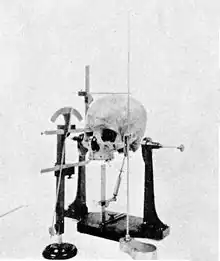

Cephalometry

Cephalometry is the study and measurement of the head, usually the human head, especially by medical imaging such as radiography. Craniometry, the measurement of the cranium (skull), is a large subset of cephalometry. Cephalometry also has a history in phrenology, which is the study of personality and character as well as physiognomy, which is the study of facial features. Cephalometry as applied in a comparative anatomy context informs biological anthropology. In clinical contexts such as dentistry and oral and maxillofacial surgery, cephalometric analysis helps in treatment and research; cephalometric landmarks guide surgeons in planning and operating.

History

The history of cephalometry (cephalo- + -metry, "head measurement") can be traced through art, science, and anthropology. The origins of the important method of measuring has its origins in the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci is perhaps the most well known scientist and artist studying facial proportions during the Renaissance. Da Vinci along with others utilized grids to study the proportions of the face and make generalizations about them. Da Vinci looked for divine proportions in his quest to understand facial proportions. The divine proportion has since been found to exist in 20th centuries of facial proportions as they relate to esthetics. Beginning with Petrus Camper in the 18th century angles began to be employed in the measurement of facial form. Camper also began the practice of ethnographic grouping based on facial form.[1] Anders Retzius defined the cephalic index and classified different shapes of the head. Brachycephalic refers to a small, rounded head. Dolichocephalic refers to a long head. Mesocephalic refers to a medium-sized head, typically between the brachycephalic and dolichocephalic sizes.

Timeline

- Anders Retzius (1796–1860) Defined the cephalic index as means to classify ancient human remains in Europe.

- 1931, orthodontists consecrated the era of cephalometry.

- 1960s began the era of computed cephalometric radiology.

- 1961 Donald and Brown published an article about using ultrasounds for fetal head measurement correlation of diameter and fetal weight.

Applications

Dentistry

Cephalometric analysis is used in dentistry, and especially in orthodontics, to gauge the size and spatial relationships of the teeth, jaws, and cranium. This analysis informs treatment planning, quantifies changes during treatment, and provides data for clinical research. Cephalometry focuses on linear and angular dimensions established by bone, teeth, and facial measurements. It has also been used for measurements of hard and soft tissues of the craniofacial complex.

Obstetrics

Ultrasound cephalometry is useful for determining baby growth in utero. Cephalometry can also determine if an unborn child will pass through the birth canal. Certain 3D imaging applications are now used in obstetric cephalometry. In 1961, Donald and Brown employed ultrasound technique for measurement of the fetal head. Other scientists tried the method and found that the ultrasound technique was 3mm different than the post-natal measurement with calipers. This method requires that the transponder be placed on the maternal abdomen over the area of the fetal head. The transponder is moved until a pair of echos are strong and equal. This indicates that the parietals are perpendicular to the transmitting beam. The distance of the reflections equal the biparietal diameter. From this, the size of the head and the fetal weight can be determined with incredible accuracy. The use of ultrasound cephalometry is meant to be used in addition to other radiographic techniques. Thus far, no ill effects have been reported to the fetus or the mother using the ultrasound fetal cephalometry.[2]

Forensics

Cephalometry can be used to assist in forensic investigations. Researchers work to compile databases of population-level craniometric data. Due to variations in cranial measurements by population these types of databases can help assist investigators working in a known region.

One such database was utilized to test whether craniometric measurements can be utilized to measure stature when only fragmentary remains are available. Researchers created a database cranial measurements utilizing cephalograms of Garo women living in Bangladesh. Head circumference, head length, facial height from 'nasion' to 'gnathion', bizygomatic breadth and stature were all measured and documented. The measurements of the women were placed into a database and then a normative value was given for each measurement within that population. Results indicated that the only head circumference was positively statistically correlated with stature.[3]

One way in which cephalograms can be utilized is for accurate age estimation but not for sex estimation. One study confirmed that the mandibular ramus length is strongly related to chronological age and can be utilized to predict whether an individual is older than 18 years or older with a highly significant degree of accuracy (95% confidence interval). If the ramus length is 7.0 cm or more, then the individual has an 81.25% probability of being 18 years or older. Further, the study confirmed that there is not a strong degree of sexual dimorphism between mandibular ramus length until an individual reaches 16 years of age. The accuracy of predicting sex with mandibular ramus length is only 54% making it an unreliable indicator of sex in forensic contexts. The study also has impacts for providing age estimation of living people. This could be applicable in immigration, criminal and civil investigations, adoption of children, or old-age pension requests. The study utilized scanned cephalometric radiographs to conduct the study.[4] Cephalometry remains to be the most popular and useful method for investigating the craniofacial skeletal morphology. Skull measurements are also important for facial reconstruction in cases of disputed identity. In the Punjab study, the mesocephalic was the most common craniotype followed by dolicocephalic in the tropical regions. The brachycephalic was more common in the temperate regions. Genetic and environmental factors have been suggested for the presence of variations in cephalic indices among population groups. Dietary habits have also been shown to modulate the craniofacial form of people. The data this study gathered is only valid for the adult population and may be useful in future forensic contexts.[5]

Sleep apnea

An Asian study was performed on children ages 3–13 who had obstructive sleep apnea. The study concluded that four cephalometric anthropomorphic parameters were related to the apnea-hypopnea index. Three of which indicated the importance of hyoid position in pediatric sleep apnea. Future studies are needed in this area.[6] A Scottish study used cephalometric radiographs in order to find cause of sleep apnea. This was performed on adult men and women and found that location of the hyoid also correlates with the obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS). The longer the distance of the hyoid to the mandibular plane along with a shorter mandibular corpus showed significantly associated with OSAHS. Compared with a control group, those with OSAHS had the hyoid bone lower in relation to the mandibular plane.[7] By using a cephalometric analysis program, a study was able to conclude that people with a reduced midface length and an inferiorly placed hyoid tend to have smaller airways which can lead to obstructive sleep apnea. Lateral cephalography is useful in analyzing skeletal and soft tissue characteristics. They recorded 22 measurements from the lateral cephalograms and craniometric landmarks were digitized. In other studies, differences in characteristics were noted in the sagittal and vertical planes of apnea sufferers versus the controls. This study did not find these differences between their groups. They did find that using cephalometry there is a difference in craniofacial morphology of persons with obstructive sleep apnea versus the healthy population.[8] On recent open public competitions, machine learning and shape analysis algorithms demonstrated the mean error of 1.92 mm for automated landmarking and up to 93.2% of agreement between automated and manual cephalometry[9][10]

Technology

Advances in technology have allowed scientists and anthropologists to utilize statistical programs in order to estimate ancestry of a skull by taking measurements of various craniometric points. CRANID is a statistical program that is used when the source of a cranium is of unknown origin. Cranial measurements are taken and entered into a worldwide craniometric database that is compared to other known cranial metrics. This information allows the user to be able to estimate ancestry in archaeological, forensic, and repatriation context. It has highest accuracy when sex is able to be determined.[11] Dolphin Imaging Cephalometric and Tracing Software is a cephalometric analysis that can measure airway dimensions and dentofacial parameters. It has been used for studies in obstructive sleep apnea. As cephalometry become more digitized by using different programs and scanners, caution should be taken when interpreting data. Objects measured by computer assisted methods may not be an exact match of the original. Scanning and surface reconstruction can produce some data measurement uncertainty. There have been known cases of different software producing different data even when the same skull is used under the same conditions. Software packages, AMIRA and TIVMI, were used for surface reconstructions. The mean difference between measurements was lower for TIVMI. AMIRA can produce up to 4% error in known measurements and 5% in dry skull measurements. Error rates should be taken into consideration when using digitized software for this purpose.[12]

Other applications of cephalometry

- Study and prediction of facial growth by overlaying older images to compare growth.

- Computer programs have been designed that are capable of utilizing lateral cephalograms and comparing them with growth algorithms to test the reliability of the algorithms. Significant results were found to be valid in utilizing Bolton and Ricketts grown algorithms within 1.5mm. Two-year predictions were the most valid.[13]

- Diagnostics of special pathologies

- Diagnosis of craniofacial anomalies

- Evaluation of nasopharyngeal passage

See also

- Anthropometry

- Cranial vault

- Craniofacial anthropometry

- Phrenology

- Robert M. Ricketts

Bibliography

- Harris, J E, et al. "A field method for the cephalometric x-ray study of skulls in early Nubian cemeteries." American Journal of Physical Anthropology 24, no. 2 (March 1966): 265–273.

- Houlton MC (May 1977). "Divergent biparietal diameter growth rates in twin pregnancies". Obstet Gynecol. 49 (5): 542–5. PMID 850566.

- Littlefield TR, Kelly KM, Cherney JC, Beals SP, Pomatto JK (January 2004). "Development of a new three-dimensional cranial imaging system". J Craniofac Surg. 15 (1): 175–81. doi:10.1097/00001665-200401000-00042. PMID 14704586. S2CID 20288713.

- MW Definition (Archived 2009-10-31)

References

- ↑ Wahl, Norman (2006). "Orthodontics in 3 millennia. Chapter 7: Facial analysis before the advent of the cephalometer". American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 129 (2): 293–298. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.12.011. PMID 16473724.

- ↑ Goldberg; et al. (1966). "Ultrasonic Fetal Cephalometry". Radiology. 87 (2): 328–332. doi:10.1148/87.2.328. PMC 1785849. PMID 5915440.

- ↑ Akhter, Z (2012). "Stature estimation from craniofacial anthropometry in Bangladeshi Garo adult females". Mymensingh Medical Journal.

- ↑ Toledo de Oliveira, Fernando (2014). "Mandibular ramus length as an indicator of chronological age and sex". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 129 (1): 195–201. doi:10.1007/s00414-014-1077-y. PMID 25270589. S2CID 24664868.

- ↑ Khan M; et al. (2015). "A cephalometric study in southern punjab". Professional Medical Journal.

- ↑ Ping-Ying; et al. (2012). "Systematic analysis of cephalometry in obstructive sleep apnea in Asian children". Laryngoscope. 122 (8): 1867–1872. doi:10.1002/lary.23297. PMID 22753016. S2CID 25926760.

- ↑ Riha; et al. (2005). "ACephalometric Comparison of Patients With the Sleep Apnea/Hypopnea Syndrome and Their Siblings". Sleep.

- ↑ Gungor; et al. (2013). "Cephalometric comparison of obstructive sleep apnea patients and healthy controls". European Journal of Dentistry. 7 (1): 48–54. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1698995. PMC 3571509. PMID 23408768.

- ↑ Lindner, Wang (2016). "A benchmark for comparison of dental radiography analysis algorithms". Medical Image Analysis. 31: 63–76. doi:10.1016/j.media.2016.02.004. PMID 26974042.

- ↑ Ibragimov, Wang (2015). "Evaluation and comparison of anatomical landmark detection methods for cephalometric X-Ray images: A grand challenge". IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 34 (9): 1890–1900. doi:10.1109/TMI.2015.2412951. PMID 25794388. S2CID 2886355.

- ↑ Kallenberger, L (November 2012). "Using CRANID to test the population affinity of known crania". Journal of Anatomy. 221 (5): 459–464. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01558.x. PMC 3482354. PMID 22924771.

- ↑ Guyomarc'h, Pierre; et al. (June 2012). "Three-dimensional computer-assisted craniometrics: A comparison of the uncertainty in measurement induced by surface reconstruction performed by two computer programs". Forensic Science International. 219 (1–3): 221–227. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.01.008. PMID 22297143.

- ↑ Sagun, Matthew (2015). "Evaluation of Ricketts' and Bolton's growth prediction algorithms embedded in two diagnostic imaging and cephalometric software". Journal of the World Federation of Orthodontists. 4 (4): 146–150. doi:10.1016/j.ejwf.2015.10.002.