Saint Louis encephalitis

| Saint Louis encephalitis | |

|---|---|

_virus_EM_PHIL_1871_lores.JPG.webp) | |

| Electron micrograph of "Saint Louis encephalitis virus" seen in a mosquito salivary gland | |

| Symptoms | Mild illness, including fever and headache. (if severe) High fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, occasional convulsions and spastic paralysis |

| Causes | Saint Louis encephalitis virus |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test, spinal fluid test,clinical presentation |

| Differential diagnosis | Japanese encephalitis,Herpes simplex encephalitis, Eastern equine encephalitis, Zika virus, Ehrlichiosis |

| Prevention | No vaccine |

| Treatment | Supportive care |

| Saint Louis encephalitis virus | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Flasuviricetes |

| Order: | Amarillovirales |

| Family: | Flaviviridae |

| Genus: | Flavivirus |

| Species: | Saint Louis encephalitis virus |

| Synonyms | |

Saint Louis encephalitis is a disease caused by the mosquito-borne Saint Louis encephalitis virus.[3]

Saint Louis encephalitis virus is related to Japanese encephalitis virus and is a member of the family Flaviviridae.[3] This disease mainly affects the United States, including Hawaii.[4]

Occasional cases have been reported from Canada, Mexico and the Caribbean, including the Greater Antilles, Trinidad and Tobago, and Jamaica.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The majority of infections result in mild illness, including fever and headache. When infection is more severe the person may experience headache, high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, occasional convulsions and spastic paralysis. Elderly people are more likely to have a fatal infection.[5][6][7]

Cause

The cause of this condition is Saint Louis encephalitis virus, which is a Flavivirus, a single-stranded RNA virus .[6]Flaviviruses have positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genomes which are non-segmented and around 10–11 kbp in length.[8] In general, the genome encodes three structural proteins (Capsid, prM, and Envelope) and seven non-structural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5).[9] The genomic RNA is modified at the 5′ end of positive-strand genomic RNA with a cap-1 structure (me7-GpppA-me2).[10]

Transmission

Mosquitoes, primarily from the genus Culex, become infected by feeding on birds infected with the Saint Louis encephalitis virus. The most common vector of this disease within the genus Culex is Culex pipiens, also known as the common house mosquito.[11]

Infected mosquitoes then transmit the Saint Louis encephalitis virus to humans and animals during the feeding process, the Saint Louis encephalitis virus grows both in the infected mosquito and the infected bird. [12][13]

Only infected mosquitoes can transmit Saint Louis encephalitis virus. Once a human has been infected with the virus it is not transmissible from that individual to other humans,[12][13] though very rarely it has occurred via blood transfusion.

Mechanism

The pathophysiology of Saint Louis encephalitis occurs via replication in the local lymph nodes (near mosquito bite).[6]

In terms of family Flaviviridae replication, this happens via creating an antigenome as a template for genome RNA to be produced. Replication complexes are isolated in membranous structures inside the endoplasmic reticulum. Serine protease, an RNA helicase and an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is among the enzymes (replication). As for virion assembly, this happens by budding through intracellular membranes. [14]

Diagnosis

In terms of the diagnosis of Saint Louis encephalitis the following is done when an individual is suspected of infection:[15]

- History of having traveled to where SLE virus exists

- Blood test

- Spinal fluid test

- Clinical presentation

.jpg.webp) Lumbar puncture in a sitting position. The reddish-brown swirls on individuals back are tincture of iodine (an antiseptic).

Lumbar puncture in a sitting position. The reddish-brown swirls on individuals back are tincture of iodine (an antiseptic). A venipuncture performed using a vacutainer

A venipuncture performed using a vacutainer

Differential diagnosis

The DDx of this infection is as follows:[6]

- Japanese encephalitis

- Herpes simplex encephalitis

- Eastern equine encephalitis

- Zika virus

- Ehrlichiosis

- Enterovirus meningitis

- Mycoplasma meningitis

- Typhoid fever

- Dengue fever

- Malaria

- Brain abscess

- Powassan Virus encephalitis

- West Nile virus encephalitis

Treatment

The management of this condition is limited to supportive care with intravenous fluids.[6]

There are no vaccines or any other treatments specifically for Saint Louis encephalitis virus, although one study showed that early use of interferon alfa-2b may decrease the severity of complications.[16]

Epidemiology

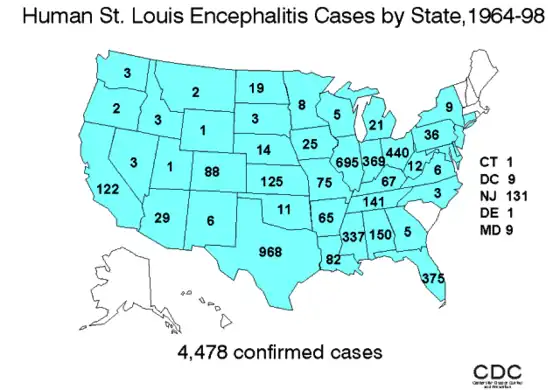

In the United States an average of more than 100 cases of Saint Louis encephalitis are recorded annually. In temperate areas of the United States, Saint Louis encephalitis cases occur primarily in the late summer. In the southern United States where the climate is milder Saint Louis encephalitis can occur year-round.[17][18]

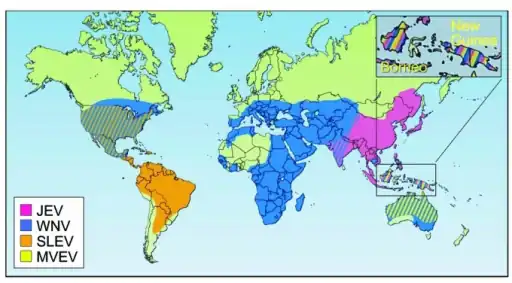

Geographic distribution of four members of the JE serological group: JEV,WNV,MVEVV, and St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV)

Geographic distribution of four members of the JE serological group: JEV,WNV,MVEVV, and St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) Human incidence of Saint Louis encephalitis in the United States, 1964–1998.

Human incidence of Saint Louis encephalitis in the United States, 1964–1998.

History

The name of the virus goes back to 1933 when within five weeks in autumn an encephalitis epidemic of explosive proportions broke out in the vicinity of St. Louis, Missouri, and the neighboring St. Louis County.[19][20]

Over 1,000 cases were reported to the local health departments and the newly constituted National Institutes of Health of the United States was appealed to for epidemiological and investigative expertise.[21]

The previously unknown virus that caused the epidemic was isolated by the NIH team first in monkeys and then in white mice.[22]

Evolution

Five evolutionary genetic studies of SLE virus have been published of which four[23][24][25][26] focused on phylogeny, genetic variation, and recombination dynamics by sequencing the envelope protein gene and parts of other genes.A recent evolutionary study[27] based on 23 new full open reading frame sequences (near-complete genomes) found that the North American strains belonged to a single clade. Strains were isolated at different points in time (from 1933 to 2001) which allowed for the estimation of divergence times of SLE virus clades and the overall evolutionary rate. Furthermore, this study found an increase in the effective population size of the SLE virus around the end of the 19th century that corresponds to the split of the latest North American clade, suggesting a northwards colonization of SLE virus in the Americas, and a split from the ancestral South American strains around 1892.[28] Scans for natural selection showed that most codons of the SLE virus ORF were evolving neutrally or under negative selection. Positive selection was statistically detected only at one single codon coding for amino acids belonging to the hypothesized N-linked glycosylation site of the envelope protein. Nevertheless, the latter can be due to selection in vitro (laboratory) rather than in vivo (host). In an independent study[26] 14 out of 106 examined envelope gene sequences were found not to contain a specific codon at position 156 coding for this glycosylation site (Ser→Phe/Tyr).

Another study estimated the evolutionary rate to be 4.1 × 10−4 substitutions/site/year (95% confidence internal 2.5-5.7 × 10−4 substitutions/site/year),[29] the virus seems to have evolved in northern Mexico and then spread northwards with migrating birds.

References

- ↑ Siddell, Stuart (April 2017). "Change the names of 43 virus species to accord with ICVCN Code, Section 3-II, Rule 3.13 regarding the use of ligatures, diacritical marks, punctuation marks (excluding hyphens), subscripts, superscripts, oblique bars and non-Latin letters in taxon names" (ZIP). International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ↑ ICTV 5th Report Francki, R. I. B., Fauquet, C. M., Knudson, D. L. & Brown, F. (eds)(1991). Classification and nomenclature of viruses. Fifthreport of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archives of Virology Supplementum 2, p226 https://ictv.global/ictv/proposals/ICTV%205th%20Report.pdf Archived 2023-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Bleck, Thomas P.; Damon, Inger K. (2020). "359. Arboviruses affecting the central nervous system". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 2233. ISBN 978-0-323-53266-2. Archived from the original on 2023-09-10. Retrieved 2023-09-09.

- 1 2 Mavian, Carla; Dulcey, Melissa; Munoz, Olga; Salemi, Marco; Vittor, Amy; Capua, Ilaria (25 December 2018). "Islands as Hotspots for Emerging Mosquito-Borne Viruses: A One-Health Perspective". Viruses. 11 (1): 11. doi:10.3390/v11010011. PMC 6356932. PMID 30585228.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions | St. Louis Encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 3 March 2021. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Simon, Leslie V.; Kong, Erwin L.; Graham, Charles (2023). "St. Louis Encephalitis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ↑ "Encephalitis". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ↑ "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Rice, C.; Lenches, E.; Eddy, S.; Shin, S.; Sheets, R.; Strauss, J. (23 August 1985). "Nucleotide sequence of yellow fever virus: implications for flavivirus gene expression and evolution". Science. 229 (4715): 726–33. Bibcode:1985Sci...229..726R. doi:10.1126/science.4023707. PMID 4023707. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ Henderson, Brittney R.; Saeedi, Bejan J.; Campagnola, Grace; Geiss, Brian J. (12 October 2011). "Analysis of RNA Binding by the Dengue Virus NS5 RNA Capping Enzyme". PLoS ONE. 6 (10): e25795. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025795. ISSN 1932-6203. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ↑ "Saint Louis Encephalitis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 20, 2009. Archived from the original on June 18, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- 1 2 "Transmission | St. Louis Encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 3 March 2021. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- 1 2 Oyer, Ryan J.; David Beckham, J.; Tyler, Kenneth L. (1 January 2014). "Chapter 20 - West Nile and St. Louis encephalitis viruses". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Elsevier. pp. 433–447. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ↑ Simmonds, Peter; Becher, Paul; Bukh, Jens; Gould, Ernest A; Meyers, Gregor; Monath, Tom; Muerhoff, Scott; Pletnev, Alexander; Rico-Hesse, Rebecca; Smith, Donald B; Stapleton, Jack T (2017). "ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Flaviviridae". The Journal of General Virology. 98 (1): 2–3. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000672. ISSN 0022-1317. Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ↑ "Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment | St. Louis Encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 14 October 2022. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ↑ Rahal JJ, Anderson J, Rosenberg C, Reagan T, Thompson LL (2004). "Effect of interferon-alpha2b therapy on St. Louis viral meningoencephalitis: clinical and laboratory results of a pilot study". J. Infect. Dis. 190 (6): 1084–7. doi:10.1086/423325. PMID 15319857.

- ↑ Reisen, William K. (2003). "Epidemiology of St. Louis encephalitis virus". Advances in Virus Research. 61: 139–183. doi:10.1016/s0065-3527(03)61004-3. ISSN 0065-3527. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ↑ Curren, Emily J.; Lindsey, Nicole P.; Fischer, Marc; Hills, Susan L. (October 2018). "St. Louis Encephalitis Virus Disease in the United States, 2003-2017". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 99 (4): 1074–1079. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.18-0420. ISSN 1476-1645. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ↑ "Encephalitis in St. Louis". American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 23 (10): 1058–60. October 1933. doi:10.2105/ajph.23.10.1058. PMC 1558319. PMID 18013846.

- ↑ Washington Post Magazine, October 8, 1933

- ↑ Bredeck JF (November 1933). "The Story of the Epidemic of Encephalitis in St. Louis". American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 23 (11): 1135–40. doi:10.2105/AJPH.23.11.1135. PMC 1558406. PMID 18013860.

- ↑ Edward A. Beeman: Charles Armstrong, M.D.: A Biography; 2007; p. 305; also online here (PDF) Archived 2017-04-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kramer LD, Presser SB, Hardy JL, Jackson AO (1997). "Genotypic and phenotypic variation of selected Saint Louis encephalitis viral strains isolated in California". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 57 (2): 222–9. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.222. PMID 9288820.

- ↑ Kramer LD, Chandler LJ (2001). "Phylogenetic analysis of the envelope gene of St. Louis encephalitis virus". Arch. Virol. 146 (12): 2341–55. doi:10.1007/s007050170007. PMID 11811684. S2CID 24755534.

- ↑ Twiddy SS, Holmes EC (2003). "The extent of homologous recombination in members of the genus Flavivirus". J. Gen. Virol. 84 (Pt 2): 429–40. doi:10.1099/vir.0.18660-0. PMID 12560576.

- 1 2 May FJ, Li L, Zhang S, Guzman H, Beasley DW, Tesh RB, Higgs S, Raj P, Bueno R, Randle Y, Chandler L, Barrett AD (2008). "Genetic variation of St. Louis encephalitis virus". J. Gen. Virol. 89 (Pt 8): 1901–10. doi:10.1099/vir.0.2008/000190-0. PMC 2696384. PMID 18632961.

- ↑ Baillie GJ, Kolokotronis SO, Waltari E, Maffei JG, Kramer LD, Perkins SL (2008). "Phylogenetic and evolutionary analyses of St. Louis encephalitis virus genomes". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 47 (2): 717–28. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.02.015. PMID 18374605.

- ↑ "Solving The Mystery Of St. Louis Encephalitis". American Museum of Natural History. 30 July 2008. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ↑ Auguste AJ, Pybus OG, Carrington CV (2009). "Evolution and dispersal of St. Louis encephalitis virus in the Americas". Infect. Genet. Evol. 9 (4): 709–15. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.07.006. PMID 18708161.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Saint Louis encephalitis Archived 2023-01-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- St. Louis Encephalitis at eMedicine

- The Encephalitis Society - A Global resource on Encephalitis Archived 2021-03-23 at the Wayback Machine

- "St. Louis encephalitis virus". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 11080. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2023-01-30.