Asherman's syndrome

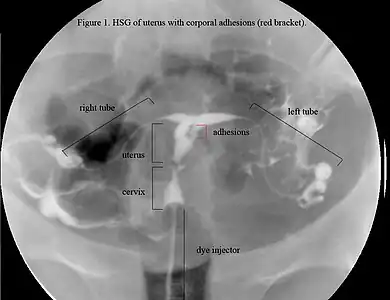

| Asherman syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Intrauterine adhesions (IUA) or Intrauterine synechiae | |

| |

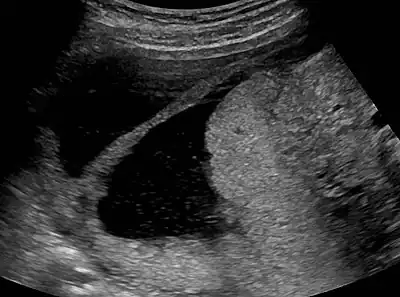

| Ultrasound view. | |

Asherman's syndrome (AS), is an acquired uterine condition that occurs when scar tissue (adhesions) form inside the uterus and/or the cervix.[1] It is characterized by variable scarring inside the uterine cavity, where in many cases the front and back walls of the uterus stick to one another. AS can be the cause of menstrual disturbances, infertility, and placental abnormalities. Although the first case of intrauterine adhesion was published in 1894 by Heinrich Fritsch, it was only after 54 years that a full description of Asherman syndrome was carried out by Joseph Asherman.[2] A number of other terms have been used to describe the condition and related conditions including: uterine/cervical atresia, traumatic uterine atrophy, sclerotic endometrium, and endometrial sclerosis.[3]

There is not any one cause of AS. Risk factors can include myomectomy, cesarean section, infections, age, genital tuberculosis, and obesity. Genetic predisposition to AS is being investigated. There are also studies that show that a severe pelvic infection, independent of surgery may cause AS.[4] AS can develop even if the woman has not had any uterine surgeries, trauma, or pregnancies. While rare in North America and European countries, genital tuberculosis is a cause of Asherman's in other countries such as India.[5]

Signs and symptoms

It is often characterized by a decrease in flow and duration of bleeding (absence of menstrual bleeding, little menstrual bleeding, or infrequent menstrual bleeding)[6] and infertility. Menstrual anomalies are often but not always correlated with severity: adhesions restricted to only the cervix or lower uterus may block menstruation. Pain during menstruation and ovulation is sometimes experienced and can be attributed to blockages. It has been reported that 88% of AS cases occur after a D&C is performed on a recently pregnant uterus, following a missed or incomplete miscarriage, birth, or during an elective termination (abortion) to remove retained products of conception.[7]

Causes

The cavity of the uterus is lined by the endometrium. This lining is composed of two layers, the functional layer (adjacent to the uterine cavity) which is shed during menstruation and an underlying basal layer (adjacent to the myometrium), which is necessary for regenerating the functional layer. Trauma to the basal layer, typically after a dilation and curettage (D&C) performed after a miscarriage, or delivery, or abortion, can lead to the development of intrauterine scars resulting in adhesions that can obliterate the cavity to varying degrees. In the extreme, the whole cavity can be scarred and occluded. Even with relatively few scars, the endometrium may fail to respond to estrogen.

Asherman's syndrome affects women of all races and ages equally, suggesting no underlying genetic predisposition for its development.[8] AS can result from other pelvic surgeries including cesarean sections,[8][9] removal of fibroid tumours (myomectomy) and from other causes such as IUDs, pelvic irradiation, schistosomiasis[10] and genital tuberculosis.[11] Chronic endometritis from genital tuberculosis is a significant cause of severe intrauterine adhesions (IUA) in the developing world, often resulting in total obliteration of the uterine cavity which is difficult to treat.[12]

An artificial form of AS can be surgically induced by endometrial ablation in women with excessive uterine bleeding, in lieu of hysterectomy.

Diagnosis

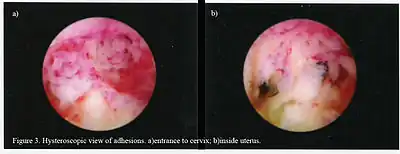

The history of a pregnancy event followed by a D&C leading to secondary amenorrhea or hypomenorrhea is typical. Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis.[13] Imaging by sonohysterography or hysterosalpingography will reveal the extent of the scar formation. Ultrasound is not a reliable method of diagnosing Asherman's Syndrome. Hormone studies show normal levels consistent with reproductive function.

Hysteroscopic view.

Hysteroscopic view.

Classification

Various classification systems were developed to describe Asherman’s syndrome (citations to be added), some taking into account the amount of functioning residual endometrium, menstrual pattern, obstetric history and other factors which are thought to play a role in determining the prognoses. With the advent of techniques which allow visualization of the uterus, classification systems were developed to take into account the location and severity of adhesions inside the uterus. This is useful as mild cases with adhesions restricted to the cervix may present with amenorrhea and infertility, showing that symptoms alone do not necessarily reflect severity. Other patients may have no adhesions but amenorrhea and infertility due to a sclerotic atrophic endometrium. The latter form has the worst prognosis.

Prevention

A 2013 review concluded that there were no studies reporting on the link between intrauterine adhesions and long-term reproductive outcome after miscarriage, while similar pregnancy outcomes were reported subsequent to surgical management (e.g. D&C), medical management or conservative management (that is, watchful waiting).[14] There is an association between surgical intervention in the uterus and the development of intrauterine adhesions, and between intrauterine adhesions and pregnancy outcomes, but there is still no clear evidence of any method of prevention of adverse pregnancy outcomes.[14]

In theory, the recently pregnant uterus is particularly soft under the influence of hormones and hence, easily injured. D&C (including dilation and curettage, dilation and evacuation/suction curettage and manual vacuum aspiration) is a blind, invasive procedure, making it difficult to avoid endometrial trauma. Medical alternatives to D&C for evacuation of retained placenta/products of conception exist including misoprostol and mifepristone. Studies show this less invasive and cheaper method to be an efficacious, safe and an acceptable alternative to surgical management for most women.[15][16] It was suggested as early as in 1993[17] that the incidence of IUA might be lower following medical evacuation (e.g. Misoprostol) of the uterus, thus avoiding any intrauterine instrumentation. So far, one study supports this proposal, showing that women who were treated for missed miscarriage with misoprostol did not develop IUA, while 7.7% of those undergoing D&C did.[18] The advantage of misoprostol is that it can be used for evacuation not only following miscarriage, but also following birth for retained placenta or hemorrhaging.

Alternatively, D&C could be performed under ultrasound guidance rather than as a blind procedure. This would enable the surgeon to end scraping the lining when all retained tissue has been removed, avoiding injury.

Early monitoring during pregnancy to identify miscarriage can prevent the development of, or as the case may be, the recurrence of AS, as the longer the period after fetal death following D&C, the more likely adhesions may be to occur.[17] Therefore, immediate evacuation following fetal death may prevent IUA.The use of hysteroscopic surgery instead of D&C to remove retained products of conception or placenta is another alternative that could theoretically improve future pregnancy outcomes, although it could be less effective if tissue is abundant. Also, hysteroscopy is not a widely or routinely used technique and requires expertise.

There is no data to indicate that suction D&C is less likely than sharp curette to result in Asherman's. A recent article describes three cases of women who developed intrauterine adhesions following manual vacuum aspiration.[19]

Treatment

Fertility may sometimes be restored by removal of adhesions, depending on the severity of the initial trauma and other individual patient factors. Operative hysteroscopy is used for visual inspection of the uterine cavity during adhesion dissection (adhesiolysis). However, hysteroscopy is yet to become a routine gynaecological procedure and only 15% of US gynecologists perform office hysteroscopy.[20] Adhesion dissection can be technically difficult and must be performed with care in order to not create new scars and further exacerbate the condition. In more severe cases, adjunctive measures such as laparoscopy are used in conjunction with hysteroscopy as a protective measure against uterine perforation. Microscissors are usually used to cut adhesions. Electrocauterization is not recommended.[21]

As IUA frequently reform after surgery, techniques have been developed to prevent recurrence of adhesions. Methods to prevent adhesion reformation include the use of mechanical barriers (Foley catheter, saline-filled Cook Medical Balloon Uterine Stent Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, IUCD) and gel barriers (Seprafilm, Spraygel, autocrosslinked hyaluronic acid gel Hyalobarrier) to maintain opposing walls apart during healing,[22][23][24] thereby preventing the reformation of adhesions. Antibiotic prophylaxis is necessary in the presence of mechanical barriers to reduce the risk of possible infections. A common pharmacological method for preventing reformation of adhesions is sequential hormonal therapy with estrogen followed by a progestin to stimulate endometrial growth and prevent opposing walls from fusing together.[25] However, there have been no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing post-surgical adhesion reformation with and without hormonal treatment and the ideal dosing regimen or length of estrogen therapy is not known. The absence of prospective RCTs comparing treatment methods makes it difficult to recommend optimal treatment protocols. Furthermore, diagnostic severity and outcomes are assessed according to different criteria (e.g. menstrual pattern, adhesion reformation rate, conception rate, live birth rate). Clearly, more comparable studies are needed in which reproductive outcome can be analysed systematically.

Follow-up tests (HSG, hysteroscopy or SHG) are necessary to ensure that adhesions have not reformed. Further surgery may be necessary to restore a normal uterine cavity. According to a recent study among 61 patients, the overall rate of adhesion recurrence was 27.9% and in severe cases this was 41.9%.[26] Another study found that postoperative adhesions reoccur in close to 50% of severe AS and in 21.6% of moderate cases.[13] Mild IUA, unlike moderate to severe synechiae, do not appear to reform.

Uterine cavity with uterine scarring

Uterine cavity with uterine scarring Amniotic sheet on ultrasound

Amniotic sheet on ultrasound

Prognosis

The extent of adhesion formation is critical. Mild to moderate adhesions can usually be treated with success. Extensive obliteration of the uterine cavity or fallopian tube openings (ostia) and deep endometrial or myometrial trauma may require several surgical interventions and/or hormone therapy or even be uncorrectable. If the uterine cavity is adhesion free but the ostia remain obliterated, IVF remains an option. If the uterus has been irreparably damaged, surrogacy or adoption may be the only options.

Depending on the degree of severity, AS may result in infertility, repeated miscarriages, pain from trapped blood, and future obstetric complications[13] If left untreated, the obstruction of menstrual flow resulting from adhesions can lead to endometriosis in some cases.[3][27]

Patients who carry a pregnancy even after treatment of IUA may have an increased risk of having abnormal placentation including placenta accreta[28] where the placenta invades the uterus more deeply, leading to complications in placental separation after delivery. Premature delivery,[25] second-trimester pregnancy loss,[29] and uterine rupture[30] are other reported complications. They may also develop incompetent cervix where the cervix can no longer support the growing weight of the fetus, the pressure causes the placenta to rupture and the mother goes into premature labour. Cerclage is a surgical stitch which helps support the cervix if needed.[29]

Pregnancy and live birth rate has been reported to be related to the initial severity of the adhesions with 93, 78, and 57% pregnancies achieved after treatment of mild, moderate and severe adhesions, respectively and resulting in 81, 66, and 32% live birth rates, respectively.[13] The overall pregnancy rate after adhesiolysis was 60% and the live birth rate was 38.9% according to one study.[31]

Age is another factor contributing to fertility outcomes after treatment of AS. For women under 35 years of age treated for severe adhesions, pregnancy rates were 66.6% compared to 23.5% in women older than 35.[28]

Epidemiology

AS has a reported incidence of 25% of D&Cs performed 1–4 weeks post-partum,[27][9][32] up to 30.9% of D&Cs performed for missed miscarriages and 6.4% of D&Cs performed for incomplete miscarriages.[33] In another study, 40% of patients who underwent repeated D&C for retained products of conception after missed miscarriage or retained placenta developed AS.[34]

In the case of missed miscarriages, the time period between fetal demise and curettage may increase the likelihood of adhesion formation due to fibroblastic activity of the remaining tissue.[8][35]

The risk of AS also increases with the number of procedures: one study estimated the risk to be 16% after one D&C and 32% after 3 or more D&Cs.[17] However, a single curettage often underlies the condition.

In an attempts to estimate the prevalence of AS in the general population, it was found in 1.5% of women undergoing hysterosalpingography HSG,[36] and between 5 and 39% of women with recurrent miscarriage.[37][38][39]

After miscarriage, a review estimated the prevalence of AS to be approximately 20% (95% confidence interval: 13% to 28%).[14]

History

The condition was first described in 1894 by Heinrich Fritsch (Fritsch, 1894)[40][41] and further characterized by the Czech-Israeli gynecologist Joseph (Gustav) Asherman (1889–1968)[42] in 1948.[43]

It is also known as Fritsch syndrome, or Fritsch-Asherman syndrome.

References

- ↑ Smikle C, Bhimji SS (2018). "Asherman Syndrome". StatPearls. PMID 28846336. Archived from the original on 2021-01-30. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Conforti A, Alviggi C, Mollo A, De Placido G, Magos A (December 2013). "The management of Asherman syndrome: a review of literature". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 11: 118. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-11-118. PMC 3880005. PMID 24373209.

- 1 2 Palter SF (2005). "High Rates of Endometriosis in Patients With Intrauterine Synechiae (Asherman's Syndrome)". Fertility and Sterility. 86 (Suppl 1): S471. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1239.

- ↑ "Asherman syndrome". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2021-10-07. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

- ↑ Sharma JB, Roy KK, Pushparaj M, Gupta N, Jain SK, Malhotra N, Mittal S (January 2008). "Genital tuberculosis: an important cause of Asherman's syndrome in India". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 277 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1007/s00404-007-0419-0. PMID 17653564. S2CID 23594142.

- ↑ Klein SM, García CR (September 1973). "Asherman's syndrome: a critique and current review". Fertility and Sterility. 24 (9): 722–35. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)39918-6. PMID 4725610.

- ↑ Schorge J, Schaffer J, Halvorson L, Hoffman B, Bradshaw K, Cunningham F (2008). Williams Gynecology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-147257-9.

- 1 2 3 Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ (May 1982). "Intrauterine adhesions: an updated appraisal". Fertility and Sterility. 37 (5): 593–610. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)46268-0. PMID 6281085.

- 1 2 Rochet Y, Dargent D, Bremond A, Priou G, Rudigoz RC (1979). "[The obstetrical future of women who have been operated on for uterine synechiae. 107 cases operated on (author's transl)]" [The obstetrical future of women who have been operated on for uterine synechiae. 107 cases operated on]. Journal de Gynécologie, Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction (in français). 8 (8): 723–6. PMID 553931.

- ↑ Krolikowski A, Janowski K, Larsen JV (May 1995). "Asherman syndrome caused by schistosomiasis". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 85 (5 Pt 2): 898–9. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(94)00371-J. PMID 7724154. S2CID 24103799.

- ↑ Netter AP, Musset R, Lambert A, Salomon Y (February 1956). "Traumatic uterine synechiae: a common cause of menstrual insufficiency, sterility, and abortion". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 71 (2): 368–75. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(16)37600-1. PMID 13283012.

- ↑ Bukulmez O, Yarali H, Gurgan T (August 1999). "Total corporal synechiae due to tuberculosis carry a very poor prognosis following hysteroscopic synechialysis". Human Reproduction. 14 (8): 1960–1. doi:10.1093/humrep/14.8.1960. PMID 10438408.

- 1 2 3 4 Valle RF, Sciarra JJ (June 1988). "Intrauterine adhesions: hysteroscopic diagnosis, classification, treatment, and reproductive outcome". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 158 (6 Pt 1): 1459–70. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(88)90382-1. PMID 3381869.

- 1 2 3 Hooker AB, Lemmers M, Thurkow AL, Heymans MW, Opmeer BC, Brölmann HA, Mol BW, Huirne JA (2013). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of intrauterine adhesions after miscarriage: prevalence, risk factors and long-term reproductive outcome". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (2): 262–78. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt045. PMID 24082042.

- ↑ Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, Creinin MD, Westhoff C, Frederick MM (August 2005). "A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (8): 761–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044064. PMID 16120856.

- ↑ Weeks A, Alia G, Blum J, Winikoff B, Ekwaru P, Durocher J, Mirembe F (September 2005). "A randomized trial of misoprostol compared with manual vacuum aspiration for incomplete abortion". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 106 (3): 540–7. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000173799.82687.dc. PMID 16135584. S2CID 30899930.

- 1 2 3 Friedler S, Margalioth EJ, Kafka I, Yaffe H (March 1993). "Incidence of post-abortion intra-uterine adhesions evaluated by hysteroscopy--a prospective study". Human Reproduction. 8 (3): 442–4. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138068. PMID 8473464.

- ↑ Tam WH, Lau WC, Cheung LP, Yuen PM, Chung TK (May 2002). "Intrauterine adhesions after conservative and surgical management of spontaneous abortion". The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. 9 (2): 182–5. doi:10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60129-6. PMID 11960045.

- ↑ Dalton VK, Saunders NA, Harris LH, Williams JA, Lebovic DI (June 2006). "Intrauterine adhesions after manual vacuum aspiration for early pregnancy failure". Fertility and Sterility. 85 (6): 1823.e1–3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.065. PMID 16674955.

- ↑ Isaacson K (August 2002). "Office hysteroscopy: a valuable but under-utilized technique". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 14 (4): 381–5. doi:10.1097/00001703-200208000-00004. PMID 12151827. S2CID 23079118.

- ↑ Kodaman PH, Arici A (June 2007). "Intra-uterine adhesions and fertility outcome: how to optimize success?". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 19 (3): 207–14. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32814a6473. PMID 17495635. S2CID 3082867.

- ↑ Tsapanos VS, Stathopoulou LP, Papathanassopoulou VS, Tzingounis VA (2002). "The role of Seprafilm bioresorbable membrane in the prevention and therapy of endometrial synechiae". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 63 (1): 10–4. doi:10.1002/jbm.10040. PMID 11787023.

- ↑ Guida M, Acunzo G, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Bifulco G, Piccoli R, Pellicano M, Cerrota G, Cirillo D, Nappi C (June 2004). "Effectiveness of auto-crosslinked hyaluronic acid gel in the prevention of intrauterine adhesions after hysteroscopic surgery: a prospective, randomized, controlled study". Human Reproduction. 19 (6): 1461–4. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh238. PMID 15105384.

- ↑ Abbott J, Thomson A, Vancaillie T (September 2004). "SprayGel following surgery for Asherman's syndrome may improve pregnancy outcome". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 24 (6): 710–1. doi:10.1080/01443610400008206. PMID 16147625. S2CID 13606977.

- 1 2 Roge P, D'Ercole C, Cravello L, Boubli L, Blanc B (April 1996). "Hysteroscopic management of uterine synechiae: a series of 102 observations". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 65 (2): 189–93. doi:10.1016/0301-2115(95)02342-9. PMID 8730623.

- ↑ Yu D, Li TC, Xia E, Huang X, Liu Y, Peng X (March 2008). "Factors affecting reproductive outcome of hysteroscopic adhesiolysis for Asherman's syndrome". Fertility and Sterility. 89 (3): 715–22. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.070. PMID 17681324.

- 1 2 Buttram VC, Turati G (1977). "Uterine synechiae: variations in severity and some conditions which may be conducive to severe adhesions". International Journal of Fertility. 22 (2): 98–103. PMID 20418.

- 1 2 Fernandez H, Al-Najjar F, Chauveaud-Lambling A, Frydman R, Gervaise A (2006). "Fertility after treatment of Asherman's syndrome stage 3 and 4". Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 13 (5): 398–402. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.04.013. PMID 16962521.

- 1 2 Capella-Allouc S, Morsad F, Rongières-Bertrand C, Taylor S, Fernandez H (May 1999). "Hysteroscopic treatment of severe Asherman's syndrome and subsequent fertility". Human Reproduction. 14 (5): 1230–3. doi:10.1093/humrep/14.5.1230. PMID 10325268.

- ↑ Deaton JL, Maier D, Andreoli J (May 1989). "Spontaneous uterine rupture during pregnancy after treatment of Asherman's syndrome". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 160 (5 Pt 1): 1053–4. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(89)90159-2. PMID 2729381.

- ↑ Siegler AM, Valle RF (November 1988). "Therapeutic hysteroscopic procedures". Fertility and Sterility. 50 (5): 685–701. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)60300-X. PMID 3053254.

- ↑ Parent B, Barbot J, Dubuisson JB (1988). "Synéchies utérines" [Management of Uterine synechiae]. Encyclopédie Medico-Chirurgicale, Gynécologie (in français). 140A (Suppl): 10–12.

- ↑ Adoni A, Palti Z, Milwidsky A, Dolberg M (1982). "The incidence of intrauterine adhesions following spontaneous abortion". International Journal of Fertility. 27 (2): 117–8. PMID 6126446.

- ↑ Westendorp IC, Ankum WM, Mol BW, Vonk J (December 1998). "Prevalence of Asherman's syndrome after secondary removal of placental remnants or a repeat curettage for incomplete abortion". Human Reproduction. 13 (12): 3347–50. doi:10.1093/humrep/13.12.3347. PMID 9886512.

- ↑ Fedele L, Bianchi S, Frontino G (December 2006). "Septums and synechiae: approaches to surgical correction". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 49 (4): 767–88. doi:10.1097/01.grf.0000211948.36465.a6. PMID 17082672. S2CID 34164893.

- ↑ Dmowski WP, Greenblatt RB (August 1969). "Asherman's syndrome and risk of placenta accreta". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 34 (2): 288–99. PMID 5816312.

- ↑ Rabau E, David A (November 1963). "Intrauterine Adhesions: Etiology, Prevention, and Treatment". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 22: 626–9. PMID 14082285.

- ↑ Toaff R (1966). "[Some remarks on post-traumatic uterine adhesions]". Revue Française de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. 61 (7): 550–2. PMID 5940506.

- ↑ Ventolini G, Zhang M, Gruber J (December 2004). "Hysteroscopy in the evaluation of patients with recurrent pregnancy loss: a cohort study in a primary care population". Surgical Endoscopy. 18 (12): 1782–4. doi:10.1007/s00464-003-8258-y. PMID 15809790. S2CID 20984257.

- ↑ synd/1521 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Fritsch H (1894). "Ein Fall von volligem Schwaund der Gebormutterhohle nach Auskratzung" [A case of complete disappearance of the uterine cavity after extraction]. Zentralblatt für Gynäkologie (in German). 18: 1337–42.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Adhesions & Asherman's Syndrome". Archived from the original on 2021-11-10. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

- ↑ Asherman JG (December 1950). "Traumatic intra-uterine adhesions". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Empire. 57 (6): 892–6. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1950.tb06053.x. PMID 14804168. S2CID 72393995.

External links

- The secret syndrome leaving women infertile Archived 2021-11-19 at the Wayback Machine Sophie Blake talks about being diagnosed with Asherman's syndrome (Daily Mirror UK)

- The hidden threat to fertility (Times Online) www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/features/article3025016.ece (copy and paste into web browser)

- Overview at iVillage

- How Asherman's syndrome causes infertility or miscarriages Archived 2011-07-08 at the Wayback Machine from Blog: Asherman's Syndrome Watch Archived 2011-07-08 at the Wayback Machine (awareness, education, prevention)

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |