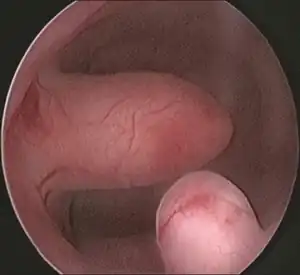

Endometrial polyp

| Endometrial polyp | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Uterine polyp | |

| |

| Endometrial polyp at hysteroscopy | |

| Specialty | Gynaecology |

| Symptoms | None, abnormal vaginal bleeding, infertility[1] |

| Usual onset | Around menopause[1] |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Risk factors | Tamoxifen[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Transvaginal ultrasonography, color doppler, hysteroscopy, histology[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Uterine fibroid[3] |

| Treatment | Surgery (Polypectomy)[2] |

| Prognosis | 11% to 30% hyperplasia, 0.5% to 3% cancer, some resolve without treatment[1][3] |

| Frequency | Common[4] |

An endometrial polyp, also known as a uterine polyp is a growth attached to the inside of the uterus.[1] There may be no symptoms, or it can result in abnormal vaginal bleeding and difficulty becoming pregnant.[1] They can vary in size from very small to large enough to fill the entire uterine cavity.[2] There may be one or several, and typically have a stalk which may have a narrow or wide base.[1] If the stalk is long enough, it may protrude into the vagina.[3]

The cause is not known.[1] It is an overgrowth of endocrine glands, also containing stroma and blood vessels and typically situated at the inner uterus.[3] Larger, multiple endometrial polyps may occur in those taking tamoxifen.[1] Diagnosis is by transvaginal ultrasonography, the accuracy of which is improved with color doppler.[2] Confirmation is by microscopic examination of the polyp once cut out during hysteroscopy.[2]

Some resolve without treatment.[3] The majority are noncancerous, however 11% to 30% have or develop hyperplasia, and 0.5% to 3% become cancer.[1] Endometrial polyps are common.[4] Most occur in the 40s and 50s, around menopause.[1]

Signs and symptoms

They often cause no symptoms.[1] Where they occur, symptoms include irregular menstrual bleeding, bleeding between menstrual periods, excessively heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia), and vaginal bleeding after menopause.[5][6] Bleeding from the blood vessels of the polyp contributes to an increase of blood loss during menstruation and blood "spotting" between menstrual periods, or after menopause.[7] If the polyp protrudes through the cervix into the vagina, pain (dysmenorrhea) may result.[8]

Cause

No definitive cause of endometrial polyps is known, but they appear to be affected by hormone levels and grow in response to circulating estrogen.[3] Risk factors include obesity, high blood pressure and a history of cervical polyps.[5] Taking tamoxifen or hormone replacement therapy can also increase the risk of uterine polyps.[5][9] The use of an intrauterine system containing levonorgestrel in women taking tamoxifen may reduce the incidence of polyps.[10] Pedunculated polyps are more common than sessile ones.[11]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is by transvaginal ultrasonography and accuracy is improved with color doppler.[2] Other tests include hysteroscopy.[2]

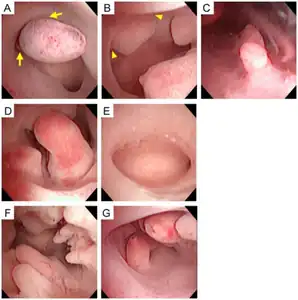

.png.webp) Diagram showing location of polyps

Diagram showing location of polyps (A) Pedunculated. (B) Sessile. (C) Intracavitary bleeding. (D, E) No after polypectomy. (F, G) Recurrence after polypectomy.

(A) Pedunculated. (B) Sessile. (C) Intracavitary bleeding. (D, E) No after polypectomy. (F, G) Recurrence after polypectomy. Endometrial polyp, viewed by sonography

Endometrial polyp, viewed by sonography

Pathology

Endometrial polyps can be solitary or occur with others.[12] They are round or oval and measure between a few millimeters and several centimeters in diameter.[7][12] They are usually the same red/brown color of the surrounding endometrium although large ones can appear to be a darker red.[7] The polyps consist of dense, fibrous tissue (stroma), blood vessels and glandlike spaces lined with endometrial epithelium.[7] If they are pedunculated, they are attached by a thin stalk (pedicle). If they are sessile, they are connected by a flat base to the uterine wall.[12] Pedunculated polyps are more common than sessile ones.[11]

Micrograph of an endometrial polyp. H&E stain

Micrograph of an endometrial polyp. H&E stain Myometrium (smooth muscle cells) versus endometrial stroma (more cellular) versus endometrial polyp stroma (more collagenous). H&E stain

Myometrium (smooth muscle cells) versus endometrial stroma (more cellular) versus endometrial polyp stroma (more collagenous). H&E stain

Treatment

Polyps can be surgically removed using curettage with or without hysteroscopy.[13] When curettage is performed without hysteroscopy, polyps may be missed. To reduce this risk, the uterus can be first explored using grasping forceps at the beginning of the curettage procedure.[7] Hysteroscopy involves visualising the endometrium (inner lining of the uterus) and polyp with a camera inserted through the cervix. Large polyps can be cut into sections before each section is removed.[7] The presence of cancerous cells may suggest a hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus).[5] A hysterectomy is usually not considered when cancer is not present.[7] In either procedure, general anesthetic is typically supplied.[14]

The effects of polyp removal on fertility is not clear.[15]

Prognosis

Some resolve without treatment.[2] The majority are noncancerous, but a few may have hyperplasia or develop hyperplasia and a minority may have or develop carcinoma.[1] Hence, all require histopathological analysis.[2]

Polyps can increase the risk of miscarriage in women undergoing IVF treatment.[5] If they develop near the fallopian tubes, they may lead to difficulty in becoming pregnant.[5] Although treatments such as hysteroscopy usually cure the polyp concerned, recurrence of endometrial polyps is frequent.[7]

Epidemiology

Endometrial polyps are common.[4] Most are harmless; however 11% to 30% have or develop hyperplasia, and 0.5% to 3% turn into a cancer.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "6. Tumours of the uterine corpus: Endometrial polyp". Female genital tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 4 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. p. 268. ISBN 978-92-832-4504-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Vitale, Salvatore Giovanni; Haimovich, Sergio; Laganà, Antonio Simone; Alonso, Luis; Di Spiezio Sardo, Attilio; Carugno, Jose (May 2021). "Endometrial polyps. An evidence-based diagnosis and management guide". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 260: 70–77. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.03.017. ISSN 1872-7654. PMID 33756339. Archived from the original on 2022-08-02. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nijkang, NP; Anderson, L; Markham, R; Manconi, F (2019). "Endometrial polyps: Pathogenesis, sequelae and treatment". SAGE open medicine. 7: 2050312119848247. doi:10.1177/2050312119848247. PMID 31105939. Archived from the original on 2022-05-24. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- 1 2 3 Raz, Nili; Feinmesser, Larissa; Moore, Omer; Haimovich, Sergio (October 2021). "Endometrial polyps: diagnosis and treatment options - a review of literature". Minimally invasive therapy & allied technologies: MITAT: official journal of the Society for Minimally Invasive Therapy. 30 (5): 278–287. doi:10.1080/13645706.2021.1948867. ISSN 1365-2931. PMID 34355659. Archived from the original on 2022-08-02. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Uterine polyps". MayoClinic.com. 2006-04-27. Archived from the original on 2012-07-28. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ↑ "Endometrial Polyp". GPnotebook. Archived from the original on 2008-01-07. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 DeCherney, Alan H.; Lauren Nathan (2003). Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 703. ISBN 0-8385-1401-4.

- ↑ Dysmenorrhea: Menstrual abnormalities at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ↑ Edmonds, D. Keith; Sir John Dewhurst (2006). Dewhurst's Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Blackwell Publishing. p. 637. ISBN 1-4051-5667-8. Archived from the original on 2020-06-15. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ↑ Chan SS, Tam WH, Yeo W, et al. (2007). "A randomised controlled trial of prophylactic levonorgestrel intrauterine system in tamoxifen-treated women". BJOG. 114 (12): 1510–5. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01545.x. PMID 17995495. S2CID 21145823.

- 1 2 Sternberg, Stephen S.; Stacey E. Mills; Darryl Carter (2004). Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 2460. ISBN 0-7817-4051-7. Archived from the original on 2020-06-15. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- 1 2 3 Bajo Arenas, José M.; Asim Kurjak (2005). Donald School Textbook Of Transvaginal Sonography. Taylor & Francis. p. 502. ISBN 1-84214-331-X. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ↑ "Uterine bleeding – Signs and Symptoms". UCSF Medical Center. 2007-05-08. Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- ↑ Macnair, Trisha. "Ask the doctor – Uterine polyps". BBC Health. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- ↑ Jayaprakasan, K; Polanski, L; Sahu, B; Thornton, JG; Raine-Fenning, N (Aug 30, 2014). "Surgical intervention versus expectant management for endometrial polyps in subfertile women" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD009592. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009592.pub2. PMC 6544777. PMID 25172985. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

External links

| Classification |

|---|