Pubic lice

| Pubic lice | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Pediculosis pubis, crabs, phthiriasis, phthiriasis pubis | |

| |

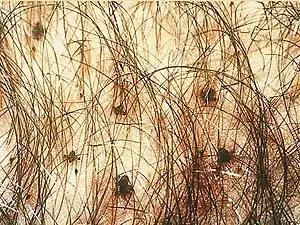

| Pubic lice in genital area | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Itch, grey-blue marks, visible lice and nits[1] |

| Complications | Bacterial skin infection[2] |

| Causes | Pubic louse spread by sex or clothing[3] |

| Risk factors | Crowded situations[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Seeing the lice[5] |

| Treatment | Permethrin or pyrethrin lotion, combing to remove nits[4] |

| Frequency | ~2%[6] |

Pubic lice, also known as crabs or pediculosis pubis, is an infestation by the pubic louse.[1][7] It most commonly occurs on pubic hair, though other large diameter hair such as armpit, beard, eyebrow, or eyelash may be involved.[4][8] The main symptom is itching in the groin area.[9] There may be grey-blue discolouration at the feeding site, blood stains, and crusts and eggs (nits) and live lice may be seen.[1][4] Complications may include a secondary bacterial infection as a result of scratching.[2]

The cause is the pubic louse, Pthirus pubis, a wingless insect which feeds on human blood and lays its eggs on hair or clothing.[3][4] It is usually spread during sex, but can be transmitted via bedding, clothing, or towels.[4] It is more common in crowded conditions.[4] Diagnosis is by finding the nits or live lice, either directly or with a magnifying glass.[10] When infested the typical number of lice present is about a dozen.[8] Testing for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is recommended.[5]

First line treatment is with either permethrin or pyrethrin combined with piperonyl butoxide applied to the skin.[4] Two rounds of treatment at least a week apart is usually required to kill newly hatched lice.[8] Other treatments that may be used include the application of malathion or taking ivermectin by mouth.[1] Washing bedding and clothing in hot water kills the lice and further spread can be prevented by avoiding sexual contact until better.[11] Eggs may be removed by combing pubic hair with a comb dipped in vinegar.[7] Sexual partners should also be treated.[7]

Worldwide, the condition affects about 2% of the population.[6] Infestations with pubic lice are found in all parts of the world, occurs in all ethnic groups, and all levels of society.[7] Adults are more commonly affected than children.[2] Pubic lice have been described in ancient history with cases involving soldiers in the second century.[12][13]

Signs and symptoms

The onset of symptoms is typically three weeks after the first infestation of lice and is mainly an intense itch in the pubic area and groin, particularly at night, resulting from an allergic reaction to the saliva of feeding lice.[4][14][15] In some infestations, a characteristic grey-blue or slate coloration macule appears (maculae caeruleae) at the feeding site, which may last for days. Nits or live lice may be seen crawling on the skin.[7][16][17] It may be noticed as a black powder in the underwear.[15]

Scratch marks, crusting, scarring, rust-coloured faecal material, blood stained underwear and secondary bacterial infection may sometimes be seen. Large lymph nodes in the groin and armpits may be felt.[4] Some people with pubic lice infestation may not have any symptoms.[17]

Pubic lice lay eggs on hair shaft

Pubic lice lay eggs on hair shaft Pubic lice on the abdomen

Pubic lice on the abdomen Pubic lice on the eyelashes

Pubic lice on the eyelashes

Complications

Complications are usually as a result of persistent scratching and include thickening of the skin, darkened skin, and secondary bacterial infection including impetigo, conjunctivitis and blepharitis.[4]

Causes

Spread

Pubic lice are usually spread from one person to another during vaginal, oral or anal sex.[14] In some circumstances transmission can occur via bedding, clothing and towels, and the lice spread more easily in crowded conditions where the distance between people is close.[4] Infestation in a young child or teenager may indicate sexual abuse.[7] Condoms do not offer protection against pubic lice and it is not spread by toilet seats.[1][15]

Crab louse

Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis) have three stages: the egg (also called a nit), the nymph, and the adult. They can be hard to see and are found firmly attached to the hair shaft. They are oval and usually yellow to white. Pubic lice nits take about 6–10 days to hatch. The nymph is an immature louse that hatches from the nit (egg). A nymph looks like an adult pubic louse but it is smaller. Pubic lice nymphs take about 2–3 weeks after hatching to mature into adults capable of reproducing. To live, a nymph must feed on blood. The adult pubic louse resembles a miniature crab when viewed through a strong magnifying glass. Pubic lice have six legs; their two front legs are very large and look like the pincher claws of a crab—thus the nickname "crabs." Pubic lice are tan to grayish-white in color. Females lay nits and are usually larger than males.[7] To live, lice must feed on blood. If the louse falls off a person, it dies within 1–2 days. Eggs (nits) are laid on a hair shaft. Females will lay approximately 30 eggs during their 3–4 week life span. Eggs hatch after about a week and become nymphs, which look like smaller versions of the adults. The nymphs undergo three molts before becoming adults. Adults are 1.5–2.0 mm long and flattened. They are much broader in comparison to head and body lice. Adults are found only on the human host and require human blood to survive. Pubic lice are transmitted from person to person most-commonly via sexual contact, although fomites (bedding, clothing) may play a minor role in their transmission.[14][3]

Diagnosis

A pubic louse infestation is usually diagnosed by carefully examining pubic hair for nits, nymphs, and adult lice.[14] Lice and nits can be removed either with forceps or by cutting the infested hair with scissors (with the exception of an infestation of the eye area). A magnifying glass or a stereo-microscope can be used for identification.[8] Adult lice light up when under a Wood's lamp.[4]

Testing for other sexually transmitted infections is recommended in those who are infested with pubic lice.[14][4]

Treatment

Pubic lice can be treated at home. Available treatments may vary from country to country and include mainly permethrin containing creams and lotions applied to cool dry skin.[1]

Combing pubic hair with a fine-toothed comb after applying vinegar directly to skin or dipping the comb in vinegar, can remove nits.[4][16] It is recommended to wash bedding, clothing and towels in hot water or preferably in a washing machine at 50°C or higher. When this is not possible, the clothing can be stored in a sealed plastic bag for at least three days.[1][18] Re-infestation can be prevented by wearing clean underwear at the start of treatment and after completing treatment.[1] Shaving the affected hair is not essential.[1]

First line

The preferable first line treatment is topical permethrin 1% cream, which can be bought over the counter without a prescription. It is applied to the areas affected by pubic lice and washed off after 10 minutes.[18] It is also available at the strength of 5%.[19] An alternative is the combination of pyrethrins and piperonyl butoxide.[18] These medications are safe and effective when used exactly according to the instructions in the package or on the label.[9] To kill newly hatched lice, the treatment can be repeated within the following seven to ten days.[8][20]

Applying 0.5% malathion lotion to affected areas and washed off after 12 hours is an alternative to permethrin.[18] Another option is oral ivermectin at a dose of 250 ug/kg and repeated after two weeks.[18]

Other treatments

Lindane is still used in a shampoo form in some non-European countries. Its licence was withdrawn by the European Medicines Agency in 2008.[1] It may be considered as a last resort in some people who show resistance to other treatments, but is not recommended to be used for a second round of treatment.[14][1] Lindane is not recommended in pregnant and breastfeeding women, children under the age of two years, and people who have extensive dermatitis.[14][9] The FDA warns against use in people with a history of uncontrolled seizure disorders and cautious use in infants, children, the elderly, and individuals with other skin conditions (e.g., atopic dermatitis, psoriasis) and in those who weigh less than 110 lbs (50 kg).[9][21] Carbaryl has been used since 1976 but found to have the potential to cause cancer in rodents and not to be as effective as previously thought. It is either not used at all or its use is restricted.[1][22]

Sexual partners should be evaluated and treated, and sexual contact should be avoided until all partners are better. Because of the strong association between the presence of pubic lice and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), affected people require investigation for other STIs.[9]

Eyes

Infestation of the eyes is treated differently to other parts of the body. Lice can be removed with forceps or by removing or trimming the lashes.[23] Eyelashes may be treated with a gentle petroleum jelly.[23]

Epidemiology

Infestation with pubic lice is found in all parts of the world, occurs in all ethnic groups and all levels of society.[2]

Current worldwide prevalence has been very approximately estimated at two percent of the human population. Accurate numbers are difficult to acquire, because pubic lice infestations are not considered a reportable condition by many governments. Many cases are self-treated or treated discreetly by personal physicians, which further adds to the difficulty of producing accurate statistics.[6]

It has been reported that the trend of pubic hair removal has led to the destruction of the natural habitat of the crab louse populations in some parts of the world, thereby reducing the incidence of the disease.[1][24][25]

History

Pubic lice have existed for millions of years.[26] Infestations by pubic lice have been described since ancient history with cases involving soldiers in the second century.[12][13] Linnaeus was first to describe and name the pubic louse in 1758, when he called it Pediculus pubis. The disease is spelled with phth, but the scientific name of the louse Pthirus pubis is spelled with pth (an etymologically incorrect spelling that was nonetheless officially adopted in 1958).[27]

Names

Infestation with pubic lice is also called "phthiriasis" or "phthiriasis pubis", while infestation of eyelashes with pubic lice is called phthiriasis palpebrarum or pediculosis ciliarum.[28]

Other animals

Humans are the only known hosts of this parasite,[16] although a closely related species, Pthirus gorillae, infects gorilla populations.[29]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Salavastru, C. M.; Chosidow, O.; Janier, M.; Tiplica, G. S. (2017). "European guideline for the management of pediculosis pubis". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 31 (9): 1425–1428. doi:10.1111/jdv.14420. ISSN 1468-3083.

- 1 2 3 4 "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) - Lice - Pubic: Epidemiology & Risk Factors". www.cdc.gov. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) - Lice - Pubic: Biology". www.cdc.gov. 24 June 2019. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Part II. Managing infectious diseases: Pediculosis". Lippincott's Guide to Infectious Diseases. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-60547-975-0. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- 1 2 Bragg, BN; Simon, LV (January 2020). "Pediculosis". PMID 29262055.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 Alice L. Anderson; Elizabeth Chaney (2009). "Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis): history, biology and treatment vs. knowledge and beliefs of US College students". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (2): 592–600. doi:10.3390/ijerph6020592. PMC 2672365. PMID 19440402.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) - Lice - Pubic: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". www.cdc.gov. 17 September 2020. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 4 5 Williams gynecology. Hoffman, Barbara L., Williams, J. Whitridge (John Whitridge), 1866-1931. (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2012. pp. 90–91. ISBN 9780071716727. OCLC 779244257. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) - Lice - Pubic: Disease". www.cdc.gov. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) - Lice - Pubic: Diagnosis". www.cdc.gov. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) - Lice - Pubic: Treatment". www.cdc.gov. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- 1 2 Gross, Gerd; Tyring, Stephen K. (2011). Sexually Transmitted Infections and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-642-14663-3. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- 1 2 Middleberg, Maurice I. (2006). Promoting Reproductive Security in Developing Countries. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-306-47935-9. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 P. A. Leone (2007). "Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 (Suppl. 3): S153–S159. doi:10.1086/511428. PMID 17342668.

- 1 2 3 "Pubic lice". nhs.uk. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Pubic lice: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 O'Donel Alexander, John (2012). "5. Infestation with Anoplura- Lice". Arthropods and Human Skin. Berlin: Springer Verlag. pp. 29–53. ISBN 978-1-4471-1358-4. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Ectoparasitic Infections, Pediculosis Pubis (Treatment)". www.cdc.gov. 1 January 2019. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines: 21st list. WHO. 2019. p. 38.

- ↑ Buttaravoli, Philip; Hudson, Page (2012). "178. Pediculosis (lice, crabs)". In Philip Buttaravoli (ed.). Minor Emergencies E-Book. Stephen M. Leffler (Third ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 701. ISBN 978-0-323-07909-9. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ↑ "Lindane Shampoo, USP, 1%" Archived 23 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine. FDA.

- ↑ Sangaré, Abdoul Karim; Doumbo, Ogobara K.; Raoult, Didier (2016). "Management and Treatment of Human Lice". BioMed Research International. 2016. doi:10.1155/2016/8962685. ISSN 2314-6133. PMC 4978820. PMID 27529073. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- 1 2 Saw, P. J.; Leonard, Jonathan (2016). "109. Dermatoses of the eye, eyelids and eyebrows". In Griffiths, Christopher; Barker, Jonathan; Bleiker, Tanya O.; Chalmers, Robert; Creamer, Daniel (eds.). Rook's Textbook of Dermatology, 4 Volume Set. Vol. 3. John Wiley & Sons. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-118-44119-0. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ↑ N. R. Armstrong; J. D. Wilson (2006). "Did the "Brazilian" kill the pubic louse?". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 82 (3): 265–266. doi:10.1136/sti.2005.018671. PMC 2564756. PMID 16731684.

- ↑ Bloomberg: Brazilian bikini waxes make crab lice endangered species Archived 29 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, published 13 January 2013, retrieved 14 January 2013

- ↑ Meinking, Terri; Taplin, David; Vicaria, Maureen (2011). "27. Infestations". In Schachner, Lawrence A.; Hansen, Ronald C. (eds.). Pediatric Dermatology E-Book (4th ed.). Elsevier. p. 1535. ISBN 978-0-7234-3540-2. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ "Taxonomy of Human Lice | Phthiraptera.info". phthiraptera.info. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ N. P. Manjunatha; G. R. Jayamanne; S. P. Desai; T. R. Moss; J. Lalik; A. Woodland (2006). "Pediculosis pubis: presentation to ophthalmologist as pthriasis palpebrarum associated with corneal epithelial keratitis". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 17 (6): 424–426. doi:10.1258/095646206777323445. PMID 16734970.

- ↑ Robin A. Weiss (2009). "Apes, lice and prehistory". Journal of Biology. 8 (2): 20. doi:10.1186/jbiol114. PMC 2687769. PMID 19232074.

External links

- Crab louse Archived 13 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine on the UF / Institute of Food and Agriculture

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |