Ropivacaine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /roʊˈpɪvəkeɪn/ |

| Trade names | Naropin |

| Other names | Ropivacaine hydrochloride |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Local anesthetic (amide)[1] |

| Side effects | Nausea, slow heart rate, low blood pressure, pain, itchiness[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Parenteral |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 87%–98% (epidural) |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP1A2-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 1.6–6 hours (varies with administration route) |

| Excretion | Kidney 86% |

| Chemical and physical data | |

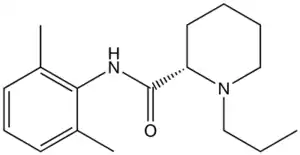

| Formula | C17H26N2O |

| Molar mass | 274.408 g·mol−1 |

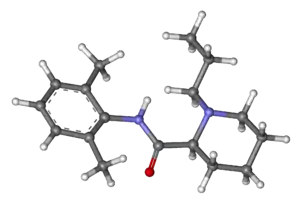

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 144 to 146 °C (291 to 295 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Ropivacaine, sold under the brand name Naropin, is a local anesthetic.[1] It may be injected into an area, used for a nerve block, or given during an epidural.[1]

Common side effects include nausea, slow heart rate, low blood pressure, pain and itchiness.[1] Other side effects may include arrhythmia and abnormal sensation.[2] Use during pregnancy appears to be safe for the baby but has not been well studied.[3] It appears to have less heart and neurological side effects.[1] It belonging to amide group.[1]

Ropivacaine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1996.[1] It is available as a generic medication.[2] In the United States a 200 ml of 0.2% solution costs about 100 USD.[4] This amount in the United Kingdom costs about £14.[2]

Contraindications

Ropivacaine is contraindicated for intravenous regional anaesthesia (IVRA). However, new data suggested both ropivacaine (1.2-1.8 mg/kg in 40ml) and levobupivacaine (40 ml of 0.125% solution) be used, because they have less cardiovascular and central nervous system toxicity than racemic bupivacaine.[5]

Side effects

Side effects are rare when it is administered correctly. Most ADRs relate to administration technique (resulting in systemic exposure) or pharmacological effects of anesthesia, however allergic reactions can rarely occur.

Systemic exposure to excessive quantities of ropivacaine mainly result in central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular effects – CNS effects usually occur at lower blood plasma concentrations and additional cardiovascular effects present at higher concentrations, though cardiovascular collapse may also occur with low concentrations. CNS effects may include CNS excitation (nervousness, tingling around the mouth, tinnitus, tremor, dizziness, blurred vision, seizures followed by depression (drowsiness, loss of consciousness), respiratory depression and apnea). Cardiovascular effects include hypotension, bradycardia, arrhythmias, and/or cardiac arrest – some of which may be due to hypoxemia secondary to respiratory depression.[6]

Cartilage

Ropivacaine is toxic to cartilage and their intra-articular infusions can lead to Postarthroscopic glenohumeral chondrolysis.[7]

Overdose

As for bupivacaine, Celepid, a commonly available intravenous lipid emulsion, can be effective in treating severe cardiotoxicity secondary to local anaesthetic overdose in animal experiments[8] and in humans in a process called lipid rescue.[9][10][11]

History

Ropivacaine was developed after bupivacaine was noted to be associated with cardiac arrest, particularly in pregnant women. Ropivacaine was found to have less cardiotoxicity than bupivacaine in animal models.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Ropivacaine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 1428. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ "Ropivacaine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ↑ "Naropin Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ↑ (Basic of Anesthesia, Robert Stoelting, page 289)

- ↑ Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3

- ↑ Gulihar A, Robati S, Twaij H, Salih A, Taylor GJ (December 2015). "Articular cartilage and local anaesthetic: A systematic review of the current literature". Journal of Orthopaedics. 12 (Suppl 2): S200-10. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2015.10.005. PMC 4796530. PMID 27047224.

- ↑ Weinberg G, Ripper R, Feinstein DL, Hoffman W (2003). "Lipid emulsion infusion rescues dogs from bupivacaine-induced cardiac toxicity". Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 28 (3): 198–202. doi:10.1053/rapm.2003.50041. PMID 12772136. S2CID 6247454.

- ↑ Picard J, Meek T (February 2006). "Lipid emulsion to treat overdose of local anaesthetic: the gift of the glob". Anaesthesia. 61 (2): 107–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04494.x. PMID 16430560. S2CID 29843241.

- ↑ Rosenblatt MA, Abel M, Fischer GW, Itzkovich CJ, Eisenkraft JB (July 2006). "Successful use of a 20% lipid emulsion to resuscitate a patient after a presumed bupivacaine-related cardiac arrest". Anesthesiology. 105 (1): 217–8. doi:10.1097/00000542-200607000-00033. PMID 16810015.

- ↑ Litz RJ, Popp M, Stehr SN, Koch T (August 2006). "Successful resuscitation of a patient with ropivacaine-induced asystole after axillary plexus block using lipid infusion". Anaesthesia. 61 (8): 800–1. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04740.x. PMID 16867094. S2CID 43125067.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

- "Ropivacaine hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-10-26. Retrieved 2020-10-22.