Breast pump

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

A breast pump is a mechanical device that lactating women use to extract milk from their breasts. They may be manual devices powered by hand or foot movements or automatic devices powered by electricity.

History

On June 20, 1854, the United States Patent Office issued Patent No. 11,135 to O.H. Needham for a breast pump.[1][2] Scientific American (1863) credits L.O. Colbin as the inventor and patent applicant of a breast pump.[3] In 1921–23, engineer and chess master Edward Lasker produced a mechanical breast pump that imitated an infant's sucking action and was regarded by physicians as a marked improvement on existing hand-operated breast pumps, which failed to remove all the milk from the breast.[4] The U.S. Patent Office issued U.S. Patent 1,644,257 for Lasker's breast pump.[5] In 1956 Einar Egnell published his groundbreaking work, "Viewpoints on what happens mechanically in the female breast during various methods of milk collection".[6] This article provided insight into the technical aspects of milk extraction from the breast. Many Egnell SMB breast pumps designed through this research are still in operation over 50 years after publication.

Archaeologists working at a glass factory site in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, excavated a 19th-century breast pipe that matches breast pumping instruments in period advertisements.[7]

Reasons for use

Breast pumps are used for many reasons. Many parents use them to continue breastfeeding after they return to work. They express their milk at work, which is later bottle-fed to their child by a caregiver. This use of breast milk is widespread in the United States, where paid family leave is one of the shortest in the developed world. American historian Jill Lepore argues that the need for so-called "lactation rooms" and breast pumps is driven by the corporate desire for parents to return to work immediately rather than mothers' wishes or babies' needs.[8]

A breast pump may also be used to stimulate lactation for women with a low milk supply or those who have not just given birth.

A breast pump may be also used to address a range of challenges parents may encounter breast feeding, including difficulties latching, separation from an infant in intensive care, to feed an infant who cannot extract sufficient milk itself from the breast, to avoid passing medication through breast milk to the baby, or to relieve engorgement, a painful condition whereby the breasts are overfull. Pumping may also be desirable to continue lactation and its associated hormones to aid in recovery from pregnancy even if the pumped milk is not used.[9][10]

In a 2012 policy statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended feeding preterm infants human milk, finding "significant short- and long-term beneficial effects," including lower rates of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). [11] When infants are unable to suckle, mothers can pump if they wish their babies to be fed (via naso-gastric tube) with the mothers' own milk.[12]

Expressing milk for donation is another use for breast pumps. Donor milk may be available from milk banks for babies who are not able to receive their mothers' milk.[13]

Efficiency

The breast pump is not as efficient at removing milk from the breast as most nursing babies or hand expression.[14]

Research done at Stanford University in 2009 showed the correlation of various factors with the volume of milk production in mothers of preterm babies (born before the 31st week of gestation).[15] The research found that hand expression in addition to a breast pump (a technique called "hands-on pumping", or HOP), along with other factors correlated to higher milk production. The study found that mothers who used massage techniques and hand expression more than 5 times a day in the first 3 days after birth increased their milk production 8 weeks later, milk production increased 48%. The authors produced a video showing the technique and states that this technique is good for both mothers of premature infants as well as mothers that return to work or pump for other purposes.[16]

A second article on the same study found that the combination of HOP techniques increased the fat content of the milk expressed.[17]

Mechanical properties

Mechanically, a breast pump triggers the milk ejection response or "letdown". A misconception is that the breast pump suctions milk out of the breast. Pumps achieve letdown by using suction to pull the nipple into the tunnel of the breast shield or flange, then release, which counts as one cycle. Thirty to sixty cycles per minute can be expected with better-quality electric breast pumps. This suction-release cycle can also be accomplished with hand pumps, which the nursing parent operates by compressing a handle.

Multiple sizes of flanges ranging from 13mm to 36mm are available to purchase from various manufacturers. Most pump manufacturers, however, supply their pumps with only standard 24 and 27 mm flanges. What leads to unawareness in pumping women and Lactation consultants about the need to be fit with the right size flange for efficient emptying during pumping.

There are several pump mechanisms. Piston pumps draw a piston through a cylinder to create suction. These tend to operate at low speed, have high reliability, low noise, and long life. Rotary vane pumps use a cam with retractable vanes to create suction and are no longer widely used. Fast-diaphragm pumps use a diaphragm that is acted on by a lever and can operate at thousands of cycles per minute. They tend to be noisy. Slow-diaphragm pumps use a larger diaphragm operated by a cam or lever to generate suction with each stroke. Pumps have also been designed that use venturi effects powered by a faucet or water stream, wall suction in hospitals, or oral suctioning.

Manual breast pumps

Manual breast pumps are operated by squeezing or pulling a handle in a repetitive fashion, allowing the user to directly control the pressure and frequency of milk expression. Though manual pumps are small and inexpensive, they can require significant effort and can be tiring because the user provides all the power. These pumps may not provide sufficient stimulation and emptying of the breast. "Bicycle-horn" style manual pumps can damage breast tissue and harbor bacteria in the rubber suction bulb, which is difficult to clean.[18][19][20]

Foot-powered breast pumps use the same collection tubing and breast horns as electric breast pumps, but are powered by a foot pedal. This eliminates the work of pumping by hand or the need for finding an electrical outlet with privacy.[21]

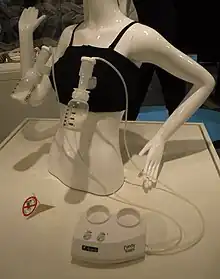

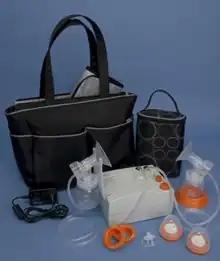

Electric breast pumps

There are two types of electric breast pumps, hospital-grade and personal-use. Hospital-grade pumps are larger and intended for multiple users. Personal-use pumps are generally intended for one user. Electric breast pumps are powered by a motor which supplies suction through plastic tubing to a horn that fits over the nipple. The portions of the pump that come into direct contact with the expressed milk must be sterilized to prevent contamination. This style provides more suction, making pumping significantly faster, and allows users to pump both their breasts at the same time. Electric breast pumps are larger than manual ones, but portable models are available (e.g. in a backpack or shoulder bag). Some models include battery packs or built-in batteries to enable portable operation of the pump. Some electric pumps allow multi-user operation but recommend an accessory kit for each user to maintain cleanliness.[22]

Rental pumps may be recommended when medical conditions temporarily preclude breastfeeding.[22]

Some breast pumps are designed to be part of a "feeding system" so that the milk storage portion of the pump is the baby bottle used to feed the infant. This allows the milk to be collected in the same bottle that will feed the baby eliminating the need to transfer breastmilk. Freezable breastmilk storage bags are available that connect directly to some breast pumps and can then be used with disposable bottle feeding systems.

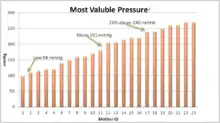

Pressure range and safety

Egnell in 1956 established a 220 mmHg safe maximum for automatic cycling pumps; however, there have been reports of sensitive breasts and nipples at much lower pressures. Hartman et al., in a 2008 study,[23] showed that the maximum comfortable vacuum enhances milk flow and milk yield.

Open collection systems vs. closed collection systems

Pump designs are referred to as either open or closed based on whether there is a barrier between where the tubing connects to the pump and where milk flows into the pump. The plastic tubing and horn of an electric breast pump are commonly referred to as the collection system and typically supply the pump's suction.

A closed collection system has a barrier or diaphragm that separates the pump tubing from the horn. In this design, the suction of the pump motor lifts the diaphragm to create a vacuum within the collection system to extract milk.

In contrast, an open system does not have a barrier between the tubing and the horn. Bacteria and viral filters may be present to prevent contamination or overflow into pump motor. The pump motor's suction is directly passed to the breast versus indirectly as with closed-diaphragm systems.[24]

Open-collection systems can cause milk to overflow into the collection system tubing, and milk particles being drawn into the pump motor. If milk leaks into the pump's tubing, the tubes should be washed, sterilized and air-dried prior to using the pump again. Failure to thoroughly clean collection tubing may lead to mould growth within the tubing. Some models of pumps have bacteria and overflow filters which prevent milk from entering the tubing.[24]

A subtype of the open-collection system is the single-user suction source. These pumps have added hygienic benefit in that all the parts that generate the suction and come in contact with breast milk stay with the mother. The parts that generate the suction are external to the pump and can be removed, preventing cross-contamination. These pumps are considered "hospital grade" and virtually eliminate the chance of cross-contamination of the pump from user to user.[24] However, it is important to clean the diaphragm as condensation or milk reaching this part can cause bacterial contamination.

A disadvantage of the diaphragm is that it may limit the amount of air/suction available to extract milk from the breast. It may also not be able to compensate for larger shield sizes.

There are no studies comparing the open- versus closed-system design. Most information in marketing materials by breast-pump manufacturers is offered without studies to back them up.

Milk collection and storage

Most breast pumps direct the pumped milk into a container that can be used for storage and feeding. Some manufacturers offer adapters to fit a variety of types and sizes of bottles, enabling more flexibility to mix and match products of different brands.

The expressed breast milk (EBM) may be stored and later fed to a baby by bottle. It can either be frozen directly in the bottle, or stored in disposable breast milk bags which are more compact when frozen, thus saving space in a freezer. Expressed milk may be kept at room temperature for up to six hours (at 66-72 degrees Fahrenheit, around 20 degrees Celsius), in an insulated cooler with ice packs for up to one day, refrigerated at the back of the refrigerator for up to 5 days (optimal: use or freeze the milk within 3 days), or frozen for 12 months in a deep freeze separate from a refrigerator maintained at a temperature of 0 degrees Fahrenheit or −18 degrees Celsius (optimal: use this milk within 6 months).[25] If using frozen milk, the oldest milk should be thawed and used first. Thawing can be done by placing the frozen milk in the refrigerator the night before intended use, or by placing the milk in a bowl of warm water. Breast milk should never be microwaved as this can produce dangerous hot areas and may also destroy the milk's antibodies. Many experts recommend discarding thawed milk that isn't used within 24 hours.[25] Breast milk changes to meet a baby's needs so that breast milk expressed when a baby is a newborn won't as completely meet the same baby's needs when he or she is a few months older. Also, storage guidelines might differ for preterm, sick or hospitalized infants.

Expressed milk may be donated to milk banks, which provide human breast milk to premature infants and other children whose mothers cannot provide for them.[26]

See also

- Lactation suppression

- Wet nurse, a woman who feeds a baby who is not her own

References

- ↑ Breast Pump, Patent No. 11,135 Archived 2017-05-02 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-12-14.

- ↑ Breast Pump, Patent No. 11,135 Google Patents abstract

- ↑ Scientific American, Vol. 8, No. 4, January 24, 1863.

- ↑ Edward Lasker, Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters, David McKay, 1951, pp. 249-50. Lasker relates that he designed his device at the urging of pediatrician Dr. I.A. Abt of Chicago, and that Abt and obstetrician Dr. Joseph DeLee considered it a marked improvement on existing hand-operated breast pumps. Dr. DeLee considered the machine indispensable for any hospital that did maternity work. Id.

- ↑ Patent No. 1,644,257 issued by U.S. Patent Office Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 1: Sven Lakartidn. 1956 Oct 5;53(40):2553-64.Links [Viewpoints on what happens mechanically in the female breast during various methods of milk collection.] [Article in Swedish] EGNELL E.

- ↑ White, Rebecca (2013-08-07). "Symbols of motherhood: breast pipe and nursing bottle. Artifact of the month August 2013". Philadelphia Archaeological Forum. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ Lepore, Jill (12 January 2009). "Baby Food: If breast is best, why are women bottling their milk?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ Johns12, Helene M; Forster, Della A; Amir1, Lisa H; McLachlan, Helen L (2013-11-19). "Prevalence and outcomes of breast milk expressing in women with healthy term infants: a systematic review". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 13 (212): 212. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-212. PMC 4225568. PMID 24246046.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Kathleen M.; Geraghty, Sheela R. (August 2011). "The Quiet Revolution: Breastfeeding Transformed With the Use of Breast Pumps". Am J Public Health. 101 (8): 1356–1359. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300136. PMC 3134520. PMID 21680919.

- ↑ American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Breastfeeding (2012). "Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk". Pediatrics. 129 (3): e827–e841. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3552. PMID 22371471. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

Meta-analyses of 4 randomized clinical trials performed over the period 1983 to 2005 support the conclusion that feeding preterm infants human milk is associated with a significant reduction (58%) in the incidence of NEC.

- ↑ "Feeding Your Baby in the NICU". March of Dimes. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ↑ "Milk Donation FAQ". International Breast Milk Project. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Breastfeeding Myths Archived April 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Boob Baby. Accessed on May 16, 2013.

- ↑ J. Morton et al. "Combining hand techniques with electric pumping increases milk production in mothers of preterm infants" J Perinatology (2009) 29 757-764

- ↑ "Home".

- ↑ J Morton et al. "Combining hand techniques with electric pumping increases the caloric content of milk in mothers or preterm infants" J Perinatology (2012) 32 791-796

- ↑ "Breastfeeding and Pumping Accessories". Breastfeeding Made Easier At Home And Work. Womenshealth.gov. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009.

- ↑ "Pumping and milk storage". Breastfeeding. Womenshealth.gov. 1 August 2010. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012.

- ↑ Corley, Heather. "Before You Buy A Breast Pump". About.com. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ A US patent 5304129 A, Suzanne E. Forgach, "Pivotable foot operated breast pump", issued 1994-04-19

- 1 2 "Buying or Renting a Breast Pump". fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Hartman, P, et al. Importance of Vacuum for Milk Expression Breastfeeding Med 3(1) 11-19

- 1 2 3 Shu., Dr. Jennifer (2011-06-13). "Is a used breast pump safe?". CNN. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- 1 2 Mayo Clinic Staff (2020-04-01). "Breast milk storage: Do's and don'ts". mayoclinic.org. The Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- ↑ Henry, Shannon (2007-01-16). "Banking on Milk". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Breast pumps. |

- Collecting and storing breastmilk – California Department of Health Services

- Storing Breast Milk/Thawing Frozen Breast Milk – City of Toronto Health Department

- La Leche League International