Acritarch

| Acritarchs Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

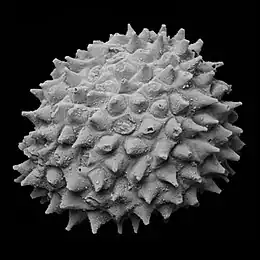

| A supposed Ediacaran embryo contained within an acritarch from the Doushantuo formation | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | incertae sedis |

| (unranked): | Acritarcha Evitt, 1963 |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Acritarchs are organic microfossils, known from approximately 1800 million years ago to the present. The classification is a catch all term used to refer to any organic microfossils that cannot be assigned to other groups. Their diversity reflects major ecological events such as the appearance of predation and the Cambrian explosion.

Definition

Acritarchs were originally defined as non-acid soluble (i.e. non-carbonate, non-siliceous) organic-walled microfossils consisting of a central cavity, and whose biological affinities cannot be determined with certainty.[2][3][4] Most commonly they are composed of thermally altered acid insoluble carbon compounds (kerogen).

Acritarchs may include the remains of a wide range of quite different kinds of organisms—ranging from the egg cases of small metazoans to resting cysts of many kinds of chlorophyta (green algae). It is likely that most acritarch species from the Paleozoic represent various stages of the life cycle of algae that were ancestral to the dinoflagellates.[5] The nature of the organisms associated with older acritarchs is generally not well understood, though many are probably related to unicellular marine algae. In theory, when the biological source (taxon) of an acritarch does become known, that particular microfossil is removed from the acritarchs and classified with its proper group.

While the classification of acritarchs into form genera is entirely artificial, it is not without merit, as the form taxa show traits similar to those of genuine taxa—for example an 'explosion' in the Cambrian and a mass extinction at the end of the Permian.

Classification

Acritarchs were most likely eukaryotes. While archaea and bacteria (prokaryotes) usually produce simple fossils of a very small size, eukaryotic unicellular fossils are usually larger and more complex, with external morphological projections and ornamentation such as spines and hairs that only eukaryotes can produce; as most acritarchs have external projections (e.g., hair, spines, thick cell membranes, etc.), they are predominantly eukaryotes, although simple eukaryote acritarchs also exist.[6]

The recent application of atomic force microscopy, confocal microscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and other sophisticated analytic techniques to the study of the ultrastructure, life history, and systematic affinities of mineralized, but originally organic-walled microfossils,[7][8][9][10][11] has shown that some acritarchs are actually fossilized microalgae. In the end, it may well be, as Moczydłowska et al. suggested in 2011, that many acritarchs will, in fact, turn out to be algae.[12][13]

Occurrence

Acritarchs are found in sedimentary rocks from the present back into the Archean.[14] They are typically isolated from siliciclastic sedimentary rocks using hydrofluoric acid but are occasionally extracted from carbonate-rich rocks. They are excellent candidates for index fossils used for dating rock formations in the Paleozoic Era and when other fossils are not available. Because most acritarchs are thought to be marine (pre-Triassic), they are also useful for palaeoenvironmental interpretation.

The Archean and earliest Proterozoic microfossils termed "acritarchs" may actually be prokaryotes. The earliest eukaryotic acritarchs known (as of 2020) are from between 1950 and 2150 million years ago.[15]

Diversity

At about 1 billion years ago the organisms responsible for acritarchs started to increase in abundance, diversity, size, complexity of shape and especially size and number of spines. Their populations crashed during periods of extensive worldwide glaciations that covered the majority of the planet, but they proliferated in the Cambrian explosion and reached their highest diversity in the Paleozoic. The increased spininess 1000 million years ago possibly resulted from the need for defense against predators, especially predators large enough to swallow them or tear them apart. Other groups of small organisms from the Neoproterozoic era also show signs of anti-predator defenses.[16]

Further evidence that acritarchs were subject to herbivory around this time comes from a consideration of taxon longevity. The abundance of planktonic organisms that evolved between 1,700 and 1,400 million years ago was limited by nutrient availability – a situation which limits the origination of new species because the existing organisms are so specialised to their niches, and no other niches are available for occupation. Approximately 1,000 million years ago, species longevity fell sharply, suggesting that predation pressure, probably by protist herbivores, became an important factor. Predation would have kept populations in check, meaning that some nutrients were left unused, and new niches were available for new species to occupy.[17]

Etymology

Acritarch was coined in 1963 from the Greek ákritos meaning confused (a kritēs, without critic) and archē meaning origin (confer archaic).[18]

Genera

This is a list of genera according to Fossilid.info.[19]

- Acanthodiacrodium (Ordovician)

- Acrosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Actipillion (Ordovician)

- Akomachra (Ordovician)

- Ammonidium (Silurian)

- Aranidium (Cambrian)

- Arbusculidium (Cambrian-Ordovician)

- Archaeodiscina (Cambrian)

- Arcosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Aremoricanium (Ordovician)

- Arkonia (Ordovician)

- Asteridium (Cambrian)

- Athabascaella (Tremadocian, Early Ordovician)

- Axisphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Bacisphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Baltisphaeridium (Cambrian-Silurian)

- Buedingiisphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Caldariola (Cambrian)

- Calyxiella

- Celtiberium

- Cephalonyx

- Ceratophyton (Cambrian)

- Cheleutochroa (Ordovician)

- Chlamydosphaeridia (Ordovician)

- Comasphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Coronitesta (Ordovician)

- Coryphidium (Ordovician)

- Costatilobus (Ordovician)

- Cristallinium (Cambrian)

- Cycloposphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Cymatiogalea (Cambrian)

- Cymatiosphaera (Cambrian-Ordovician)

- Dactylofusa (Ordovician)

- Dasydiacrodium (Cambrian)

- Dicommopalla (Ordovician)

- Dictyosphaera (Paleozoic)

- Dictyosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Diexallophasis (Silurian)

- Dilatisphaera (Ordovician)

- Domasia (Ordovician-Silurian)

- Dongyesphaera (Paleozoic)

- Elektroriskos (Cambrian)

- Elenia

- Eliasum

- Estiastra (Ordovician)

- Excultibrachium (Ordovician)

- Fimbriaglomerella

- Florisphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Globosphaeridium (Cambrian)

- Goniosphaeridium (Cambrian-Ordovician)

- Gorgonisphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Granomarginata (Cambrian)

- Gyalorhethium (Ordovician)

- Hapsidopalla (Ordovician)

- Helosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Impluviculus (Cambrian)

- Introvertocystis (Late Cretaceous)

- Izhoria

- Joehvisphaera (Ordovician)

- Korilophyton (Cambrian)

- Kundasphaera (Ordovician)

- Labyrinthosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Lacunosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Ladogella

- Leiofusa (Cambrian-Silurian)

- Leiosphaeridia (Cambrian-Silurian)

- Leiovalia (Ordovician)

- Liepaina (Cambrian)

- Liliosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Lophosphaeridium (Ordovician-Silurian)

- Lunulidia

- Micrhystridium (Ordovician-Silurian)

- Multiplicisphaeridium (Cambiran-Silurian)

- Nanocyclopia (Ordovician)

- Nodosus

- Oppilatala (Silurian)

- Ordovicidium (Ordovician)

- Orthosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Ovulum (Cambrian)

- Palaeocladophora (Cambrian)

- Palaeomonostroma (Cambrian)

- Peteinosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Pheoclosterium (Ordovician)

- Pirea (Cambrian)

- Poikilofusa

- Polyancistrodorus (Ordovician)

- Polyedryxium (Ordovician)

- Polygonium (Cambrian-Ordovician)

- Portalites (Permian)

- Priscogaleata (Ordovician)

- Priscotheca

- Protosphaeridium (Silurian)

- Pterospermella

- Pterospermopsis (Ordovician)

- Pulvinosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Quadrisporites (Permian)

- Raplasphaera (Ordovician)

- Revinotesta (Ordovician)

- Rhopaliophora (Ordovician)

- Saharidia (Ordovician)

- Salopidium (Silurian)

- Satka (Paleozoic)

- Skiagia (Cambrian)

- Solisphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Stellechinatum (Ordovician)

- Stelliferidium (Cambrian)

- Taeniosphaeridium (Ordovician)

- Tasmanites (Ordovician-Silurian)

- Tetraporina (Permian)

- Timofeevia (Cambrian-Ordovician)

- Tranvikium (Ordovician)

- Trichosphaeridium

- Tunisphaeridium (Ordovician-Silurian)

- Tylotopalla (Ordovician)

- Vernanimalcula (Pre-Cambrian)

- Veryhachium (Cambrian-Silurian)

- Villosacapsula (Ordovician)

- Visbysphaera (Silurian)

- Volkovia

- Vulcanisphaera (Cambrian-Ordovician)

- Winwaloeusia (Ordovician)

See also

References

- ↑ Cunningham, John A.; Vargas, Kelly; Yin, Zongjun; Bengtson, Stefan; Donoghue, Philip C. J. (2017). "The Weng'an Biota (Doushantuo Formation): An Ediacaran window on soft-bodied and multicellular microorganisms". Journal of the Geological Society. 174 (5): 793–802. Bibcode:2017JGSoc.174..793C. doi:10.1144/jgs2016-142.

- ↑ Evitt, William R. (1963). "A discussion and proposals concerning fossil dinoflagellates, hystrichospheres, and acritarchs, II" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 49 (3): 298–302. Bibcode:1963PNAS...49..298E. doi:10.1073/pnas.49.3.298. PMC 299818. PMID 16591055 – via PNAS.

- ↑ Martin, Francine (1993). "Acritarchsa Review". Biological Reviews. 68 (4): 475–537. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1993.tb01241.x. S2CID 221527533.

- ↑ Colbath, G.Kent; Grenfell, Hugh R. (1995). "Review of biological affinities of Paleozoic acid-resistant, organic-walled eukaryotic algal microfossils (Including "acritarchs")". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 86 (3–4): 287–314. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(94)00148-D.

- ↑ Colbath, G.Kent; Grenfell, Hugh R. (1995). "Review of biological affinities of Paleozoic acid-resistant, organic-walled eukaryotic algal microfossils (including "acritarchs")". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 86 (3–4): 287–314. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(94)00148-d. ISSN 0034-6667.

- ↑ Buick, R. . (2010). "Early life: Ancient acritarchs". Nature. 463 (7283): 885–886. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..885B. doi:10.1038/463885a. PMID 20164911.

- ↑ Kempe, A.; Schopf, J. W.; Altermann, W.; Kudryavtsev, A. B.; Heckl, W. M. (2002). "Atomic force microscopy of Precambrian microscopic fossils". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (14): 9117–9120. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.9117K. doi:10.1073/pnas.142310299. PMC 123103. PMID 12089337.

- ↑ Kempe, A.; Wirth, R.; Altermann, W.; Stark, R.; Schopf, J.; Heckl, W. (2005). "Focussed ion beam preparation and in situ nanoscopic study of Precambrian acritarchs". Precambrian Research. 140 (1–2): 36–54. Bibcode:2005PreR..140...36K. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2005.07.002.

- ↑ Marshall, C.; Javaux, E.; Knoll, A.; Walter, M. (2005). "Combined micro-Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and micro-Raman spectroscopy of Proterozoic acritarchs: A new approach to Palaeobiology". Precambrian Research. 138 (3–4): 208–224. Bibcode:2005PreR..138..208M. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2005.05.006.

- ↑ Kaźmierczak, Józef; Kremer, Barbara (2009). "Spore-Like Bodies in Some Early Paleozoic Acritarchs: Clues to Chlorococcalean Affinities". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 54 (3): 541–551. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0060.

- ↑ Schopf, J. William; Kudryavtsev, Anatoliy B.; Sergeev, Vladimir N. (2010). "Confocal laser scanning microscopy and Raman imagery of the late Neoproterozoic Chichkan microbiota of South Kazakhstan". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (3): 402–416. doi:10.1666/09-134.1. S2CID 130041483.

- ↑ Moczydłowska, Małgorzata; Landing, ED; Zang, Wenlong; Palacios, Teodoro (2011). "Proterozoic phytoplankton and timing of Chlorophyte algae origins". Palaeontology. 54 (4): 721–733. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01054.x.

- ↑ Chamberlain, John; Chamberlain, Rebecca; Brown, James (2016). "A Mineralized Alga and Acritarch Dominated Microbiota from the Tully Formation (Givetian) of Pennsylvania, USA". Geosciences. 6 (4): 57. Bibcode:2016Geosc...6...57C. doi:10.3390/geosciences6040057.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - ↑ "MONTENARI, M. & LEPPIG, U. (2003): The Acritarcha: their classification morphology, ultrastructure and palaeoecological/palaeogeographical distribution". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 77: 173–194. 2003. doi:10.1007/bf03004567. S2CID 127238427.

- ↑ Yin, Leiming (February 2020). "Microfossils from the Paleoproterozoic Hutuo Group, Shanxi, North China: Early evidence for eukaryotic metabolism". Precambrian Research. 342: 105650. Bibcode:2020PreR..342j5650Y. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2020.105650.

- ↑ Bengtson, S. (2002). "Origins and early evolution of predation" (PDF). In Kowalewski, M.; Kelley, P.H. (eds.). The fossil record of predation. The Paleontological Society Papers. Vol. 8. The Paleontological Society. pp. 289–317. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ↑ Stanley, S. M. (2008). "Predation defeats competition on the seafloor". Paleobiology. 34: 1–21. doi:10.1666/07026.1. S2CID 83713101.

- ↑ definition of acritarch at dictionary.com

- ↑ "Actipillion".

External links

- CIMP Subcommission on Acritarchs* "CIMP Home page". Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Commission Internationale de Microflore du Paléozoique (CIMP), international commission for Palaeozoic palynology.

- "The Micropalaeontological Society". Archived from the original on 8 December 2004. Retrieved 12 November 2004.

- "The Palynological Society". The American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists (AASP)