Bidomain model

The bidomain model is a mathematical model to define the electrical activity of the heart. It consists in a continuum (volume-average) approach in which the cardiac mictrostructure is defined in terms of muscle fibers grouped in sheets, creating a complex three-dimensional structure with anisotropical properties. Then, to define the electrical activity, two interpenetrating domains are considered, which are the intracellular and extracellular domains, representing respectively the space inside the cells and the region between them.[1]

The bidomain model was first proposed by Schmitt in 1969[2] before being formulated mathematically in the late 1970s.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

Since it is a continuum model, rather than describing each cell individually, it represents the average properties and behaviour of group of cells organized in complex structure. Thus, the model results to be a complex one and can be seen as a generalization of the cable theory to higher dimensions and, going to define the so-called bidomain equations.[11][12]

Many of the interesting properties of the bidomain model arise from the condition of unequal anisotropy ratios. The electrical conductivity in anisotropic tissues is not unique in all directions, but it is different in parallel and perpendicular direction with respect to the fiber one. Moreover, in tissues with unequal anisotropy ratios, the ratio of conductivities parallel and perpendicular to the fibers are different in the intracellular and extracellular spaces. For instance, in cardiac tissue, the anisotropy ratio in the intracellular space is about 10:1, while in the extracellular space it is about 5:2.[13] Mathematically, unequal anisotropy ratios means that the effect of anisotropy cannot be removed by a change in the distance scale in one direction.[14] Instead, the anisotropy has a more profound influence on the electrical behavior.[15]

Three examples of the impact of unequal anisotropy ratios are

- the distribution of transmembrane potential during unipolar stimulation of a sheet of cardiac tissue,[16]

- the magnetic field produced by an action potential wave front propagating through cardiac tissue,[17]

- the effect of fiber curvature on the transmembrane potential distribution during an electric shock.[18]

Formulation

Bidomain domain

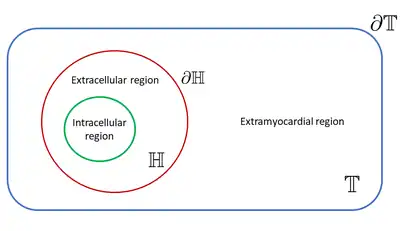

The bidomain domain is principally represented by two main regions: the cardiac cells, called intracellular domain, and the space surrounding them, called extracellular domain. Moreover, usually another region is considered, called extramyocardial region. The intracellular and extracellular domains, which are separate by the cellular membrane, are considered to be a unique physical space representing the heart (), while the extramyocardial domain is a unique physical space adjacent of them (). The extramyocardial region can be considered as a fluid bath, especially when one wants to simulate experimental conditions, or as a human torso to simulate physiological conditions.[12] The boundary of the two principal physical domains defined are important to solve the bidomain model. Here the heart boundary is denoted as while the torso domain boundary is [12]

Unknowns and parameters

The unknowns in the bidomain model are three, the intracellular potential , the extracellular potential and the transmembrane potential , which is defined as the difference of the potential across the cell membrane .[12]

Moreover, some important parameters need to be taken in account, especially the intracellular conductivity tensor matrix , the extracellular conductivity tensor matrix . The transmembrane current flows between the intracellular and extracellular regions and it is in part described by the corresponding ionic current over the membrane per unit area . Moreover, the membrane capacitance per unit area and the surface to volume ratio of the cell membrane need to be considered to derive the bidomain model formulation, which is done in the following section.[12]

Standard formulation

The bidomain model is defined through two partial differential equations (PDE) the first of which is a reaction diffusion equation in terms of the transmembrane potential, while the second one computes the extracellular potential starting from a given transmembran potential distribution.[12]

Thus, the bidomain model can be formulated as follows:

where and can be defined as applied external stimulus currents.[12]

Ionic current equation

The ionic current is usually represented by an ionic model through a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Mathematically, one can write where is called ionic variable. Then, in general, for all , the system reads[19]

Different ionic models have been proposed:[19]

- phenomenological models, which are the simplest ones and used to reproduce macroscopic behavior of the cell.

- physiological models, which take into account both macroscopic behaviour and cell physiology with a quite detailed description of the most important ionic current.

Model of an extramyocardial region

In some cases, an extramyocardial region is considered. This implies the addition to the bidomain model of an equation describing the potential propagation inside the extramyocardial domain.[12]

Usually, this equation is a simple generalized Laplace equation of type[12]

where is the potential in the extramyocardial region and is the corresponding conductivity tensor.

Moreover, an isolated domain assuption is considered, which means that the following boundary conditions are added

being the unit normal directed outside of the extramyocardial domain.[12]

If the extramyocardial region is the human torso, this model gives rise to the forward problem of electrocardiology.[12]

Derivation

The bidomain equations are derived from the Maxwell's equations of the electromagnetism, considering some simplifications.[12]

The first assumption is that the intracellular current can flow only between the intracellular and extracellular regions, while the intracellular and extramyocardial regions can comunicate between them, so that the current can flow into and from the extramyocardial regions but only in the extracellular space.[12]

Using Ohm's law and a quasi-static assumption, the gradient of a scalar potential field can describe an electrical field , which means that[12]

Then, if represent the current density of the electric field , two equations can be obtained[12]

where the subscript and represent the intracellular and extracellular quantities respectively.[12]

The second assumption is that the heart is isolated so that the current that leaves one region need to flow into the other. Then, the current density in each of the intracellular and extracellular domain must be equal in magnitude but opposite in sign, and can be defined as the product of the surface to volume ratio of the cell membrane and the transmembrane ionic current density per unit area, which means that[12]

By combining the previous assumptions, the conservation of current densities is obtained, namely[12]

-

(1)

from which, summing the two equations[12]

This equation states exactly that all currents exiting one domain must enter the other.[12]

From here, it is easy to find the second equation of the bidomain model subtracting from both sides. In fact,[12]

and knowing that the transmembral potential is defined as [12]

Then, knowing the transmembral potential, one can recover the extracellular potential.

Then, the current that flows across the cell membrane can be modelled with the cable equation,[12]

-

(2)

Combining equations (1) and (2) gives[12]

Finally, adding and subtracting on the left and rearranging , one can get the first equation of the bidomain model[12]

which describes the evolution of the transmembrane potential in time.

The final formulation described in the standard formulation section is obtained through a generalization, considering possible external stimulus which can be given through the external applied currents and .[12]

Boundary conditions

In order to solve the model, boundary conditions are needed. The more classical boundary conditions are the following ones, formulated by Tung.[6]

First of all, as state before in the derive section, there ca not been any flow of current between the intracellular and extramyocardial domains. This can be mathematically described as[12]

where is the vector that represents the outwardly unit normal to the myocardial surface of the heart. Since the intracellular potential is not explicitily presented in the bidomain formulation, this condition is usually described in terms of the transmembrane and extracellular potential, knowing that , namely[12]

For the extracellular potential, if the myocardial region is presented, a balance in the flow between the extracellular and the extramyocardial regions is considered[12]

Here the normal vectors from the perspective of both domains are considered, thus the negative sign are necessary. Moreover, a perfect transmission of the potential on the cardiac boundary is necessary, which gives[12]

- .

Instead, if the heart is considered as isoleted, which means that no myocardial region is presented, a possible boundary condition for the extracellular problem is

Reduction to monodomain model

By assuming equal anisotropy ratios for the intra- and extracellular domains, i.e. for some scalar , the model can be reduced to one single equation, called monodomain equation

where the only variable is now the transmembrane potential, and the conductivity tensor is a combination of and [12]

Formulation with boundary conditions in an isolated domain

If the heart is considered as an isolated tissue, which means that no current can flow outside of it, the final formulation with boundary conditions reads[12]

Numerical solution

There are various possible techniques to solve the bidomain equations. Between them, one can find finite difference schemes, finite element schemes and also finite volume schemes. Special considerations can be made for the numerical solution of these equations, due to the high time and space resolution needed for numerical convergence.[20][21]

See also

References

- ↑ Lines, G.T.; Buist, M.L.; Grottum, P.; Pullan, A.J.; Sundnes, J.; Tveito, A. (1 July 2002). "Mathematical models and numerical methods for the forward problem in cardiac electrophysiology". Computing and Visualization in Science. 5 (4): 215–239. doi:10.1007/s00791-003-0101-4. S2CID 123211416.

- ↑ Schmitt, O. H. (1969). Information processing in the nervous system; proceedings of a symposium held at the State University of New York at Buffalo, 21st-24th October, 1968. Springer-Science and Business. pp. 325–331. ISBN 978-3-642-87086-6.

- ↑ Muler AL, Markin VS (1977). "Electrical properties of anisotropic nerve-muscle syncytia-I. Distribution of the electrotonic potential". Biofizika. 22 (2): 307–312. PMID 861269.

- ↑ Muler AL, Markin VS (1977). "Electrical properties of anisotropic nerve-muscle syncytia-II. Spread of flat front of excitation". Biofizika. 22 (3): 518–522. PMID 889914.

- ↑ Muler AL, Markin VS (1977). "Electrical properties of anisotropic nerve-muscle syncytia-III. Steady form of the excitation front". Biofizika. 22 (4): 671–675. PMID 901827.

- 1 2 Tung L (1978). "A bi-domain model for describing ischemic myocardial d-c potentials". PHD Dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, Mass.

- ↑ Miller WT III; Geselowitz DB (1978). "Simulation studies of the electrocardiogram, I. The normal heart". Circulation Research. 43 (2): 301–315. doi:10.1161/01.res.43.2.301. PMID 668061.

- ↑ Peskoff A (1979). "Electric potential in three-dimensional electrically syncytial tissues". Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 41 (2): 163–181. doi:10.1016/s0092-8240(79)80031-2. PMID 760880.

- ↑ Peskoff A (1979). "Electric potential in cylindrical syncytia and muscle fibers". Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 41 (2): 183–192. doi:10.1016/s0092-8240(79)80032-4. PMID 760881.

- ↑ Eisenberg RS, Barcilon V, Mathias RT (1979). "Electrical properties of spherical syncytia". Biophysical Journal. 48 (3): 449–460. Bibcode:1985BpJ....48..449E. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83800-5. PMC 1329358. PMID 4041538.

- ↑ Neu JC, Krassowska W (1993). "Homogenization of syncytial tissues". Critical Reviews in Biomedical Engineering. 21 (2): 137–199. PMID 8243090.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Pullan, Andrew J.; Buist, Martin L.; Cheng, Leo K. (2005). Mathematically modelling the electrical activity of the heart : from cell to body surface and back again. World Scientific. ISBN 978-9812563736.

- ↑ Roth BJ (1997). "Electrical conductivity values used with the bidomain model of cardiac tissue". IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 44 (4): 326–328. doi:10.1109/10.563303. PMID 9125816. S2CID 24225323.

- ↑ Roth BJ (1992). "How the anisotropy of the intracellular and extracellular conductivities influences stimulation of cardiac muscle". Journal of Mathematical Biology. 30 (6): 633–646. doi:10.1007/BF00948895. PMID 1640183. S2CID 257193.

- ↑ Henriquez CS (1993). "Simulating the electrical behavior of cardiac tissue using the bidomain model". Critical Reviews in Biomedical Engineering. 21 (1): 1–77. PMID 8365198.

- ↑ Sepulveda NG, Roth BJ, Wikswo JP (1989). "Current injection into a two-dimensional bidomain". Biophysical Journal. 55 (5): 987–999. Bibcode:1989BpJ....55..987S. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82897-8. PMC 1330535. PMID 2720084.

- ↑ Sepulveda NG, Wikswo JP (1987). "Electric and magnetic fields from two-dimensional bisyncytia". Biophysical Journal. 51 (4): 557–568. Bibcode:1987BpJ....51..557S. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83381-7. PMC 1329928. PMID 3580484.

- ↑ Trayanova N, Roth BJ, Malden LJ (1993). "The response of a spherical heart to a uniform electric field: A bidomain analysis of cardiac stimulation". IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 40 (9): 899–908. doi:10.1109/10.245611. PMID 8288281. S2CID 7593406.

- 1 2 Boulakia, Muriel; Cazeau, Serge; Fernández, Miguel A.; Gerbeau, Jean-Frédéric; Zemzemi, Nejib (24 December 2009). "Mathematical Modeling of Electrocardiograms: A Numerical Study" (PDF). Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 38 (3): 1071–1097. doi:10.1007/s10439-009-9873-0. PMID 20033779. S2CID 10114284.

- ↑ Niederer, S. A.; Kerfoot, E.; Benson, A. P.; Bernabeu, M. O.; Bernus, O.; Bradley, C.; Cherry, E. M.; Clayton, R.; Fenton, F. H.; Garny, A.; Heidenreich, E.; Land, S.; Maleckar, M.; Pathmanathan, P.; Plank, G.; Rodriguez, J. F.; Roy, I.; Sachse, F. B.; Seemann, G.; Skavhaug, O.; Smith, N. P. (3 October 2011). "Verification of cardiac tissue electrophysiology simulators using an N-version benchmark". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 369 (1954): 4331–4351. Bibcode:2011RSPTA.369.4331N. doi:10.1098/rsta.2011.0139. PMC 3263775. PMID 21969679.

- ↑ Pathmanathan, Pras; Bernabeu, Miguel O.; Bordas, Rafel; Cooper, Jonathan; Garny, Alan; Pitt-Francis, Joe M.; Whiteley, Jonathan P.; Gavaghan, David J. (2010). "A numerical guide to the solution of the bidomain equations of cardiac electrophysiology". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 102 (2–3): 136–155. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.05.006. PMID 20553747.