Alveolar cleft grafting

| Alveolar cleft grafting | |

|---|---|

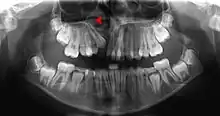

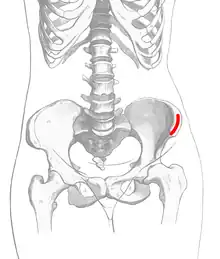

CBCT scan of the maxilla in an 11 year old showing a left alveolar cleft. | |

| Other names | Alveolar grafting, cleft grafting, bone grafting |

| ICD-10-PCS | Q35.1, Q35.9, Q37 |

Alveolar cleft grafting is a surgical procedure, used to repair the defect in the upper jaw that is associated with cleft lip and palate, where the bone defect is filled with bone or bone substitute, and any holes between the mouth and the nose are closed.[1]

An alveolar cleft is a failure of the premaxilla to fuse with the upper jaw leaving a defect in the bone. It is common in people with cleft palate and is also associated with holes between the mouth and the nose that affects speech, and allows fluid to move into the nose when eating and drinking.

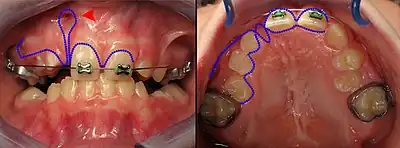

Surgeries on the roof of the mouth early in life typically close the larger hole between the mouth and the nose (caused by the cleft in the palate) but do not repair the defect in the bone, or any holes further forward between the palate and the upper lip. About the age of 8, just before the eye teeth are about to erupt into the bone defect (the cleft), braces are used to first widen the upper jaw, and position the premaxilla. Then, a surgery places bone or a bone substitute in the defect to allow the premaxilla to fuse to the rest of the maxilla, provide bone for eruption of the canine, and close any remaining holes between the mouth and nose. If completed early, the canine teeth will erupt into the mouth with good bone support and remain healthy.

Medical uses

Alveolar cleft grafting is used primarily to allow the eruption of the maxillary canines into the mouth between the ages of 8–13 years old. It is also used to close oranasal fistulas, stop fluid reflux into the nose, improve speech, support the maxillary lateral teeth, and stabilize the jaw for orthodontics or orthognathic surgery.

Technique

In cleft palate patients bone grafting during the mixed dentition has been widely accepted since the mid-1960s. The goals of surgery are to stabilize the maxilla, facilitate the healthy eruption of teeth that are adjacent the cleft, improving the esthetics of the base of the nose, create a bone base for dental implants, and to close any oro-nasal fistulas.[2]

Pre-treatment monitoring and timing

One of the most controversial topics in alveolar cleft grafting is the timing of treatment, however, most centres recommend grafting around the ages of 6–8 years old as the lateral incisor and maxillary canine near the cleft site.[3] This is referred to as secondary grafting during mixed dentition (after eruption of the maxillary central incisors but before the eruption of the canine).[4] A smaller proportion recommend primary grafting around the age of 2, but success rates are lower, and fewer patients are good candidates. Late secondary grafting (after eruption of the canine) has also been advocated but has been largely abandoned due to the loss of tooth support.[4]

In secondary grafting, the dental age of the patient needs to be closely monitored for the eruption of the first maxillary molars in unilateral cases around the age of 6, and in bilateral cases the eruption of central incisors about the age of 8. This timing is used because there is minimal growth of the upper jaw after ages 6–7, the patient is more compliant with orthodontics that is required prior to surgery for expansion, the donor site is better developed, and the grafting precedes the eruption of teeth into the site.[4]

In cases with a single cleft, 35-60% of lateral incisors are congenitally missing,[4] and cannot be relied on for timing. Instead, the eruption of the incisors and first molars is used as a queue to begin assessments. With bilateral cases, the premaxilla must be repositioned before grafting and special consideration must be given. During this time, the orthodontist must be wary of rotating teeth into the cleft site. Last, the size of the patient, defect, and social issues must all be taken into consideration and is best assessed with a CBCT scan as the patient enters the mixed dentition phase of dental development.[5]

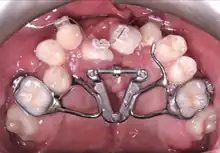

Pre-surgery Orthodontics

In cleft lip and palate cases, the maxilla is typically narrow compared to the lower jaw and must be expanded outward. An expansion appliance is placed in the maxilla 6–9 months prior to correct any crossbite or upper arch constriction.[3] This will widen the cleft size, and so that parents and patients need to be warned the symptoms such as fluid reflux may worsen, although some centres will expand the jaw after surgery is complete. In the case of double clefts, expansion is typically before surgery because the premaxilla needs to be repositioned forward, which cannot occur until the upper jaw is widened to allow room.[4]

Surgical correction

The goals of the surgery are to:[4]

- Close any fistulas between the mouth and the nose

- Leave keratinized tissue around the tooth margins

- Create enough bone to stabilize the maxilla and allow teeth to erupt without a bone defect

At surgery, the gingiva is incised along the cleft margin to allow creation of pocket of tissue up towards the nose (recreating a nasal floor), and down towards the mouth (recreating a palate, and closing the palatal opening). The bony edges of the cleft are cleaned, and any extra teeth in the cleft are removed. The gingiva along the outside part of the upper jaw is raised, so that it can be drawn forward to close the cleft.

After creation of the pocket, but before suturing closed the gingiva a bone graft is placed into the bony defect. This is most commonly harvested from the anterior hip but can also be obtained from other sites, donor bone, or bioactive materials such as bone morphogenic proteins. Once packed the cleft is filled with bone material the gingiva is sutured closed to create a water tight closure between the mouth and the nose. [4]

Source of bone graft

The most common source of the bone graft is from the iliac crest,[6] harvested at the time of the cleft closure. Other sources such as the chin, and posterior iliac crest, or skull can also be used. Artificial grafts such as demineralized bone, recombinent bone morphogenic protein or a mix of harvested bone and artificial grafts have also been used. Insufficient data exists to show that one is beneficial over the other.[1]

Recovery

The mouth wounds recover in 7–10 days with precautions for fluid only diet for 5 days, and not to increase pressure in the nose or sinuses for 2–3 weeks. Evidence that the bone graft is forming will be seen on x-ray at about 8 weeks. Movement of teeth into the graft can begin at 3 months once bone graft consolidation is seen on xray.[4] Recovery from the bone harvest will vary depending on the site (if harvested) with the anterior iliac crest being sore for 2–3 weeks.

Success of the bone graft with the first surgery are approximately 85%[7] but may vary with technique and bone grafting material.[1]

Orthodontics after surgery can close the space between the central incisor and maxillary canine in 50-75% of cases, and for those who can't have the space closed the gap can be filled with a dental implant once growth has finished.[8]

History

The first attempts at bone grafting cleft patients were made by Lexer (1908) and Drachter (1914). Between 1921 and 1952 various attempts were made to graft patients using the turbinate, rib and other harvest sites. Schmid (1954) at meetings in 1951 and 1952 reported on the treatment of patients using iliac crest bone grafts but stated, "The procedure has merely been presented for discussion". By 1964 the iliac crest bone graft had gained popularity and was presented at multiple meetings.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Guo, Jing; Li, Chunjie; Zhang, Qifeng; Wu, Gang; Deacon, Scott A; Chen, Jianwei; Hu, Haikun; Zou, Shujuan; Ye, Qingsong (2011-06-15). Cochrane Oral Health Group (ed.). "Secondary bone grafting for alveolar cleft in children with cleft lip or cleft lip and palate". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD008050. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008050.pub2. PMID 21678372.

- ↑ Lilja, Jan (2009). "Alveolar bone grafting". Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 42 (3): S110-5. doi:10.4103/0970-0358.57200. ISSN 0970-0358. PMC 2825060. PMID 19884665.

- 1 2 Kaura, Arminder S.; Srinivasa, Dhivya R.; Kasten, Steven J. (2018). "Optimal Timing of Alveolar Cleft Bone Grafting for Maxillary Clefts in the Cleft Palate Population". Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 29 (6): 1551–1557. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000004680. ISSN 1049-2275. PMID 29916970. S2CID 49300184.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Peterson's principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery. Miloro, Michael., Peterson, Larry J., 1942- (3rd ed.). Shelton, CT: People's Medical Pub. House-USA. 2012. ISBN 9781607952305. OCLC 813539200.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Stasiak, Marcin; Wojtaszek-Słomińska, Anna; Racka-Pilszak, Bogna (2019). "Current methods for secondary alveolar bone grafting assessment in cleft lip and palate patients — A systematic review". Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 47 (4): 578–585. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2019.01.013. PMID 30733132.

- ↑ Kang, Nak Heon (2017-05-15). "Current Methods for the Treatment of Alveolar Cleft". Archives of Plastic Surgery. 44 (3): 188–193. doi:10.5999/aps.2017.44.3.188. ISSN 2234-6163. PMC 5447527. PMID 28573092.

- ↑ Revington, Peter J; McNamara, Clare; Mukarram, Shumaila; Perera, Esther; Shah, Hemendranath V; Deacon, Scott A (2010). "Alveolar bone grafting: results of a national outcome study". The Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 92 (8): 643–646. doi:10.1308/003588410X12699663904790. ISSN 0035-8843. PMC 3229369. PMID 20615302.

- ↑ Selmanagić, Aida; Nakaš, Enita; Brkić, Hrvoje; Vuković, Amra; Galić, Ivan; Prohić, Samir (2013-12-15). "The Correlation between Third Molar Eruptive Stages and Dental Age in Bosnian and Herzegovinian Children and Adolescents". Acta Stomatologica Croatica. 47 (4): 306–311. doi:10.15644/asc47/4/2. PMC 4872818. PMID 27688373.

- ↑ Bone, Robert C. (1977). "Reconstructive plastic surgery, 2nd Edition, Vol. 5 Edited by John Marquis Converse, 502 pp, illus, W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia". Head & Neck Surgery. 1 (2): 183. doi:10.1002/hed.2890010216. S2CID 10134548.