopathies". Endocrinology & Metabolism Clinics of North America. 38 (4): 827–837. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2009.08.005. PMID 19944295.

- ↑ "Map: Count of Nutrients In Fortification Standards". Global Fortification Data Exchange. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ Chorazy PA, Himelhoch S, Hopwood NJ, Greger NG, Postellon DC (July 1995). "Persistent hypothyroidism in an infant receiving a soy formula: case report and review of the literature". Pediatrics. 96 (1 Pt 1): 148–50. PMID 7596704.

- ↑ Ogbera, Anthonia Okeoghene; Kuku, Sonny Folunrusho (2011). "Epidemiology of thyroid diseases in Africa". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 15 (Suppl2): S82–S88. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.83331. ISSN 2230-8210. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ↑ Venturi, Sebastiano (2014). "Iodine Deficiency in the Population of Montefeltro, A Territory in Central Italy Inside the Regions of Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany and Marche". International Journal of Anthropology. 29 (1–2): 1–12. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ Fergus Fleming, Killing Dragons: The Conquest of the Alps, 2000, Grove Press, p. 179

- ↑ See, for example, William Coxe, "Account of the Vallais, and of the Goiters and Idiots of that Country," Universal Magazine of Knowledge & Pleasure, vol. 67, Dec. 2, 1780.

- ↑ De Maeyer, Lowenstein, Thilly (1979). The Control of Endemic Goitre. Geneva, Switzerland: WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. pp. 9–10. ISBN 92-4-156060-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Hypothyroidism". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ Taylor, Robert B. (2008). White Coat Tales: Medicine's Heroes, Heritage, and Misadventures. New York: Springer. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-387-73080-6. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2022-05-29.

- ↑ "cretin". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 11 December 2005.

- ↑ Brockett, Linus P (Feb 1858). "Cretins And Idiots". The Atlantic Monthly. Archived from the original on 23 January 2005. Retrieved 11 December 2005.

- ↑ Robbins and Cotran – Pathologic basis of disease 8/E. Philadelphia, PA: Sauders Elsevier. 2004.

- ↑ Medvei, VC (1993). The History of Clinical Endocrinology. Pearl River, New York: Parthenon Publishing Group.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |