Pleconaril

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intranasal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 70% (oral) |

| Protein binding | >99% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Excretion | <1% excreted unchanged in urine |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.208.947 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

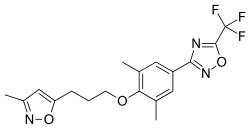

| Formula | C18H18F3N3O3 |

| Molar mass | 381.355 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Pleconaril (Picovir[1]) is an antiviral drug that was being developed by Schering-Plough for prevention of asthma exacerbations and common cold symptoms in patients exposed to picornavirus respiratory infections.[2] Pleconaril, administered either orally or intranasally, is active against viruses in the Picornaviridae family, including Enterovirus[3] and Rhinovirus.[4] It has shown useful activity against the dangerous enterovirus D68.[5]

History

Pleconaril was originally developed by Sanofi-Aventis, and licensed to ViroPharma in 1997. ViroPharma developed it further, and submitted a New Drug Application to the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2001. The application was rejected, citing safety concerns; and ViroPharma re-licensed it to Schering-Plough in 2003. The Phase II clinical trial was completed in 2007.[2] A pleconaril intranasal spray had reached phase II clinical trial for the treatment of the common cold symptoms and asthma complications. However, the results have yet to be reported.[6]

Mechanism of action

In enteroviruses, Pleconaril prevents the virus from exposing its RNA, and in rhinoviruses Pleconaril prevents the virus from attaching itself to the host cell.[7] Human rhinoviruses (HRVs) contain four structural proteins labeled VP1-VP4. Proteins VP1, VP2 and VP3 are eight stranded anti-parallel β-barrels. VP4 is an extended polypeptide chain on the viral capsid inner surface.[8] Pleconaril binds to a hydrophobic pocket in the VP1 protein. Pleconaril has been shown in viral assembly to associate with viral particles.[9] Through noncovalent, hydrophobic interactions compounds can bind to the hydrophobic pocket.[10] Amino acids in positions Tyr152 and Val191 are a part of the VP1 drug binding pocket.[8]

In Coxsackievirus, Pleconaril efficiency correlates to the susceptibility of CVB3 with the amino acid at position 1092 in the hydrophobic pocket.[11] Amino acid 1092 is in close proximity to the central ring of capsid binders.[12] The binding of pleconaril in the hydrophobic pocket creates conformational changes, which increases the rigidity of the virion and decreases the virions' ability to interact with its receptor.[13] Drugs bind with the methylisoxazole ring close to the entrance pocket in VP1, the 3-fluromethyl oxadiazole ring at the end of the pocket and the phenyl ring in the center of the pocket.[6]

Clinical trials

The results of two randomized, double blind, placebo studies found Pleconaril treatment could benefit patients suffering from colds due to picornaviruses.[14] Participants in the studies were healthy adults from Canada and the United States, with self-diagnosed colds that had occurred within 24 hours of trial enrollment. Participants were randomly given a placebo or two 200 mg tablets to take three times daily for five days. To increase absorption it was recommended to be taken after a meal.[14] To monitor the effectiveness of Pleconaril, participants recorded the severity of their symptoms and nasal mucosal samples were obtained at enrollment, day 3, day 6 and day 18. The two studies had a total of 2096 participants and more than 90% (1945) completed the trial. The most common reason for a participant not finishing the trial was an adverse event. Pleconaril treatment showed a reduction in nose blowing, sleep disturbance, and less cold medication used.[14]

Another study showed over 87% of virus isolates in cell culture were inhibited by pleconaril.[9] Virus variants were detected in 0.7% of the placebo group and 10.7% of the pleconaril group. Of the two isolates a subject from the placebo group had a resistant virus in cell culture to pleconaril. The other strain was susceptible to the drug. The pleconaril group had 21 virus strains, which remained susceptible. Resistance strains were found in 7 pleconaril patients.[9]

A Phase II study that used an intranasal formulation of pleconaril failed to show a statistically significant result for either of its two primary efficacy endpoints, percentage of participants with rhinovirus PCR-positive colds and percentage of participants with asthma exacerbations together with rhinovirus-positive PCR.[15]

Resistance

In human rhinoviruses mutations in amino acids at positions 152 and 191 decrease the efficiency of pleconaril. The resistant HRV have phenylalanine at position 152 and leucine at position 191. In vitro studies have shown resistance to pleconaril may emerge. The wild type resistance frequency to pleconaril was about 5×10−5. Coxsackievirus B3(CVB3) strain Nancy and other mutants carry amino acid substitutions at position 1092 of Ile1092->Leu1092 or Ile1092->Met in VP1. The Ile->Leu mutation causes complete resistance to pleconaril. The study found resistance of CVB3 to pleconaril can be overcome by substitution of the central phenyl group. Methyl and bromine substitutions created an increase of pleconaril activity towards sensitive and resistant strains. Amino acid substitutions in the hydrophobic pocket and receptor binding region of viral capsid proteins were shown to have an effect against the sensitivity of capsid binding antivirals.[6]

Side effects of pleconaril

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration rejected pleconaril in 2002 due to the side effects. The most commonly reported side effects were mild to moderate headache, diarrhea, and nausea.[14] Some women were having symptoms of spotting in between periods. Menstrual irregularities were reported by 3.5% of the 320 pleconaril treated women using oral contraceptives and by none of the 291 placebo treated women.[14] In the clinical trial two women became pregnant due to the drug interfering with hormonal birth control by activation of cytochrome P-450 3A enzymes. Other patients have described painful nasal inflammation.[16]

References

- ↑ "Pharma News - Latest Pharma & Pharmaceutical news & updates".

- 1 2 "Effects of Pleconaril Nasal Spray on Common Cold Symptoms and Asthma Exacerbations Following Rhinovirus Exposure (Study P04295AM2)". ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Institutes of Health. March 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ↑ Pevear D, Tull T, Seipel M, Groarke J (1999). "Activity of pleconaril against enteroviruses". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 43 (9): 2109–15. doi:10.1128/AAC.43.9.2109. PMC 89431. PMID 10471549.

- ↑ Ronald B. Turner; J. Owen Hendley (2005). "Virucidal hand treatments for prevention of rhinovirus infection". J Antimicrob Chemother. 56 (5): 805–807. doi:10.1093/jac/dki329. PMID 16159927.

- ↑ Liu, Y; et al. (2015). "Structure and inhibition of EV-D68, a virus that causes respiratory illness in children". Science. 347 (6217): 71–74. Bibcode:2015Sci...347...71L. doi:10.1126/science.1261962. PMC 4307789. PMID 25554786.

- 1 2 3 Schmidtke, Michaela; Wutzler, Peter; Zieger, Romy; Riabova, Olga B.; Makarov, Vadim A. (2009). "New pleconaril and [(biphenyloxy)propyl]isoxazole derivatives with substitutions in the central ring exhibit antiviral activity against pleconaril-resistant coxsackievirus B3". Antiviral Research. 81 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2008.09.002. PMID 18840470.

- ↑ Florea N, Maglio D, Nicolau D (2003). "Pleconaril, a novel antipicornaviral agent". Pharmacotherapy. 23 (3): 339–48. doi:10.1592/phco.23.3.339.32099. PMC 7168037. PMID 12627933. Free full text with registration

- 1 2 Ledford, Rebecca M.; Collett, Marc S.; Pevear, Daniel C. (1 December 2005). "Insights into the genetic basis for natural phenotypic resistance of human rhinoviruses to pleconaril". Antiviral Research. 68 (3): 135–138. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.08.003. PMID 16199099.

- 1 2 3 Pevear, D. C.; Hayden, F. G.; Demenczuk, T. M.; Barone, L. R.; McKinlay, M. A.; Collett, M. S. (26 October 2005). "Relationship of Pleconaril Susceptibility and Clinical Outcomes in Treatment of Common Colds Caused by Rhinoviruses". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 49 (11): 4492–4499. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.11.4492-4499.2005. PMC 1280128. PMID 16251287.

- ↑ Braun, Heike; Makarov, Vadim A.; Riabova, Olga B.; Wutzler, Peter; Schmidtke, Michaela (2011). "Amino Acid Substitutions At Residue 207 of Viral Capsid Protein 1 (VP1) Confer Pleconaril Resistance in Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3)". Antiviral Research. 90 (2): A54–A55. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.03.100.

- ↑ Schmidtke, Michaela; Wutzler, Peter; Zieger, Romy; Riabova, Olga B.; Makarov, Vadim A. (2009). "New pleconaril and [(biphenyloxy)propyl]isoxazole derivatives with substitutions in the central ring exhibit antiviral activity against pleconaril-resistant coxsackievirus B3". Antiviral Research. 81 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.09.002. PMID 18840470.

- ↑ Thibaut, Hendrik Jan; De Palma, Armando M.; Neyts, Johan (2012). "Combating enterovirus replication: State-of-the-art on antiviral research". Biochemical Pharmacology. 83 (2): 185–192. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2011.08.016. PMID 21889497.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hayden, F.G.; Herrington, D.T.; Coats, T.L.; Kim, K.; Cooper, E.C.; Villano, S.A.; Liu, S.; Hudson, S.; Pevear, D.C.; Collett, M.; McKinlay, M. (Jun 15, 2003). "Efficacy and safety of oral pleconaril for treatment of colds due to picornaviruses in adults: results of 2 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials". Pleconaril Respiratory Infection Study, Group. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 36 (12): 1523–32. doi:10.1086/375069. PMC 7199898. PMID 12802751.

- ↑ National Institutes of Health. Effects of Pleconaril Nasal Spray on Common Cold Symptoms and Asthma Exacerbations Following Rhinovirus Exposure (Study P04295AM2). Clinical Trials.gov. Available at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/gui/show/NCT00394914. Accessed: July 20, 2015

- ↑ Greenwood, Veronique (2011). "Curing the Common Cold". Scientific American. 304 (1): 30–1. Bibcode:2011SciAm.304a..30G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0111-30. PMID 21265321. Retrieved 2013-03-25.