Congenital toxoplasmosis

| Congenital toxoplasmosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Congenital toxoplasmosis | |

| Symptoms | No symptoms, small or large head, visual loss, mental disability, seizures[1] |

| Complications | Miscarriage, stillbirth[2] |

| Usual onset | Very young babies[1] |

| Causes | Toxoplasma gondii[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, medical imaging[1] |

Congenital toxoplasmosis is toxoplasmosis infection in a newborn baby.[1] The infection may result in miscarriage or stillbirth.[2] Affected newborns initially may have no symptoms.[1] A small or large head is typical.[2] Eye problems such as eye inflammation or strabismus may develop.[1] The liver and spleen may feel large.[1] Other signs and symptoms include small purplish spots, lung inflammation, diarrhoea, yellow eyes, hypothermia, and a rash.[1] Visual loss, mental disability, and seizures may develop.[2] The condition can lead to death of the baby.[1]

The condition is caused by Toxoplasma gondii, as a result of the mother having the infection during or just before pregnancy.[2][3] Diagnosis is with blood tests on the mother and baby.[1] Pregnant women can be tested for IgM and Immunoglobulin G, although this is not always accurate.[1] Ultrasound in pregnancy may reveal signs in the unborn baby, such as hydrocephalus, brain calcifications, pericarditis, large liver and spleen, or large abdomen.[1] The virus may be isolated from a body fluid.[1]

Prevention is by antenatal screening and avoidance of certain foods such as undercooked meats.[1] Where infection occurs in the first 18 weeks of pregnancy, spiramycin can be offered, as long as the baby is not suspected of being affected.[1] Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid can be offered if infection occurs after 18 weeks gestation, or if amniotic fluid is positive by PCR, or if ultrasound findings highly predict congenital toxoplasmosis.[1] Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid, are also used to treat affected babies.[1] The baby may also require prednisolone.[1]

Globally, around 190,000 babies are born with congenital toxoplasmosis each year.[1] Congenital toxoplasmosis was first described in 1923 by Josef Janku in Prague.[4][5]

Signs and symptoms

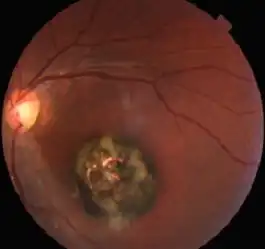

Severe ocular sequelae of congenital toxoplasmosis

Severe ocular sequelae of congenital toxoplasmosis Macular scar

Macular scar

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Montoya, Jose G. (2020). "328. Toxoplasmosis". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 2056-2058. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1. Archived from the original on 2023-09-10. Retrieved 2023-09-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Toxoplasmosis - Disease". www.cdc.gov. CDC-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 February 2019. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ↑ Márquez-Mauricio, Alfredo; Caballero-Ortega, Heriberto; Gómez-Chávez, Fernando (27 June 2023). "Congenital Toxoplasmosis Diagnosis: Current Approaches and New Insights". Acta Parasitologica. doi:10.1007/s11686-023-00693-y. ISSN 1896-1851. PMID 37368128. Archived from the original on 26 August 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ↑ Weiss, Louis M.; Dubey, Jitender. P. (1 July 2009). "Toxoplasmosis: a history of clinical observations". International journal for parasitology. 39 (8): 895–901. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.02.004. ISSN 0020-7519. PMID 19217908. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ↑ Janků, J., 1923. Pathogenesa a pathologická anatomie tak nazvaneho vrozeného kolombu žluté skvrany voku normálné velikem a microphthalmickém s nalezem parasitu v sítnici. Časopis lékařeů českŷck [Pathogenesis and pathologic anatomy of the “congenital coloboma” of the macula lutea in an eye of normal size, with microscopic detection of parasites in the rentna] 62, 1021–1027, 1052–1059, 1081–1085, 1111-111, 1138–1143 (For English translation, see Janků, J., 1959. Cesk. Parasitol. 6, 9–58).