Tick-borne encephalitis vaccine

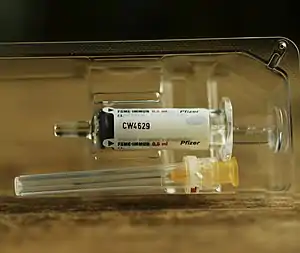

FSME-Immun (European TBE vaccine) | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Tick-borne encephalitis virus |

| Type | Inactivated |

| Names | |

| Trade names | Encepur N, FSME-Immun CC, others |

Tick-borne encephalitis vaccine is a vaccine used to prevent tick-borne encephalitis (TBE).[1] The disease is most common in Central and Eastern Europe, and Northern Asia.[1] More than 87% of people who receive the vaccine develop immunity.[2] It is not useful following the bite of an infected tick.[1] It is given by injection into a muscle.[1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends immunizing all people in areas where the disease is common.[1] Otherwise the vaccine is just recommended for those who are at high risk.[1] Three doses are recommended followed by additional doses every three to five years.[1] The vaccines can be used in people more than one or three years of age depending on the formulation.[1] The vaccine appears to be safe during pregnancy.[1]

Serious side effects are rare.[1] Restlessness is an uncommon side effect in children.[3] Minor side effects may include fever, and redness and pain at the site of injection.[1] Older formulations were more commonly associated with side effects.[1] All tick-borne encephalitis vaccines are inactivated whole virus alum-adjuvanted vaccines.[4]

The first vaccine against TBE was developed in 1937.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5] Per dose it costs £30 in the United Kingdom as of 2021.[3] The vaccine is not available in the United States.[6] Two types are available in Russia and two in Europe.[4]

Medical uses

The efficacy of these vaccines has been well documented.[1] They have also been shown to protect mice from a lethal challenge with several TBE-virus isolates obtained over a period of more than 30 years from all over Europe and the Asian part of the former Soviet Union. In addition, it has been demonstrated that antibodies induced by vaccination of human volunteers neutralized all tested isolates.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

The vaccine appears to be safe during pregnancy,[1] but because of insufficient data the vaccine is only recommended during pregnancy and breastfeeding when it is considered urgent to achieve protection against TBE infection and after careful consideration of risks versus benefits.[7]

Schedule

Two to three doses are recommended depending on the formulation. [1] Typically one to three months should occur between the first doses followed by five to twelve months before the final dose, preferably prior to the tick season.[4] Additional doses are then recommended every three to five years.[1] Both European vaccines can be given over a shorter duration as an accelerated course.[4]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is not established.[8]

History

The first vaccine against TBE was prepared in 1937 in the brains of mice. Some 20 years later TBE vaccines derived from cell cultures (chicken embryo fibroblast cells) were developed and used for active immunization in humans in the former Soviet Union. Later, a purified, inactivated virus vaccine was developed which proved to be more immunogenic than previous TBE vaccines.

The first European TBE vaccine became available in 1976.[4]

Trade names

Trade names of the vaccines include Encepur N[9] and FSME-Immun CC.[10]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 World Health Organization (June 2011). "Vaccines against tick-borne encephalitis : WHO position paper". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 86 (24): 241–56. hdl:10665/241769. PMID 21661276. Lay summary (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help) - ↑ Demicheli V, Debalini MG, Rivetti A (2009). "Vaccines for preventing tick-borne encephalitis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000977. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000977.pub2. PMC 6532705. PMID 19160184.

- 1 2 "14. Vaccines". British National Formulary (BNF) (82 ed.). London: BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2021 – March 2022. p. 1393. ISBN 978-0-85711-413-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Kollaritsch, Herwig; Heininger, Ulrich (2021). "16. Tick-borne encephalitis vaccines". In Vesikari, Timo; Damme, Pierre Van (eds.). Pediatric Vaccines and Vaccinations: A European Textbook (Second ed.). Switzerland: Springer. pp. 159–170. ISBN 978-3-030-77172-0. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "3: Infectious Diseases Related to Travel". CDC Health Information for International Travel 2016. Oxford University Press. June 1, 2015. ISBN 978-0199379156. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016.

- ↑ Gabutti, Giovanni; Conforti, Giorgio; Tomasi, Alberto; Kuhdari, Parvanè; Castiglia, Paolo; Prato, Rosa; Memmini, Silvia; Azzari, Chiara; Rosati, Giovanni Vitali; Bonanni, Paolo (2016). "Why, when and for what diseases pregnant and new mothers "should" be vaccinated". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 13 (2): 283–290. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1264773. ISSN 2164-5515. PMC 5328236. PMID 27929742.

- ↑ "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ↑ "Encepur N". compendium.ch. 2016-04-28. Archived from the original on 2019-12-14. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- ↑ "FSME-Immun CC". compendium.ch. 2017-08-11. Archived from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Tick-borne Encephalitis Vaccine". World Health Organization (WHO). 12 October 2011. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2019.