Abortion in the United Kingdom

Abortion is available legally throughout the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

In Northern Ireland abortion does not constitute a criminal offence after sections of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 were repealed in October 2019. The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020 commenced on 31 March 2020, authorising abortions to be carried out by a ‘registered medical professional’.[1][2][3]

In Great Britain abortion continues to be regulated under criminal law, but is legally available through the Abortion Act 1967, which permits abortions if there is:

- risk to the life of the pregnant woman;

- a necessity for abortion to prevent grave permanent injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman;

- risk of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman or any existing children of her family (up to a term limit of 24 weeks of gestation); or

- substantial risk that if the child were born, it would "suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped".[4][5]

In the past, abortion policy was devolved in Scotland and Northern Ireland but not in Wales. Provisions included in the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019, passed by Parliament at a time when the Northern Irish Assembly was not operating, legalized abortion, hitherto banned, in Northern Ireland. The legislation was passed on 21 October 2019 and the legalisation of the provision of abortion services came into force on 31 March 2020.[1][2] Beforehand, Northern Irish women could access abortion services in other parts of the UK without paying a fee and without committing a criminal offence.[6]

Great Britain

The main law on abortion in England, Scotland and Wales is the Abortion Act 1967, as amended by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990. In Great Britain, abortion is generally allowed for socio-economic reasons during the first twenty-four weeks of the pregnancy (higher than any country in the EU, apart from the Netherlands), and beyond for medical reasons.[7]

England and Wales

The Offences against the Person Act 1861, in England and Wales, prohibits administering drugs or using instruments to procure an abortion (section 58) and procuring drugs or other items to cause an abortion (section 59), although subsequent law has provided for a range of grounds which allow abortion to be widely available.

The Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 amended the law in England and Wales to create the offence of child destruction – in cases where any person “who, with intent to destroy the life of a child capable of being born alive, by any wilful act causes a child to die before it has an existence independent of its mother”. For the purposes of this Act, a child whose mother has been pregnant for 28 weeks is deemed “capable of being born alive”. The 1929 Act also provides a defence where it is proved that causing the death of the child was “done in good faith for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother.”[8]

The Abortion Act 1967 originally permitted abortion “by a registered medical practitioner if two registered medical practitioners are of the opinion, formed in good faith” on the following grounds:

- a risk to the life of the pregnant woman, or of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman or any existing children of her family; and

- a substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be “seriously handicapped”.[9]

The Act came into operation in 1968, and originally applied a term limit of 28 weeks, in line with the Infant Life Preservation Act.[10] It was subsequently amended by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990, to allow for the following grounds:[11]

- Ground A – risk to the life of the pregnant woman;

- Ground B – to prevent grave permanent injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman;

- Ground C – risk of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman (up to 24 weeks in the pregnancy);

- Ground D – risk of injury to the physical or mental health of any existing children of the family of the pregnant woman (up to 24 weeks in the pregnancy);

- Ground E – substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped;

- Ground F – to save the life of the pregnant woman; or

- Ground G – to prevent grave permanent injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman in an emergency.[12]

The amendment therefore allowed for a reduction in the term limit to 24 weeks for Ground C and Ground D with the law changing to reflect advances in technology to enable premature children to be born alive earlier in a pregnancy. However, no term limit was applied to other grounds and abortion was permitted throughout the pregnancy in these cases. The changes took effect in April 1991.[13]

Abortion law was not devolved to the National Assembly for Wales under Government of Wales Act 1998[14] and was specifically reserved to the UK Parliament via the Government of Wales Act 2006.[15]

Scotland

Abortion is an offence under common law in Scotland;[16] the Abortion Act 1967 (as amended) applies in Scotland[17] and refers to “any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion”.[18] The Scotland Act 1998, which established the Scottish Parliament, reserved abortion law to the UK Parliament [19] but it was subsequently devolved through the Scotland Act 2016.[20] The Abortion Act 1967 remains in place.

Proposed amendments

During each Parliament, several private members’ bills are generally introduced to seek to amend the law in relation to abortion.[21] In 2017, the Reproductive Health (Access to Terminations) Bill 2016-17[22] was introduced by Diana Johnson MP, during the term of office of then Prime Minister Theresa May; the bill aimed to repeal criminalised aspects of existing abortion law in England and Wales. However, with the call for a general election on the 8 June 2017, the bill fell and no further action was taken.[23] Minor amendments to the Abortion Act 1967 have been introduced through government legislation, the most recent being a reference to the new Department of Health and Social Care, in 2018.[24]

Interpretation

Section 58 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 reads as follows and prohibits administering drugs or using instruments to cause a miscarriage:

Every woman, being with child, who, with intent to procure her own miscarriage, shall unlawfully administer to herself any poison or other noxious thing, or shall unlawfully use any instrument or other means whatsoever with the like intent, and whosoever, with intent to procure the miscarriage of any woman whether she be or be not with child, shall unlawfully administer to her or cause to be taken by her any poison or other noxious thing, or unlawfully use any instrument or other means whatsoever with the like intent, shall be guilty of felony, and being convicted thereof shall be liable ... to be kept in penal servitude for life ...[25]

Section 59 of that Act reads as follows and prohibits the procurement of drugs or other items to cause a miscarriage:

Whosoever shall unlawfully supply or procure any poison or other noxious thing, or any instrument or thing whatsoever, knowing that the same is intended to be unlawfully used or employed with intent to procure the miscarriage of any woman, whether she be or be not with child, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and being convicted thereof shall be liable ... to be kept in penal servitude ...[26]

The following terms in the 1861 Act may be interpreted as follows:

- Unlawfully – for the purposes of sections 58 and 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861, and any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion, anything done with intent to procure a woman's miscarriage (or in the case of a woman carrying more than one foetus, her miscarriage of any foetus) is unlawfully done unless authorised by section 1 of the Abortion Act 1967 and, in the case of a woman carrying more than one foetus, anything done with intent to procure her miscarriage of any foetus is authorised by the said section 1 if the ground for termination of the pregnancy specified in subsection (1)(d) of the said section 1 applies in relation to any foetus and the thing is done for the purpose of procuring the miscarriage of that foetus, or any of the other ground for termination of the pregnancy specified in the said section 1 applies;[27]

- Felony and misdemeanor – see the Criminal Law Act 1967;

- Mode of trial – the offences under section 58 and 59 are indictable-only offences;

- Sentence – an offence under section 58 is punishable with imprisonment for life or for any shorter term[28] and an offence under section 59 is punishable with imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years.[29]

A death of a person in being which is caused by an unlawful attempt to procure an abortion, is at least manslaughter.[30][31]

The following terms in the 1967 Act may be interpreted as follows:

- The law relating to abortion – in England and Wales, this means sections 58 and 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 and any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion.[32] and in Scotland, this means any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion;[32]

- Terminated by a registered medical practitioner – see Royal College of Nursing of the UK v DHSS [1981] AC 800, [1981] 2 WLR 279, [1981] 1 All ER 545, [1981] Crim LR 322, HL;

- Place where termination must be carried out – see sections 1(3) to (4);

- The opinion of two registered medical practitioners – see section 1(4);

- Good faith – see R v Smith (John Anthony James), 58 Cr App R 106, CA;

- Determining the risk of injury in ss. (a) & (b) – see section 1(2);

- Risk, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated, of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman – In R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance, Lord Justice Laws said: "There is some evidence that many doctors maintain that the continuance of a pregnancy is always more dangerous to the physical welfare of a woman than having an abortion, a state of affairs which is said to allow a situation of de facto abortion on demand to prevail."[33]

As to the effect of section 6(1)(a) of the Broadcasting Act 1990 in relation to broadcasting pictures of an abortion, see R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance [2003] UKHL 23, [2004] 1 AC 185, [2003] 2 WLR 1403, [2003] 2 All ER 977, [2003] UKHRR 758, [2003] HRLR 26, [2003] ACD 65, [2003] EMLR 23, reversing R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance [2002] EWCA Civ 297, [2002] 3 WLR 1080, [2002] 2 All ER 756, CA. That section was repealed by the Communications Act 2003.

Northern Ireland

Statute law before 2019

Before significant changes in 2019, there were two main laws on abortion in Northern Ireland:

- the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 (sections 58 and 59) prohibited attempts to cause a miscarriage;

- the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1945 (sections 25 and 26) provided an exception for acting "in good faith for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother" and also created the offence of child destruction i.e. to cause a child to die "before it has an existence independent of its mother".

Civil and criminal law was devolved to Northern Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 (section 4) and the Northern Ireland Parliament enacted the 1945 legislation to introduce the same changes as the Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 had made in England and Wales. An integrated and state-funded health and social care service was established in 1948, complementing the National Health Service and also providing state-funded social services for mothers and children.

Devolution was suspended in 1972 and direct rule from Westminster continued until the transfer of a range of powers, including health, to the new Northern Ireland Assembly in 1999.[34][35] Criminal law, including abortion, continued to be overseen by Westminster until the devolution of policing and justice powers in 2010.[36]

Case law before 2019

Between 1993 and 1999, a series of court cases had interpreted the law as also allowing for abortion in cases where, for the pregnant woman, "there is a risk of real and serious adverse effect on her physical or mental health, which is either long term or permanent".[37][38][39]

In Northern Ireland Health and Social Services Board v A and Others [1994] NIJB 1, Lord Justice MacDermott said that he was "satisfied that the statutory phrase, 'for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother' does not relate only to some life-threatening situation. Life in this context means that physical or mental health or well-being of the mother and the doctor's act is lawful where the continuance of the pregnancy would adversely affect the mental or physical health of the mother. The adverse effect must however be a real and serious one and there will always be a question of fact and degree whether the perceived effect of non-termination is sufficiently grave to warrant terminating the unborn child."

In Western Health and Social Services Board v CMB and the Official Solicitor (1995, unreported), Mr Justice Pringle stated that "the adverse effect must be permanent or long-term and cannot be short term ... in most cases the adverse effect would need to be a probable risk of non-termination but a possible risk might be sufficient if the imminent death of the mother was a risk in question".[40]

In Family Planning Association of Northern Ireland v Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety (October 2004), Lord Justice Nicholson stated that "it is unlawful to procure a miscarriage where the foetus is abnormal but viable, unless there is a risk that the mother may die or is likely to suffer long-term harm, which is serious, to her physical or mental health".[41] In the same case, Lord Justice Sheil stated that "termination of a pregnancy based solely on abnormality of the foetus is unlawful and cannot lawfully be carried out in this jurisdiction".[42]

In November 2015, Lord Justice Horner made a declaration of incompatibility under the Human Rights Act 1998 to the effect that Northern Ireland's law on abortion (specifically its lack of provision in cases of fatal foetal abnormality or where the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest) could not be interpreted in a manner consistent with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights i.e. a right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence; the Convention also protects a right to life in Article 2.[43] In June 2017, the declaration of incompatibility was quashed by the Court of Appeal on the grounds that "a broad margin of appreciation must be accorded to the state" and "a fair balance has been struck by the law as it presently stands until the legislature decides otherwise".[44][45] In June 2018, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom held that the law of Northern Ireland was incompatible with the right to respect for private and family life, insofar as the law prohibited abortion in cases of rape, incest and fatal foetal abnormality. However, the court did not restore the declaration of incompatibility as it also held that the claimant did not have standing to bring the proceedings and accordingly the court had no jurisdiction to make a declaration of incompatibility reflect its view on the compatibility issues.[46][47] The judgments of the Supreme Court acknowledged that the court lacked jurisdiction to issue a declaration of incompatibility but included a non-binding opinion that an incompatibility existed, and that a future case in which the applicant had the necessary standing would be likely to succeed. It also urged the authorities "responsible for ensuring the compatibility of Northern Ireland law with the Convention rights" to "recognise and take account of these conclusions ... by considering whether and how to amend the law".[48][49]

During this time, abortion and child destruction offences were only occasionally recorded in Northern Ireland - a possible effect of the deterrent provided in law. Between 1998 and 2018, the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the Police Service of Northern Ireland recorded 17 cases of "procuring illegal abortion" and three cases of "intentional destruction of a viable unborn child". In several years within that timeframe, no offences of this type were recorded.[50]

Changes in law: 2019-2020

The law on abortion in Northern Ireland was changed by Parliament during a suspension of the Northern Ireland Executive, which took place between 2017 and 2020. Recommendations to liberalise abortion law in Northern Ireland were published in February 2018 by the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in the report of its Inquiry concerning the United Kingdom (under Article 8 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women).[51]

The Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019, enacted on 24 July 2019, extended the deadline for the restoration of the Executive to 21 October 2019. Under an private member’s amendment introduced by Stella Creasy MP, if an Executive were not restored by that date, the Act would:

- require the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland to implement recommendations regarding abortion made in the CEDAW report;[52]

- repeal sections 58 and 59 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 under the law of Northern Ireland;[53] and

- require the Secretary of State, by regulation, to make further changes in the law for complying with the recommendations with those regulations coming into force on 31 March 2020.[54]

On 21 October 2019, as a result of the Executive not being restored, sections 58 and 59 of the 1861 Act were repealed.[55] Legal protection for the life of a child who was "capable of being born alive" continued under the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1945.

The Executive was restored in January 2020 but legislation on abortion continued to be implemented through Westminster. The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020 were laid before Parliament on 25 March 2020 and took effect on 31 March 2020.[3][56][57]

The Regulations allowed for abortion in Northern Ireland in the following circumstances:

- where the pregnancy has not exceeded its twelfth week;[58]

- a risk of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman (up to a term limit of 24 weeks);[59]

- a risk to life or risk of grave permanent injury to physical or mental health of the pregnant woman;[60]

- a severe fetal impairment – "a substantial risk that if the child were born, it would suffer from such physical or mental impairment as to be seriously disabled" (with no term limit); or

- a fatal fetal abnormality – "a substantial risk that the death of the fetus is likely before, during or shortly after birth" (with no term limit).[61]

A person who intentionally terminates or procures the termination of a pregnancy other than in accordance with the Regulations commits an offence; this does not apply to a pregnant woman or where the act which caused the termination was done in good faith for the purpose only of saving the woman’s life or preventing grave permanent injury.[62] The 1945 Act remains in law, including the offence of child destruction, although this no longer applies to a pregnant woman, or a registered medical professional acting in accordance with the Regulations.[63]

The Regulations were replaced by the Abortion (Northern Ireland) (No. 2) Regulations 2020, which were materially the same with minor corrections; these came into force on 14 May 2020.[64]

Proposed amendments

In June 2020, the Northern Ireland Assembly voted – with 46 members in favour and 40 against – to reject "the imposition of abortion legislation that extends to all non-fatal disabilities, including Down's syndrome."[65] Following this vote, the Severe Fetal Impairment Abortion (Amendment) Bill – to remove the grounds for non-fatal disabilities – was introduced by Paul Givan MLA in February 2021. It reached its consideration stage in December 2021 but MLAs decided – by 45 votes to 43 – against the main proposal in the Bill at that stage.[66]

Political party approaches

Abortion, as with other sensitive issues, is regarded as a matter of conscience for parliamentarians within the main political parties in Great Britain. Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat and Scottish National Party MPs, for example, considered and individually decided to vote for or against several proposed changes in the term limit in 2008.[67]

Laws and policies relating in abortion have been regular issues of political debate in Northern Ireland in recent years.

The Democratic Unionist Party and Traditional Unionist Voice supported the pre-2019 law on abortion and opposed the legislative changes introduced through the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation) Act.[68][69] DUP MLA Paul Givan introduced the Severe Fetal Impairment Abortion (Amendment) Bill in 2021, which sought to remove the ground for an abortion in cases of a severe disability in the unborn child.

Sinn Féin policy, as approved by its annual conference in 2018, is for abortion to be available "where a woman’s life, health or mental health is at risk and in cases of fatal foetal abnormality" and "without specific indication ... through a GP led service in a clinical context as determined by law and licensing practice for a limited gestational period".[70] The Green Party in Northern Ireland and People Before Profit support the full decriminalisation of abortion (i.e. abortion being available for any reason).[71][72]

For the Social Democratic and Labour Party, the Ulster Unionist Party, and the Alliance Party, abortion is a matter of conscience, as is the case in Westminster.[73]

Christian and other faith perspectives

Churches and their members support women in crisis pregnancies and/or who have experienced a miscarriage or abortion through practical support and advice and counselling services, either through personal initiative, pastoral ministries, or through specific pro-life/anti-abortion charities. As in other countries, there is a wide range of individual views on abortion within church denominations.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that human life “must be respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception” and that from the first moment of existence, “a human being must be recognized as having the rights of a person - among which is the inviolable right of every innocent being to life.” The Church has affirmed “the moral evil of every procured abortion” since the first century and describes direct abortion “willed either as an end or a means” as gravely contrary to the moral law.[74]

The Church of England combines strong opposition to abortion with a recognition that there can be “strictly limited” conditions under which it may be morally preferable to any available alternative. This is based on its view that the foetus is a human life with the potential to develop relationships, think, pray, choose and love. The Church has suggested that the case for further reductions of the time limit for abortions should be “sympathetically considered on the basis of advances in neo-natal care” and has stated that every possible support, especially by church members, needs to be given to those who are pregnant in difficult circumstances.[75]

The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland regards the foetus as “from the beginning, an independent human being” and therefore it can be threatened “only in the case of threat to maternal life, and that after the exhaustion of all alternatives”.[76]

The Presbyterian Church in Ireland - the largest Protestant denomination in Northern Ireland - is strongly pro-life/anti-abortion, and maintains that abortion should only be permitted in exceptional circumstances (e.g. where there is a real and substantial risk to the life of the mother) subject to the most stringent safeguards. The Church has affirmed the sanctity of human life, that human life begins at conception, and that complex medical and social issues such as abortion need to be handled with sensitivity and compassion.[77]

The Church of Ireland - a member of the Anglican Communion alongside the Church of England - affirms that "every human being is created with intrinsic dignity in the image of God with the right to life." It has opposed "extreme abortion legislation" imposed on Northern Ireland, asked that legislation is developed that safeguards the well-being of both the mother and unborn child, and encourahed its members to provide more support to mothers during pregnancy, particularly during times of crisis.[78] In relation to potential grounds for abortion, the Church recognises that there are "exceptional circumstances of strict and undeniable medical necessity where an abortion should be an option (or more rarely a necessity).[79]

The Conference of the Methodist Church of Great Britain stated in 1976 that the human foetus had “an inviolable right to life” and that abortion should never be seen as an alternative to contraception. The Church also recognised that foetus is “totally dependent” on his or her mother for at least the first twenty weeks of its life and said that the mother has “a total right to decide whether or not to continue the pregnancy.” The Church has supported counselling opportunities for mothers so that they fully understand the decision, and the alternatives to abortion.[80]

Its sister church, the Methodist Church in Ireland, is opposed to abortion on demand and urges support and resources for those who have a crisis pregnancy. The Church recognises that there are complex situations "in which early termination of pregnancy should be available" and considers that these include "when a mother’s life is at risk, when a pregnancy is the result of a sexual crime, or in cases of fatal foetal abnormality."[81] The smaller Protestant churches are generally conservative on the issue of abortion.[82][83]

Congregations and members of major non-Christian religions in the UK likewise provide pastoral support for women, families and children whose circumstances are affected by crisis pregnancies and abortion, in a range of ways. Views on the morality and potential grounds for abortion vary within Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Judaism.

Campaign groups

Prominent campaign groups which are supportive of a conservative policy include Both Lives Matter, Christian Action Research and Education (CARE), Evangelical Alliance, and the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children (SPUC). Campaigners in support of a liberal policy include Amnesty International, the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS), the Family Planning Association (FPA), Marie Stopes, and Humanists UK.

Abortion policy in Northern Ireland was the subject of intense discussion and campaigning in the decade leading up to changes in the law in 2019 and 2020. The issue is debated less frequently in Great Britain, where the law was last substantially changed in 1990.

The English left-wing journalist Polly Toynbee described the previous law in Northern Ireland as discriminatory against women as it "forbids them from having an abortion in their own home country".[84] However, Bernadette Smyth, the leader of the Precious Life group, has said: "Women's health is not in danger. Women are not dying because they cannot get abortion."[85]

At its 2012 conference, Sinn Féin adopted a policy of allowing abortion in both parts of Ireland under certain circumstances; this was superseded by a newer policy adopted at its 2018 conference.[86] The then deputy First Minister, Martin McGuinness, had stated: "Sinn Féin is not in favour of abortion, and we resisted any attempt to bring the British 1967 Abortion Act to the North."[87]

Under Dawn Purvis, the Progressive Unionist Party provided strong support for the establishment of an independent Marie Stopes abortion clinic in Belfast in 2012.[87]

In March 2013, a DUP representative in the Northern Ireland Assembly, Jim Wells, proposed an amendment to the law "to restrict lawful abortions to NHS premises, except in cases of urgency when access to NHS premises is not possible and where no fee is paid".[88] In response, Amnesty International asked the Assembly's Justice Committee to reject the full amendment, claiming that "the restrictive abortion laws and practices and barriers to access safe abortion are gender-discriminatory, denying women and girls treatment only they need".[89]

Following a United Nations report in July 2013, a Liberal Democrat junior minister in the then UK Coalition Government, Jenny Willott, stated that the Government was obliged to submit a report on the steps taken to implement recommendations on abortion laws and services in Northern Ireland by November 2014.[90] The Labour and Liberal Democrat parties do not contest elections in Northern Ireland).

In September 2014, the then Democratic Unionist Party Health Minister, Jim Wells, was quoted by The Guardian regarding abortion in cases of rape. Mr Wells stated: "That is a tragic and difficult situation but should the ultimate victim of that terrible act – which is the child – should he or she be punished for what has happened by having their life terminated? No."[91]

During his tenure as leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, Mike Nesbitt remarked in October 2014: "My view is that we need a consultation and that a woman's voice should be stronger by a long way in that consultation."[92] An SDLP representative at that time, Fearghal McKinney, stated that he was fundamentally opposed to any extension of the Abortion Act 1967 to Northern Ireland.[92]

An Amnesty International poll in 2014 indicated that a majority of people in Northern Ireland appeared to agree with changes in abortion law in three particular situations i.e. where a pregnancy has occurred due to rape, or incest, or where a fatal foetal abnormality (or life-limiting condition) has been diagnosed in the unborn child.[93]

The Justice Minister in the Northern Ireland Executive, David Ford (a member of the Alliance Party) subsequently issued a public consultation on amending the criminal law on abortion; the consultation opened in October 2014 and closed in January 2015. The call for consultation took into consideration cases where "there is a diagnosis in pregnancy that the foetus has a lethal abnormality".[94] and cases where "women have become pregnant as a result of sexual crime".[94] However, Mr Ford also wrote that "it is not a debate on the wider issues of abortion law – issues often labelled as 'pro-choice' and 'pro-life'".[94]

David Ford subsequently introduced the Abortion (Fatal Foetal Abnormalities) Bill in December 2016. This would have allowed terminations up to 24 weeks of gestation in those cases. The Bill fell with the collapse of the Northern Ireland Executive in January 2017.[95]

Crown dependencies

Although Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man are not part of the United Kingdom, as they are part of the Common Travel Area, people resident on these islands who choose to have an abortion have travelled to the UK since the Abortion Act 1967.[96]

Jersey

It is lawful in Jersey to have an abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy if the woman is in "distress" and requests it;[97][98] in the first 24 weeks in case of foetal abnormalities; and at any time to save the woman's life or prevent serious permanent injury to her health. The criteria were established in the Termination of Pregnancy (Jersey) Law 1997.[99]

Guernsey

It is lawful in Guernsey to have an abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy so long as specific criteria are met;[100] in the first 24 weeks in case of foetal abnormalities; and at any time to save the woman's life or prevent serious permanent injury to her health. The criteria were established in the Abortion (Guernsey) Law 1997.[101]

The Guernsey law of 1997 does not apply to Alderney and Sark,[101] which are also part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey but continue to apply an earlier law, in French, identical to the Offences against the Person Act 1861 of England and Wales, which does not explicitly mention any legal ground for abortion.[102] However, the judicial decision Rex v. Bourne in England and Wales clarified that the law always implicitly allowed abortion at least to save the woman's life, and the decision extended it also to preserve her health.[103] It is unclear whether Alderney and Sark apply only the original legal principle or also the extension by the judicial decision.

Isle of Man

Since 24 May 2019,[104] it is lawful in the Isle of Man to have an abortion during the first 14 weeks of pregnancy at will, then until the 24th week, so long as criteria specified by the act are met, and then onwards if there is a serious risk of grave injury or death. Abortion is governed by the Abortion Reform Act 2019.[105]

History

Abortion was dealt with by the ecclesiastical courts in England, Scotland and Wales. Until the Reformation it was dealt with under the laws of the Catholic Church. The ecclesiastical courts dealt mainly with the issue due to problems of evidence in such cases. The ecclesiastical courts had wider evidential rules and more discretion regarding sentencing.[106] Although the ecclesiastical courts heard most cases of abortion, some cases such as the Twinslayers Case were heard in the secular courts. The old ecclesiastical courts were made defunct after the Reformation.

Later, under Scottish common law, abortion was defined as a criminal offence unless performed for "reputable medical reasons", a definition sufficiently broad as to essentially preclude prosecution.

The law on abortion started to be codified in legislation and dealt with in the courts of the state under sections 1 and 2 of Lord Ellenborough's Act (1803). The offences created by this statute were replaced by section 13 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1828. Under section 1 of the 1803 Act and the first offence created by section 13 of the 1828 Act, the crime of abortion was subject, in cases where the woman was proved to have been quick with child, to the death penalty or penal transportation for life. Under section 2 of the 1803 Act and the second offence created by section 13 of the 1828 Act (all other cases), the penalty was transportation for 14 years.

Section 13 of the 1828 Act was replaced by section 6 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1837. This section made no distinction between women who were quick with child and those who were not. It eliminated the death penalty as a possible punishment.

Transportation was abolished by the Penal Servitude Act 1857, which replaced it with penal servitude.

Section 6 of the 1837 Act was replaced by section 58 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861. Section 59 of that created a new preparatory offence of procuring drugs or instruments with intent to procure abortion.

From 1870, there was a steady decline in fertility, linked not to a rise in the use of artificial contraception but to more traditional methods such as withdrawal and abstinence.[107] This was linked to changes in the perception of the relative costs of childrearing. Of course, women did find themselves with unwanted pregnancies. Abortifacients were discreetly advertised and there was a considerable body of folklore about methods of inducing miscarriages. Amongst working-class women, violent purgatives were popular: pennyroyal, aloes and turpentine were all used. Other methods to induce miscarriage were very hot baths and gin, extreme exertion, a controlled fall down a flight of stairs, or veterinary medicines. So-called "backstreet" abortionists were fairly common, although their efforts could be fatal. Estimates of the number of illegal abortions varied widely; by one estimate, 100,000 women made efforts to procure an abortion in 1914, usually by drugs.

The criminality of abortion was redoubled in 1929, when the Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 was passed. The Act criminalised the deliberate destruction of a child "capable of being born alive". This was to close a lacuna in the law, identified by Lord Darling, which allowed for infants to be killed during birth, which would mean that the perpetrator could neither be prosecuted for abortion or murder.[108] There was included in the Act the presumption that all children in utero over 28 weeks' gestation were capable of being born alive. Children in utero below this gestation were dealt with by way of evidence presented to determine whether or not they were capable of being born alive. In 1987, the Court of Appeal refused to grant an injunction to stop an abortion, ruling that a foetus between 18 and 21 weeks was not capable of being born alive.[109][110] In May 2007, a woman from Levenshulme, Manchester, who had an illegal late-term abortion at 7+1⁄2 months in early 2006 was convicted of child destruction under the Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929.[111]

The pro-choice group the Abortion Law Reform Association was formed in 1936.

In 1938, the decision in R v. Bourne[112] allowed for further considerations to be taken into account. This case related to an abortion performed on a girl who had been raped. It extended the defence to abortion to include "mental and physical wreck" (Lord Justice McNaghtan). The gynaecologist concerned, Aleck Bourne, later became a founder member of the pro-life/anti-abortion group Society for the Protection of Unborn Children (SPUC)[113] in 1966.

In 1939 the Birkett Committee recommended a change to abortion laws, but the intervention of World War II meant that all plans were shelved. Post-war, after decades of stasis, certain high-profile tragedies, including thalidomide, and social changes brought the issue of abortion back into the political arena.

The 1967 Act

The Abortion Act 1967 sought to clarify the law. Introduced by David Steel and subject to heated debate, it allowed for legal abortion on a number of grounds, with the added protection of free provision through the National Health Service. The Act was passed on 27 October 1967 and came into effect on 27 April 1968.[114]

Before the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 amended the Act, the Infant Life Preservation Act 1929 acted as a buffer to the Abortion Act 1967. This meant that abortions could not be carried out if the child was "capable of being born alive". There was therefore no statutory limit put into the Abortion Act 1967, the limit being that which the courts decided as the time at which a child could be born alive. The C v S case in 1987 confirmed that, at that time, between 19 and 22 weeks a foetus was not capable of being born alive.[109] The 1967 Act required that the procedure must be certified by two doctors before being performed.

Proposals and laws since 1967

In the years following the 1967 Act, Members of Parliament have introduced a number of private member's bills to change the abortion law. Four resulted in substantive debate (1975,[115] 1976,[116] 1979,[117] 1988,[118] and 1990[119]) but all failed. The Lane Committee investigated the workings of the Act in 1974 and declared its support.

Changes to the Abortion Act 1967 were introduced in Parliament through the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990. The time limits were lowered from 28 to 24 weeks for most cases on the grounds that medical technology had advanced sufficiently to justify the change. Restrictions were removed for late abortions in cases of risk to life, foetal abnormality, or grave physical and mental injury to the woman. Some Members of Parliament claimed not to have been aware of the vast change that the decoupling of the Infant Life Preservation Act 1929 would have on the Abortion Act 1967, particularly in relation to the unborn disabled child.

Politicians from the unionist and nationalist parties in Northern Ireland joined forces in June 2000 to block any extension of the Abortion Act 1967 to Northern Ireland where terminations were allowed on a restricted basis.[120]

There was widespread action by pro-choice groups to oppose any attempts to restrict abortion[121][122][123] via the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill (now Act) in Parliament (Report Stage and Third Reading, 22 October 2008[124]). MPs voted to retain the current legal limit of 24 weeks. Amendments proposing reductions to 22 weeks and 20 weeks were defeated by 304 to 233 votes and 332 to 190 votes respectively.[125]

A number of pro-choice amendments were proposed by the Labour MPs Diane Abbot,[126] Katy Clark and John McDonnell,[127] including NC30 Amendment of the Abortion Act 1967: Application to Northern Ireland.[128] However, it was reported that the Labour government at the time asked MPs not to table these amendments (and at least until Third Reading) and then allegedly used parliamentary mechanisms in order to prevent a vote.[129]

In May 2017, the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership made a commitment to extend the Abortion Act 1967 to Northern Ireland.[130][131] In June 2017, the UK Government revealed plans to provide some type of free abortion services in England for women from Northern Ireland in an attempt to avoid a Conservative rebellion in a vote on the Queen's Speech in the context of the Conservative–DUP agreement.[132]

Statistics

Legal abortions by ground

Statistics for legal abortions are published annually by the Department of Health and Social Care, for England and Wales, NHS Scotland, and the Department of Health in Northern Ireland. Where there is only a small number of abortions for a particular ground, the number is not published by statisticians to avoid the risk of disclosing the identity of the persons involved.

Legal abortions were carried out on the following grounds in England and Wales in 2020:

| Primary ground | Number | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grounds A/F/G | 98 | 0.05 | Risk to life of pregnant woman (or in emergencies) |

| Ground B | 31 | 0.01 | Prevent grave permanent injury to pregnant woman |

| Ground C | 206,768 | 98.1 | Risk of injury to physical/mental health of pregnant woman |

| Ground D | 778 | 0.37 | Risk of injury to physical/mental health of other children |

| Ground E | 3,185 | 1.51 | Physical or mental abnormality in unborn child |

| Total | 210,860 | 100.0 |

The vast majority (99.9%) of abortions carried out under Ground C alone were reported as being performed because of a risk to the woman's mental health and were classified as F99 (mental disorder, not otherwise specified) under the ICD-10 classification system.[133]

Legal abortions were carried out on the following grounds in Scotland in the same year:

| Primary ground | Number | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grounds A/B/D/F/G | 34 | 0.25 | Risk to life of pregnant woman (and other grounds not listed below) |

| Ground C | 13,572 | 98.2 | Risk of injury to physical/mental health of pregnant woman |

| Ground E | 209 | 1.51 | Physical or mental abnormality in unborn child |

| Total | 13,815 | 100.0 |

In Northern Ireland, the total number of terminations in 2017-2018 was 12, followed by 8 in 2018-2019, and 22 in 2019-2020.[134][135] As indicated above, for most of that time, abortions were permitted there if the act was to save the life of the mother, or if there was a risk of permanent and serious damage to the mental or physical health of the mother.

In 2020, a total of 371 women travelling from Northern Ireland received abortions in England and Wales:

- 367 – due to risk of injury to physical or mental health of the pregnant woman; and

- 4 – due to physical or mental abnormality in the unborn child.[136]

In the same year, 194 women travelling from the Republic of Ireland received abortions in England and Wales:

- 131 – due to risk of injury to physical or mental health of the pregnant woman; and

- 63 – due to physical or mental abnormality in the unborn child.[137]

The number of pregnant women from the island of Ireland travelling for an abortion was previously much more significant although this decreased following changes in legislation in both Northern Ireland and the Republic, and travel restrictions during the Covid-19 pandemic. Scottish statistics for abortion record the place of residence of the pregnant woman within Scotland (i.e. an NHS board or a local government area); these figures includes temporary addresses for students and a small number of women travelling to Scotland from elsewhere.[138]

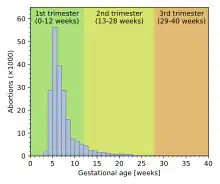

Legal abortions by gestation

A significant majority of abortions in Great Britain take place at less than 10 weeks of gestation. The numbers and percentages in England and Wales, Scotland, and Great Britain overall, were as follows in 2020. Information on gestation and abortion is not available in Northern Ireland for the same year.

| Gestation | England and Wales | % | Scotland | % | Great Britain | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–9 weeks | 185,559 | 88.0 | 12,108 | 87.6 | 197,667 | 88.0 |

| 10–12 weeks | 11,654 | 5.5 | 983 | 7.1 | 12,637 | 5.6 |

| 13–19 weeks | 10,736 | 5.4 | 651 | 4.7 | 11,387 | 5.1 |

| 20 weeks and over | 2,911 | 1.4 | 73 | 0.5 | 2,984 | 1.3 |

| Total | 210,860 | 100 | 13,815 | 100 | 224,675 | 100 |

Legal abortions by nation/region

In 2020, the region with the largest number of abortions was London followed by South East England, the West Midlands and North West England. Statistics on abortion recorded at a regional level or national level (for England, Wales and Scotland individually) relate to residents. Abortions for non-residents are also recorded for England and Wales (collectively) although these were lower than usual (at 943 abortions) in that year due to travel restrictions during the Covid-19 pandemic. Information for Northern Ireland is recorded by financial year rather than calendar year, with 22 abortions recorded in 2019-2020.

| Nation/Region | No. of abortions |

|---|---|

| London | 42,630 |

| South East England | 28,723 |

| South West England | 15,008 |

| East of England | 19,819 |

| West Midlands | 23,159 |

| East Midlands | 14,806 |

| North West England | 29,927 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 18,013 |

| North East England | 7,998 |

| England | 200,083 |

| Wales | 9,834 |

| England and Wales (residents) | 209,917 |

| England and Wales (non-residents) | 934 |

| Scotland | 13,815 |

| Great Britain | 224,675 |

Abortion offences

In the decade between 2009–2010 and 2019–2020 inclusive, Home Office statistics in England and Wales recorded:

- 61 cases of procuring abortion (under the Offences against the Person Act);

- 80 cases of intentional destruction of viable unborn child (child destruction, under the Infant Life Preservation Act).[139]

Guidance from the Crown Prosecution Service, in England and Wales, lists procuring an abortion (unlawfully) as a child abuse offence[140] and notes that some unlawful abortions may be carried out as honour-based crimes, which are committed to punish women for “alleged or perceived breaches of the family and/or community’s code of behaviour.”[141]

Trends since 1967

Post 1967 there was a rapid increase in the annual number of legal abortions, and a decline in sepsis and death due to illegal abortions.[142] In 1978 121,754 abortions were performed on women resident in the UK, and 28,015 on non-resident women.[143] The rate of increase fell from the early 1970s and actually dipped from 1991 to 1995 before rising again. The age group with the highest number of abortions per 1000 is amongst those aged 20–24. 2006 statistics for England and Wales revealed that 48% of abortions occurred to women over the age of 25, 29% were aged 20–24; 21% aged under 20 and 2% under 16.[144]

In 2004, there were 185,415 abortions in England and Wales. 87% of abortions were performed at 12 weeks or less and 1.6% (or 2,914 abortions) occurred after 20 weeks. Abortion is free to residents;[142] 82% of abortions were carried out by the public tax-funded National Health Service.[145]

The overwhelming majority of abortions (95% in 2004 for England and Wales) were certified under the statutory ground of risk of injury to the mental or physical health of the pregnant woman.[145]

By 2009 the number of abortions had risen to 189,100. Of this number, 2,085 are as a result of doctors deciding that there is a substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped.[146]

In a written answer to Jim Allister, the Northern Ireland health minister Edwin Poots disclosed that 394 abortions were carried out in Northern hospitals for the period 2005/06 to 2009/10 with the footnote that reasons for abortions were not gathered centrally.[147]

190,800 abortions were notified as taking place in England and Wales in 2013. 0.2% fewer than in 2012; 185,331 were to residents of England and Wales. The age-standardised rate was 15.9 abortions per 1,000 resident women aged 15–44 years; this rate increased from 11.0 in 1973, peaked at 17.9 in 2007, and fell to 15.9 in 2013.[148] For comparison, the EU average is only 4.4 abortions per 1,000 women in child-bearing age.[149]

Since approval of abortion in the UK in 1967 to 2014, 8,745,508 abortions have been performed.

In 2018, the total abortions in England and Wales was 205,295. In this year, the abortion rate was highest for those of the age of 21, and 81% were for those who were single.[150]

Attitudes to abortion (Great Britain)

Opinion polling occasionally considers public attitudes to the availability of abortion in Britain, which are often compared with respondents' voting habits for the main UK political parties. According to a 2004 The Times/Populus survey, feelings on abortion were:[151]

- 75% - abortion should be legal

- 38% - "always" legal

- 36% - "mostly" legal

- 23% - abortion should be illegal

- 20% - "mostly" illegal

- 4% - "always" illegal

A further YouGov/Daily Telegraph survey in August 2005 indicated: gestational age[152]

- 2% - supported abortion being available throughout pregnancy

- 25% - supported maintaining the term limit of 24 weeks

- 30% - would back a measure to reduce the limit to 20 weeks

- 19% - would support a limit of 12 weeks

- 9% - would support a limit of fewer than 12 weeks

- 6% - responded that abortion should never be allowed

A 2011 poll by MORI[153] surveyed women's attitudes to abortion.

Asked if a woman wants an abortion, she should not have to continue with her pregnancy:

- 53% agreed

- 15% agreed very strongly

- 12% agreed strongly

- 27% agreed

- 22% neither agreed nor disagreed

- 17% disagreed

- 8% disagreed

- 3% disagreed strongly

- 5% disagreed very strongly

- 5% did not know

- 3% preferred not to answer

Asked if too many women do not think hard enough before having an abortion:

- 37% agreed

- 8% agreed very strongly

- 8% agreed strongly

- 21% agreed

- 26% Neither agreed nor disagreed

- 28% Disagreed

- 16% Disagreed

- 7% Disagreed strongly

- 5% Disagreed very strongly

- 6% Did not know

- 3% Preferred not to answer

Asked if it should be made more difficult for women to obtain abortions

- 23% Agreed

- 7% agreed very strongly

- 4% agreed strongly

- 12% agreed

- 23% neither agreed nor disagreed

- 46% disagreed

- 25% disagreed

- 9% disagreed strongly

- 12% disagreed very strongly

- 6% did not know

- 2% preferred not to answer

Approved methods

Methodology is time-related. Up to the ninth week medical abortion can be used (mifepristone was approved for use in Britain in 1991); from the seventh up to the fifteenth week suction or vacuum aspiration is most common (largely replacing the more damaging dilation and curettage technique); for the fifteenth to the eighteenth weeks surgical dilation and evacuation is most common. Approximately 30% of abortions are performed medically.[142]

In 2011, BPAS lost a High Court bid to force the Health Secretary to allow women undertaking early medical abortions in England, Scotland and Wales to administer the second dose of drug treatment at home.[154] Though this decision that was later reversed in 2019, permitting women to undertake both pills at home.[155]

See also

- Abortion

- Abortion law

- Abortion debate

- Lobbying in the United Kingdom

- Halsbury's Laws of England

- Halsbury's Statutes

- Religion and abortion

General bibliography

- Ormerod, David; Hooper, Anthony (2011), "Homicide and related offences: abortion", in Ormerod, David; Hooper, Anthony, eds. (13 October 2011). Blackstone's criminal practice, 2012. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 226–230. ISBN 9780199694389.

- Richardson, P.J., ed. (1999). Archbold: criminal pleading, evidence and practice. London: Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 9780421637207. Chapter 19. Section III. Paras 19-149 to 19–165.

- Ormerod, David C. (2011), "Section 16.5 Further homicide and related offences: Child destruction and abortion", in Ormerod, David C. (ed.), Smith and Hogan's criminal law (13th ed.), Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 602–615, ISBN 9780199586493.

- Card, Richard (1992), "Abortion law", in Card, Richard; Cross, Rupert; Jones, Philip (eds.), Criminal law (12th ed.), London: Butterworths, pp. 230–235, ISBN 9780406000866.

Citations

- 1 2 Simpson, Claire; McHugh, Michael (31 March 2020). "New abortion laws allow unrestricted terminations up to 12 weeks". The Irish News.

- 1 2 ITV Report (31 March 2020). "New abortion laws come into force in Northern Ireland". ITV News.

- 1 2 "The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ↑

This article incorporates text published under the British Open Government Licence v3.0: "Abortion Act 1967 (section 1)". www.legislation.gov.uk. UK National Archives. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

This article incorporates text published under the British Open Government Licence v3.0: "Abortion Act 1967 (section 1)". www.legislation.gov.uk. UK National Archives. Retrieved 6 July 2019. - ↑ Participation, Expert. "Offences Against the Person Act 1861". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ "NI abortion: Guidelines issued ahead of 21 October deadline". BBC News. 8 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ↑ "Malta now only EU country without life-saving abortion law". The Malta Independent.

- ↑ "Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Abortion Act 1967, section 1 (as enacted)". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Abortion Act 1967, section 5 (as enacted)". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Abortion Act 1967, section 1 (as amended)". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Abortion statistics England and Wales 2020, Statutory grounds for abortion". www.gov.uk. Department of Health and Social Care. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Abortion statistics England and Wales 2020, Key events". www.gov.uk. Department of Health and Social Care. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Government of Wales Act 1998, Schedule 2". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ "Government of Wales Act 2006, Schedule 7A, Head J, Section J1". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ "Recorded Crime in Scotland 2019-2020, Classification of crimes and offences". www.gov.scot. Scottish Government. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Abortion Act 1967, section 7 (with geographical extent)". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Abortion Act 1967, section 6". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Scotland Act 1998, Schedule 5, Head J, J1". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ "Scotland Act 2016, section 53". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ "Find a Bill (bill titles including 'abortion')". www.parliament.uk. UK Parliament. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Reproductive Health (Access to Terminations) Bill 2016-17 — UK Parliament". services.parliament.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ↑ Arnull, Liam (2018). "How Brexit Stopped Abortion Being Decriminalised In England And Wales". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ↑ "Abortion Act 1967, reference F11". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ Revised text of section 58 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861. Legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ Revised text of section 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861. Legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ The Abortion Act 1967, section 5(2); as read with section 6

- ↑ The Offences against the Person Act 1861 (24 & 25 Vict c 100), section 58; the Criminal Justice Act 1948 (11 & 12 Geo 6 c 58), section 1(1)

- ↑ The Offences against the Person Act 1861 (24 & 25 Vict c 100), section 59; the Penal Servitude Act 1891 (54 & 55 Vict c 69), section 1(1); the Criminal Justice Act 1948 (11 & 12 Geo 6 c 58), section 1(1)

- ↑ R v Buck and Buck, 44 Cr App R 213, Assizes, per Edmund Davies J.; R v Creamer [1966] 1 QB 72, 49 Cr App R 368, [1965] 3 WLR 583, [1965] 3 All ER 257, CCA

- ↑ See also Attorney General's Reference (No 3 of 1994) [1998] AC 245, [1997] 3 WLR 421, HL, [1996] 1 Cr App R 351, CA.

- 1 2 The Abortion Act 1967, section 6

- ↑ R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance [2002] EWCA Civ 297 at [6], [2002] 2 All ER 756 at 761, CA

- ↑ "Devolution settlement: Northern Ireland". gov.uk. HM Government. 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Grosios, K.; Gahan, P. B.; Burbidge, J. (2010). "Overview of healthcare in the UK". The EPMA Journal. 1 (4): 529–534. doi:10.1007/s13167-010-0050-1. PMC 3405352. PMID 23199107.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Act 1998 (Amendment of Schedule 3) Order 2010, Explanatory Note". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ↑ "Guidance for HSC professionals on termination of pregnancy in Northern Ireland" (PDF). www.health-ni.gov.uk. Department of Health (Northern Ireland). 24 March 2016. pp. 36–37. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ↑ R v Bourne [1939] 1 KB 687

- ↑ Family Planning Association of Northern Ireland v Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety [2004] NICA 39 at paragraph [51], per Nicholson LJ

- ↑ Quoted by Nicholson LJ at paragraph 56 of Family Planning Association of Northern Ireland v Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety [2004] NICA 39

- ↑ "Family Planning Association of Norther Ireland v. The Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety (ref: 2004 NICA 39)". Northern Ireland Court of Appeal (NICA). 8 October 2004.

- ↑ "Family Planning Association of Norther Ireland v. The Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety (ref: 2004 NICA 37)". Northern Ireland Court of Appeal (NICA). 8 October 2004.

- ↑ The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission's Application [2015] NIHC 96 (QB), [2015] NIQB 96 (30 November 2015), High Court (Northern Ireland)

- ↑ Attorney General for Northern Ireland & The Department for Justice v The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission [2017] NICA 42 (29 June 2017), Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland (Northern Ireland)

- ↑ McDonald, Henry (29 June 2017). "Northern Irish appeal court refuses limited lifting of abortion ban". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ "In the matter of an application by the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland)" (PDF). www.supremecourt.uk. The Supreme Court. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ "Supreme Court rules Northern Ireland's abortion law breaches human rights but rejects challenge on technical grounds". The Independent. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ↑ "'All eyes are now on Government' after Supreme Court rule Northern Ireland abortion laws 'incompatible' with human rights laws". Belfast Telegraph. 7 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ Human Rights Commission for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland: Abortion) [2018] UKSC 27 (7 June 2018), Supreme Court (United Kingdom)

- ↑ "Police recorded crime Annual Trends 1998/99 to 2017/18". Police Service of Northern Ireland. 2018. Table 2.2. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ↑ Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) (23 February 2018). "Report of the inquiry concerning the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland under article 8 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women". www.ohchr.org. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019, section 9, clauses (1)&(10)". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019, section 9, clauses (2) & (3)". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019, section 9, clauses (4), (5) & (6)". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland abortion and same-sex marriage laws change". Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ↑ McCormack, Jayne (25 March 2020). "NI to offer unrestricted abortion up to 12 weeks". BBC News. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ↑ "Changes to the law in Northern Ireland: updated information". GOV.UK. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ↑ "The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020, clause 3". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020, clause 4". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020, clause 5 & clause 6". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020, clause 7". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020, clause 11". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "The Abortion (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2020, clause 13". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "The Abortion (Northern Ireland) (No. 2) Regulations 2020". www.legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Official Report, 2 June 2020". www.niassembly.gov.uk. Northern Ireland Assembly. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Severe Fetal Impairment Abortion (Amendment) Bill". www.niassembly.gov.uk. Northern Ireland Assembly. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill — proposed changes in abortion limit from 24 weeks". www.publicwhip.org.uk. The Public Whip. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland (Executive Formation) Bill". www.publicwhip.org.uk. The Public Whip. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ↑ TUV Northern Ireland Assembly election manifesto (PDF). Belfast: TUV. 2017. p. 16.

- ↑ "Sinn Féin Ard Fheis 2018, Motion 93, Ard Chomhairle". www.sinnfein.ie. Sinn Féin. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ↑ A Green Manifesto for Northern Ireland (PDF). Belfast: Green Party. 2017. p. 13.

- ↑ People Before Profit Assembly Election Manifesto 2017 (PDF). Belfast: People Before Profit. 2017. pp. 20–21.

- ↑ McClafferty, Enda (19 May 2018). "SDLP members support conscience vote on abortion matters". BBC. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, Respect for Human Life". www.vatican.va. Catholic Church. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ↑ "Abortion: Church of England Statements (summary paper)" (PDF). www.churchofengland.org. Church of England. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ↑ Robertson, David (26 August 2017). "Abortion, the Church of Scotland and the Media". The Wee Flea. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ↑ Presbyterian Church in Ireland (2013). "Presbyterians call for Pro Life Abortion Policy with stringent safeguards for exceptional cases". www.presbyterianireland.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "Statement of the Standing Committee on Northern Ireland abortion law and support for women in pregnancy". www.ireland.anglican.org. Church of Ireland. 15 June 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ↑ Church and Society Commission (2015). "Response to NI Abortion Legislation Consultation" (PDF). Church of Ireland. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "Views of the Church: Abortion and contraception". www.methodist.org.uk. Methodist Church of Great Britain. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ↑ "Practical Expressions of Methodist Belief". Methodist Belief (PDF). Methodist Church in Ireland. 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ↑ Ian Paisley, Leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (27 May 1993). "Early-day Motions". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 1023–1024.

- ↑ Public Morals Committee, Reformed Presbyterian Church (2008). "Abortion". www.rpc.org. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ↑ "Time for change in Northern Ireland". fpa.org.uk. Family Planning Association.

- ↑ AP (18 October 2012). "Protests as Ireland's 1st abortion clinic opens". USA Today.

- ↑ McDonald, Henry (7 March 2015). "Sinn Féin drops opposition to abortion at Derry congress". The Guardian.

- 1 2 Harkin, Shaun (5 December 2012). "The struggle for abortion rights in Ireland". Socialist Worker.

- ↑ Jim Wells, Member of the Northern Ireland Assembly for South Down (5 March 2013). "Amendment, new clause 'Ending the life of an unborn child' (Criminal Justice Bill Marshalled List of Amendments Further Consideration Stage)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Northern Ireland: Northern Ireland Executive. Archived 3 November 2014.

- ↑ Justice Act – Jim Wells' amendment: Submission to the Northern Ireland Assembly Justice Committee (PDF). Amnesty International. September 2014.

- ↑ "UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women: Women and Equalities written question – answered on 31st March 2014". theyworkforyou.com. They Work For You. 31 March 2014.

- ↑ McDonald, Henry (23 September 2014). "Northern Ireland gets health minister who opposes abortion for raped women". The Guardian.

- 1 2 Rainey, Mark (22 October 2014). "Seven out of 10 people in NI back a relaxation of abortion law – survey". News Letter. Belfast, Northern Ireland.

- ↑ Millward Brown (October 2014). Attitudes to abortion (PDF). Amnesty International.

- 1 2 3 The Criminal Law on Abortion – Lethal Foetal Abnormality and Sexual Crime: A Consultation on Amending the Law by the Department of Justice (PDF). Department of Justice, Northern Ireland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2014.

- ↑ Staff writer (14 March 2017). "Ford resubmits private member's bill on abortion reform". allianceparty.org. Alliance Party of Northern Ireland.

- ↑ Stephen Dorrell, Under-Secretary for Health (26 July 1990). "Written Answers: HEALTH – Abortion". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 428–429.

- ↑ Peters, Claire (21 May 2008). "Abortion law in Jersey". BBC News.

- ↑ Lakeman, Christopher (June 1997). "The concept of "distress" in the Termination of Pregnancy (Jersey) Law, 1997". Jersey and Guernsey Law Review. 1 (2). Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Termination of Pregnancy (Jersey) Law 1997, Jersey Legal Information Board, 2019.

- ↑ "1996: Guernsey votes to legalise abortion". BBC News. 13 June 1996.

- 1 2 Abortion (Guernsey) Law, 1997, Guernsey Legal Resources.

- ↑ Law on abortion, Guernsey Legal Resources, 1910. (in French)

- ↑ Rex v. Bourne, Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, 18–19 July 1938.

- ↑ "Isle of Man Government – Island's progressive abortion reforms in operation from today". www.gov.im. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ↑ "Abortion Reform Act 2019" (PDF). Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ Keown, John (2002). Abortion, doctors and the law : some aspects of the legal regulation of abortion in England from 1803 to 1982. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521894135.

- ↑ Szreter; Fisher

- ↑ "Child Destruction Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Lords. 12 July 1928. col. 998–1000.

- 1 2 C v S [1988] QB 135, [1987] 2 WLR 1108, [1987] 1 All ER 1230, [1987] 2 FLR 505, (1987) 17 Fam Law 269, Court of Appeal (Civil Division)

- ↑ United Kingdom. Court of Appeal (1987). "C. v. S., 25 February 1987". Annual Review of Population Law. 14: 41. PMID 12346721.

- ↑ "Baby destruction woman sentenced". BBC News. 24 May 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ R v Bourne [1939] 1 KB 687, [1938] 3 All ER 615, Court of Criminal Appeal

- ↑ "Our work". spuc.org.uk. Society for the Protection of Unborn Children.

- ↑ House of Commons, Science and Technology Committee. "Scientific Developments Relating to the Abortion Act 1967 Volume 1 Twelfth Report of Session 2006–07". Pdf.

- ↑ "Abortion (Amendment) Bill (Select Committee)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. 26 February 1975. col. 503–542.

- ↑ "Abortion (Amendment) Bill (Select Committee)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. 9 February 1976. col. 100–170.

- ↑ "Abortion (Amendment) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. 13 July 1979. col. 891–983.

- ↑ "Abortion (Amendment) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. 22 January 1988. col. 1228–1296.

- ↑ "Clause 34: Amendment of law relating to termination of pregnancy". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. 21 June 1990. col. 1178–1209.

- ↑ Birchard, Karen (2000). "Northern Ireland resists extending abortion Act". The Lancet. 356 (9223): 52. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)73390-0. S2CID 54407089.

- ↑ "Last chance – Abortion Rights protest tonight". The F-Word. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "Abortion Rights". Abortion Rights. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ Penny, Laurie. "Stand up for the Pro-Choice Majority!". Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill [Lords] (Programme) (No. 2)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "MPs reject cut in abortion limit". BBC News. 21 May 2008.

- ↑ Abbott, Diane (23 July 2008). "Diane Abbott: A right to choose? Not in Northern Ireland". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "MPs pushing abortion rights in NI". 23 July 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ Commons, Table Office, House of. "House of Commons Amendments". publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "Harriet Harman shouldn't be blogging on International Women's Day – she's suppressed women's rights for 12 years". LabourList. 9 March 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "Manifesto". The Labour Party. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "Labour would change the law to stop women in Northern Ireland being sent to prison for abortions". The Independent. 11 May 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ Elgot, Jessica (23 October 2017). "Northern Irish women offered free abortion services in England". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "Abortion statistics for England and Wales 2020, 4.7 Statutory grounds for abortion". www.gov.uk. Department of Health and Social Care. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Termination of Pregnancy Statistics 2019/20". www.health-ni.gov.uk. Department of Health. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ Smyth, Catherine (22 January 2020). "NI abortion: Eight abortions in NI hospitals during 2018–19". BBC News. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ↑ "Abortion statistics 2020: data tables, Table 12g". www.gov.uk. Department of Health and Social Care.

- ↑ "Abortion statistics 2020: data tables, Table 12e". www.gov.uk. Department of Health and Social Care.

- ↑ "Termination of pregnancy statistics year ending December 2020" (PDF). 25 May 2021. p. 18. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ "Table A4: Police recorded crime by offence, Crime in England and Wales". www.ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ "Child Abuse (non-sexual) - prosecution guidance". www.cps.gov.uk. Crown Prosecution Service. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ "So-Called Honour-Based Abuse and Forced Marriage: Guidance on Identifying and Flagging cases". www.cps.gov.uk. Crown Prosecution Service. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 Rowlands S (October 2007). "Contraception and abortion". J R Soc Med. 100 (10): 465–8. doi:10.1258/jrsm.100.10.465. PMC 1997258. PMID 17911129.

- ↑ Royal Commission on the National Health Service (Chapter 18: The NHS and Private Practice). HMSO. 17 July 1979. ISBN 9780101761505. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2006. Government Statistical Service for the Department of Health. 19 June 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- 1 2 Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2004 (PDF). Government Statistical Service for the Department of Health. 27 July 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2008.

- ↑ Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2009. Government Statistical Service for the Department of Health. 25 May 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ↑ Edwin Poots, Minister of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (6 June 2011). "AQW 203/11-15". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Northern Ireland: Northern Ireland Executive. Pdf pp. WA 351.

- ↑ Nakatudde, Nambassa (6 October 2014). Statistics on Abortion (Commons Briefing papers SN04418). House of Commons Library. Pdf.

- ↑ "300 to 400 Maltese women go abroad for an abortion each year". The Malta Independent.

- ↑ "Abortion Statistics, England and Wales: 2018" (PDF).

- ↑ "Q&A: Abortion law". BBC News. 21 June 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ "YouGov/Daily Telegraph Survey Results" (PDF). yougov.com. YouGov. 30 July 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ↑ "Public Attitudes towards Abortion". ipsos.com. Ipsos MORI. 5 September 2011. Pdf of data.

- ↑ Dyer, C. (2011). "Ruling prevents women taking second abortion pill at home". BMJ. 342: d1045. doi:10.1136/bmj.d1045. PMID 21321014. S2CID 37286809.

- ↑ "Government confirms plans to approve the home-use of early abortion pills". GOV.UK.

External links

- UK National Statistics Office Abortion Data (England and Wales)

- Scottish Health Statistics Abortion Data (Scotland)

- "Q&A: Abortion in NI". BBC News. 13 June 2001.

- "Written Answers: Abortion". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. 19 July 2010. col. WA153.