Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

| Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Forestier's disease, senile ankylosing spondylosis, ankylosing hyperostosis |

| |

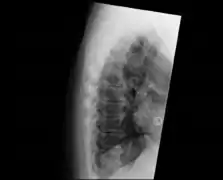

| DISH in an 80 year old female, also with T11 fracture. | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a condition characterized by abnormal calcification/bone formation (hyperostosis) of the soft tissues surrounding the joints of the spine, and also of the peripheral or appendicular skeleton.[1] In the spine, there is bone formation along the anterior longitudinal ligament and sometimes the posterior longitudinal ligament, which may lead to partial or complete fusion of adjacent vertebrae. The facet and sacroiliac joints tend to be uninvolved. The thoracic spine is the most common level involved.[2] In the peripheral skeleton, DISH manifests as a calcific enthesopathy, with pathologic bone formation at sites where ligaments and tendons attach to bone.

Signs and symptoms

The majority of people with DISH are not symptomatic,[3] and the findings are an incidental imaging abnormality.

In some, the x-ray findings may correspond to symptoms of back stiffness with flexion/extension or with mild back pain.[2] Back pain or stiffness may be worse in the morning.[4] Rarely, large anterior cervical spine osteophytes may affect the esophagus or the larynx and cause pain, difficulty swallowing[5][6] or even dyspnea.[7] Similar calcification and ossification may be seen at peripheral entheseal sites, including the shoulder, iliac crest, ischial tuberosity, trochanters of the hip, tibial tuberosities, patellae, and bones of the hands and/or feet.[6]

Cause

The exact cause is unknown. Mechanical, dietary factors and use of some medications (e.g. isotretinoin, etretinate, acitretin and other vitamin A derivatives)[8] may be of significance. There is a correlation between these factors but not a cause or effect. The distinctive radiological feature of DISH is the continuous linear calcification along the antero-medial aspect of the thoracic spine. DISH is usually found in people in their 60s and above, and is extremely rare in people in their 30s and 40s. The disease can spread to any joint of the body, affecting the neck, shoulders, ribs, hips, pelvis, knees, ankles, and hands. The disease is not fatal; however, some associated complications can lead to death. Complications may include paralysis, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), and lung infections.

Although DISH manifests in a similar manner to ankylosing spondylitis, they are separate diseases. Ankylosing spondylitis is a genetic disease with identifiable marks, tends to start showing signs in adolescence or young adulthood, is more likely to affect the lumbar spine, and affects organs. DISH has no indication of a genetic link, is primarily thoracic and does not affect organs other than the lungs, and only indirectly due to the fusion of the rib cage.[9]

Long term treatment of acne with vitamin derived retinoids, such as etretinate[10] and acitretin,[11] have been associated with extraspinal hyperostosis.

Diagnosis

DISH is diagnosed by findings on x-ray studies. Radiographs of the spine will show abnormal bone formation (ossification) along the anterior spinal ligament. The disc spaces, facet and sacroiliac joints remain unaffected. Diagnosis requires confluent ossification of at least four contiguous vertebral bodies.[2] Classically, advanced disease may have "melted candle wax" appearance along the spine on radiographic studies.[12] In some cases, DISH may be manifested as ossification, or enthesis, in other parts of the skeleton.

The calcification and ossification is most common on the right side of the spine. In people with dextrocardia and situs inversus this calcification occurs on the left side.[9]

- Examples of DISH

Confluent ossification of multiple contiguous vertebral bodies in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH)

Confluent ossification of multiple contiguous vertebral bodies in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) "Melted candle wax" appearance of calcification and ossification in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Note the preponderance on the patient's left side (right side of image).

"Melted candle wax" appearance of calcification and ossification in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Note the preponderance on the patient's left side (right side of image). Ectopic calcification and new bone formation in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH)

Ectopic calcification and new bone formation in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in DISH

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in DISH

Treatment

There is limited scientific evidence for the treatment for symptomatic DISH.

Symptoms of pain and stiffness may be treated with conservative measures, analgesic medications (such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), and physical therapy.[13]

In extraordinary cases where calcification or osteophyte formation is causing severe and focal symptoms, such as difficulty swallowing or nerve impingement, surgical intervention may be pursued.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Resnick, D.; Shaul, S. R.; Robins, J. M. (June 1975). "Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH): Forestier's disease with extraspinal manifestations". Radiology. 115 (3): 513–524. doi:10.1148/15.3.513. ISSN 0033-8419. PMID 1129458.

- 1 2 3 Sarwark, John, ed. (2010). "Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis". Essentials of Musculoskeletal Care (4 ed.). Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. ISBN 978-0-89203-579-3.

- ↑ Mader, Reuven; Verlaan, Jorrit-Jan; Buskila, Dan (November 2013). "Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: clinical features and pathogenic mechanisms". Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 9 (12): 741–750. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2013.165. ISSN 1759-4804. PMID 24189840. S2CID 19347729.

- ↑ Resnick, Donald; Shapiro, Robert F.; Wiesner, Kenneth B.; Niwayama, Gen; Utsinger, Peter D.; Shaul, Stephen R. (1978). "Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) [ankylosing hyperostosis of forestier and Rotes-Querol]". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 7 (3): 153–187. doi:10.1016/0049-0172(78)90036-7. PMID 341323.

- ↑ Utsinger PD (August 1985). "Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis". Clinics in Rheumatic Diseases. 11 (2): 325–51. doi:10.1016/S0307-742X(21)00544-0. PMID 3899489.

- 1 2 Mata S, Fortin PR, Fitzcharles MA, Starr MR, Joseph L, Watts CS, Gore B, Rosenberg E, Chhem RK, Esdaile JM (March 1997). "A controlled study of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. Clinical features and functional status". Medicine. 76 (2): 104–17. doi:10.1097/00005792-199703000-00003. PMID 9100738. S2CID 5950196.

- ↑ Psychogios, Georgios; Jering, Monika; Zenk, Johannes (2018). "Cervical Hyperostosis Leading to Dyspnea, Aspiration and Dysphagia: Strategies to Improve Patient Management". Frontiers in Surgery. 5: 33. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2018.00033. ISSN 2296-875X. PMC 5928235. PMID 29740589.

- ↑ Nascimento; et al. (2014). "Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: A review". Surg Neurol Int. 5 (Suppl 3): S122–S125. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.130675. PMC 4023007. PMID 24843807.

- 1 2 Forestier J, Lagier R (January 1971). "Ankylosing hyperostosis of the spine". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 74: 65–83. doi:10.1097/00003086-197101000-00009. PMID 4993095.

- ↑ DiGiovanna JJ, Helfgott RK, Gerber LH, Peck GL (November 1986). "Extraspinal tendon and ligament calcification associated with long-term therapy with etretinate". The New England Journal of Medicine. 315 (19): 1177–82. doi:10.1056/NEJM198611063151901. PMID 3463863.

- ↑ DiGiovanna JJ (November 2001). "Isotretinoin effects on bone". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 45 (5): S176–82. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.113721. PMID 11606950.

- ↑ Waldron, T. "Paleopathology". Cambridge University Press, 2009, p. 73.

- ↑ Al-Herz A, Snip JP, Clark B, Esdaile JM (February 2008). "Exercise therapy for patients with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis". Clinical Rheumatology. 27 (2): 207–10. doi:10.1007/s10067-007-0693-z. PMID 17885726. S2CID 13481354.

- ↑ Castellano DM, Sinacori JT, Karakla DW (February 2006). "Stridor and dysphagia in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH)". The Laryngoscope. 116 (2): 341–4. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000197936.48414.fa. ISSN 0023-852X. PMID 16467731. S2CID 30733962.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. |