Aramchol

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Arachidyl amido cholanoic acid; C20-FABAC |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

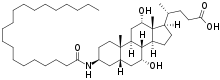

| Formula | C44H79NO5 |

| Molar mass | 702.118 g·mol−1 |

Aramchol is an investigational drug being developed by Galmed Pharmaceuticals as a first-in-class, potentially disease modifying treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH, a more advanced condition of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.[1][2][3][4]

Aramchol, a conjugate of cholic acid and arachidic acid, is a member of a synthetic fatty-acid/bile-acid conjugate (FABAC). FABACs are composed of endogenous compounds, orally administrated with potentially good safety and tolerability parameters.[5]

Aramchol affects liver fat metabolism and has been shown in a Phase IIa clinical study to significantly reduce liver fat content as well as improve metabolic parameters associated with fatty liver disease. Furthermore, it has been shown to be safe for use, and with no severe adverse effects.[6][7]

Aramchol was initially intended to combine a cholesterol solubilizing moiety (a saturated fatty acid) with a bile acid (cholic acid) acting as a vehicle to enable secretion into bile and entry into the enterohepatic circulation to solubilise bile stones.[8] However, early in the development, it was observed that Aramchol reduced liver fat infiltration in animals fed a high fat, lithogenic diet.[9] This effect was confirmed in other animal models and the development plan was modified according to these findings, as fatty liver is an unmet need.

Aramchol has been shown to work by two parallel pathways, leading to synergistic effects:

The SCD1 pathway

Aramchol inhibits the activity of stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase 1 (SCD1) in the liver. This is likely a direct effect since the mRNA of this and other lipogenic genes or the activities of nuclear receptors are not affected. The physiologic effects of SCD1 inhibition are: decreased synthesis of fatty acids, resulting in a decrease in storage triglycerides and other esters of fatty acids. This reduces liver fat (including triglycerides and free fatty acids), and results in an improvement in insulin resistance.[10] Aramchol’s mechanism of action, inhibition of the SCD1 enzyme, has been confirmed in human liver microsomes2 and in animal studies by showing a reduction of the SCD1 activity marker, the fatty acid ratio 16:1/16:0, following Aramchol treatment. These studies showed that the SCD1 inhibition effect of Aramchol is partial (can reach to 70 to 83%). Unlike other SCD1 inhibitors, it was shown that Aramchol’s effects are non-atherogenic.[8] There are at present no known inhibitors of SCD1 with the established safety and efficacy profile of Aramachol.

Reverse cholesterol transport

Aramchol activates cholesterol efflux by stimulating (2 to 4-fold) the ABCA1 transporter, a universal cholesterol export pump present in all cells.[11][12] In animal models, this led to a significant reduction of blood and body cholesterol and an increase in fecal sterol output, mostly neutral sterols.[11]

Aramchol is the first small molecule that was shown to induce ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux without affecting transcriptional control.[11]

References

- ↑ Safadi R, Konikoff FM, Mahamid M, Zelber-Sagi S, Halpern M, Gilat T, Oren R (December 2014). "The fatty acid-bile acid conjugate Aramchol reduces liver fat content in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 12 (12): 2085–91.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.038. PMID 24815326.

- ↑ "Fast Growing Israel Pharma Companies". Jewocity.com. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "AZ strikes Alderley cancer pact, Cerenis mulls IPO, 4D to start microbiome trials in 2015". Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "Aramchol for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease". jwatch.org. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "EndoPAT to be used in trial with potential NASH drug aramchol". Healio.com. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "Galmed Liver Drug Aramchol Gets FDA's Fast-Track Review". RTTNews.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "Update on new treatments for liver diseases". Sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- 1 2 Gilat T, Somjen GJ, Mazur Y, Leikin-Frenkel A, Rosenberg R, Halpern Z, Konikoff F (January 2001). "Fatty acid bile acid conjugates (FABACs)--new molecules for the prevention of cholesterol crystallisation in bile". Gut. 48 (1): 75–9. doi:10.1136/gut.48.1.75. PMC 1728174. PMID 11115826.

- ↑ Gilat T, Leikin-Frenkel A, Goldiner I, Juhel C, Lafont H, Gobbi D, Konikoff FM (August 2003). "Prevention of diet-induced fatty liver in experimental animals by the oral administration of a fatty acid bile acid conjugate (FABAC)". Hepatology. 38 (2): 436–42. doi:10.1053/jhep.2003.50348. PMID 12883488.

- ↑ Leikin-Frenkel A, Goldiner I, Leikin-Gobbi D, Rosenberg R, Bonen H, Litvak A, et al. (December 2008). "Treatment of preestablished diet-induced fatty liver by oral fatty acid-bile acid conjugates in rodents". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 20 (12): 1205–13. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282fc9743. PMID 18989145.

- 1 2 3 Leikin-Frenkel A, Gonen A, Shaish A, Goldiner I, Leikin-Gobbi D, Konikoff FM, et al. (August 2010). "Fatty acid bile acid conjugate inhibits hepatic stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase and is non-atherogenic". Archives of Medical Research. 41 (6): 397–404. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2010.09.001. PMID 21044742.

- ↑ Goldiner I, van der Velde AE, Vandenberghe KE, van Wijland MA, Halpern Z, Gilat T, et al. (June 2006). "ABCA1-dependent but apoA-I-independent cholesterol efflux mediated by fatty acid-bile acid conjugates (FABACs)". The Biochemical Journal. 396 (3): 529–36. doi:10.1042/BJ20051694. PMC 1482810. PMID 16522192.