Agent Orange

| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

|

Agent Orange is a herbicide and defoliant chemical, one of the "tactical use" Rainbow Herbicides. It is widely known for its use by the U.S. military as part of its herbicidal warfare program, Operation Ranch Hand,[1] during the Vietnam War from 1961 to 1971.[2] It is a mixture of equal parts of two herbicides, 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D. In addition to its damaging environmental effects, traces of dioxin (mainly TCDD, the most toxic of its type)[3] found in the mixture have caused major health problems for many individuals who were exposed, and their offspring.

Agent Orange was produced in the United States from the late 1940s and was used in industrial agriculture and was also sprayed along railroads and power lines to control undergrowth in forests. During the Vietnam War the U.S military procured over 20 million gallons consisting of a fifty-fifty mixture of 2,4-D and Dioxin-contaminated 2,4,5-T. Nine chemical companies produced it: Dow Chemical Company, Monsanto Company, Diamond Shamrock Corporation, Hercules Inc., Thompson Hayward Chemical Co., United States Rubber Company (Uniroyal), Thompson Chemical Co., Hoffman-Taff Chemicals, Inc., and Agriselect.[4]

The government of Vietnam says that up to four million people in Vietnam were exposed to the defoliant, and as many as three million people have suffered illness because of Agent Orange,[5] while the Red Cross of Vietnam estimates that up to one million people were disabled or have health problems as a result of exposure to Agent Orange.[6] The United States government has described these figures as unreliable,[7] while documenting cases of leukemia, Hodgkin's lymphoma, and various kinds of cancer in exposed US military veterans. An epidemiological study done by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that there was an increase in the rate of birth defects of the children of military personnel as a result of Agent Orange.[8][9] Agent Orange has also caused enormous environmental damage in Vietnam. Over 3,100,000 hectares (31,000 km2 or 11,969 mi2) of forest were defoliated. Defoliants eroded tree cover and seedling forest stock, making reforestation difficult in numerous areas. Animal species diversity sharply reduced in contrast with unsprayed areas.[10][11]

The use of Agent Orange in Vietnam resulted in numerous legal actions. The United Nations ratified United Nations General Assembly Resolution 31/72 and the Environmental Modification Convention. Lawsuits filed on behalf of both U.S. and Vietnamese veterans sought compensation for damages.

Agent Orange was first used by the British Armed Forces in Malaya during the Malayan Emergency. It was also used by the U.S. military in Laos and Cambodia during the Vietnam War because forests near the border with Vietnam were used by the Viet Cong. The herbicide was more recently used in Brazil to clear out sections of the Amazon rainforest for agriculture.[12]

Chemical composition

The active ingredient of Agent Orange was an equal mixture of two phenoxy herbicides – 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T) – in iso-octyl ester form, which contained traces of the dioxin 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD).[13] TCDD was a trace (typically 2-3 ppm, ranging from 50 ppb to 50 ppm)[14] - but significant - contaminant of Agent Orange.

Toxicology

TCDD is the most toxic of the dioxins and is classified as a human carcinogen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[15] The fat-soluble nature of TCDD causes it to readily enter the body through physical contact or ingestion.[16] Dioxin easily accumulates in the food chain. Dioxin enters the body by attaching to a protein called the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a transcription factor. When TCDD binds to AhR, the protein moves to the nucleus, where it influences gene expression.[17][18]

According to U.S. government reports, if not bound chemically to a biological surface such as soil, leaves or grass, Agent Orange dries quickly after spraying and breaks down within hours to days when exposed to sunlight and is no longer harmful.[19]

Development

Several herbicides were developed as part of efforts by the United States and the United Kingdom to create herbicidal weapons for use during World War II. These included 2,4-D, 2,4,5-T, MCPA (2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid, 1414B and 1414A, recoded LN-8 and LN-32), and isopropyl phenylcarbamate (1313, recoded LN-33).[20]

In 1943, the United States Department of the Army contracted botanist and bioethicist Arthur Galston, who discovered the defoliants later used in Agent Orange, and his employer University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign to study the effects of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T on cereal grains (including rice) and broadleaf crops.[21] While a graduate and post-graduate student at the University of Illinois, Galston's research and dissertation focused on finding a chemical means to make soybeans flower and fruit earlier.[22] He discovered both that 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) would speed up the flowering of soybeans and that in higher concentrations it would defoliate the soybeans.[22] From these studies arose the concept of using aerial applications of herbicides to destroy enemy crops to disrupt their food supply. In early 1945, the U.S. Army ran tests of various 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T mixtures at the Bushnell Army Airfield in Florida. As a result, the U.S. began a full-scale production of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T and would have used it against Japan in 1946 during Operation Downfall if the war had continued.[23][24]

In the years after the war, the U.S. tested 1,100 compounds, and field trials of the more promising ones were done at British stations in India and Australia, in order to establish their effects in tropical conditions, as well as at the U.S.'s testing ground in Florida.[20] Between 1950 and 1952, trials were conducted in Tanganyika, at Kikore and Stunyansa, to test arboricides and defoliants under tropical conditions. The chemicals involved were 2,4-D, 2,4,5-T, and endothall (3,6-endoxohexahydrophthalic acid). During 1952–53, the unit supervised the aerial spraying of 2,4,5-T in Kenya to assess the value of defoliants in the eradication of tsetse fly.[20]

Early use

In Malaya the local unit of Imperial Chemical Industries researched defoliants as weed killers for rubber plantations. Roadside ambushes by the Malayan National Liberation Army were a danger to the British military during the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) so trials were made to defoliate vegetation that might hide ambush sites, but hand removal was found cheaper. A detailed account of how the British experimented with the spraying of herbicides was written by two scientists, E.K. Woodford of Agricultural Research Council's Unit of Experimental Agronomy and H.G.H. Kearns of the University of Bristol.[25]

After the Malayan Emergency ended in 1960, the U.S. considered the British precedent in deciding that the use of defoliants was a legal tactic of warfare. Secretary of State Dean Rusk advised President John F. Kennedy that the British had established a precedent for warfare with herbicides in Malaya.[26][27]

Use in the Vietnam War

In mid-1961, President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam asked the United States to help defoliate the lush jungle that was providing cover to his Communist enemies[28].[29] In August of that year, the Republic of Vietnam Air Force conducted herbicide operations with American help. Diem's request launched a policy debate in the White House and the State and Defense Departments. Many U.S. officials supporting herbicide operations, pointing out that the British had already used herbicides and defoliants in Malaya during the 1950's. In November 1961, Kennedy authorized the start of Operation Ranch Hand, the codename for the United States Air Force's herbicide program in Vietnam. The herbicide operations were formally directed by the government of South Vietnam.[30]

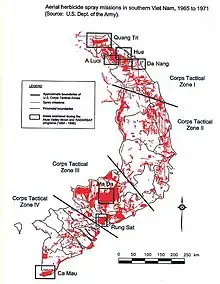

During the Vietnam War, between 1962 and 1971, the United States military sprayed nearly 20,000,000 U.S. gallons (76,000 m3) of various chemicals – the "rainbow herbicides" and defoliants – in Vietnam, eastern Laos, and parts of Cambodia as part of Operation Ranch Hand, reaching its peak from 1967 to 1969. For comparison purposes, an olympic size pool holds approximately 660,000 U.S. gal (2,500 m3).[31][32][26] As the British did in Malaya, the goal of the U.S. was to defoliate rural/forested land, depriving guerrillas of food and concealment and clearing sensitive areas such as around base perimeters and possible ambush sites along roads and canals.[33][30] Samuel P. Huntington argued that the program was also a part of a policy of forced draft urbanization, which aimed to destroy the ability of peasants to support themselves in the countryside, forcing them to flee to the U.S.-dominated cities, depriving the guerrillas of their rural support base. [34]

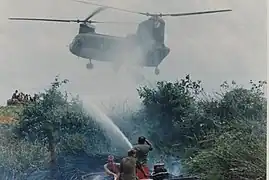

Agent Orange was usually sprayed from helicopters or from low-flying C-123 Provider aircraft, fitted with sprayers and "MC-1 Hourglass" pump systems and 1,000 U.S. gallons (3,800 L) chemical tanks. Spray runs were also conducted from trucks, boats, and backpack sprayers.[35][3][36] Altogether, over 80 million litres of Agent Orange were applied.[37]

The first batch of herbicides was unloaded at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in South Vietnam, on January 9, 1962.[38] U.S. Air Force records show at least 6,542 spraying missions took place over the course of Operation Ranch Hand.[39] By 1971, 12 percent of the total area of South Vietnam had been sprayed with defoliating chemicals, at an average concentration of 13 times the recommended U.S. Department of Agriculture application rate for domestic use.[40] In South Vietnam alone, an estimated 39,000 square miles (10,000,000 ha) of agricultural land was ultimately destroyed.[41] In some areas, TCDD concentrations in soil and water were hundreds of times greater than the levels considered safe by the EPA.[42][43]

The campaign destroyed 20,000 square kilometres (5×106 acres) of upland and mangrove forests and thousands of square kilometres of crops.[44] Overall, more than 20% of South Vietnam's forests were sprayed at least once over the nine-year period.[45][46] 3.2% of South Vietnam’s cultivated land was sprayed at least once between 1965 and 1971. 90% of herbicide use was directed at defoliation.[30]

The U.S. military began targeting food crops in October 1962, primarily using Agent Blue; the American public was not made aware of the crop destruction programs until 1965 (and it was then believed that crop spraying had begun that spring). In 1965, 42% of all herbicide spraying was dedicated to food crops. In 1965, members of the U.S. Congress were told, "crop destruction is understood to be the more important purpose ... but the emphasis is usually given to the jungle defoliation in public mention of the program." The first official acknowledgment of the programs came from the State Department in March 1966.[45][47]

When crops were destroyed, the Viet Cong would compensate for the loss of food by confiscating more food from local villages.[30] Some military personnel reported being told they were destroying crops used to feed guerrillas, only to later discover, most of the destroyed food was actually produced to support the local civilian population. For example, according to Wil Verwey, 85% of the crop lands in Quang Ngai province were scheduled to be destroyed in 1970 alone. He estimated this would have caused famine and left hundreds of thousands of people without food or malnourished in the province.[48] According to a report by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the herbicide campaign had disrupted the food supply of more than 600,000 people by 1970. [49]

Many experts at the time, including Arthur Galston, opposed herbicidal warfare because of concerns about the side effects to humans and the environment by indiscriminately spraying the chemical over a wide area. As early as 1966, resolutions were introduced to the United Nations charging that the U.S. was violating the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which regulated the use of chemical and biological weapons. The U.S. defeated most of the resolutions,[50][51] arguing that Agent Orange was not a chemical or a biological weapon as it was considered a herbicide and a defoliant and it was used in effort to destroy plant crops and to deprive the enemy of concealment and not meant to target human beings. The U.S. delegation argued that a weapon, by definition, is any device used to injure, defeat, or destroy living beings, structures, or systems, and Agent Orange did not qualify under that definition. It also argued that if the U.S. were to be charged for using Agent Orange, then the United Kingdom and its Commonwealth nations should be charged since they also used it widely during the Malayan Emergency in the 1950s.[52] In 1969, the United Kingdom commented on the draft Resolution 2603 (XXIV): "The evidence seems to us to be notably inadequate for the assertion that the use in war of chemical substances specifically toxic to plants is prohibited by international law."[53]

A study carried out by the Bionetic Research Laboratories between 1965 and 1968 found malformations in test animals caused by 2,4,5-T, a component of Agent Orange. The study was later brought to the attention of the White House in October 1969. Other studies reported similar results and the Department of Defense began to reduce the herbicide operation. On April 15, 1970, it was announced that the use of Agent Orange was suspended. Two brigades of the Americal Division in the summer of 1970 continued to use Agent Orange for crop destruction in violation of the suspension. An investigation led to disciplinary action against the brigade and division commanders because they had falsified reports to hide its use. Defoliation and crop destruction were completely stopped by June 30, 1971.[30]

- Gallery

Stacks of 200 L (55 gallon) drums containing Agent Orange.

Stacks of 200 L (55 gallon) drums containing Agent Orange. Defoliant spray run, part of Operation Ranch Hand, during the Vietnam War by UC-123B Provider aircraft.

Defoliant spray run, part of Operation Ranch Hand, during the Vietnam War by UC-123B Provider aircraft. U.S. Army armored personnel carrier (APC) spraying Agent Orange over Vietnamese rice fields during the Vietnam War.

U.S. Army armored personnel carrier (APC) spraying Agent Orange over Vietnamese rice fields during the Vietnam War. A UH-1D helicopter from the 336th Aviation Company sprays a defoliation agent over farmland in the Mekong Delta.

A UH-1D helicopter from the 336th Aviation Company sprays a defoliation agent over farmland in the Mekong Delta. U.S. Army Operations In Vietnam: River bank defoliation

U.S. Army Operations In Vietnam: River bank defoliation A U.S. Air Force Fairchild C-123 Provider aircraft crop-dusting in Vietnam during Operation Ranch Hand.

A U.S. Air Force Fairchild C-123 Provider aircraft crop-dusting in Vietnam during Operation Ranch Hand. A Fairchild C-123 Provider aircraft spraying defoliant in South Vietnam in 1962.

A Fairchild C-123 Provider aircraft spraying defoliant in South Vietnam in 1962. Ranch Hand UC-123 clearing a roadside in central South Vietnam in 1966.

Ranch Hand UC-123 clearing a roadside in central South Vietnam in 1966. U.S. Air Force aircraft spraying defoliant

U.S. Air Force aircraft spraying defoliant Spraying Agent Orange in Mekong Delta near Can Tho, 1969

Spraying Agent Orange in Mekong Delta near Can Tho, 1969

Health effects

There are various types of cancer associated with Agent Orange, including chronic B-cell leukemia, Hodgkin's lymphoma, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, prostate cancer, respiratory cancer, lung cancer, and soft tissue sarcomas.[54]

Vietnamese people

The government of Vietnam states that 4 million of its citizens were exposed to Agent Orange, and as many as 3 million have suffered illnesses because of it; these figures include their children who were exposed.[5] The Red Cross of Vietnam estimates that up to 1 million people are disabled or have health problems due to contaminated Agent Orange.[6] The United States government has challenged these figures as being unreliable.[7]

According to a study by Dr. Nguyen Viet Nhan, children in the areas where Agent Orange was used have been affected and have multiple health problems, including cleft palate, mental disabilities, hernias, and extra fingers and toes.[55][56] In the 1970s, high levels of dioxin were found in the breast milk of South Vietnamese women, and in the blood of U.S. military personnel who had served in Vietnam.[57] The most affected zones are the mountainous area along Truong Son (Long Mountains) and the border between Vietnam and Cambodia. The affected residents are living in substandard conditions with many genetic diseases.[58][59]

In 2006, Anh Duc Ngo and colleagues of the University of Texas Health Science Center published a meta-analysis that exposed a large amount of heterogeneity (different findings) between studies, a finding consistent with a lack of consensus on the issue.[60] Despite this, statistical analysis of the studies they examined resulted in data that the increase in birth defects/relative risk (RR) from exposure to agent orange/dioxin "appears" to be on the order of 3 in Vietnamese-funded studies, but 1.29 in the rest of the world. There is data near the threshold of statistical significance suggesting Agent Orange contributes to still-births, cleft palate, and neural tube defects, with spina bifida being the most statistically significant defect.[17] The large discrepancy in RR between Vietnamese studies and those in the rest of the world has been ascribed to bias in the Vietnamese studies.[60]

Twenty-eight of the former U.S. military bases in Vietnam where the herbicides were stored and loaded onto airplanes may still have high levels of dioxins in the soil, posing a health threat to the surrounding communities. Extensive testing for dioxin contamination has been conducted at the former U.S. airbases in Da Nang, Phù Cát District and Biên Hòa. Some of the soil and sediment on the bases have extremely high levels of dioxin requiring remediation. The Da Nang Air Base has dioxin contamination up to 350 times higher than international recommendations for action.[61][62] The contaminated soil and sediment continue to affect the citizens of Vietnam, poisoning their food chain and causing illnesses, serious skin diseases and a variety of cancers in the lungs, larynx, and prostate.[55]

.jpg.webp) A person with birth deformities associated with prenatal exposure to Agent Orange

A person with birth deformities associated with prenatal exposure to Agent Orange Major Tự Đức Phang was exposed to dioxin-contaminated Agent Orange.

Major Tự Đức Phang was exposed to dioxin-contaminated Agent Orange. A group of handicapped children in Ho Chi Minh, some of them affected by Agent Orange

A group of handicapped children in Ho Chi Minh, some of them affected by Agent Orange Kan Lay, 55 years old, and her son, Ke Van Bec, 14 years old, A Luoi Valley, Vietnam, December 2004.

Kan Lay, 55 years old, and her son, Ke Van Bec, 14 years old, A Luoi Valley, Vietnam, December 2004.

U.S. veterans

While in Vietnam, the veterans were told not to worry and were persuaded the chemical was harmless.[63] After returning home, Vietnam veterans began to suspect their ill health or the instances of their wives having miscarriages or children born with birth defects might be related to Agent Orange and the other toxic herbicides to which they had been exposed in Vietnam. Veterans began to file claims in 1977 to the Department of Veterans Affairs for disability payments for health care for conditions they believed were associated with exposure to Agent Orange, or more specifically, dioxin, but their claims were denied unless they could prove the condition began when they were in the service or within one year of their discharge.[64] In order to qualify for compensation, veterans must have served on or near the perimeters of military bases in Thailand during the Vietnam Era, where herbicides were tested and stored outside of Vietnam, veterans who were crew members on C-123 planes flown after the Vietnam War, or were associated with Department of Defense (DoD) projects to test, dispose of, or store herbicides in the U.S.[65]

By April 1993, the Department of Veterans Affairs had compensated only 486 victims, although it had received disability claims from 39,419 soldiers who had been exposed to Agent Orange while serving in Vietnam.[66]

In a November 2004 Zogby International poll of 987 people, 79% of respondents thought the U.S. chemical companies which produced Agent Orange defoliant should compensate U.S. soldiers who were affected by the toxic chemical used during the war in Vietnam. Also, 51% said they supported compensation for Vietnamese Agent Orange victims.[67]

National Academy of Medicine

Starting in the early 1990s, the federal government directed the Institute of Medicine (IOM), now known as the National Academy of Medicine, to issue reports every 2 years on the health effects of Agent Orange and similar herbicides. First published in 1994 and titled Veterans and Agent Orange, the IOM reports assess the risk of both cancer and non-cancer health effects. Each health effect is categorized by evidence of association based on available research data.[3] The last update was published in 2016, entitled "Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2014."

The report shows sufficient evidence of an association with soft tissue sarcoma; non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL); Hodgkin disease; Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL); including hairy cell leukemia and other chronic B-cell leukemias. Limited or suggested evidence of an association was linked with respiratory cancers (lung, bronchus, trachea, larynx); prostate cancer; multiple myeloma; and bladder cancer. Numerous other cancers were determined to have inadequate or insufficient evidence of links to Agent Orange.

The National Academy of Medicine has repeatedly concluded that any evidence suggestive of an association between Agent Orange and prostate cancer is, "limited because chance, bias, and confounding could not be ruled out with confidence."[68]

At the request of the Veterans Administration, the Institute Of Medicine evaluated whether service in these C-123 aircraft could have plausibly exposed soldiers and been detrimental to their health. Their report "Post-Vietnam Dioxin Exposure in Agent Orange-Contaminated C-123 Aircraft" confirmed it.[69]

U.S. Public Health Service

Publications by the United States Public Health Service have shown that Vietnam veterans, overall, have increased rates of cancer, and nerve, digestive, skin, and respiratory disorders. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that in particular, there are higher rates of acute/chronic leukemia, Hodgkin's lymphoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, throat cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, colon cancer, Ischemic heart disease, soft tissue sarcoma, and liver cancer.[70][71] With the exception of liver cancer, these are the same conditions the U.S. Veterans Administration has determined may be associated with exposure to Agent Orange/dioxin and are on the list of conditions eligible for compensation and treatment.[71][72]

Military personnel who were involved in storage, mixture and transportation (including aircraft mechanics), and actual use of the chemicals were probably among those who received the heaviest exposures.[73] Military members who served on Okinawa also claim to have been exposed to the chemical, but there is no verifiable evidence to corroborate these claims.[74]

Some studies have suggested that veterans exposed to Agent Orange may be more at risk of developing prostate cancer[75] and potentially more than twice as likely to develop higher-grade, more lethal prostate cancers.[76] However, a critical analysis of these studies and 35 others consistently found that there was no significant increase in prostate cancer incidence or mortality in those exposed to Agent Orange or 2,3,7,8-tetracholorodibenzo-p-dioxin.[77]

U.S. Veterans of Laos and Cambodia

The United States fought secret wars in Laos and Cambodia, dropping large quantities of Agent Orange in each of those countries. According to one estimate, the U.S. dropped 475,500 gallons of Agent Orange in Laos and 40,900 in Cambodia.[32][78][79] Because Laos and Cambodia were neutral during the Vietnam War, the U.S. attempted to keep secret its wars, including its bombing campaigns against those countries, from the American population and has largely avoided compensating American veterans and CIA personnel stationed in Cambodia and Laos who suffered permanent injuries as a result of exposure to Agent Orange there.[78][80]

One noteworthy exception, according to the U.S. Department of Labor, is a claim filed with the CIA by an employee of "a self-insured contractor to the CIA that was no longer in business." The CIA advised the Department of Labor that it "had no objections" to paying the claim and Labor accepted the claim for payment:

Civilian Exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam: GAO-05-371 April 2005.Figure 3: Overview of the Workers' Compensation Claims Process for Contract Employees: " ... Of the 20 claims filed by contract employees [of the united States government], 9 were initially denied by the insurance carriers and 1 was approved for payment. ... The claim that was approved by Labor for payment involved a self-insured contractor to the CIA that was no longer in business. Absent an employer or insurance carrier, the CIA--acting in the role of the employer and the insurance carrier--stated that it "had no objections" to paying the claim. Labor reviewed the claim and accepted it for payment."[81]

Ecological impact

About 17.8%—3,100,000 hectares (31,000 km2; 12,000 sq mi)—of the total forested area of Vietnam was sprayed during the war, which disrupted the ecological equilibrium. The persistent nature of dioxins, erosion caused by loss of tree cover, and loss of seedling forest stock meant that reforestation was difficult (or impossible) in many areas.[11] Many defoliated forest areas were quickly invaded by aggressive pioneer species (such as bamboo and cogon grass), making forest regeneration difficult and unlikely. Animal species diversity was also impacted; in one study a Harvard biologist found 24 species of birds and 5 species of mammals in a sprayed forest, while in two adjacent sections of unsprayed forest there were 145 and 170 species of birds and 30 and 55 species of mammals.[82]

Dioxins from Agent Orange have persisted in the Vietnamese environment since the war, settling in the soil and sediment and entering the food chain through animals and fish which feed in the contaminated areas. The movement of dioxins through the food web has resulted in bioconcentration and biomagnification.[10] The areas most heavily contaminated with dioxins are former U.S. air bases.[83]

Sociopolitical impact

American policy during the Vietnam War was to destroy crops, accepting the sociopolitical impact that that would have.[49] The RAND Corporation's Memorandum 5446-ISA/ARPA states: "the fact that the VC [the Vietcong] obtain most of their food from the neutral rural population dictates the destruction of civilian crops ... if they are to be hampered by the crop destruction program, it will be necessary to destroy large portions of the rural economy – probably 50% or more".[84] Crops were deliberately sprayed with Agent Orange and areas were bulldozed clear of vegetation forcing many rural civilians to cities.[49]

Legal and diplomatic proceedings

International

The extensive environmental damage that resulted from usage of the herbicide prompted the United Nations to pass Resolution 31/72 and ratify the Environmental Modification Convention. Many states do not regard this as a complete ban on the use of herbicides and defoliants in warfare, but it does require case-by-case consideration.[85][86] In the Conference on Disarmament, Article 2(4) Protocol III of the weaponry convention contains "The Jungle Exception", which prohibits states from attacking forests or jungles "except if such natural elements are used to cover, conceal or camouflage combatants or military objectives or are military objectives themselves". This exception voids any protection of any military and civilian personnel from a napalm attack or something like Agent Orange and is clear that it was designed to cover situations like U.S. tactics in Vietnam.[87]

Class action lawsuit

Since at least 1978, several lawsuits have been filed against the companies which produced Agent Orange, among them Dow Chemical, Monsanto, and Diamond Shamrock.[88] Attorney Hy Mayerson was an early pioneer in Agent Orange litigation, working with environmental attorney Victor Yannacone in 1980 on the first class-action suits against wartime manufacturers of Agent Orange. In meeting Dr. Ronald A. Codario, one of the first civilian doctors to see affected patients, Mayerson, so impressed by the fact a physician would show so much interest in a Vietnam veteran, forwarded more than a thousand pages of information on Agent Orange and the effects of dioxin on animals and humans to Codario's office the day after he was first contacted by the doctor.[89] The corporate defendants sought to escape culpability by blaming everything on the U.S. government.[90]

In 1980, Mayerson, with Sgt. Charles E. Hartz as their principal client, filed the first U.S. Agent Orange class-action lawsuit in Pennsylvania, for the injuries military personnel in Vietnam suffered through exposure to toxic dioxins in the defoliant.[91] Attorney Mayerson co-wrote the brief that certified the Agent Orange Product Liability action as a class action, the largest ever filed as of its filing.[92] Hartz's deposition was one of the first ever taken in America, and the first for an Agent Orange trial, for the purpose of preserving testimony at trial, as it was understood that Hartz would not live to see the trial because of a brain tumor that began to develop while he was a member of Tiger Force, special forces, and LRRPs in Vietnam.[93] The firm also located and supplied critical research to the veterans' lead expert, Dr. Codario, including about 100 articles from toxicology journals dating back more than a decade, as well as data about where herbicides had been sprayed, what the effects of dioxin had been on animals and humans, and every accident in factories where herbicides were produced or dioxin was a contaminant of some chemical reaction.[89]

The chemical companies involved denied that there was a link between Agent Orange and the veterans' medical problems. However, on May 7, 1984, seven chemical companies settled the class-action suit out of court just hours before jury selection was to begin. The companies agreed to pay $180 million as compensation if the veterans dropped all claims against them.[94] Slightly over 45% of the sum was ordered to be paid by Monsanto alone.[95] Many veterans who were victims of Agent Orange exposure were outraged the case had been settled instead of going to court and felt they had been betrayed by the lawyers. "Fairness Hearings" were held in five major American cities, where veterans and their families discussed their reactions to the settlement and condemned the actions of the lawyers and courts, demanding the case be heard before a jury of their peers. Federal Judge Jack B. Weinstein refused the appeals, claiming the settlement was "fair and just". By 1989, the veterans' fears were confirmed when it was decided how the money from the settlement would be paid out. A totally disabled Vietnam veteran would receive a maximum of $12,000 spread out over the course of 10 years. Furthermore, by accepting the settlement payments, disabled veterans would become ineligible for many state benefits that provided far more monetary support than the settlement, such as food stamps, public assistance, and government pensions. A widow of a Vietnam veteran who died of Agent Orange exposure would receive $3,700.[96]

In 2004, Monsanto spokesman Jill Montgomery said Monsanto should not be liable at all for injuries or deaths caused by Agent Orange, saying: "We are sympathetic with people who believe they have been injured and understand their concern to find the cause, but reliable scientific evidence indicates that Agent Orange is not the cause of serious long-term health effects."[97]

New Jersey Agent Orange Commission

In 1980, New Jersey created the New Jersey Agent Orange Commission, the first state commission created to study its effects. The commission's research project in association with Rutgers University was called "The Pointman Project". It was disbanded by Governor Christine Todd Whitman in 1996.[98] During the first phase of the project, commission researchers devised ways to determine small dioxin levels in blood. Prior to this, such levels could only be found in the adipose (fat) tissue. The project studied dioxin (TCDD) levels in blood as well as in adipose tissue in a small group of Vietnam veterans who had been exposed to Agent Orange and compared them to those of a matched control group; the levels were found to be higher in the former group.[99] The second phase of the project continued to examine and compare dioxin levels in various groups of Vietnam veterans, including Army, Marines and brown water riverboat Navy personnel.[100]

U.S. Congress

In 1991, Congress enacted the Agent Orange Act, giving the Department of Veterans Affairs the authority to declare certain conditions "presumptive" to exposure to Agent Orange/dioxin, making these veterans who served in Vietnam eligible to receive treatment and compensation for these conditions.[101] The same law required the National Academy of Sciences to periodically review the science on dioxin and herbicides used in Vietnam to inform the Secretary of Veterans Affairs about the strength of the scientific evidence showing association between exposure to Agent Orange/dioxin and certain conditions.[102] The authority for the National Academy of Sciences reviews and addition of any new diseases to the presumptive list by the VA is expiring in 2015 under the sunset clause of the Agent Orange Act of 1991.[103] Through this process, the list of 'presumptive' conditions has grown since 1991, and currently the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has listed prostate cancer, respiratory cancers, multiple myeloma, type II diabetes mellitus, Hodgkin's disease, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, chloracne, porphyria cutanea tarda, peripheral neuropathy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and spina bifida in children of veterans exposed to Agent Orange as conditions associated with exposure to the herbicide. This list now includes B cell leukemias, such as hairy cell leukemia, Parkinson's disease and ischemic heart disease, these last three having been added on August 31, 2010. Several highly placed individuals in government are voicing concerns about whether some of the diseases on the list should, in fact, actually have been included.[104]

In 2011, an appraisal of the 20 year long Air Force Health Study that began in 1982 indicates that the results of the AFHS as they pertain to Agent Orange, do not provide evidence of disease in the Operation Ranch Hand veterans caused by "their elevated levels of exposure to Agent Orange".[105]

The VA initially denied the applications of post-Vietnam C-123 aircrew veterans because as veterans without "boots on the ground" service in Vietnam, they were not covered under VA's interpretation of "exposed". In June 2015, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs issued an Interim final rule providing presumptive service connection for post-Vietnam C-123 aircrews, maintenance staff and aeromedical evacuation crews. The VA now provides medical care and disability compensation for the recognized list of Agent Orange illnesses.[106]

U.S.–Vietnamese government negotiations

In 2002, Vietnam and the U.S. held a joint conference on Human Health and Environmental Impacts of Agent Orange. Following the conference, the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) began scientific exchanges between the U.S. and Vietnam, and began discussions for a joint research project on the human health impacts of Agent Orange.[107] These negotiations broke down in 2005, when neither side could agree on the research protocol and the research project was canceled. More progress has been made on the environmental front. In 2005, the first U.S.-Vietnam workshop on remediation of dioxin was held.[107]

Starting in 2005, the EPA began to work with the Vietnamese government to measure the level of dioxin at the Da Nang Air Base. Also in 2005, the Joint Advisory Committee on Agent Orange, made up of representatives of Vietnamese and U.S. government agencies, was established. The committee has been meeting yearly to explore areas of scientific cooperation, technical assistance and environmental remediation of dioxin.[108]

A breakthrough in the diplomatic stalemate on this issue occurred as a result of United States President George W. Bush's state visit to Vietnam in November 2006. In the joint statement, President Bush and President Triet agreed "further joint efforts to address the environmental contamination near former dioxin storage sites would make a valuable contribution to the continued development of their bilateral relationship."[109] On May 25, 2007, President Bush signed the U.S. Troop Readiness, Veterans' Care, Katrina Recovery, and Iraq Accountability Appropriations Act, 2007 into law for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that included an earmark of $3 million specifically for funding for programs for the remediation of dioxin 'hotspots' on former U.S. military bases, and for public health programs for the surrounding communities;[110] some authors consider this to be completely inadequate, pointing out that the Da Nang Airbase alone will cost $14 million to clean up, and that three others are estimated to require $60 million for cleanup.[43] The appropriation was renewed in the fiscal year 2009 and again in FY 2010. An additional $12 million was appropriated in the fiscal year 2010 in the Supplemental Appropriations Act and a total of $18.5 million appropriated for fiscal year 2011.[111]

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton stated during a visit to Hanoi in October 2010 that the U.S. government would begin work on the clean-up of dioxin contamination at the Da Nang Airbase.[112] In June 2011, a ceremony was held at Da Nang airport to mark the start of U.S.-funded decontamination of dioxin hotspots in Vietnam. Thirty-two million dollars has so far been allocated by the U.S. Congress to fund the program.[113] A $43 million project began in the summer of 2012, as Vietnam and the U.S. forge closer ties to boost trade and counter China's rising influence in the disputed South China Sea.[114]

Vietnamese victims class action lawsuit in U.S. courts

On January 31, 2004, a victim's rights group, the Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange/dioxin (VAVA), filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York in Brooklyn, against several U.S. companies for liability in causing personal injury, by developing, and producing the chemical, and claimed that the use of Agent Orange violated the 1907 Hague Convention on Land Warfare, 1925 Geneva Protocol, and the 1949 Geneva Conventions. Dow Chemical and Monsanto were the two largest producers of Agent Orange for the U.S. military and were named in the suit, along with the dozens of other companies (Diamond Shamrock, Uniroyal, Thompson Chemicals, Hercules, etc.). On March 10, 2005, Judge Jack B. Weinstein of the Eastern District – who had presided over the 1984 U.S. veterans class-action lawsuit – dismissed the lawsuit, ruling there was no legal basis for the plaintiffs' claims. He concluded Agent Orange was not considered a poison under international law at the time of its use by the U.S.; the U.S. was not prohibited from using it as a herbicide; and the companies which produced the substance were not liable for the method of its use by the government.[115] In the dismissal statement issued by Weinstein, he wrote "The prohibition extended only to gases deployed for their asphyxiating or toxic effects on man, not to herbicides designed to affect plants that may have unintended harmful side-effects on people."[116][117]

The Department of Defense's Advanced Research Project Agency's (ARPA) Project AGILE was instrumental in the United States' development of herbicides as a military weapon, an undertaking inspired by the British use of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T to destroy jungle-grown crops and bushes during the insurgency in Malaya. The United States considered British precedent in deciding that the use of defoliants was a legally accepted tactic of war. On November 24, 1961, Secretary of State Dean Rusk advised President John F. Kennedy that herbicide use in Vietnam would be lawful, saying that "[t]he use of defoliant does not violate any rule of international law concerning the conduct of chemical warfare and is an accepted tactic of war. Precedent has been established by the British during the emergency in Malaya in their use of helicopters for destroying crops by chemical spraying."[118][119]

Author and activist George Jackson had written previously that "if the Americans were guilty of war crimes for using Agent Orange in Vietnam, then the British would be also guilty of war crimes as well since they were the first nation to deploy the use of herbicides and defoliants in warfare and used them on a large scale throughout the Malayan Emergency. Not only was there no outcry by other states in response to the United Kingdom's use, but the U.S. viewed it as establishing a precedent for the use of herbicides and defoliants in jungle warfare." The U.S. government was also not a party in the lawsuit because of sovereign immunity, and the court ruled the chemical companies, as contractors of the U.S. government, shared the same immunity. The case was appealed and heard by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in Manhattan on June 18, 2007. Three judges on the court upheld Weinstein's ruling to dismiss the case. They ruled that, though the herbicides contained a dioxin (a known poison), they were not intended to be used as a poison on humans. Therefore, they were not considered a chemical weapon and thus not a violation of international law. A further review of the case by the entire panel of judges of the Court of Appeals also confirmed this decision. The lawyers for the Vietnamese filed a petition to the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case. On March 2, 2009, the Supreme Court denied certiorari and declined to reconsider the ruling of the Court of Appeals.[120][121]

Help for those affected in Vietnam

To assist those who have been affected by Agent Orange/dioxin, the Vietnamese have established "peace villages", which each host between 50 and 100 victims, giving them medical and psychological help. As of 2006, there were 11 such villages, thus granting some social protection to fewer than a thousand victims. U.S. veterans of the war in Vietnam and individuals who are aware and sympathetic to the impacts of Agent Orange have supported these programs in Vietnam. An international group of veterans from the U.S. and its allies during the Vietnam War working with their former enemy—veterans from the Vietnam Veterans Association—established the Vietnam Friendship Village outside of Hanoi.[122]

The center provides medical care, rehabilitation and vocational training for children and veterans from Vietnam who have been affected by Agent Orange. In 1998, The Vietnam Red Cross established the Vietnam Agent Orange Victims Fund to provide direct assistance to families throughout Vietnam that have been affected. In 2003, the Vietnam Association of Victims of Agent Orange (VAVA) was formed. In addition to filing the lawsuit against the chemical companies, VAVA provides medical care, rehabilitation services and financial assistance to those injured by Agent Orange.[123]

The Vietnamese government provides small monthly stipends to more than 200,000 Vietnamese believed affected by the herbicides; this totaled $40.8 million in 2008. The Vietnam Red Cross has raised more than $22 million to assist the ill or disabled, and several U.S. foundations, United Nations agencies, European governments and nongovernmental organizations have given a total of about $23 million for site cleanup, reforestation, health care and other services to those in need.[124]

Vuong Mo of the Vietnam News Agency described one of the centers:[125]

May is 13, but she knows nothing, is unable to talk fluently, nor walk with ease due to for her bandy legs. Her father is dead and she has four elder brothers, all mentally retarded ... The students are all disabled, retarded and of different ages. Teaching them is a hard job. They are of the 3rd grade but many of them find it hard to do the reading. Only a few of them can. Their pronunciation is distorted due to their twisted lips and their memory is quite short. They easily forget what they've learned ... In the Village, it is quite hard to tell the kids' exact ages. Some in their twenties have a physical statures as small as the 7- or 8-years-old. They find it difficult to feed themselves, much less have mental ability or physical capacity for work. No one can hold back the tears when seeing the heads turning round unconsciously, the bandy arms managing to push the spoon of food into the mouths with awful difficulty ... Yet they still keep smiling, singing in their great innocence, at the presence of some visitors, craving for something beautiful.

On June 16, 2010, members of the U.S.-Vietnam Dialogue Group on Agent Orange/Dioxin unveiled a comprehensive 10-year Declaration and Plan of Action to address the toxic legacy of Agent Orange and other herbicides in Vietnam. The Plan of Action was released as an Aspen Institute publication and calls upon the U.S. and Vietnamese governments to join with other governments, foundations, businesses, and nonprofits in a partnership to clean up dioxin "hot spots" in Vietnam and to expand humanitarian services for people with disabilities there.[126][127][128] On September 16, 2010, Senator Patrick Leahy acknowledged the work of the Dialogue Group by releasing a statement on the floor of the United States Senate. The statement urges the U.S. government to take the Plan of Action's recommendations into account in developing a multi-year plan of activities to address the Agent Orange/dioxin legacy.[129]

Use outside of Vietnam

Australia

In 2008, Australian researcher Jean Williams claimed that cancer rates in Innisfail, Queensland, were 10 times higher than the state average because of secret testing of Agent Orange by the Australian military scientists during the Vietnam War. Williams, who had won the Order of Australia medal for her research on the effects of chemicals on U.S. war veterans, based her allegations on Australian government reports found in the Australian War Memorial's archives. A former soldier, Ted Bosworth, backed up the claims, saying that he had been involved in the secret testing. Neither Williams nor Bosworth have produced verifiable evidence to support their claims. The Queensland health department determined that cancer rates in Innisfail were no higher than those in other parts of the state.[130]

Canada

The U.S. military, with the permission of the Canadian government, tested herbicides, including Agent Orange, in the forests near Canadian Forces Base Gagetown in New Brunswick.[131] In 2007, the government of Canada offered a one-time ex gratia payment of $20,000 as compensation for Agent Orange exposure at CFB Gagetown.[132] On July 12, 2005, Merchant Law Group, on behalf of over 1,100 Canadian veterans and civilians who were living in and around CFB Gagetown, filed a lawsuit to pursue class action litigation concerning Agent Orange and Agent Purple with the Federal Court of Canada.[133] On August 4, 2009, the case was rejected by the court, citing lack of evidence.[134] In 2007, the Canadian government announced that a research and fact-finding program initiated in 2005 had found the base was safe.[135]

On February 17, 2011, the Toronto Star revealed that Agent Orange had been employed to clear extensive plots of Crown land in Northern Ontario.[136] The Toronto Star reported that, "records from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s show forestry workers, often students and junior rangers, spent weeks at a time as human markers holding red, helium-filled balloons on fishing lines while low-flying planes sprayed toxic herbicides including an infamous chemical mixture known as Agent Orange on the brush and the boys below."[136] In response to the Toronto Star article, the Ontario provincial government launched a probe into the use of Agent Orange.[137]

Guam

An analysis of chemicals present in the island's soil, together with resolutions passed by Guam's legislature, suggest that Agent Orange was among the herbicides routinely used on and around Andersen Air Force Base and Naval Air Station Agana. Despite the evidence, the Department of Defense continues to deny that Agent Orange was stored or used on Guam. Several Guam veterans have collected evidence to assist in their disability claims for direct exposure to dioxin containing herbicides such as 2,4,5-T which are similar to the illness associations and disability coverage that has become standard for those who were harmed by the same chemical contaminant of Agent Orange used in Vietnam.[138]

Korea

Agent Orange was used in Korea in the late 1960s.[139] In 1999, about 20,000 South Koreans filed two separated lawsuits against U.S. companies, seeking more than $5 billion in damages. After losing a decision in 2002, they filed an appeal.[140] In January 2006, the South Korean Appeals Court ordered Dow Chemical and Monsanto to pay $62 million in compensation to about 6,800 people. The ruling acknowledged that "the defendants failed to ensure safety as the defoliants manufactured by the defendants had higher levels of dioxins than standard", and, quoting the U.S. National Academy of Science report, declared that there was a "causal relationship" between Agent Orange and a range of diseases, including several cancers. The judges failed to acknowledge "the relationship between the chemical and peripheral neuropathy, the disease most widespread among Agent Orange victims".[141]

In 2011, the United States local press KPHO-TV in Phoenix, Arizona, alleged that in 1978 the United States Army had buried 250 drums of Agent Orange in Camp Carroll, the U.S. Army base in Gyeongsangbuk-do, Korea.[142]

Currently, veterans who provide evidence meeting VA requirements for service in Vietnam and who can medically establish that anytime after this 'presumptive exposure' they developed any medical problems on the list of presumptive diseases, may receive compensation from the VA. Certain veterans who served in Korea and are able to prove they were assigned to certain specified around the DMZ during a specific time frame are afforded similar presumption.[143]

New Zealand

The use of Agent Orange has been controversial in New Zealand, because of the exposure of New Zealand troops in Vietnam and because of the production of herbicide used in Agent Orange which has been alleged at various times to have been exported for use in the Vietnam War and to other users by the Ivon Watkins-Dow chemical plant in Paritutu, New Plymouth.[144] There have been continuing claims, as yet unproven, that the suburb of Paritutu has also been polluted.[145] There are cases of New Zealand soldiers developing cancers such as bone cancer, but none has been scientifically connected to exposure to herbicides.[146]

Philippines

Herbicide persistence studies of Agents Orange and White were conducted in the Philippines.[147]

Johnston Atoll

The U.S. Air Force operation to remove Herbicide Orange from Vietnam in 1972 was named Operation Pacer IVY, while the operation to destroy the Agent Orange stored at Johnston Atoll in 1977 was named Operation Pacer HO. Operation Pacer IVY collected Agent Orange in South Vietnam and removed it in 1972 aboard the ship MV Transpacific for storage on Johnston Atoll.[148] The EPA reports that 6,800,000 L (1,800,000 U.S. gal) of Herbicide Orange was stored at Johnston Island in the Pacific and 1,800,000 L (480,000 U.S. gal) at Gulfport, Mississippi.[149]

Research and studies were initiated to find a safe method to destroy the materials, and it was discovered they could be incinerated safely under special conditions of temperature and dwell time.[149] However, these herbicides were expensive, and the Air Force wanted to resell its surplus instead of dumping it at sea.[150] Among many methods tested, a possibility of salvaging the herbicides by reprocessing and filtering out the TCDD contaminant with carbonized (charcoaled) coconut fibers. This concept was then tested in 1976 and a pilot plant constructed at Gulfport.[149]

From July to September 1977 during Operation Pacer HO, the entire stock of Agent Orange from both Herbicide Orange storage sites at Gulfport and Johnston Atoll was subsequently incinerated in four separate burns in the vicinity of Johnston Island aboard the Dutch-owned waste incineration ship MT Vulcanus.[150] As of 2004, some records of the storage and disposition of Agent Orange at Johnston Atoll have been associated with the historical records of Operation Red Hat.[151]

Okinawa, Japan

There have been dozens of reports in the press about use and/or storage of military formulated herbicides on Okinawa that are based upon statements by former U.S. service members that had been stationed on the island, photographs, government records, and unearthed storage barrels. The U.S. Department of Defense has denied these allegations with statements by military officials and spokespersons, as well as a January 2013 report authored by Dr. Alvin Young that was released in April 2013.[148][152]

In particular, the 2013 report rebuts articles written by journalist Jon Mitchell as well as a statement from "An Ecological Assessment of Johnston Atoll" a 2003 publication produced by the United States Army Chemical Materials Agency that states, "in 1972, the U.S. Air Force also brought about 25,000 200L drums of the chemical, Herbicide Orange (HO) to Johnston Island that originated from Vietnam and was stored on Okinawa."[153] The 2013 report states: "The authors of the [2003] report were not DoD employees, nor were they likely familiar with the issues surrounding Herbicide Orange or its actual history of transport to the Island." and detailed the transport phases and routes of Agent Orange from Vietnam to Johnston Atoll, none of which included Okinawa.[148]

Further official confirmation of restricted (dioxin containing) herbicide storage on Okinawa appeared in a 1971 Fort Detrick report titled "Historical, Logistical, Political and Technical Aspects of the Herbicide/Defoliant Program", which mentions that the environmental statement should consider "Herbicide stockpiles elsewhere in PACOM (Pacific Command) U.S. Government restricted materials Thailand and Okinawa (Kadena AFB)."[154] The 2013 DoD report says that the environmental statement urged by the 1971 report was published in 1974 as "The Department of Air Force Final Environmental Statement", and that the latter did not find Agent Orange was held in either Thailand or Okinawa.[148][152]

Thailand

Agent Orange was tested by the United States in Thailand during the Vietnam War. In 1999, buried drums were uncovered and confirmed to be Agent Orange.[156] Workers who uncovered the drums fell ill while upgrading the airport near Hua Hin District, 100 km south of Bangkok.[157] Vietnam-era veterans whose service involved duty on or near the perimeters of military bases in Thailand anytime between February 28, 1961, and May 7, 1975, may have been exposed to herbicides and may qualify for VA benefits.[158] A declassified Department of Defense report written in 1973, suggests that there was a significant use of herbicides on the fenced-in perimeters of military bases in Thailand to remove foliage that provided cover for enemy forces.[158] In 2013, the VA determined that herbicides used on the Thailand base perimeters may have been tactical and procured from Vietnam, or a strong, commercial type resembling tactical herbicides.[158]

United States

The University of Hawaii has acknowledged extensive testing of Agent Orange on behalf of the United States Department of Defense in Hawaii along with mixtures of Agent Orange on Kaua'i Island in 1967–68 and on Hawaii Island in 1966; testing and storage in other U.S. locations has been documented by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs.[159][160]

In 1971, the C-123 aircraft used for spraying Agent Orange were returned to the United States and assigned various East Coast USAF Reserve squadrons, and then employed in traditional airlift missions between 1972 and 1982. In 1994, testing by the Air Force identified some former spray aircraft as "heavily contaminated" with dioxin residue. Inquiries by aircrew veterans in 2011 brought a decision by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs opining that not enough dioxin residue remained to injure these post-Vietnam War veterans. On 26 January 2012, the U.S. Center For Disease Control's Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry challenged this with their finding that former spray aircraft were indeed contaminated and the aircrews exposed to harmful levels of dioxin. In response to veterans' concerns, the VA in February 2014 referred the C-123 issue to the Institute of Medicine for a special study, with results released on January 9, 2015.[161][69]

In 1978, the EPA suspended spraying of Agent Orange in National Forests.[162] Agent Orange was sprayed on thousands of acres of brush in the Tennessee Valley for 15 years before scientists discovered the herbicide was dangerous. Monroe County, Tennessee, is one of the locations known to have been sprayed according to the Tennessee Valley Authority. Forty-four remote acres were doused with Agent Orange along power lines throughout the National Forest.[163]

In 1983, New Jersey declared a Passaic River production site to be a state of emergency. The dioxin pollution in the Passaic River dates back to the Vietnam era, when Diamond Alkali manufactured it in a factory along the river. The tidal river carried dioxin upstream and down, tainting a 17-mile stretch of riverbed in one of New Jersey's most populous areas.[164]

A December 2006 Department of Defense report listed Agent Orange testing, storage, and disposal sites at 32 locations throughout the United States, as well as in Canada, Thailand, Puerto Rico, Korea, and in the Pacific Ocean.[165] The Veteran Administration has also acknowledged that Agent Orange was used domestically by U.S. forces in test sites throughout the United States. Eglin Air Force Base in Florida was one of the primary testing sites throughout the 1960s.[166]

Cleanup programs

In February 2012, Monsanto agreed to settle a case covering dioxin contamination around a plant in Nitro, West Virginia, that had manufactured Agent Orange. Monsanto agreed to pay up to $9 million for cleanup of affected homes, $84 million for medical monitoring of people affected, and the community's legal fees.[167][168]

On 9 August 2012, the United States and Vietnam began a cooperative cleaning up of the toxic chemical on part of Danang International Airport, marking the first time the U.S. government has been involved in cleaning up Agent Orange in Vietnam. Danang was the primary storage site of the chemical. Two other cleanup sites the United States and Vietnam are looking at is Biên Hòa, in the southern province of Đồng Nai—a "hotspot" for dioxin—and Phù Cát airport in the central province of Bình Định, says U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam David Shear. According to the Vietnamese newspaper Nhân Dân, the U.S. government provided $41 million to the project. As of 2017, some 110,000 cubic meters of soil have been "cleaned."[169][170]

The Seabee's Naval Construction Battalion Center at Gulfport, Mississippi was the largest storage site in the United States for agent orange.[171] It was 30 odd acres in size and was still being cleaned up in 2013.[171][172]

In 2016, the EPA laid out its plan for cleaning up an 8-mile stretch of the Passaic River in New Jersey, with an estimated cost of $1.4 billion. The contaminants reached to Newark Bay and other waterways, according to the EPA, which has designated the area a Superfund site.[164] Since destruction of the dioxin requires high temperatures over 1,000 °C, the destruction process is energy intensive.[173]

See also

- Environmental impact of war

- Orange Crush (song)

- Rainbow herbicides

- Scorched earth

- Teratology

- Vietnam Syndrome

Notes

- ↑ Buckingham 1982.

- ↑ "Agent Orange Linked To Skin Cancer Risk". Science 2.0. January 29, 2014. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Agent Orange and Cancer". American Cancer Society. February 11, 2019. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019.

- ↑ "Manufacturing Sites". Agentorangerecord.com. December 28, 2010. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- 1 2 Stocking, Ben (June 14, 2007). "Agent Orange Still Haunts Vietnam, US". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- 1 2 King, Jessica (August 10, 2012). "U.S. in first effort to clean up Agent Orange in Vietnam". CNN. Archived from the original on March 3, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- 1 2 Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2011). "Defoliation". The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War : a Political, Social, and Military History (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-961-0.

- ↑ Raloff, J. (1984). "Agent Orange and Birth Defects Risk". Science News. 126 (8): 117. doi:10.2307/3969152. JSTOR 3969152.

- ↑ corporateName=Department of Veterans' Affairs; address=21 Genge St, Civic/Canberra City. "Agent Orange - Anzac Portal". anzacportal.dva.gov.au. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Vallero, Daniel A. (2007). Biomedical ethics for engineers: ethics and decision making in biomedical and biosystem engineering. Academic Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7506-8227-5. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017.

- 1 2 Furukawa 2004, p. 215.

- ↑ Journal, Claire Perlman for Earth Island (July 14, 2011). "Amazon facing new threat: Agent Orange". the Guardian. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ↑ IOM 1994, p. 90.

- ↑ Young AL, Thalken CE, Arnold EL, Cupello JM, Cockerham LG (1976). Fate of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in the Environment: Summary and Decontamination Recommendations (Technical report). United States Air Force Academy. TR 76 18.

- ↑ "Dioxins". Tox Town. United States National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on March 13, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ↑ Yonemoto, Junzo (2000). "The Effects of Dioxin on Reproduction and Development". Industrial Health. 28 (3): 259–268. doi:10.2486/indhealth.38.259. PMID 10943072.

- 1 2 Ngo et al. 2006.

- ↑ Palmer, Michael (2007). "The Case of Agent Orange". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 29: 172–195. doi:10.1355/cs29-1h.

- ↑ "Facts About Herbicides – Public Health". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Perera, Judith; Thomas, Andy (April 18, 1985). "This horrible natural experiment". New Scientist. pp. 34–36. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ↑ "In Memoriam: Arthur Galston, Plant Biologist, Fought Use of Agent Orange". Yale News. July 18, 2008. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- 1 2 Schneider, Brandon (2003). "Agent Orange: A deadly member of the rainbow". Yale Scientific. 77 (2). Archived from the original on January 25, 2009.

- ↑ Young 2009.

- ↑ Verwey 1977, p. 111.

- ↑ New Scientist, 19 April 1985, p. 34, https://books.google.ca/books?id=q7v_rDK0uOgC&pg=PA34&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false Archived November 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Haberman, Clyde (May 11, 2014). "Agent Orange's Long Legacy, for Vietnam and Veterans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ↑ Hough, Peter (1998). The Global Politics of Pesticides: Forging Consensus from Conflicting Interests. Earthscan. p. 61. ISBN 9781844079872.

- ↑ "Why Hasn't The Government Learned Anything From The Agent Orange Health Crisis?". Task & Purpose. April 13, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ↑ Buckingham 1982, p. 11–12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lewy, Guenter (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 263

- ↑ Pellow 2007, p. 159.

- 1 2 Stellman et al. 2003.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (1997). "Agent Orange". Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO.

- ↑ Huntington, Samuel P. (July 1968). "The Bases of Accommodation". Foreign Affairs. 46 (4): 642–656. doi:10.2307/20039333. JSTOR 20039333.

- ↑ Schuck 1987, p. 16.

- ↑ Young 2009, p. 26.

- ↑ Vietnam War: French court to hear landmark Agent Orange case Archived May 3, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, January 25, 2021

- ↑ Hay 1982, p. 151.

- ↑ Furukawa 2004, p. 143.

- ↑ Stanford Biology Study Group 1971, p. 36.

- ↑ Luong 2003, p. 3.

- ↑ Fawthrop, Tom (June 14, 2004). "Vietnam's war against Agent Orange". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 10, 2019.

- 1 2 Fawthrop, Tom (February 10, 2008). "Agent of Suffering". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 30, 2019.

- ↑ Fuller, Thomas (August 9, 2012). "4 Decades on, U.S. Starts Cleanup of Agent Orange in Vietnam". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- 1 2 Kolko 1994, p. 144–145.

- ↑ Verwey 1977, p. 113.

- ↑ Verwey 1977, p. 111-113.

- ↑ Verwey 1977, p. 116.

- 1 2 3 Turse, Nick (2013). Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 95–99. ISBN 978-0-8050-9547-0. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017.

- ↑ Peterson, Doug (Spring 2005). "Matters of Light: Arthur W. Galston". LASNews Magazine. University of Illinois. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010.

- ↑ Schuck 1987, p. 19.

- ↑ Schlager, Neil (1994). When Technology Fails: Significant Technological Disasters, Accidents, and Failures of the Twentieth Century. Gale Research. p. 104.

- ↑ "United States of America: Practice Relating to Rule 76. Herbicides". Customary IHL Database. International Committee of the Red Cross. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ↑ "What Is Agent Orange? What Types of Cancer Does It Cause?". Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- 1 2 Denselow, Robin (December 3, 1998). "Agent Orange blights Vietnam". BBC News. Archived from the original on January 25, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Professor Nguyen Viet Nhan: Helping Child Victims of Agent Orange Defoliation". Gaia Discovery. December 13, 2010. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ↑ Thornton, Joe (2000). Pandora's Poison: Chlorine, Health, and a New Environmental Strategy. MIT Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-262-70084-9.

- ↑ "Ủng hộ nạn nhân chất độc da cam/Đi-ô-xin" [Support for victims of Agent Orange / Dioxin] (in Vietnamese). Vietnam Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on April 7, 2008.

- ↑ IOM 1994, p. iii.

- 1 2 King, Jesse (November 8, 2012). "Birth Defects Caused by Agent Orange". Embryo Project Encyclopedia. hdl:10776/4202. ISSN 1940-5030. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ↑ Viet Nam – Russia Tropical Centre (June 2009). Evaluation of Contamination at the Agent Orange Dioxin Hot Spots in Bien Hoa, Phu Cat and Vicinity, Vietnam (PDF) (Report). Hanoi, Vietnam: Office of the National Committee 33, Ministry of Natural Resource and Environment. UNDP1391.2. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 25, 2019.

- ↑ Hatfield Consultants; Office of the National Steering Committee 33 (2007). Assessment of dioxin contamination in the environment and human population in the vicinity of Da Nang Airbase, Viet Nam (PDF) (Final Report). Vancouver, Canada: Hatfield Consultants. DANDI1283.4. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 25, 2019.

- ↑ Hermann, Kenneth J. (April 25, 2006). "Killing Me Softly: How Agent Orange Murders Vietnam's Children". Political Affairs. Archived from the original on September 17, 2014.

- ↑ Sidath, Viranga Panangala; Shedd, Daniel (November 18, 2014). Veterans Exposed to Agent Orange: Legislative History, Litigation, and Current Issues (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. R43790. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Veterans Exposed to Agent Orange". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. January 19, 2018. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ Fleischer, Doris Zames; Zames, Freida (2001). The disability rights movement: from charity to confrontation. Temple University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-56639-812-1. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017.

- ↑ Nguyen, Ha (November 19, 2004). "Most Americans favor compensation for Agent Orange victims". Embassy of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in the United States. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (2018). Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam: Update 11. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-47716-1. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- 1 2 Committee to Evaluate the Potential Exposure of Agent Orange/TCDD Residue and Level of Risk of Adverse Health Effects for Aircrew of Post-Vietnam C-123 Aircraft; Board on the Health of Select Populations. Post-Vietnam Dioxin Exposure in Agent Orange-Contaminated C-123 Aircraft. Institute of Medicine (Report). Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Vietnam Era Health Retrospective Observational Study". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- 1 2 "Postservice mortality among Vietnam veterans. The Centers for Disease Control Vietnam Experience Study". JAMA. 257 (6): 790–795. February 13, 1987. doi:10.1001/jama.1987.03390060080028. hdl:2027/ucbk.ark:/28722/h27w6770k. PMID 3027422.

- ↑ "Agent Orange: Diseases Associated with Agent Orange Exposure". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. March 25, 2010. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ↑ Frumkin 2003, p. 257.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jon (April 12, 2011). "Evidence for Agent Orange on Okinawa". Japan Times. p. 12. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011.

- ↑ Chamie, Karim; deVere White, Ralph W.; Lee, Denis; Ok, Joonha; Ellison, Lars M. (October 17, 2008). "Agent Orange exposure, Vietnam War veterans, and the risk of prostate cancer". Cancer. 113 (9): 2464–2470. doi:10.1002/cncr.23695. PMID 18666213. S2CID 7623342.

- ↑ Ansbaugh, Nathan; Shannon, Jackilen; Mori, Motomi; Farris, Paige E.; Garzotto, Mark (July 1, 2013). "Agent Orange as a risk factor for high-grade prostate cancer". Cancer. 119 (13): 2399–2404. doi:10.1002/cncr.27941. PMC 4090241. PMID 23670242.

- ↑ Chang, ET; Boffetta, P; Adami, HO; Cole, P; Mandel, JS (2014). "A critical review of the epidemiology of Agent Orange/TCDD and prostate cancer". Eur J Epidemiol. 29 (10): 667–723. doi:10.1007/s10654-014-9931-2. PMC 4197347. PMID 25064616.

- 1 2 Dunst, Charles (July 20, 2019). "The U.S.'s Toxic Agent Orange Legacy: Washington Has Admitted to the Long-Lasting Effects of Dioxin Use in Vietnam, But Has Largely Sidestepped the Issue in Neighboring Cambodia and Laos". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019.

- ↑ Ana, Phann; Doyle, Kevin (March 20, 2004). "Agent Orange's Legacy". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- ↑ "4 Decades on, U.S. Starts Cleanup of Agent Orange in Vietnam". The New York Times. New York. August 9, 2012. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- ↑ 'Agent Orange: Limited Information Is Available on the Number of Civilians Exposed in Vietnam and Their Workers' Compensation Claims,' Archived February 26, 2021, at the Wayback Machine GAO report number GAO-05-371, April 22, 2005.

- ↑ Chiras, Daniel D. (2010). Environmental science (8th ed.). Jones & Bartlett. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-7637-5925-4.

- ↑ Furukawa 2004, pp. 221–222.

- ↑ Verwey 1977, p. 115.

- ↑ "Convention on the Prohibition of the Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques". Audiovisual Library of International Law. December 10, 1976. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ↑ "Practice Relating to Rule 76. Herbicides". Customary IHL Database. International Committee of the Red Cross. 2013. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ↑ Detter, Ingrid (2013). The Law of War. Ashgate. p. 255. ISBN 9781409464952.

- ↑ Samuel, Richard J., ed. (2005). "Agent Orange". Encyclopedia of United States National Security. SAGE Publications. p. 6. ISBN 9781452265353.

- 1 2 Wilcox 1983.

- ↑ Scott, Wilbur J. (1993). The Politics of Readjustment: Vietnam Veterans Since the War. Transaction Publishers. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-202-30406-9. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Dying Veteran May Speak From Beyond The Grave In Court". Lakeland Ledger. January 25, 1980. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ↑ Croft, Steve (May 7, 1980). "Agent Orange". CBS Evening News. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012.

- ↑ "About the Firm". The Mayerson Law Offices. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ↑ Stanley, Jay; Blair, John D., eds. (1993). Challenges in military health care: perspectives on health status and the provision of care. Transaction Publishers. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-56000-650-3. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017.

- ↑ Harrington, John C. (2005). The challenge to power: money, investing, and democracy. Chelsea Green Publisher. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-931498-97-5.

- ↑ Wilcox, Fred A. (1999). "Toxic Agents". In Chambers, John Whiteclay; Anderson, Fred (eds.). The Oxford companion to American military history. Oxford University Press. p. 725. ISBN 978-0-19-507198-6.

- ↑ Fawthrop, Tom (November 4, 2004). "Agent Orange Victims Sue Monsanto". CorpWatch. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ↑ Prestin, Terry (July 3, 1996). "Agent Orange Panel Closes". The New York Times. Section B; page 1; column 1. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ↑ Kahn, Peter C.; Gochfeld, Michael; Nygren, Martin; et al. (March 18, 1988). "Dioxins and Dibenzofurans in Blood and Adipose Tissue of Agent Orange—Exposed Vietnam Veterans and Matched Controls". JAMA. 259 (11): 1661–7. doi:10.1001/jama.1988.03720110023029. PMID 3343772.

- ↑ Pencak, William (2009). Encyclopedia of the Veteran in America. ABC-CLIO. p. 30. ISBN 9780313087592. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ↑ Office of Public Health and Environmental Hazards (November 11, 2009). "Agent Orange". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on November 1, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ↑ "PL 102-4 and The National Academy of Sciences". The National Academies. November 3, 1981. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Agent Orange Act of 1991". George Washington University. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ↑ Baker, Mike (August 31, 2010). "Aging vets' costs concern Obama's deficit co-chair". Boston.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ↑ Buffler, Patricia A.; Ginevan, Michael E.; Mandel, Jack S.; Watkins, Deborah K. (September 1, 2011). "The Air Force Health Study: An Epidemiologic Retrospective". Annals of Epidemiology. 21 (9): 673–687. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.02.001. ISSN 1047-2797. PMID 21441038.

- ↑ "VA Expands Disability Benefits for Air Force Personnel Exposed to Contaminated C-123 Aircraft" (Press release). United States Department of Veterans Affairs. June 18, 2015. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- 1 2 Young 2009, p. 310.

- ↑ "US, Vietnam to Hold Fourth Joint Advisory Meeting on Agent Orange/Dioxin" (Press release). Embassy of the United States, Hanoi. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Joint Statement Between the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the United States of America" (Press release). United States Department of State. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ↑ Martin 2009, p. 2.

- ↑ Leahy, Patrick. "Statement of Senator Patrick Leahy on the Legacy of Agent Orange" (Press release). Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ↑ DeYoung, Karen (July 22, 2010). "In Hanoi, Clinton highlights closer ties with Vietnam, pushes for human rights". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ↑ "US helps Vietnam to eradicate deadly Agent Orange". BBC News. June 17, 2011. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.