Silicosis

| Silicosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Miner's phthisis, Grinder's asthma, Potter's rot[1] pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis[2][3] | |

| |

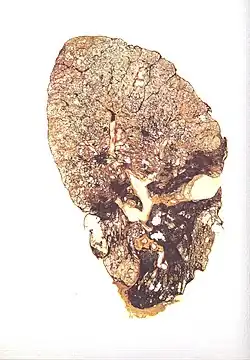

| Slice of a lung affected by silicosis | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Differential diagnosis | Pulmonary talcosis, coal workers' pneumoconiosis |

Silicosis is a form of occupational lung disease caused by inhalation of crystalline silica dust. It is marked by inflammation and scarring in the form of nodular lesions in the upper lobes of the lungs. It is a type of pneumoconiosis.[4] Silicosis (particularly the acute form) is characterized by shortness of breath, cough, fever, and cyanosis (bluish skin). It may often be misdiagnosed as pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs), pneumonia, or tuberculosis. Using workplace controls, silicosis is almost always a preventable disease.[5]

Silicosis resulted in at least 43,000 deaths globally in 2013, down from at least 50,000 deaths in 1990.[6]

The name silicosis (from the Latin silex, or flint) was originally used in 1870 by Achille Visconti (1836–1911), prosector in the Ospedale Maggiore of Milan.[7] The recognition of respiratory problems from breathing in dust dates to ancient Greeks and Romans.[8] Agricola, in the mid-16th century, wrote about lung problems from dust inhalation in miners. In 1713, Bernardino Ramazzini noted asthmatic symptoms and sand-like substances in the lungs of stone cutters. Less than 10 years after its introduction, in 1720, as a raw material to the British ceramics industry the negative effects of milled calcined flint on the lungs of workers had been noted.[9] With industrialization, as opposed to hand tools, came increased production of dust. The pneumatic hammer drill was introduced in 1897 and sandblasting was introduced in about 1904,[10] both significantly contributing to the increased prevalence of silicosis. In 1938, the United States Department of Labor, led by then Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, produced a video titled 'Stop Silicosis Archived 2023-04-26 at the Wayback Machine' to discuss the results of a year-long study done concerning a rise in the number of silicosis cases across the United States.[11]

Signs and symptoms

Because chronic silicosis is slow to develop, signs and symptoms may not appear until years after exposure.[12] Signs and symptoms include:

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath) exacerbated by exertion

- Cough, often persistent and sometimes severe

- Fatigue

- Tachypnea (rapid breathing) which is often labored,

- Loss of appetite and weight loss

- Chest pain

- Fever

- Gradual darkening of skin (blue skin)

- Gradual dark shallow rifts in nails eventually leading to cracks as protein fibers within nail beds are destroyed.

In advanced cases, the following may also occur:

- Cyanosis, pallor along upper parts of body (blue skin)

- Cor pulmonale (right ventricle heart disease)

- Respiratory insufficiency

Patients with silicosis are particularly susceptible to tuberculosis (TB) infection—known as silicotuberculosis. The reason for the increased risk—3 fold increased incidence—is not well understood. It is thought that silica damages pulmonary macrophages, inhibiting their ability to kill mycobacteria. Even workers with prolonged silica exposure, but without silicosis, are at a similarly increased risk for TB.[13]

Pulmonary complications of silicosis also include chronic bronchitis and airflow limitation (indistinguishable from that caused by smoking), non-tuberculous Mycobacterium infection, fungal lung infection, compensatory emphysema, and pneumothorax. There are some data revealing an association between silicosis and certain autoimmune diseases, including nephritis, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus, especially in acute or accelerated silicosis.[14]

In 1996, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) reviewed the medical data and classified crystalline silica as "carcinogenic to humans." The risk was best seen in cases with underlying silicosis, with relative risks for lung cancer of 2–4. Numerous subsequent studies have been published confirming this risk. In 2006, Pelucchi et al. concluded, "The silicosis-cancer association is now established, in agreement with other studies and meta-analysis."[15]

Pathophysiology

When small silica dust particles are inhaled, they can embed themselves deeply into the tiny alveolar sacs and ducts in the lungs, where oxygen and carbon dioxide gases are exchanged. There, the lungs cannot clear out the dust by mucus or coughing.

When fine particles of crystalline silica dust are deposited in the lungs, macrophages that ingest the dust particles will set off an inflammatory response by releasing tumor necrosis factors, interleukin-1, leukotriene B4 and other cytokines. In turn, these stimulate fibroblasts to proliferate and produce collagen around the silica particle, thus resulting in fibrosis and the formation of the nodular lesions. The inflammatory effects of crystalline silica are apparently mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome.[16]

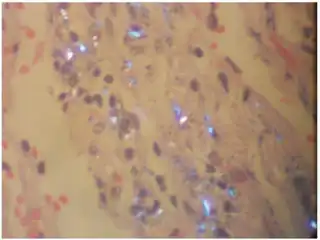

Characteristic lung tissue pathology in nodular silicosis consists of fibrotic nodules with concentric "onion-skinned" arrangement of collagen fibers, central hyalinization, and a cellular peripheral zone, with lightly birefringent particles seen under polarized light. The silicotic nodule represents a specific tissue response to crystalline silica.[10] In acute silicosis, microscopic pathology shows a periodic acid-Schiff positive alveolar exudate (alveolar lipoproteinosis) and a cellular infiltrate of the alveolar walls.[17]

Silica

Silicon (Si) is the second most common element in the Earth's crust (oxygen is the most common). The compound silica, also known as silicon dioxide (SiO2), is formed from silicon and oxygen atoms. Since oxygen and silicon make up about 75% of the Earth's crust, the compound silica is quite common. It is found in many rocks, such as granite, sandstone, gneiss and slate, and in some metallic ores. Silica can be a main component of sand. It can also be in soil, mortar, plaster, and shingles. The cutting, breaking, crushing, drilling, grinding, or abrasive blasting of these materials may produce fine to ultra fine airborne silica dust.

Silica occurs in three forms: crystalline, microcrystalline (or cryptocrystalline) and amorphous (non-crystalline). "Free" silica is composed of pure silicon dioxide, not combined with other elements, whereas silicates (e.g., talc, asbestos, and mica) are SiO2 combined with an appreciable portion of cations.

- Crystalline silica exists in seven different forms (polymorphs), depending upon the temperature of formation. The main three polymorphs are quartz, cristobalite, and tridymite. Quartz is the second most common mineral in the world (next to feldspar).[18]

- Microcrystalline silica consists of minute quartz crystals bonded together with amorphous silica. Examples include flint and chert.

- Amorphous silica consists of kieselgur (diatomite), from the skeletons of diatoms, and vitreous silica, produced by heating and then rapid cooling of crystalline silica. Amorphous silica is less toxic than crystalline, but not biologically inert, and diatomite, when heated, can convert to tridymite or cristobalite.

Silica flour is nearly pure SiO2 finely ground. Silica flour has been used as a polisher or buffer, as well as paint extender, abrasive, and filler for cosmetics. Silica flour has been associated with all types of silicosis, including acute silicosis.

Silicosis is due to deposition of fine respirable dust (less than 10 micrometers in diameter) containing crystalline silicon dioxide in the form of alpha-quartz, cristobalite, or tridymite.

Diagnosis

There are three key elements to the diagnosis of silicosis. First, the patient history should reveal exposure to sufficient silica dust to cause this illness. Second, chest imaging (usually chest x-ray) that reveals findings consistent with silicosis. Third, there are no underlying illnesses that are more likely to be causing the abnormalities. Physical examination is usually unremarkable unless there is complicated disease. Also, the examination findings are not specific for silicosis. Pulmonary function testing may reveal airflow limitation, restrictive defects, reduced diffusion capacity, mixed defects, or may be normal (especially without complicated disease). Most cases of silicosis do not require tissue biopsy for diagnosis, but this may be necessary in some cases, primarily to exclude other conditions. Assessment of alveolar crystal burden in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid may aid diagnosis.[19]

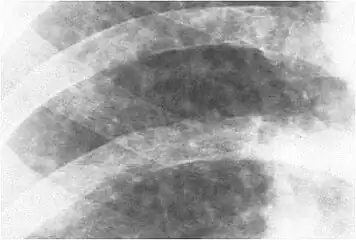

For uncomplicated silicosis, chest x-ray will confirm the presence of small (< 10 mm) nodules in the lungs, especially in the upper lung zones. Using the ILO classification system, these are of profusion 1/0 or greater and shape/size "p", "q", or "r". Lung zone involvement and profusion increases with disease progression. In advanced cases of silicosis, large opacity (> 1 cm) occurs from coalescence of small opacities, particularly in the upper lung zones. With retraction of the lung tissue, there is compensatory emphysema. Enlargement of the hilum is common with chronic and accelerated silicosis. In about 5–10% of cases, the nodes will calcify circumferentially, producing so-called "eggshell" calcification. This finding is not pathognomonic (diagnostic) of silicosis. In some cases, the pulmonary nodules may also become calcified.

A computed tomography or CT scan can also provide a mode detailed analysis of the lungs, and can reveal cavitation due to concomitant mycobacterial infection.

Silicosis- photomicrograph under polarized light shows lung parenchyma with an area of inflammatory infiltrate

Silicosis- photomicrograph under polarized light shows lung parenchyma with an area of inflammatory infiltrate Chest X-ray showing uncomplicated silicosis

Chest X-ray showing uncomplicated silicosis Complicated silicosis

Complicated silicosis Silicosis ILO Classification 2-2 R-R

Silicosis ILO Classification 2-2 R-R.png.webp) Fibrothorax and pleural effusion caused by silicosis

Fibrothorax and pleural effusion caused by silicosis

Classification

Classification of silicosis is made according to the disease's severity (including radiographic pattern), onset, and rapidity of progression.[20] These include:

- Chronic simple silicosis

- Usually resulting from long-term exposure (10 years or more) to relatively low concentrations of silica dust and usually appearing 10–30 years after first exposure.[21] This is the most common type of silicosis. Patients with this type of silicosis, especially early on, may not have obvious signs or symptoms of disease, but abnormalities may be detected by x-ray. Chronic cough and exertional dyspnea (shortness of breath) are common findings. Radiographically, chronic simple silicosis reveals a profusion of small (<10 mm in diameter) opacities, typically rounded, and predominating in the upper lung zones.

- Accelerated silicosis

- Silicosis that develops 5–10 years after first exposure to higher concentrations of silica dust. Symptoms and x-ray findings are similar to chronic simple silicosis, but occur earlier and tend to progress more rapidly. Patients with accelerated silicosis are at greater risk for complicated disease, including progressive massive fibrosis (PMF).

- Complicated silicosis

- Silicosis can become "complicated" by the development of severe scarring (progressive massive fibrosis, or also known as conglomerate silicosis), where the small nodules gradually become confluent, reaching a size of 1 cm or greater. PMF is associated with more severe symptoms and respiratory impairment than simple disease. Silicosis can also be complicated by other lung disease, such as tuberculosis, non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection, and fungal infection, certain autoimmune diseases, and lung cancer. Complicated silicosis is more common with accelerated silicosis than with the chronic variety.

- Acute silicosis

- Silicosis that develops a few weeks to 5 years after exposure to high concentrations of respirable silica dust. This is also known as silicoproteinosis. Symptoms of acute silicosis include more rapid onset of severe disabling shortness of breath, cough, weakness, and weight loss, often leading to death. The x-ray usually reveals a diffuse alveolar filling with air bronchograms, described as a ground-glass appearance, and similar to pneumonia, pulmonary edema, alveolar hemorrhage, and alveolar cell lung cancer.

Prevention

Using the Hierarchy of Controls, there are various methods of preventing exposure to respirable crystalline silica. The best way to prevent silicosis is to avoid worker exposure to dust containing respirable crystalline silica.[22] The next best preventive measure is to control the dust. Water-integrated tools are often used where dust is created during certain tasks. To avoid dust accumulating on clothing and skin, wear a disposable protective suit or seal clothes in an airtight bag and, if possible, shower once returning home. When dust starts accumulating around a workplace, and the use of water-integrated tools is not feasible, an industrial vacuum should be used to contain and transport dust to a safe location for disposal.[23] Dust can also be controlled through personal dry air filtering.[24] The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is a measure of last resort when attempting to control exposure to respirable crystalline silica.

Preventing silicosis may require specific measures. One example is during tunnel construction where purpose-designed cabins are used in addition to air scrubbers to filter the air during construction.[25] Items to be considered when selecting respiratory protection include whether it provides the correct level of protection, if facial fit testing has been provided, if the wearer is absent of facial hair, and how filters will be replaced.[25]

Exposure to siliceous dusts in the ceramics industry is reduced by either processing and using the source materials as aqueous suspension or as damp solids, or by the use of dust control measures such as local exhaust ventilation. These have been mandated by legislation, such as The Pottery (Health and Welfare) Special Regulations 1950.[26][27] The Health and Safety Executive in the UK has produced guidelines Archived 2023-04-25 at the Wayback Machine on controlling exposure to respirable crystalline silica in potteries, and the British Ceramics Federation provide, as a free download, a guidance booklet. Archived 2023-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

Treatment

Silicosis is a permanent disease with no cure.[17] Treatment options currently available focus on alleviating the symptoms and preventing any further progress of the condition. These include:

- Stopping further exposure to airborne silica,[14] silica dust and other lung irritants, including tobacco smoking.

- Cough suppressants.

- Antibiotics for bacterial lung infection.

- Tuberculosis (TB) prophylaxis for those with positive tuberculin skin test or IGRA blood test.

- Prolonged anti-tuberculosis (multi-drug regimen) for those with active TB.

- Chest physiotherapy to help the bronchial drainage of mucus.

- Oxygen administration to treat hypoxemia, if present.

- Bronchodilators to facilitate breathing.

- Lung transplantation to replace the damaged lung tissue is the most effective treatment, but is associated with severe risks of its own from the lung transplant surgery as well as from consequences of long-term immunosuppression (e.g., opportunistic infections).

- For acute silicosis, bronchoalveolar lavage may alleviate symptoms, but does not decrease overall mortality.

- Preliminary work utilising whole lung lavage for patients with artificial stone-associated silicosis has shown significant radiological improvement following whole lung lavage.[28]

Epidemiology

Globally, silicosis resulted in 46,000 deaths in 2013, down from 55,000 deaths in 1990.[6]

Occupational silicosis

Silicosis is the most common occupational lung disease worldwide. It occurs everywhere, but is especially common in developing countries.[29] From 1991 to 1995, China reported more than 24,000 deaths due to silicosis each year.[12] It also affects developed nations. In the United States, it is estimated that between one and two million workers have had occupational exposure to crystalline silica dust and 59,000 of these workers will develop silicosis sometime in the course of their lives.[12][30]

According to CDC data,[31] silicosis in the United States is relatively rare. The incidence of deaths due to silicosis declined by 84% between 1968 and 1999, and only 187 deaths in 1999 had silicosis as the underlying or contributing cause.[32] Additionally, cases of silicosis in Michigan, New Jersey, and Ohio are highly correlated to industry and occupation.[33]

The latest data from The Health and Safety Executive shows that there are typically between 10 and 20 annual Silicosis deaths in recent years, with an average of 12 per year over the last 10 years. In 2019, there were 12 deaths in 10 in 2020, in the UK.[34]

Although silicosis has been a known occupational disease for centuries, the industrialization of mining has led to an increase in silicosis cases . Pneumatic drilling in mines and less commonly, mining using explosives, would raise fine-ultra fine crystalline silica dust (rock dust). In the United States, a 1930 epidemic of silicosis due to the construction of the Hawk's Nest Tunnel near Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, caused the death of at least 400 workers. Other accounts place the mortality figure at well over 1000 workers, primarily African American transient workers from the southern United States.[35] Workers who became ill were fired and left the region, making an exact mortality account difficult.[36] The Hawks Nest Tunnel Disaster is known as "America's worst industrial disaster".[37] The prevalence of silicosis led some men to grow what is called a miner's mustache, in an attempt to intercept as much dust as possible.

Chronic simple silicosis has been reported to occur from environmental exposures to silica in regions with high silica soil content and frequent dust storms.[38]

Also, the mining establishment of Delamar Ghost Town, Nevada, was ruined by a dry-mining process that produced a silicosis-causing dust. After hundreds of deaths from silicosis, the town was nicknamed The Widowmaker. The problem in those days was somewhat resolved with an addition of a nozzle to the drill which sprayed a mist of water, turning dust raised by drilling into mud, but this inhibited mining work.

Because of work-exposure to silica dust, silicosis is an occupational hazard to construction, railroad,[39] demolition, mining, sandblasting, quarry, tunnelling,[40] ceramics and foundry workers, as well as grinders, stone cutters, stone countertops Archived 2022-10-10 at ghostarchive.org (Error: unknown archive URL), refractory brick workers, tombstone workers, workers in the oil and gas industry,[41] pottery workers, fiberglass manufacturing, glass manufacturing, flint knappers and others. Brief or casual exposure to low levels of crystalline silica dust are said to not produce clinically significant lung disease.[42]

In less developed countries where work conditions are poor and respiratory equipment is seldom used, the life expectancy is low (e.g. for silver miners in Potosí, Bolivia, is around 40 years due to silicosis).

Recently, silicosis in Turkish denim sandblasters was detected as a new cause of silicosis due to recurring, poor working conditions.[43]

Silicosis is seen in horses associated with inhalation of dust from certain cristobalite-containing soils in California.

Social realist artist Noel Counihan depicted men who worked in industrial mines in Australia in the 1940s dying of silicosis in his series of six prints, 'The miners' (1947 linocuts).[44]

A recent rise of cases in Australia has been associated with the manufacture and installation of engineered stone bench tops in kitchens and bathrooms.[45][46][47] Engineered stone contains a very high proportion of silica.[48] The Australian Government Department of Health established a National Dust Disease Taskforce in response to the number of reported cases of silicosis in 2018.[49] Workplace health and safety regulations for cutting these bench tops have been tightened in response. The Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union, the major workplace trade union representing construction workers in Australia, has called for a nationwide ban on high-silicon engineered stone by 2024, and stated that it will ban its members from using the material if a governmental ban is not put in place.[50]

Silicosis has also been identified as one of many long-term health outcomes for first responders from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, after having been exposed to dust containing high concentrations of respirable crystalline silica, as well as other metals and toxins.[51]

Desert lung disease

A non-occupational form of silicosis has been described that is caused by long-term exposure to sand dust in desert areas, with cases reported from the Sahara, Libyan desert and the Negev.[52] The disease is caused by deposition of this dust in the lung.[53] Desert lung disease may be related to Al Eskan disease, a lung disorder thought to be caused by exposure to sand dust containing organic antigens, which was first diagnosed after the 1990 Gulf war.[54] The relative importance of the silica particles themselves and the microorganisms that they carry in these health effects remains unclear.[55]

Society and culture

Regulation

In March 2016, OSHA officially mandated that companies must provide certain safety measures for employees who work with or around silica, in order to prevent silicosis, lung cancer, and other silica-related diseases.[56]

Key provisions

One of the main updates to OSHA's silica standard was the reduction of the permissible exposure limit (PEL) for respirable crystalline silica from 250 to 50 micrograms per cubic meter of air, averaged over an 8-hour shift.[57] The updated standard also shifts the focus of controlling silica exposure from the use of PPE (respirators) to the use of engineering controls (such as using water-integrated tools or vacuum systems) and administrative controls (limiting exposure time per shift). Employers are still required to provide respirators when engineering and administrative controls cannot adequately limit exposure. Additional provisions include limiting worker access to high exposure areas, signage requirements in high exposure areas, the development of a written exposure control plan, medical exams to highly exposed workers (optional for exposed employees), and training for workers on silica risks and how to limit exposures. Some recent studies have found workers who grind granite counters and use water controls to eliminate dust are becoming ill from exposure to dust after water has evaporated the next day.[58] The standard also provides requirements for cleaning up the slurry left behind when water-integrated tools are used as an engineering control.

The medical exams include a discussion with a physician or licensed health care provider (PLHCP) of prior respiratory health, chest X-ray, pulmonary function test, latent tuberculosis infection, and any other tests deemed necessary by the PLHCP. These medical exams are to occur within 30 days of the initial assignment that includes silica exposure and must be made available for renewal at least every three years unless the PLHCP deems otherwise.

As part of the updated standard, OSHA created a table of specific engineering and administrative control methods to reduce silica exposure when using specific tools in 18 different applications that are known to create an exposure to silica from stationary masonry saws to using handheld grinders.[57]

An additional provision exists for small business who are provided flexibility.[59]

Compliance schedule

Both standards contained in the final rule took effect on June 23, 2016, after which industries had one to five years to comply with most requirements, based on the following schedule:

- Construction – June 23, 2017, one year after the effective date.

- General Industry and Maritime – June 23, 2018, two years after the effective date.

- Hydraulic Fracturing – June 23, 2018, two years after the effective date for all provisions except Engineering Controls, which have a compliance date of June 23, 2021.[59]

See also

- Pneumoconiosis – Class of interstitial lung diseases

- Asbestosis – Pneumoconiosis caused by inhalation and retention of asbestos fibers

- Health effects arising from the September 11 attacks – Health issues and effects during and after the September 11 attacks

- Hawks Nest Tunnel disaster – Tunnel in West Virginia where hundreds of workers contracted silicosis

- Dust pneumonia

- Frances Perkins

References

- ↑ Jane A. Plant; Nick Voulvoulis; K. Vala Ragnarsdottir (13 March 2012). Pollutants, Human Health and the Environment: A Risk Based Approach. John Wiley & Sons. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-470-74261-7. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ↑ "Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ↑ Derived from Gr. πνεῦμα pneúm|a (lung) + buffer vowel -o- + κόνις kóni|s (dust) + Eng. scient. suff. -osis (like in asbest"osis" and silic"osis", see ref. 10).

- ↑ "Prevention of Silicosis Deaths". July 22, 2015. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- 1 2 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ United States Bureau of Mines, "Bulletin: Volumes 476–478", U.S. G.P.O., (1995), p 63.

- ↑ Rosen G: The History of Miners' Diseases: A Medical and Social Interpretation. New York, Schuman, 1943, pp.459–476.

- ↑ 'The Successful Prevention Of Silicosis Among China Biscuit Workers In The North Staffordshire Potteries.' A. Meiklejohn. British Journal Of Industrial Medicine, October 1963; 20(4): 255–263

- 1 2 "Diseases associated with exposure to silica and nonfibrous silicate minerals. Silicosis and Silicate Disease Committee". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 112 (7): 673–720. July 1988. PMID 2838005.

- ↑ Stop Silicosis, archived from the original on 2022-04-21, retrieved 2022-04-21

- 1 2 3 "Silicosis Fact Sheet". World Health Organization. May 2000. Archived from the original on 2007-05-10. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ↑ Cowie RL (November 1994). "The epidemiology of tuberculosis in gold miners with silicosis". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 150 (5 Pt 1): 1460–2. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952577. PMID 7952577.

- 1 2 Mouna, Mlika (February 9, 2022). "Silicosis". StatPearls. PMID 30726026. Archived from the original on March 2, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ↑ Pelucchi C, Pira E, Piolatto G, Coggiola M, Carta P, La Vecchia C (July 2006). "Occupational silica exposure and lung cancer risk: a review of epidemiological studies 1996–2005". Ann. Oncol. 17 (7): 1039–50. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdj125. PMID 16403810.

- ↑ Cassel SL, Eisenbarth SC, Iyer SS, et al. (June 2008). "The Nalp3 inflammasome is essential for the development of silicosis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (26): 9035–40. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9035C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803933105. PMC 2449360. PMID 18577586.

- 1 2 Wagner, GR (May 1997). "Asbestosis and silicosis". Lancet. 349 (9061): 1311–1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07336-9. PMID 9142077. S2CID 26302715. Archived from the original on 2020-06-05. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ↑ Crystalline Silica Primer, US Dept of the Interior and US Bureau of Mines, 1992.

- ↑ Apte, Simon H.; Tan, Maxine E.; Lutzky, Viviana P.; De Silva, Tharushi A.; Fiene, Andreas; Hundloe, Justin; Deller, David; Sullivan, Clair; Bell, Peter T.; Chambers, Daniel C. (2022-02-17). "Alveolar crystal burden in stone workers with artificial stone silicosis". Respirology. 27 (6): 437–446. doi:10.1111/resp.14229. ISSN 1440-1843. PMC 9307012. PMID 35176815. S2CID 246943673.

- ↑ NIOSH Hazard Review. Health Effects of Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica. DHHS 2002-129. pp. 23.

- ↑ Weisman DN and Banks DE. Silicosis. In: Interstitial Lung Disease. 4th ed. London: BC Decker Inc. 2003, pp391.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2007). "Elimination of Silicosis" (PDF). GOHNET NEWSLETTER. No. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "Guide to Training Your Staff for OSHA Compliance | Industrial Vacuum". www.industrialvacuum.com. 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 2018-10-24. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- ↑ CPWR-The Center for Construction Research and Training. "Work Safely with Silica: methods to control silica exposure". Archived from the original on 2012-12-20.

- 1 2 ATS (7 January 2019). "NSW Air Quality Working Group". Australian Tunnelling Society. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2023-07-24. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ 'Whitewares: Production, Testing And Quality Control." W.Ryan & C.Radford. Pergamon Press. 1987

- ↑ Chambers, Daniel C.; Apte, Simon H.; Deller, David; Masel, Philip J.; Jones, Catherine M.; Newbigin, Katrina; Matula, Michael; Rapchuk, Ivan L. (May 2021). "Radiological outcomes of whole lung lavage for artificial stone-associated silicosis". Respirology. 26 (5): 501–503. doi:10.1111/resp.14018. ISSN 1440-1843. PMID 33626187. S2CID 232047922. Archived from the original on 2023-04-17. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ↑ Steenland K, Goldsmith DF (November 1995). "Silica exposure and autoimmune diseases". Am. J. Ind. Med. 28 (5): 603–8. doi:10.1002/ajim.4700280505. PMID 8561170.

- ↑ "Safety and Health Topics Silica, Crystalline". Occupational Safety and Health Administration. March 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-05-18. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ↑ "Ch. 2: Fatal and Nonfatal Injuries, and Selected Illnesses: Respiratory Diseases: Pneumoconioses: Silicosis". Worker Health Chartbook 2004. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). 2004. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2004146. 2004-146. Archived from the original on 2017-11-23.

- ↑ NIOSH & 2004-146, Fig2-192

- ↑ NIOSH & 2004-146, Fig2-190

- ↑ "Silicosis and coal workers' pneumoconiosis statistics in Great Britain, 2021" (PDF). hse.gov.uk/. December 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-05-18. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ↑ "The Hawks Nest Tunnel," Patricia Spangler, 2008

- ↑ Keenan, Steve (2008-04-02). "Book explores Hawks Nest tunnel history » Local News » The Fayette Tribune, Oak Hill, W.Va". Fayettetribune.com. Archived from the original on 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2012-02-16.

- ↑ "The Hawk’s Nest Incident: America’s Worst Industrial Disaster," Dr. Martin Cherniack 1986

- ↑ Norboo T, Angchuk PT, Yahya M, et al. (May 1991). "Silicosis in a Himalayan village population: role of environmental dust". Thorax. 46 (5): 341–3. doi:10.1136/thx.46.5.341. PMC 463131. PMID 2068689.

- ↑ "Los Angeles Silica Exposure Lawyer". Rose, Klein & Marias LLP. Archived from the original on 2022-05-17. Retrieved 2022-06-01.

- ↑ Cole, Kate (7 January 2020). "Investigating best practice to prevent illness and disease in tunnel construction workers". Winston Churchill Trust Australia. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ↑ "NIOSHTIC-2 Publications Search - 20040975 - OSHA/NIOSH hazard alert: worker exposure to silica during hydraulic fracturing". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-03-17. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ "Adverse effects of crystalline silica exposure. American Thoracic Society Committee of the Scientific Assembly on Environmental and Occupational Health". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 155 (2): 761–8. February 1997. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032226. PMID 9032226.

- ↑ Denim sandblasters contract fatal silicosis in illegal workshops Archived 2009-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Art Gallery of NSW: Noel Couniham Collection Archived 2014-09-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Atkin, Michael (7 January 2020). "The biggest lung disease crisis since asbestos: Our love of stone kitchen benchtops is killing workers". ABC News. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ↑ Atkin, Michael (7 January 2020). "Silicosis-causing silica significantly 'more potent' than asbestos". ABC News. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ↑ Cole, Kate (7 January 2020). "Silicosis is not the new Asbestosis". ABC Radio National. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ↑ "Preventing exposure to silica from engineered stone benchtops". Worksafe Tasmania. Government of Tasmania. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ↑ DoH (2019-11-21). "The Department of Health National Dust Disease Taskforce". Department of Health. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ↑ Lloyd, Mary (22 November 2022). "Risky, silicosis-causing stone product must be banned, construction union tells government". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ↑ Jiehui, Li (March 7, 2019). "Pulmonary Fibrosis among World Trade Center Responders: Results from the WTC Health Registry Cohort". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16 (5): 825. doi:10.3390/ijerph16050825. PMC 6427469. PMID 30866415.

- ↑ Hawass ND (September 1987). "An association between 'desert lung' and cataract—a new syndrome". Br J Ophthalmol. 71 (9): 694–7. doi:10.1136/bjo.71.9.694. PMC 1041277. PMID 3663563.

- ↑ Nouh MS (1989). "Is the desert lung syndrome (nonoccupational dust pneumoconiosis) a variant of pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis? Report of 4 cases with review of the literature". Respiration. 55 (2): 122–6. doi:10.1159/000195715. PMID 2549601.

- ↑ Korényi-Both AL, Korényi-Both AL, Molnár AC, Fidelus-Gort R (September 1992). "Al Eskan disease: Desert Storm pneumonitis". Mil Med. 157 (9): 452–62. doi:10.1093/milmed/157.9.452. PMID 1333577.

- ↑ Griffin DW (July 2007). "Atmospheric movement of microorganisms in clouds of desert dust and implications for human health". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20 (3): 459–77, table of contents. doi:10.1128/CMR.00039-06. PMC 1932751. PMID 17630335.

- ↑ "OSHA publishes final rule on silica". Archived from the original on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- 1 2 "1926.1153 Respirable Crystalline Silica". osha.gov. March 25, 2016. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ↑ Greenfieldboyce, Nell (2019-10-02). "Workers Are Falling Ill, Even Dying, After Making Kitchen Countertops". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 2019-11-27. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- 1 2 "OSHA's Final Rule to Protect Workers from Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica". www.osha.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-08-20. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

External links

- Crystalline silica Archived 2023-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, US.

- Preventing Silicosis and Deaths in Construction workers Archived 2023-04-17 at the Wayback Machine, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, US.

- OSHA’s Respirable Crystalline Silica Standard for Construction Archived 2023-05-19 at the Wayback Machine, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, US.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |